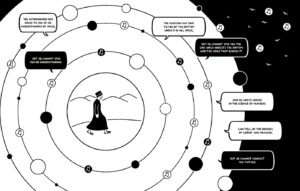

The poems in this new collection register the erasure of Palestinian cultural infrastructure quietly, almost without commentary.

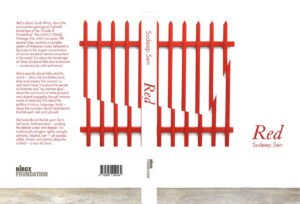

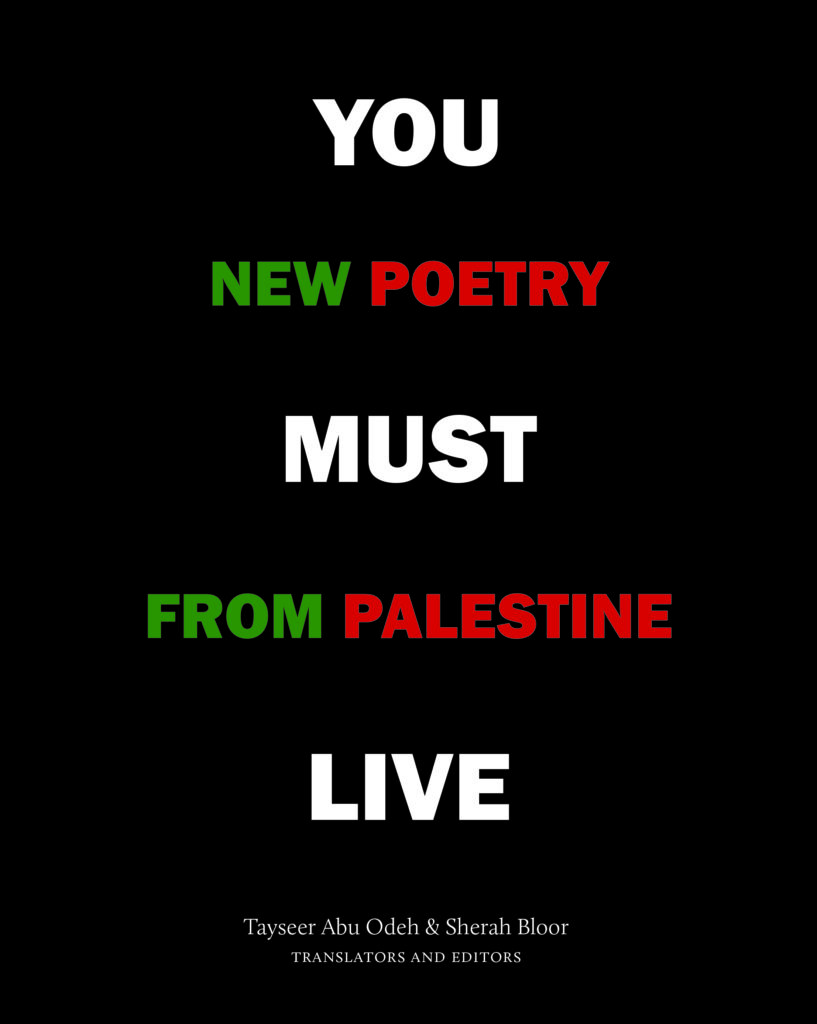

You Must Live: New Poetry from Palestine

Edited and translated by Tayseer Abu Odeh and Sherah Bloor

Copper Canyon Press 2025

ISBN: 9781556597206

Palestinian poetry has long been shaped by catastrophe. Since the Nakba of 1948, which displaced more than 750,000 Palestinians, poets from Ibrahim Tuqan and Fadwa Tuqan to Mahmoud Darwish and Samih al-Qasim have written under occupation, exile, imprisonment and censorship.

To date, many English-language anthologies have necessarily focused on the diaspora — on poems written at a distance from the daily annihilation of space and identity. You Must Live shifts that gravity, because its center is not exile; it is presence. It gives us a glimpse of what it means to write while still inside the ruin and chaos.

Edited and translated by Tayseer Abu Odeh and Sherah Bloor, with a guest editorial presence by Jorie Graham, You Must Live: New Poetry from Palestine is a bilingual anthology of poems by thirty-four poets from Gaza and the West Bank, most of whom were living in Palestine at the time of composition.

Many of these poems were written during the most recent escalation of violence, under conditions in which writing itself — and even the act of replying to an editorial query — could invite lethal consequence. This immediacy is not incidental. It is the book’s ethical and formal core.

