Armenian author and University of Alaska professor Seta Kabranian-Melknonian remembers her late husband, freedom fighter Monte Melkonian, and attempts to set the record straight about his exploits on behalf of the blockaded Armenian enclave of Artsakh aka Nagorno Karabakh. This essay is accompanied by three other stories, from Seta Kabranian-Melkonian, Ara Oshagan and Mireille Rebeiz, leading up to the annual remembrance of the Armenian Genocide, on April 24th.

Seta Kabranian-Melkonian

A place I am connected to has been under blockade for months. Though I dislike social media intensely and rarely use it, I search for the latest news on Facebook and Instagram. Little is said about the 120,000 Armenians who suddenly found themselves in a Gaza-style open-air prison. Major media outlets maintain a screaming silence about the issue. Anger, guilt, frustration, despair, and hope form a knot in my chest. I think of the villagers, the many friends of mine living in the region. I slide my right index finger over my cell phone, up and down, right and left. I linger and wait.

“Yeah, Set,” says my friend, her voice void of excitement.

I pause for a second. Asking her the usual how are you? does not make sense.

“Did you get any fruits or vegetables?” I ask.

“The Russian peacekeepers brought us some Apfelsine,” she says. “They delivered apples the next day, but I’m not able to stand in long lines, you know. So, I didn’t get any,” she continues.

“And your heart condition? The surgery?” I ask.

“I don’t know. The surgeon is in Armenia. I can’t decide on that now,” she answers. Her voice lowers an octave. “We don’t know what will happen to us,” she says.

We became friends after we lost our husbands in the same battle some 30 years ago. She had become a single mother with five underage children. I became the family’s godmother. She and many of my old friends live in Artsakh, the Soviet-era Nagorno Karabakh Autonomous Oblast, an Armenian enclave given by Stalin to the Soviet Socialist Republic of Azerbaijan in 1921. After 28 years of relative peace and prosperity, it’s hard to imagine the resurrection of the hardships they went through in the early 1990s, when Armenians and Azerbaijanis fought a war for control of the region. That was a time when blockade, infinite lines for bread and fuel, dark and cold days were part of our everyday vocabulary.

Now, thousands of miles away, on my computer screen is the all-too-familiar yet unfamiliarly barricaded Lachin Corridor, which connects Nagorno Karabakh to Armenia. A road that for a quarter of a century permitted me to be part of a lifeline first bringing a sliver of joy to children of war and then organizing cultural events and humanitarian projects for the survivors. I last traveled through the Lachin corridor in 2018 to be among people with whom I rejoiced in victories and lamented losses. Now the only route to join me with my kin is blockaded. Cut. Slowly amputating the region from its body. I am in denial that I might never again walk on the accustomed streets, light my candles in the usual churches, and spend the night at my friend’s home, as I used to do.

I was a child when I sang “The Lamentation of Karabakh,” after having heard the name for the first time. A Diaspora artist wrote the music for the censored lyrics of Soviet Armenian poet Hovhaness Shiraz.

The one who snatched you from Armenia is not a brother to Armenia

Entangled between us two, you are my child, my Karabakh

After graduating from high school in Lebanon, where I was born and raised, I arrived in Soviet Armenia to study. My new friends there did not know the song. Only a few knew the poem through the author’s recitations. During a college fieldtrip, I stood next to the driver in an overcrowded Soviet LAZ bus. Swaying with the moving tires, through a buzzing microphone I sang:

Karabakh is my mother’s cry, calling me with heartrending faith

Karabakh is my papaver poppy, red yet wearing black on its heart

When I finished the song, my friends clapped and cheered. Our dean shifted in his seat. “Kids, this is not right,” he said.

“Comrade Barseghian, it’s an Armenian patriotic song,” I said with the confidence my foreign student status granted me.

