Ghazi Gheblawi

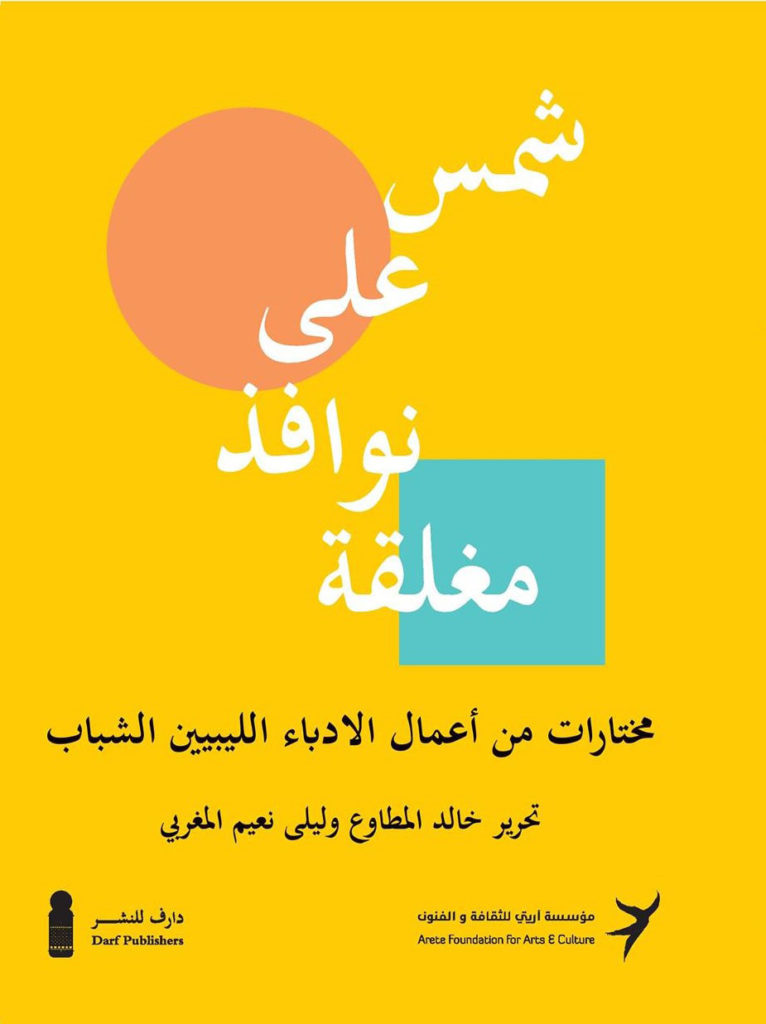

In 2017 Darf Publishers, an independent publishing company based in London, where I am a senior editor, published an anthology of young writers from Libya under the age of 30. The project was the brainchild of Libyan American poet Khaled Mattawa, through his nonprofit, The Arete Foundation for Arts in Culture. Launched in 2011 and funded within a few years, the Arete Foundation has organized and supported a number of cultural events and projects in Libya following the political upheaval of 2011. Edited by Mattawa and Laila Mughrabi, the anthology, titled A Sun Shining on Shuttered Windows (Shams ‘ala Nawfdh Mughlaqah), included 24 authors, many of whom began writing during the thawra. It was considered an exploration into new writing by the latest wave of Libyan writers who were breaking the norms of society and culture. Dubbed by its detractors as “The Yellow Book” for the color of its cover and used as a pejorative, A Sun was later banned in Libya and its writers faced abuse and harassment on social and mainstream media, which caused a number of the writers to leave the country or hide until the smear campaign against the book died down.

