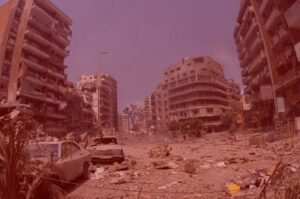

Our senior editor in Beirut relates intimately to the theme of TMR 53, having experienced civil war.

When I was a child, growing up in a Beirut rent asunder by civil war, there was a phrase you heard often about a certain type of person. Sometimes it was a person in the street, wandering about in a daze. Sometimes it was someone shouting from a balcony, reciting in a language slightly off-kilter, both in syntax and rhythm. Sometimes it was a neighbor or distant relative who had suffered a tragedy so monumental, whose grief was so insurmountable, they were spoken to in the patronizing tones reserved for children, and referred to only in whispers.

Majaneen harb, they called them. The war-mad, or rather, the ones rendered mad by war. The word majaneen — plural of majnoun — is derogatory the same way the word crazy is derogatory: because of the haughtiness with which it is administered and the dismissiveness it is meant to convey. I am rational and in control, it says. You are helpless before your own mind. It doesn’t strike me as farfetched to say that behind that haughtiness, just as behind every haughtiness, there is a kind of fear. The fear of the border guard: vigilantly patrolling the boundaries they’ve drawn up, in this case between the rational and the irrational. Still, looking back, I am struck by the fact that it was such a socially-acknowledged fact: war made people mad. War, its attendant instability and grief, was a condition that made people lose their minds.

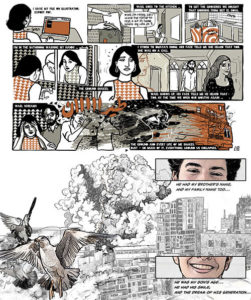

Doubtless many of the people referred to as majaneen harb had pre-existing conditions, mental illnesses that had manifested or become harder to manage under the deprivations of war. But also, many had suffered the kinds of losses that create a parallel universe for the sufferer, one in which the world around them continues to appear as it once was while everything that grounded it in meaning has disappeared. And all of us, in that war, were living various kinds of erasure of meaning, what Joelle Abi Rached, in this issue’s formidable centerpiece essay, “Trauma After Gaza,” clarifies as “the erasure of the conditions (including symbolic ones) necessary for mental health, foreclosing the possibility of psychic well-being entirely.”

The theme for this month’s issue, Out of Our Minds, came out of that sense of psychic unease that so many of us have been feeling and expressing as we try to go about our lives in this moment of profound global crisis. There is an ominous dissonance between what is — burgeoning climate catastrophe, the rising specter of fascism in the West, the collapse of international humanitarian law, devastation and famine in Sudan, and nearly two years of genocide being livestreamed on our phones from Gaza, the world’s leaders continuing to pretend at helplessness while simultaneously shipping weapons off to the murderers — and how we are meant to conduct ourselves — as though all were well: the past laid to rest, the present accounted for and the future assured.

All of our writers this issue are, in one way or another, cataloging dissonance. In so doing, they question, cross, trample, or outright deny that artificial border between the so-called rational and the irrational. Some do this directly, while others take up the question indirectly, through short stories, essays, and a memoir. We have a wide range of pieces from across this region we call the center of the world: from Libya to Pakistan, with Lebanon, Palestine, Egypt, and Iran in between. We also have two essays from Sudan, a crisis that garners an amount of attention not nearly commensurate with the absolutely catastrophic level of death and destruction.

In her essay, “I Don’t Have Time for This Right Now,” Re’al Bakhit writes about the disquieting guilt of living safely in Istanbul while remaining deeply connected to her loved ones in Sudan. “While others faced a real threat of being killed by axes and guns,” she writes, “I was grappling to find comfort from an invisible monster.” She ultimately finds that comfort in her surrounding community, who together continue to celebrate the “hilo” of weddings over Zoom, even as they mourn the “murr” of loved ones killed in the war. Community is also profoundly important in Robert Bociaga’s essay, “Why Wouldn’t We Go Mad,” also about Sudan. He recounts the story of Maab, a woman living in an unknown location abroad, who, armed with only “a cracked smartphone and a Facebook page linked to the Bahri Emergency Room,” takes it entirely upon herself to extend “psychological first aid to survivors still stuck inside Sudan.”