Throughout my college years in Soviet Armenia, I never visited Nagorno Karabakh. However, in the Glasnost and Perestroika phase of my last year at university, it appeared at the forefront of our lives. In February 1988, the Council of People’s Deputies of Nagorno Karabakh Autonomous Oblast voted for reunification with Mother Armenia. The Armenian majority in the enclave had begun massive demonstrations. A few days later, from my dormitory in the center of Armenia’s capital Yerevan, I walked to the Opera Square, where thousands of Armenians gathered in solidarity with the demands. Within days, I was standing among tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands, over a million compatriots to support the Karabakh Movement. Holding a small notebook in my palm, I scribbled a log for my secret fiancé, Monte Melkonian, at the time a political prisoner in France.

By the end of February, owing to their compatriots’ demands for self-determination, Armenians in the Azerbaijani cities of Sumgait and Kirovabad fell victim to pogroms and expulsions. On the other side, Azeris began fleeing Armenia, with some driven out by Armenian paramilitary groups in retaliation for the aforementioned pogroms. We continued our demonstrations in Armenia, hoping for a peaceful resolution that never came. Practicing their right to self-determination in accordance with Soviet law, the Nagorno Karabakh Autonomous Oblast and the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic passed a resolution calling for unification. A pogrom in Baku followed, in which the Armenians were either killed or expelled from their homes. More Azeris then fled or were expelled from Armenia. By the time the Soviet Union collapsed, a full-fledged war had begun between Armenia-supported Nagorno Karabakh and Azerbaijan.

I had already graduated from university and moved to Europe when this happened. After two years of absence, in the autumn of 1990, I was back in Armenia with my fiancé. Following our wedding in the 4th century monastery of Geghard, a friend shouted, “We want a song from the bride! A song from the bride!”

I looked at Monte. During our happiest of times, we both recognized the importance of the “Lamentation of Karabakh.” Monte hugged me around my waist as I sang:

A hive giving its honey to a foreign bee, you are my child, my Karabakh.

A few weeks after our vows, Monte joined the fight for Nagorno Karabakh, the Armenian Artsakh of ancient times. Since his early twenties, he had been determined to help reinstate the rights of his people to live in their ancestral lands. In the process, he was associated with both the heroes and the villains of the time. He was also the first to publicly denounce the villains and distance himself from them. Monte stood for all the oppressed and believed in The Right to Struggle — which is the title of a book of his essays, published in 1993.