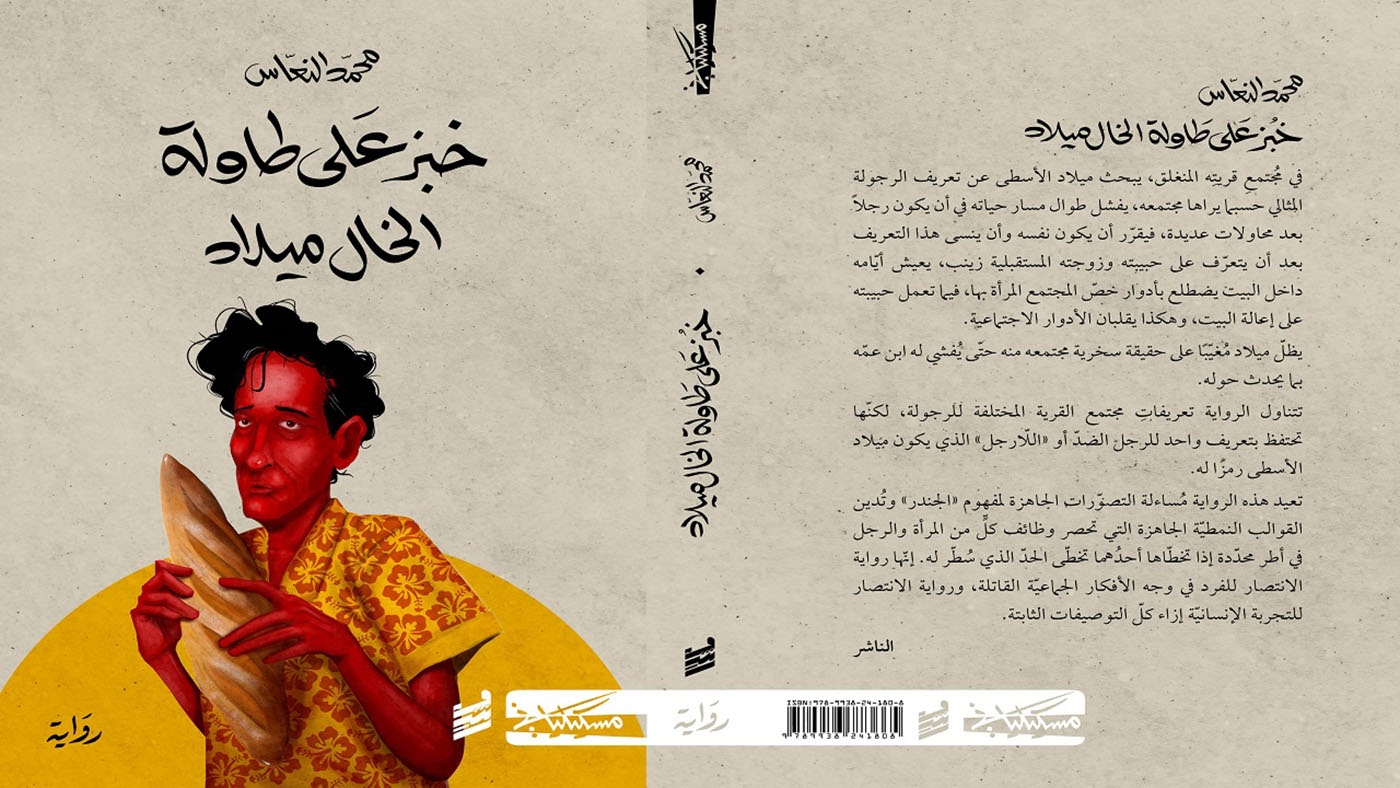

Mohammed al-Naas, winner of this year’s prestigious International Prize for Arabic Fiction for his debut novel, Bread on Uncle Milad’s Table, was among the writers featured in this anthology and it heralded the birth of a fully formed writer who had honed his skills for more than a decade, writing short stories, unpublished novels and most importantly, captivating articles of nonfiction and investigative journalism that explored the social aspects of life in Libya before and after the fall of the Gaddafi regime.

At the age of 31 Naas (born in 1991) is among the youngest writers to win the renowned prize that became since its inception in 2008 the most influential accolade in the Arab world, full of speculation, intrigue and its fair share of drama that haunts similar literary prizes worldwide. Naas represents the post-2011 generation of Libyan writers that began to form their individual voice during the dramatic political change that set Libya on the course to many social and cultural turning points, ushering in a decade of instability, war and chaos. In this upheaval writers found themselves less burdened with a political system that was overreaching, controlling and repressive of individual freedom of expression, while relegating this oppressive function to a myriad of local centers of authority and power, with rogue militant armed groups that don’t adhere to any ideological or political philosophy. While the last decade has witnessed a flourishing of creativity in the fields of journalism, media, literature and the arts, it has also seen repression and violence.

While he was exploring ideas on writing his first novel, Naas embarked on a sociological, cultural and historical excavation of the Libyan psyche and personality through a series of poignant essays and investigative articles that were published on his blog (Out of Reach) and several influential online Arabic platforms. These articles dealt with culture in Libya from folk singing, sayings, dancing and a critique of the Libyan mind. His articles were well researched, written with the eye of a documentarian, while maintaining a high sense of humor.