Our literary editor Malu Halasa deals with the same issue — the role of those administering psychological first aid from abroad to people stuck in situations of crisis at home. Regarding the motivation behind her piece, “Remaining in Light, Iranians Search for Solace and Well-Being,” she writes: “I have been thinking about Women Life Freedom protestors in Iran receiving therapy and psychological support from Iranian therapists and doctors thousands of miles away in exile for the last year and a half.” She carried out a series of interviews with Persian psychotherapists as well as brothers Dr. Kamiar and Arash Alaei. “I had been familiar with their story since their arrest in Iran in 2008,” she told me. “Their determination and practical hands-on approach to humanitarian healthcare from HIV drug users in Iran and Yazidi women raped by ISIS in Iraq to Syrian medical students during the war and finally WLF protestors entwined in treatment for both mind and body. Researching, interviewing for, and finally writing the story was important for someone like me who’s produced books on Iran filled with Persian culture and creativity. Those anthologies have been platforms for voices from the country but what about the voices and aspirations of those who have struggled and fallen silent because of the violence against them?”

But one doesn’t have to be a psychologist to be concerned by or involve oneself in another person’s emotional distress. In fact, in Ayça Çubukçu’s fable-like piece, “The Intersection,” which dissolves into poetry at the end, it is the psychologist character warning against involvement, while the protagonist offers a different viewpoint, questioning what it means to care about one another and at the same time preserve our own centers of stability.

Our three short stories in this issue all use point of view to great effect in order to prod at that center of stability in both self and other. In Safa Elnaili’s short story “The Midday Ghoul,” inspired by a Libyan folktale, a mother’s behavior, “like spring in Benghazi, unstable,” is rendered in sinister light through the eyes of her neglected daughter. Kulsum, the main character in Farah Ahamed’s “A Safe Place,” is on the other side of that gaze. Languishing in jail, she is called crazy by those around her for insisting on her innocence. In the story, as often happens in real life, “crazy” is determined by consensus of the majority, even when it is an outright erroneous representation of the circumstances at hand. In Deena Shehata’s “Girl Cat Wolf Under the Bed,” translated from the Arabic by Rana Asfour, the fairytale villain figure of the wolf is recast, by a young girl seeking comfort, as kindred spirit. What is meant to inspire fear becomes the thing that helps defeat it.

Fear is the portal through which the editor of Markaz Bil Arabi, Mohammad Rabie renders a meticulous psychological self-portrait in his essay “All the Old Fears,” translated from the Arabic by me. He painstakingly recounts the cycle it engenders, from which there is no letup or exit, but whose temporal qualities might be subject to change.

There is no letup or exit from the grief of the current moment either. The darkness of Gaza, of watching an ongoing genocide in Gaza, of watching famine ravage Gaza, while also watching the mainstream media downplay or obfuscate or outright deny the ongoing atrocities was foremost in our minds as we put out the call for this issue. There is no letup from the grief — nor should there be. But then how do we look for the light that might guide us toward a future whereby we might exact some measure of justice; the light to illuminate how such a thing might even be possible?

