The world quickly moves on. There was the devastating earthquake in Morocco, the worst in 120 years; there were the floods in Libya that killed thousands in Derna. There is the tragedy in Nagorno Karabagh, a conflict in which Azerbaijan is winning the narrative and indigenous Armenians are losing Artsakh; and now, once again, there is a war between Palestinians and Israel, instigated by Hamas, joined by other Palestinians, and fought with increasing brutality. And the world will move on, again. But let’s pay attention to this tragic Armenian story.

Seta Kabranian-Melkonian

By the last week of September 2023, the indigenous people of the Armenian Artsakh vanished from their ancestral land. The last of the elderly and individuals with disabilities trickled into motherland Armenia under the scrutiny of Azerbaijani forces. My compatriots left behind a history of millennia, multigenerational homes, and livelihoods. Most were given a few hours to pack and leave. Their pets were to be left behind, let alone the livestock and other animals. Day after day I stared on my digital screens, looking at my non biological family of thirty years. A family of 120,000 with whom I had shared a multitude of gains and losses. I valued their determination and cherished the democratic state they created and ran for thirty years. According to a decree signed by its president, the Republic of Artsakh will cease to exist on January 1st, 2024. I did not anticipate having to write this essay. I’d hoped for calm and peaceful times. I’d hoped for traditional weddings after the gathering of autumn crops in the villages of an ancestral land. I’d hoped for happy children going back to school on September 1st. All these thoughts wedged in my brain. For the reality in my traditional ancestral land is much bleaker than these simple hopes.

What is an ancestral land to the survivors of a massacre, a genocide, a Nakba?

As a child listening to the barbarous stories of the older generation, I thought this would never happen again. I believed in an equitable, just society where nations reserve the right to determine their own destiny. Where there is no room for violence, where differences are cherished, and justice and fairness prevail. Now close to the end of 2023, I have many reasons to feel how naïve and hopelessly optimistic I was.

In June I visited my ancestral land for the first time since the 2020 Azerbaijani offensive on Armenia and the disputed territory of Nagorno Karabagh, known to Armenians as Artsakh. For the first time in 30 years, I was unable to visit Artsakh on June 12th, the day my husband, the national hero Monte Melkonian, was killed in Artsakh.

In December 2022, and in violation of the Cease Fire Declaration signed on November 9, 2020, Azerbaijan blockaded the Lachin corridor, Artsakh’s only link to the outside world. Then, on June 14th, 2023, they blocked the road entirely, cutting off the 120,000 Armenian residents in Artsakh from their basic needs including food, medicine, hygiene products and fuel. Water and electricity were also scarce.

After the siege, my phone calls to loved ones living in the region were shorter and shorter.

“I took the last of my heart medication,” reported my friend one morning.

“I read about the man who died at the age of forty-five, of malnutrition,” I said.

“We have some pasta and rice left. Nothing else,” my friend told me.

We reminisced about our feasts of zhingyalov hats, a flatbread stuffed with wild greens, a staple of local cuisine born during a time of scarcity. During the first Artsakh war in the early 1990s, I accompanied my host to gather some 10-15 types of greens and wild herbs from nearby fields. As she chopped and mixed the greens, her husband brought a half-dome griddle to the backyard. He piled wood under the dome as his wife kneaded the dough. She lined the doughs stuffed with greens on the dome, three at a time. While the greens steamed inside the thin elongated bread, her husband emerged from the cellar with a bottle of red wine he’d made. Under the April sun that day I remember the illusion of peace.

During the recent ten months, farmers and villagers were targeted by Azeri snipers while working in their fields. Even the wild greens of open spaces had become unreachable for the residents of the region.

Following the massive Azeri aggression on September 19th, the fall of Amaras Monastery finds me off guard. After creating the Armenian alphabet around 410 AD, Mesrop Mashtots himself had taught at Amaras, located in the Martuni region of Artsakh. The creation of the alphabet had cemented the national identity of the Armenian people. How could history documented in black and white be questioned in 2023? How could history written in stone be questioned?

Azerbaijan’s continuous violation of the 2020 Cease Fire Agreement and cruelty won out. Under threat, the Armenian authorities not only conceded territories from Armenia proper, they also “recognized” Azerbaijan’s territorial integrity, which included the Artsakh region.