This social and cultural dissection prepared al-Nass to delve into discussing topics and ideas that were rarely mentioned outside casual social gatherings and local cafes. It was his ability to dig deep into the meaning of cultural attitudes that allowed him to lay bare some of the most sensitive issues while maintaining the style of a storyteller with condensed and short sentences.

His first attempt at writing a novel, Ensan (Human), which he wrote in 2013, was an examination of the history of violence in Libya through the eyes of a Gaddafi loyalist soldier during the 2011 conflict. It was posted online and Naas never managed to finalize a manuscript for publication. He recently confessed that he can’t go back to it anymore. He continued publishing short stories and in 2015 won the Khalifa Fakhri Award for Libyan Short Stories, which consolidated his skills as a storyteller.

That same year he resigned from his day job as an engineer to become a full-time writer and journalist, working as the editor of Huna Libya, an online platform on Libyan current affairs, supported by the Dutch public broadcaster Radio Netherland Worldwide. In 2017 he was forced to spend several months residing in Tunisia after a public backlash on the publication of the aforementioned anthology of young Libyan writers, subsequently banned from distribution in Libya. Several writers were harassed and driven into hiding, threatened by rogue militant elements in the country, leading one editor of the collection to seek asylum in Europe.

Naas has emphasized on many occasions that he began writing drafts of several novels before managing to write Bread on Uncle Milad’s Table (published by Rashm and Meskliani in 2021) in six months during Covid-19 lockdowns in 2020. The journey began a decade ago when, like many emerging writers, he wrote short stories, an essential feature of the Libyan writing scene across the past seven decades. In 2019 he edited and self-published his first collection of short stories, entitled Blue Blood, which dealt with the social and cultural challenges facing a new generation of Libyans after the 2011 uprising.

It was Naas’s fascination with the Libyan psyche, manifest in traditional sayings and local folk trends and attitudes, that led him to begin writing Bread on Uncle Milad’s Table . Gender roles, masculinity and social changes in Libya became the main issues to which he turned his attention. The novel hinges on a recent Libyan phrase “a family and its uncle is Milad.” Naas explains the origins of his fascination with the image of the “man,” manhood and masculinity in the Libyan mind in an article he published just before the publication of the novel in 2021.

He admits that he failed to find the origin of the phrase before 2011, as internet services were not so widespread in the country for it to appear on any Google search result. He also unsuccessfully attempted to uncover traces of the phrase in reference books on popular proverbs that he managed to find, which detail the relationship between a man and a woman. He explains that the phrase claims that the root cause of women’s liberation is not the absence of male authority, rather that this authority encourages this kind of “debauchery” in the eyes of society.

He says that “Uncle Milad is a danger to the identity and image of the man” — he is the anti-man as he likes to say, the man “who cooks for the woman in his life, dances with her, sings with her, irons her clothes, washes dishes, listens to her and cries for her wound and pain.” Naas says that this anti-man reveals his feminine side, and above all “encourages his female to be liberated from society’s authority” out of conviction not coercion. He concludes that “Uncle Milad is a disgraced man. The anti-man, a threatening image,” an image that Libyans agree shouldn’t represent the Libyan man.

Milad in the novel is a conflicted character who was shaped on one hand by society’s expectations and on the other by his beliefs and convictions that he has to break these societal norms and traditions. Naas researched his character to the extent that he delved into the world of bread baking and pastry making, which Milad took as a profession. He managed as a writer to use all his knowledge and skills to hold a mirror up to society and make it see its reflection. And as is the case of any expository writing, people didn’t like what they saw.

Shukri Mabkhout, Chair of Judges for the 2022 International Prize for Arabic Fiction, described Naas’s novel as written “in the form of confessions of personal experience. Its plethora of details is deftly unified by a gripping narrative, which offers a deep and meticulous critique of prevailing conceptions of masculinity and femininity and the division of work between men and women, and the effect of these on both a psychological and social level. It falls into the category of novels which question cultural norms about gender; however, it is embedded in its local Arab context, and steers away from trivial projections or an ideological treatment of the issues, which would be contrary to the relativism of fiction and its ability to present multiple points of view.”

Following the announcement of the award, and after a short-lived wave of praise and congratulation messages from the Libyan government and public, Mohammed al-Naas found himself at the center of smear campaign that targeted the novel and himself with the same elements that reared up in the past decade as custodians of “morality, traditions and norms,” condemning the book’s “explicit” passages and use of “indecent” phrases. Shortly after that, the Libyan Ministry of Culture deleted its congratulatory note from its Facebook page and issued a statement banning the sale and distribution of the novel in Libya until it acquires the “proper permissions” from official bodies.