As the editors recount in their meticulous, harrowing introduction, these poems did not come from the safety of hindsight. They emerged from the present tense of destruction. They arrived as text messages, screenshots, photographs of handwritten pages, fragments sent through unstable connections. Even the smallest editorial questions — about punctuation, about diction — required poets to climb a pile of rubble or stand exposed in search of a signal.

This immediacy matters because it fundamentally alters how the poems should be read. You Must Live is not poetry “about” war; it is poetry written inside it.

And yet, remarkably, the collection refuses to collapse into raw documentation or rhetorical protest. And in that lies the anthology’s power. What distinguishes the poems gathered here is their refusal to perform suffering for an external audience. Here, devastation does not always arrive through spectacle; it enters through the ordinary. Violence intrudes into errands, conversations, moments of desire, domestic rituals.

In Fida’a Zayed’s “A Song Comes to Mind,” the poet traces the hum of a drone that follows her everywhere, not as event but as accompaniment. It enters the smallest exchanges:

Since morning, the drone hasn’t shut up.

It won’t stop.

Wherever I walk I hear its buzzing.

If I forget, arguing with a vendor over the price of detergent,

it only leaps back quick with my heartbeat.

While I chat with women through windows,

it rebounds, echoing.

The poem does not escalate. It accumulates. When grief finally breaks through, the shift is inward, almost private. Suffering is not staged; it is allowed to occupy the day as it does in life — persistent, uninvited, impossible to mute.

Elsewhere, absence speaks more forcefully than declaration. Yahya Ashour, in “Scale of Catastrophe,” writes of children who once ran freely through Gaza and are now unreachable:

I can’t find them running in the streets.

I can’t find them on Gaza’s beach.

Only here they are still running, inside their photograph.

The last line refuses elaboration. Movement survives only as image. Time collapses into a single, irretrievable frame.

When death is confronted directly, language becomes even more restrained. Waleed al-Aqqad’s elegies refuse metaphorical refuge. In “I Have Never Seen a Corpse Intact,” he describes the burial of a young friend with procedural calm:

We placed your severed hand across your chest,

covered your wounds with flowers,

cried as you wanted.

There is no attempt to redeem the scene through lyric transformation. The poem bears what it must bear — and stops. The restraint here is not aesthetic. It is ethical.

Across the collection, what is destroyed is not only life but continuity. Homes, streets, universities, libraries and publishing houses vanish. The erasure of cultural infrastructure is registered quietly, almost without commentary. The poems do not lament rhetorically; they acknowledge disappearance as fact.

Nasser Rabah’s work makes this lineage explicit, situating Gaza’s poets among others who have written under persecution, without claiming exceptionalism. In “Nothing Kills Me, Nothing,” he writes:

I die slowly, oh Yiannis Ritsos,

Even slower, oh Nazim Hikmet.

From ancient times, the prisoners pass by asking, do you remember?

Then I know who I am.

Empty prison, the dead pass by, waving to me.

I invite them into my museum of memory

Yet nothing kills me, nothing.

I die slowly, oh Federico García Lorca,

Even slower, oh Nasser Rabah.

The gesture is neither ornamental nor consoling. Rather, it places Palestinian suffering within a shared human history of political violence — one that poetry has long been tasked with recording when other forms of testimony fail.

Although this collection belongs to the tradition of poetry of witness, it also revises that tradition through its focus on relationships rather than declaration. These poets write to one another, worry about one another, speak into the possibility that the addressee may already be gone. The book becomes not only a record of loss, but a record of ethical presence — of what it means to remain awake, to remain exact, to remain human when the world insists otherwise.

The translations by Abu Odeh and Bloor are restrained and precise. They resist the urge to heighten anguish or aestheticize pain for an English-speaking audience. The English remains lucid, compressed, and attentive to register.

What stays with me most is the book’s refusal to provide consolation. You Must Live does not offer closure. It does not convert suffering into meaning. It does not reassure the reader that endurance will be rewarded. What it offers instead is something rarer: a sustained practice of attention in conditions designed to annihilate it.

I closed You Must Live aware that reading it was not a neutral act; neither is the writing of this review. These poems do not ask for sympathy. They ask for attention — quiet, sustained, accountable attention. In an era saturated with images and emptied rhetoric on social media and elsewhere, this may be poetry’s most difficult labor. And here, against all material odds, it is carried out with discipline, clarity and restraint.

![Fady Joudah’s <em>[…]</em> Dares Us to Listen to Palestinian Words—and Silences](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/SAMAH-SHIHADI-DAIR-AL-QASSI-charcoal-on-paper-100x60-cm-2023-courtesy-Tabari-Artspace-300x180.jpg)