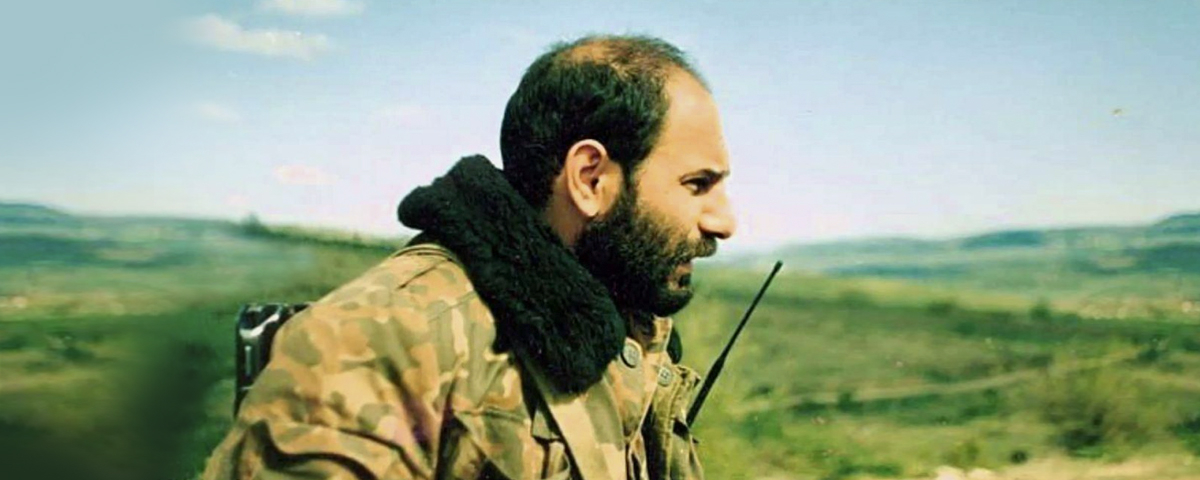

Trained in a Palestinian military camp and already a veteran of the then-ongoing Lebanese Civil War, during which he had helped to defend Beirut’s Armenian quarter against Christian militias, Monte joined in the fierce fighting against the Israeli army when it invaded Lebanon in 1982. He cherished his comrades — Turkish, Kurdish, Corsican, and Basque, all warriors of oppressed nations — fighting for their people’s rights. In the most improbable of situations, like war, he stood for the rights of humans, animals, and the environment alike. He denounced tyrants, including his own, and remained incorruptible to the end. His last battle was in Artsakh, in 1993.

The helicopter hovered, blades chopping the dry heat. Dust clouds took tornado shapes. Military vehicles approached, dragging dirt behind them like a bride’s veil. In a video clip, I am a slender figure in black, hair shining like the center of the native red poppy, as I climb down the steps. Surrounded by my comrades in military fatigues, I watch the men hug each other in grief. I remember feeling their discomfort, confusion, and hesitation. They didn’t dare approach me. They had failed to protect my husband, their commander.

Standing near that helicopter, I gazed at the black-and-white photo pinned to the lapels of the comrades’ fatigues. I had never seen the photo before. Brows furrowed, his dark eyes stare at me. A receding hairline accentuates his forehead, his face framed by the heart-shaped beard. I imagined that, despite the constant hurry and the rumpled tee-shirt he’s wearing in the photo, Monte might have been relaxed. Beyond tears, I took a deep breath. There were no tears.

After his departure on that hot June day, it didn’t take long for folklore to take hold. Infinite versions of Monte flooded the print media with fabricated stories. For one, “he was a holy fighter,” a crusader of sorts; for another, a vengeful warrior (in truth, he considered revenge among the vilest of dispositions). One made him a smoker (he never once tried smoking); another spun him as a singer (to his great disappointment, he was practically tone deaf). Later, many distortions appeared on the internet, on Facebook, Instagram, and other social media platforms.

I boycotted Facebook from the very beginning. But Facebook got in society’s face. Considered an assault by some, it was labeled a marketing success. Soon my emails were infested with “shared” untruths. Literally thousands of them. Imaginary stories, self-aggrandizing, invented affiliations, tall tales of heroism and patriotism, and distorted depictions of a humanist who said people should be judged by their ideas, principles, deeds, and lifestyle, not by their origins. In an October 1988 letter to me, Monte wrote,

Racism is wrong in any part of the world and for any reason. It is totally irrational and illogical. It is a kind of a complex which implies certain insufficiencies on the part of those who believe in it. Our people have been repeatedly subjected to the very anti-human policies of various Turkish governments which have frequently been popularly supported by the mass of the (very un-politicized) Turkish people. Today is no exception. However, this does not at all mean we should be racists or hate all Turks and anything that is Turkish. No, instead we should be calm and objective. We should take a more critical look at our own history to better understand the inter-relationships of our people with our neighbors.

I stare at the two screens on my desk. My computer and my phone repeat the same thing. The words I understand one by one, but strung together they seem undecipherable.

“The people of Nagorno Karabakh are citizens of Azerbaijan,” says the leader of the latter country.

The people of Artsakh have not seen a flesh-and-bone Azeri for the past 30 years. The people of Artsakh have not heard the Azeri language, listened to Azeri music, or eaten Azeri food since the early 1990s. And though the absurdity of the Azerbaijani leader’s statement is staggering, it remains largely unnoticed by the world.

The Azerbaijani government’s public relations machine has been relentless in rewriting history. From maps to history books to demolitions of UNESCO (un)protected ancient sites, the equivalent of millions of dollars must have been spent on deliberate erasure of the Armenian indigenous presence.

