In her column "This Arab Life," Amal Ghandour looks at the absurdity of Trump's so-called "Board of Peace," and Mr. Ali Shaath, the commissioner of the newly established Palestinian National Committee for the Administration of Gaza.

Listen to this column.

In times of darkness, of turmoil or oppressive stagnation, of a political and personal fog so dense that you cannot see beyond your next thought, you come across a small moment that betrays a much larger meaning. It could be a statement, an interview, a speech, a sight, perfectly ordinary, or even laughable, that acts as a window onto a truth of profound import.

Mr. Ali Shaath, the commissioner of the newly established Palestinian National Committee for the Administration of Gaza, sat for his first interview last week. The ten-minute conversation was a telling reprise of the 1970s: the high chair, the ornamented room, the interviewers’ soft balls, and the banalities issuing from the man’s mouth in response. By minute 8:08 — right after the journalist had furnished us with a profile of his guest — the 66-year-old civil servant still felt the need to stress that, indeed, “I am an engineer. I graduated from ‘Ain Shams University with high distinction.”

Like a stage set, the room, the chair, the man, the vacuous smile, the words themselves, formed a choreography of demise: in the wake of genocide, a shuddering absence of Palestinian leadership that threatens the very resilience of a cause in its most vulnerable hour.

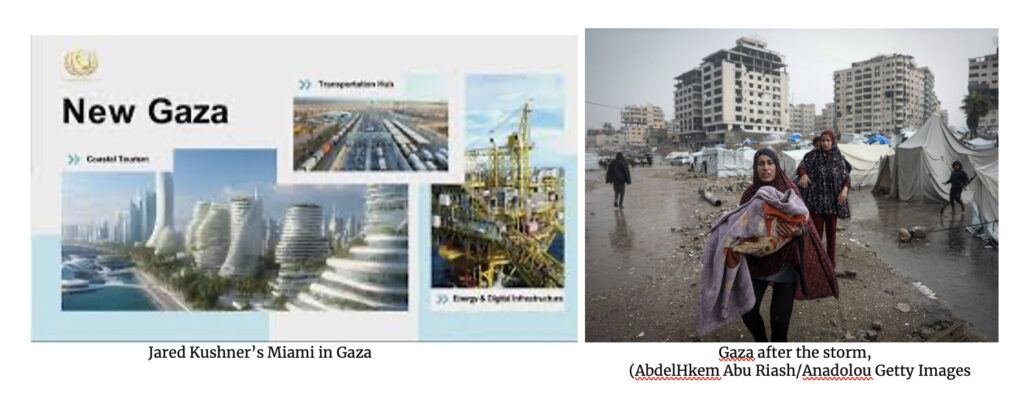

An Israeli and American effort breathtaking in its audacity is underway. It seeks, at once, to neutralize the devastating international repercussions of Israel’s mass slaughter and to pave the way for erasure in both Gaza and the West Bank. Erasure of the crime itself, of presence, of history, of promise, and thus of a Palestinian future in Israel-Palestine. Such a project requires its architects and generals, its advocates and apologists, its cheerleaders and foot soldiers, its bureaucrats and props. To watch Mr. Shaath — no doubt, Mahmoud Abbas’ whispered choice — spew drivel and bromides was to behold an embattled, pursued, exhausted Palestinian people abandoned to their wits in the harshest of times. A familiar story for decades, perhaps, but now of potentially ruinous consequences for their cause on its sacred ground, as it finally wins much of humanity’s nod.