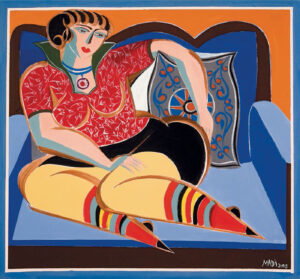

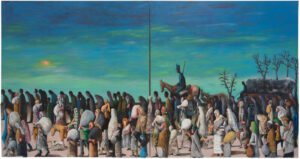

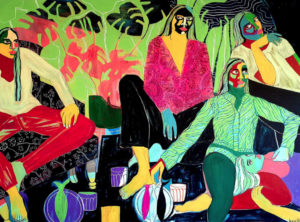

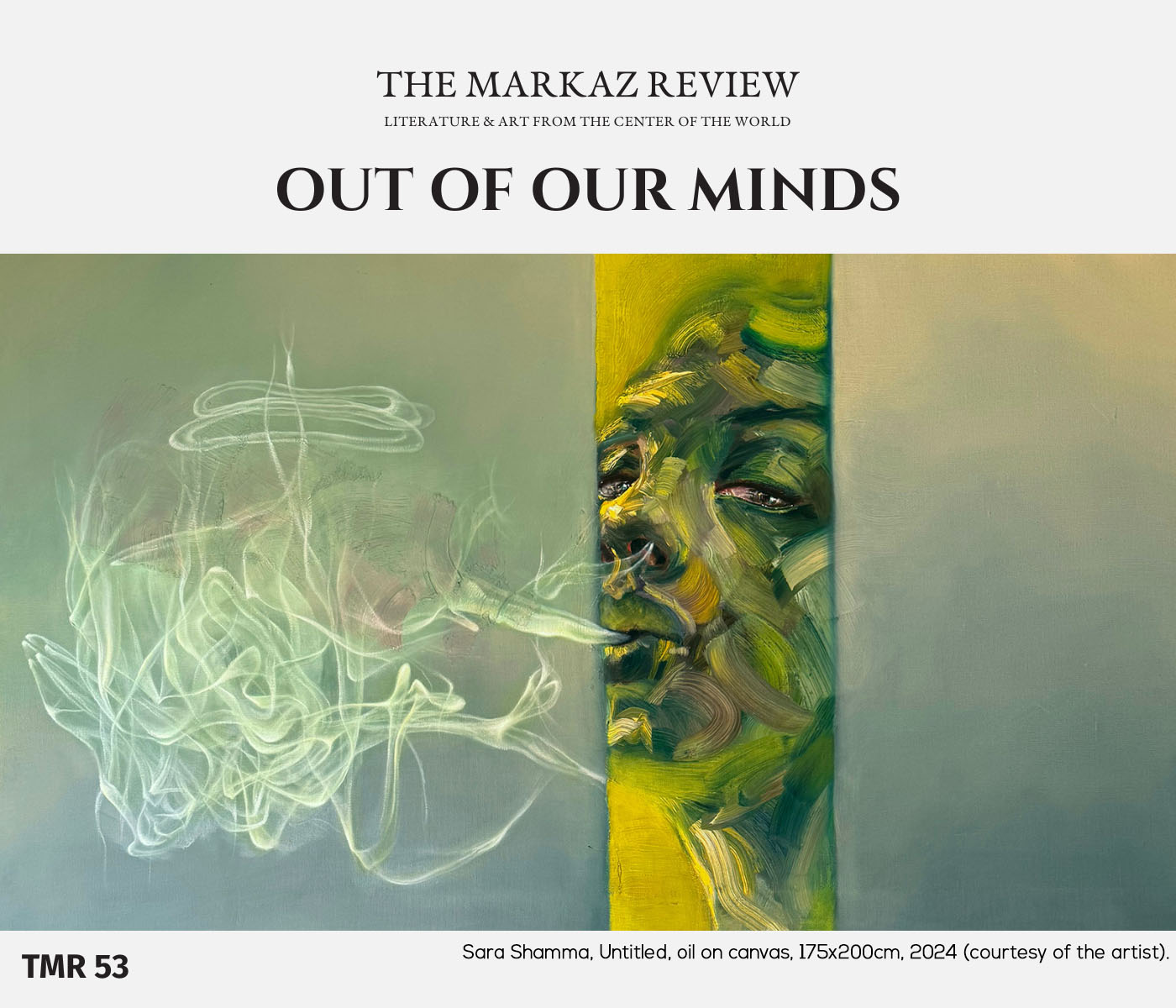

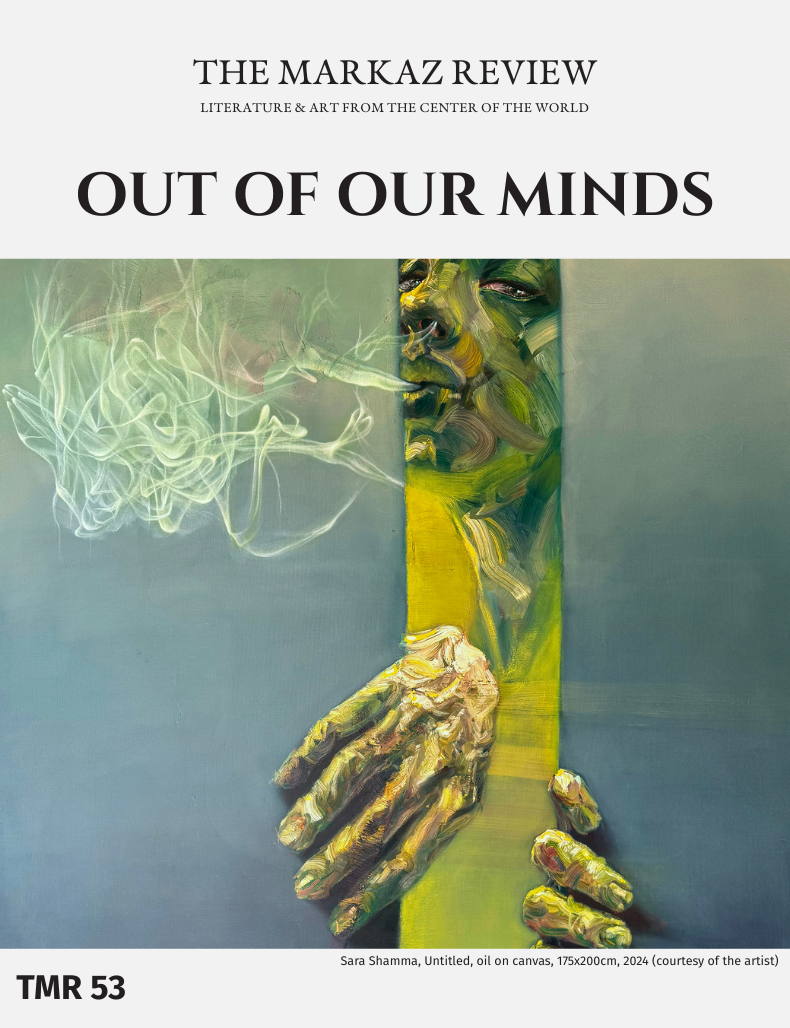

Perhaps the only solution is to look for it directly within the darkness. As Editor-in-Chief Jordan Elgrably discovers in his interview with Syrian artist Sara Shamma, “the grief, the emotion, the madness” of the artist’s work is ultimately “there to remind you of the light.”

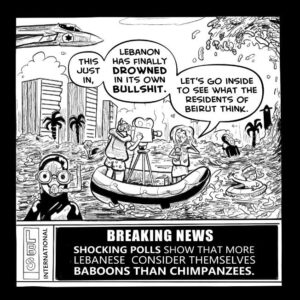

Ultimately, too, even in this issue’s darkest pieces, there is a glimmer of light. In my conversation with Michael Fakhri, a dear friend and the UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food, he insists on avoiding the word “hope,” instead using the word “faith.” In order to arrive at the new world, we must find meaning, he tells me. Back to the idea of meaning, then. But how? How can meaning be found when we are still trying to tear down the illusions that held aloft the old world? Madness might just be the way. For what we call madness, Robert Bociaga calls “intelligence in crisis.” Because “sometimes,” he writes, “to go mad is not to lose yourself — but to stop lying to yourself. To admit the world is unbearable. […] In this way, madness is clarity. A refusal to conform to illusions.”

The idea of “morosophos,” or “wise madness” has been carried over from classical Greek thought into a common literary trope. The mad sage is the one who bucks the conformist illusions of modern society in order to perceive the fundamental truth at the heart of existence. Watching a genocide unfold before our very eyes has given everyone — everyone willing to look, that is — a touch of morosophos. Gaza has made a comforting illusion all but impossible. “Palestine has become a symbol,” writes Joelle Abi Rached, “that exposes the paroxysms of hypocrisy and the language of double standards that defines today the Western liberal order as well as the reductionist vocabulary that pathologizes the other within a moral and spiritual wasteland.”

As you read through this issue, or as the pieces add up, and are read through, against, with, and atop one another, a map begins to emerge of a way out of that spiritual wasteland. It is to embrace, rather than flinch from the grief. Grief is ultimately an opportunity to perform a deep examination of the self and the world; of the self in the world. Thus, one might arrive at the possibility of change as a real choice; a choice earned and made not just despite, but through the experience of grief itself.

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)