I remember February of 1988, when the first demonstrations started. In the era of Glasnost and Perestroika, the Council of People’s Deputies of the Nagorno Karabakh Autonomous Oblast voted for the reunification with Mother Armenia, practicing their right to self-determination. That right still remains, no matter how painfully the west chooses to neglect it. The land belongs to the people who lived on it for millennia, generation after generation, before the stroke of a pen or a line on a map erased a long history. There is no oil, no gas, no mines, no riches. There are rugged mountains, ancient monuments, and the age-old history of a nation.

In early September, I often read headlines about cargo flights full of weaponry arriving in Azerbaijan from Israel and Turkey. I also read about the concentration of Azeri troops along the borders of Armenia proper and around Artsakh. Breach of the Cease Fire agreement is not new for Azerbaijan. But Armenians in Artsakh had nothing to rely on. No help was to arrive from any side, including its own Armenia.

Authorities in Azerbaijan spend millions on their PR and on buying out influence in Europe and the West. Deeply experienced trainers from Turkey and Israel have tutored their spokespersons well when it comes to the right words. I often hear terms like “integration,” and “rights and security” in reference to the Armenian population of Artsakh. Words that are incompatible with the documented torture and cruelty Azeri forces had practiced during their unprovoked attacks on the civilian population.

The Military Trophy Park in Baku, where helmets of dead Armenian soldiers and mannequins of injured and dying Armenian troops are displayed doesn’t indicate any sign of the will to “integrate” or respect of “rights and security” of any Armenian.

I remember the early phase, the 1990s Artsakh war when fond memories of Azeri neighbors and human relations were still fresh. Some of us, the grandchildren of the Armenian Genocide survivors, had come to lend a helping hand to our compatriots in their fight for self-determination.

On a relatively peaceful April day in Artsakh in 1993, I decided to take a walk into town. Gravel and dirt crunched under my Armenian-made leather boots. I passed by the remnants of a stone shop, its shell-pocked roof like a video game monster’s mouth. I walked by the Soviet Era half-empty department store, its uninviting dusty cement floor a triangle under a half-open door. People I didn’t know greeted me. I smiled in return and made small talk. Shared ancestry, motherland and national struggle brings us close. Near the town square, a group of children came along, and I recognized a well-built adolescent girl. At a New Year’s event I’d organized for the kids, someone had pointed at her when I asked about the children of mixed marriages. After the bloodshed, mixed families faced the impossible decision of relocation or separation.

In the town square, the stout girl fell into step beside me. “Her father is a Turk,” whispered a child pacing at my side. Azeri and Turk are used interchangeably. Most often, all enemies are referred to as Turks.

“My father is not a good man,” she said, perhaps hearing the young boy.

I noticed her innocent effort to impress me. I was the spouse of a victorious commander. I must hate the enemy.

“Why is he not a good man?” I asked the girl.

She shrugged. She hadn’t seen him for several years. She must have only been a child when she saw him leave.

“Your father is not a bad man just because of his ethnicity,” I told her.

I considered my unfashionable approach. The first victims of ruthless rulers are their own people. A parent deprived of seeing a child grow. A family forced out to a foreign land so they could stay together. Silence as the only answer to, “Where are you from?” An identity hidden behind a non-mother tongue, or a new, foreign passport.

In 1992, after a battle, my husband Monte was informed that a villager had beaten an injured Azeri soldier. “Take him to the Badval (an underground storage that served as jail),” he commanded. His soldiers hesitated.

“But Monte, the man lost his nephew in battle. He was very angry,” a soldier said. “Take him to the Badval!” Monte repeated. “You can never, ever hurt an unarmed, injured soldier.”

Lessons were learned, and in the following years I never again heard of a similar incident, at least in Martuni Region.

During the same period, after another battle, the military hospital doctor informed Monte that an injured Azeri soldier would die if he did not get blood.

“Who would volunteer to give blood?” Monte asked his soldiers. Noticing their hesitation, he pulled up his shirt.

“I’ll go first,” he said. His soldiers followed him.

Somewhere in Azerbaijan, Monte’s blood is running through the veins of a former soldier.

Returning from Karvajar in April 1993, I accompanied Monte to Artsakh’s capital, Stepanakert, where he had a meeting. I had heard about Azeri patients recovering from injuries. Monte’s driver took me to the hospital. An older woman lay in bed, with a younger woman tending her. The woman would recover, and the family would be exchanged for Armenian hostages in Azerbaijan.

During my visit I noticed an Armenian woman sitting at a table next to the window. There was a bag of food at her feet.

“Did you know them prior to the war?” I asked.

“No. I just thought they could use some additional food,” she said.