This practice extends to social media outlets. Facebook is a great tool in the hands of the Azerbaijani PR machine. Facebook whistleblower Sophie Zhang disclosed that she “saw the most ongoing harm” by Azerbaijan’s ruling political party’s abuse of Facebook to mislead its own citizen to crush the opposition and organize attacks on the Armenian population in Artsakh. The corruption of the Azerbaijani government is well-documented, as is the brutality of its soldiers and their war crimes. Yet the leader of Azerbaijan claims that “the life of Armenians in Karabakh will be much better than during the occupation.”

Against my better judgement, I succumb to the pressure of Monte’s fans, and land on Instagram. My aim is to provide accurate information to rebuild the true image of the warrior. No extra love or hate, simply the truth as I know it, backed up by the privilege of documentation that I possess.

My posts are photos, brief explanations, documented events, and direct quotes. I depict the character of “The Armenian Che Guevara,” as one Western journalist had called him. I underscore ideals that he held dear: fight for the oppressed, as he fought for the Palestinian people in Lebanon; solidarity with all people’s movements, as he showed solidarity with the Kurdish and Turkish progressive freedom fighters; protection of all innocent lives, just as he showed mercy to all in Artsakh. I recall his strict discipline and instruction to his soldiers to save innocent lives, no matter whose it was.

My Instagram is vibrant. Along with support messages, I get a few hate notes, alleging terrorism, murder, and cruelty. Facts have lost credibility. Social media has no place for truth. Its new reality has taken over. Stories of warriors — a rare breed — are not part of it. I think of Malcom X. Society’s resistance to uncomfortable truths saddens me.

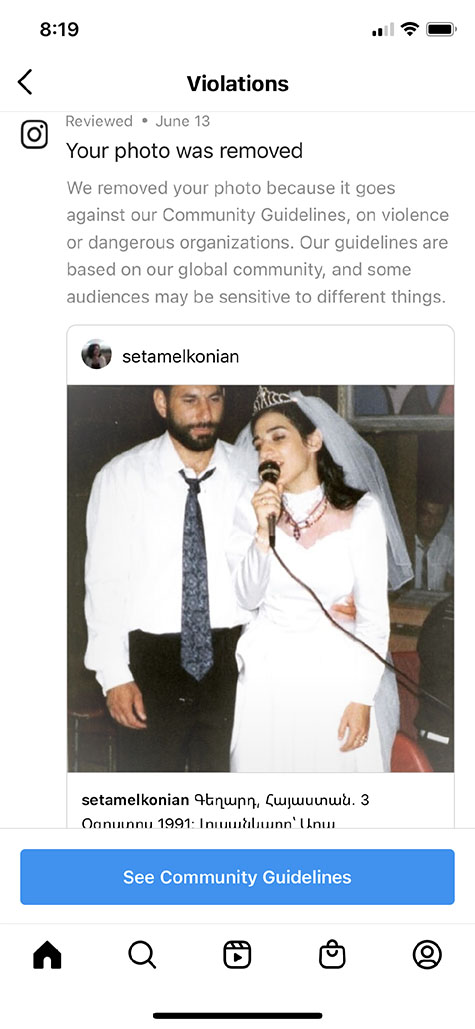

One by one, photos of my homeland, photos of my people, photos of my late commander husband, even photos of us two together in civilian clothes — are blocked by Instagram, followed by warnings. I wonder about my rights. I “Report a Problem,” I complain and explain. Photos get reinstated and unblocked. I get generic apology messages.

On the anniversary of his death, I post the black-and-white photo from the lapel pin on his soldiers’ fatigues twenty-eight years earlier. I tell the story, and very soon my Instagram account is gone. “Deleted,” the Instagram message says.

My truth seems defenseless against the arbitrators and perpetrators of untruths. My 120,000 Artsakh compatriots’ truth is invisible on the oil-rich Azerbaijani canvas. A fluid truth has conquered the social media space. Instagram’s mission statement claims “to capture and share the world’s moments.” My moments, though, do not count. Instagram creators claim that one can “Connect with more people, build influence, and create compelling content that’s distinctly yours.” But mine might be too “distinctly mine,” and cannot be permitted.