I looked out the window. Children were playing in the yard of the kindergarten next door.

“Our kids are among those,” said the younger Azeri woman. “They are playing in the kindergarten until grandma gets better and we get exchanged for Armenians held hostage in Azerbaijan,” she said.

I imagined peaceful times when mistakes were accepted and corrected. When the rights of people for self-determination were respected, not reprimanded.

The Republic of Artsakh declared independence on September 2nd 1991. It was never part of the Independent Republic of Azerbaijan when the latter declared its independence in October of the same year, following the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Over and over again, I try to find something to hang onto. Are there any precedents we can learn from? There are. Places like Kosovo and East Timor, where I once searched for a job. Despite the complexities, I know Artsakh cannot survive under an oppressive regime whose brutality and human rights violations are well documented, long before the Artsakh war. Now Artsakh’s very existence is in question. The blood of innocent people is on our hands, we, the taxpayers and residents of the west, whose representatives, the likes of Ursula van der Leyen, do not even blink when discussing full cooperation with a leader whose country is one of the most corrupt in the world, as ranked by Transparency International. No one questions the source of Azerbaijan’s ruling family’s wealth, their real estate empire in the UK and other European countries. No one questions the findings revealed by the Pandora Papers, or why the profits from numerous offshore companies, or oil and gas revenues never reached the people of Azerbaijan.

While I write these words, my beloved Artsakh is completely deserted. For ten months its population lived in a new Gaza, an open-air prison where its elderly and children were trapped. Communication was cut between villages and towns as every family searched for lost loved ones. Thousands of men are still subject to abduction to face trial in Baku for defending their homes and families.

Video clips of Azeri soldiers shooting at peaceful villages, photos of beheadings and tortured bodies posted as heroic acts on social media drain the last drops of hope for peaceful co-existence. For the last few years, the enemy, the masters of emotional oppression, have been sowing hatred not humanity. When one side gives orders and threatens war, there are no negotiations.

From the time that Nagorno Karabagh was an Autonomous Oblast within Azerbaijan, Azeri authorities denied its people’s rights to self-determination. The ten-month blockade of Lachin Corridor is a gross violation of Human Rights. In August, the former chief prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, Luis Moreno Ocampo published a report in which he wrote, “There is a reasonable basis to believe that a genocide is being committed.” The U.N. convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, Article II C defined genocide as: “Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part.”

On September 20th, my friend called from Artsakh.

“Where are you?” I asked, surprised she had managed to call.

“We are all outside. We don’t have electricity at all. Everyone brought down the little they have left. We put a stove in front of our building and cooked some food. Wheat and potatoes. I drank tea,” she said, in a manner indicating that tea was a big treat.

“It’s good that you are all together. Your phone is working,” I uttered, just to say something.

“The only place with a generator is the morgue. They let us charge our phones there. When I entered the building, the employees told me not to look to my right or left. I did. Unidentified children’s bodies were piled up in there,” she said.

Dumbfounded by the developments, I searched for words.

“It’s quite bad,” I said. “Have you heard from your family in the region?”

“Our town is surrounded. Some villages are gone, some are surrounded. There is no connection between any of us,” she answered.

“There is no connection from outside either,” I said, not knowing what else to say.

“We are cut off from the outside world. What are they saying? What will happen to us?” she asked.

“No one knows,” I answered. I heard noises in the background.

“Could you put your camera on?” my friend asked. I touched my screen.

In the darkness, shadows moved around the orange fire of a stove.

“It’s Seta,” I heard, from a voice I didn’t recognize. I paused. I took a deep breath. There was a knot in my throat.

“Stay well. I love you all,” I said.

Now you tell me, dear reader, after 30 years of bloody wars, will there suddenly be a peaceful “integration” of the two nations? Will there be good faith and peace when ancient monuments are being destroyed to erase history even as I write these lines? With no due process, will there suddenly be a peaceful cohabitation in an ancient land where an abundance of ancient monuments attest to centuries of Armenian presence?

Major media outlets in the west still refuse to call the situation by its right name. Azerbaijan announced that it “reclaimed territory” from “separatist Armenians” and their “illegal regime” who did not want to “integrate” and “chose to leave.” To call it by its right name, a territory inhabited by Armenians since 189 BC, is subjected to ethnic cleansing because its population dared to practice their rights to self-determination, thus were threatened to death by genocide or forced to flee.

In the face of the indifference or at best the lip service of the West, Azerbaijan didn’t leave an option but the exodus of the indigenous people of Artsakh.