Facebook’s mission statement claims “to give people the power to share and make the world more open and connected.” Just not to all people. On every anniversary commemorating my husband, thousands of Armenian users’ Facebook accounts are flagged, receive warnings, restrictions, and blocks, even when their posts are reposts from mainstream media or government sites.

People send me screenshots of their blocked Facebook pages and Instagram accounts. I throw up my hands. I click the X on the right corner of my computer screen. The internet is folded. A clean white screen returns my gaze. I position my fingers on the keyboard. A line of black letters marches in smooth progression, making room for my truth.

Monte’s truth will resonate through the ages. He turned us away from victimhood, and toward renewed life. An Armenian giant. Thank you for this piece. He lives on in all of us.

Not a little ironic that neither Seta nor Monte were from Armenia. Seta is from Lebanon while Monte was from California. What motivates people to leave their country of origin to fight for someone else’s “freedom”? And how does Monte, a Californian, conclude that people thousands of miles away are his “people” anyway? Nationalism is a very confused and destructive ideology, and has caused rivers of blood to flow,…

Ask the Turks why they weren’t from Armenia. They are Armenian regardless of where they were born. You are confusing your version of nationalism with that of survival of a people who would have disappeared over a hundred years ago during the genocide…. Their effort to survive and flourish and the opportunity for the descendent of the genocide to make sure it never happens again is not nationalistic, it’s plain and simply called survival.

Perhaps you should study the Armenian Genocide before labeling survival as nationalism.

Identitarianism is justified when that identity is oppressed. Two examples: feminism, the civil rights movement in the USA.

The blinkered utterings of a white Liberal who has absolutely no idea what living as a persecuted people who have more than once been threatened with annihilation means. Armenians’ requests for help fall on deaf ears. The savagery of our destroyers is ignored. Armenians only have each other. THAT is why Monte, Seta and millions of other diasporan Armenians, the descendants of those who WOULD have been born in Armenia had it not been for unparalleled Turko-Azeri barbarism, feel compelled to help.

In the current geopolitical situation, as long as the main concern of the so-called “superpowers” (eastern & western imperialists) is their interests (i.e. Azerbaijan’s dirty oil/gas, and competing for only Muslim member of NATO), and some Armenians (including dishonorable authorities) have tendency to divide into “pro-Western” and “pro-Russian” camps, the Armenian people should rely on themselves only. So I wish we had a leader who could unite us and remind us about SARDARAPAT and MUSA DAGH uprisings. A leader like our hero MONTE MELKONIAN (RIP) who once said: “We do not believe in benevolent friends, the inevitable triumph of justice, or covertly and cleverly manipulating the superpowers. If we are to achieve national self-determination, then we ourselves, the Armenian people, will have to fight for it. We believe in the power of organized masses and in the capacity of our people to determine their own future. We believe in revolution.”

“If we lose Artsakh, we will turn over the last page of Armenian history,” Monte’s words sounded like a call to alertness for front line soldiers and for the entire Armenian people.

What’s ironic is our U.S. policy of defending “democracy” only when it suits our interest, and never when it doesn’t appear to. Armenia is the only democracy in the Caucasus region. I’m glad that you are curious, but you would’ve benefitted by a little research before passing judgement. The motivation to fight for people half the world away is due to a connection felt towards them because even though generations have passed, to many of us in the Armenian diaspora (a result of the Armenian Genocides of late 19th- early 20th century) they ARE our brothers and sisters. If we don’t fight for our cause of self-determination, and defend our people, our selves, no one else will.

I am not Armenian, but I am an admirer of the virtues of your brave and ancient people. In my country, one of the best ministers we ever had was the poet and economist Varujan Vosganian. Armenia needs now, more than ever, a hero following in the steps of the great Monte Melkonian (RIP). May the Lord save Armenia and all Armenians from all the traps and perils stemming from the terror of history!