Thank you for this important and utterly heart-wrenching piece. As you describe “photos of beheadings and tortured bodies posted as heroic acts on social media,” it shocks the conscience to watch history repeating itself, now on full display for the world to see, and with little if any level of humanitarian intervention at the recent atrocities in beloved Artsakh.

My deepest respect and gratitude go to Seta Kabranian-Melkonian for her conviction of character and courage to write the un-writable. “Never again” would ring out as but an empty slogan if not for documentation such as this, which both timestamps the historical record and holds the human race to account… in Artsakh and amid every corner of the planet.

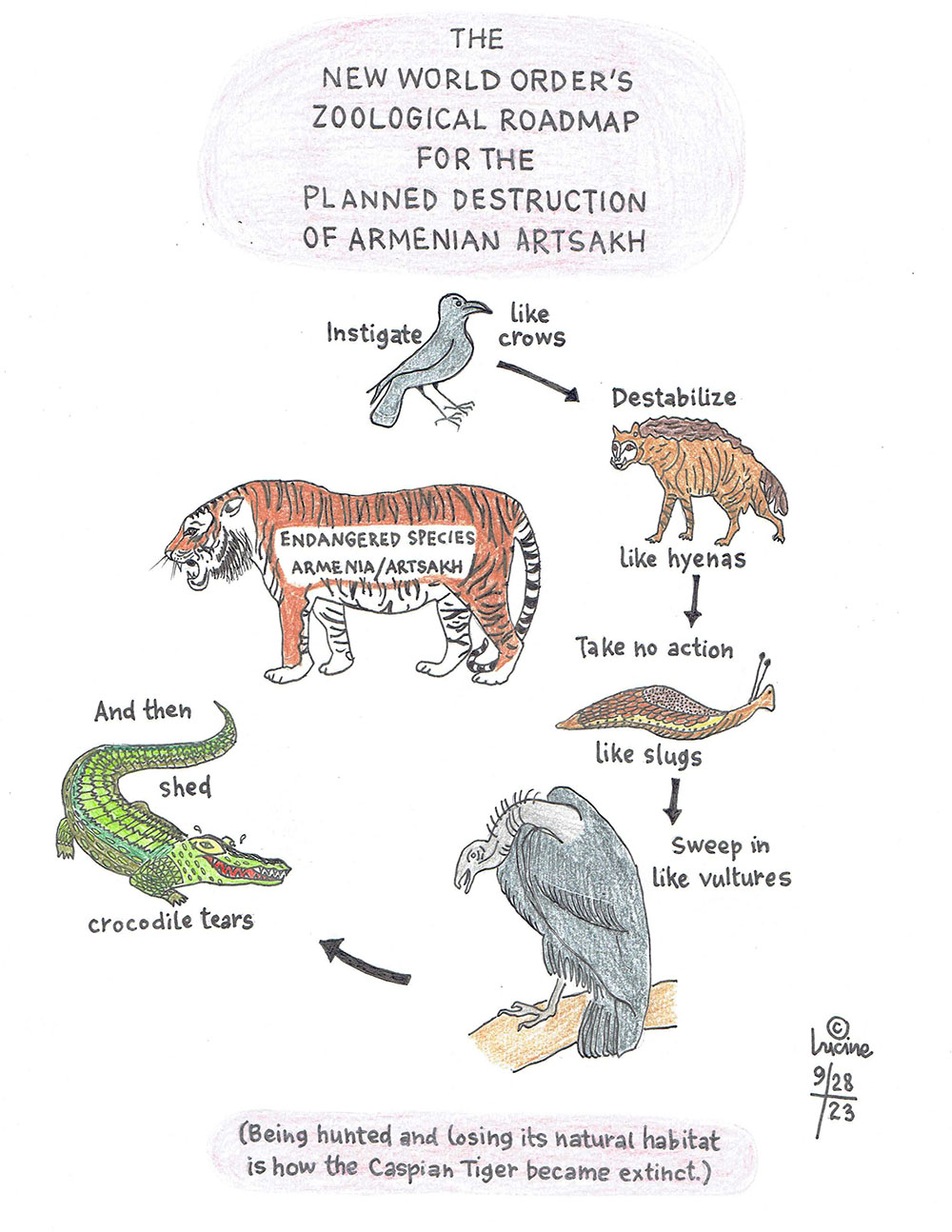

Nothing but praise for the sheer genius in the editorial cartoon work of Lucine Kasbarian. Abris! and tears.