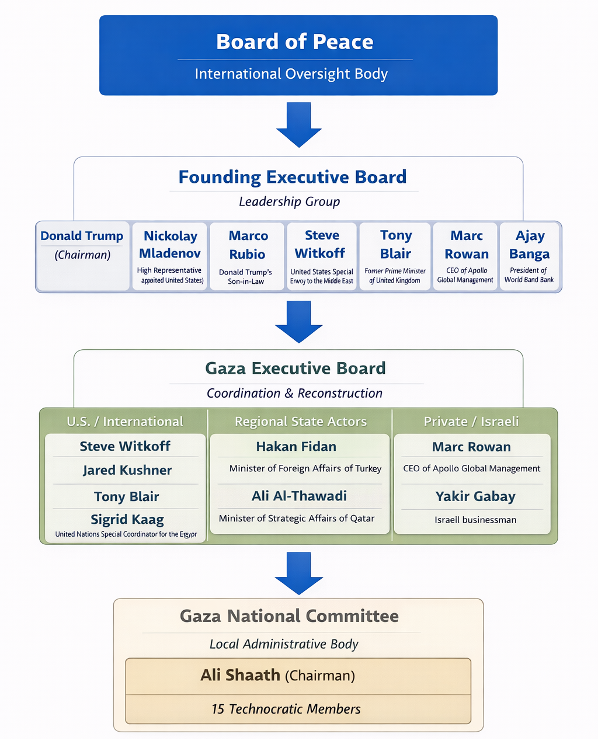

This is a conspiracy, with all its hideous details publicly displayed as a showcase of how the once unthinkable becomes permissible and actually attainable. I think of it as a road show of sorts; a Trumpian rollout, starting in the US itself. The obnoxious exercise of power is creed: matter of course, automatic, visceral. The supposed governing structures themselves are bizarre innovations on an old colonial construct: a self-appointed “CEO of the world” presiding over a Board of Peace, complete with a one-time billion dollar fee for lifetime membership. Beneath it sits its Founding Executive Board, which in turn oversees the Gaza Executive Board, which itself rules over the natives: Ali Shaath and his committee, whose authority is nil but whose role is to legitimize what is scandalously illegitimate.

The measure of this categoric condemnation is a very simple question: which member of these boards, including the CEO himself, would accept such a governance apparatus imposed on their people? A question for Shaath and his colleagues to answer, perhaps, with the help of his high distinction diploma from ‘Ain Shams. “But what was to be done?” they might protest. An answer that so perfectly captures the catastrophic failure of a national liberation movement.

Thankfully, the distinctly Trumpian quality of this unfolding scene saves us the trouble of clearing away the clutter of euphemisms that typically obscure imperial intentions. It also reveals itself against a backdrop of arguably irreparable ruptures in the international order. We are all at sea, a condition ill-suited to the durability of colonial ventures of a particularly unstable nature.

Thankfully, the distinctly Trumpian quality of this unfolding scene saves us the trouble of clearing away the clutter of euphemisms that typically obscure imperial intentions. It also reveals itself against a backdrop of arguably irreparable ruptures in the international order. We are all at sea, a condition ill-suited to the durability of colonial ventures of a particularly unstable nature.

Admittedly, the garish grandiosity and farcical character of the entire scheme does invite comic relief, but the effect of them, when we superimpose them on the current dystopian realities in Gaza, acquires a decided register of horror.

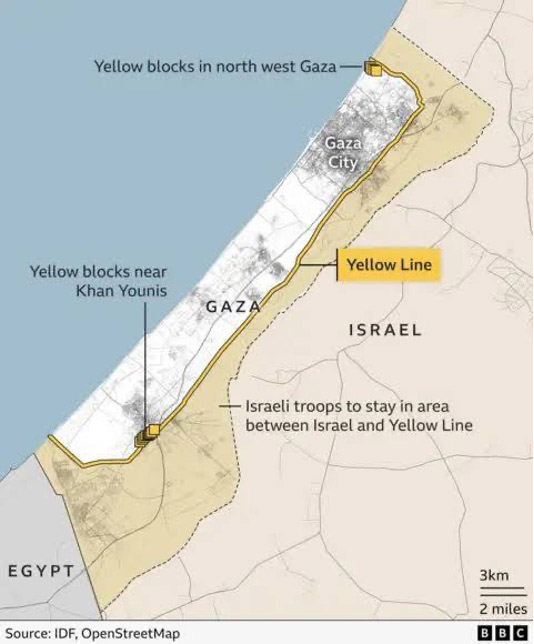

On the decimated strip of a decimated people, Israel is already implanting its greater self. In the East, on the 58% of Gaza it occupies, it is rapidly building military bases, roads connecting to settlements inside Israel, and “invitation-only” encampments for Palestinians. Those with their ears close to the ground suggest these are reserved for its favorite gangs and their families. Iterations of this Israeli method have long been rehearsed in the West Bank, in ways Palestinians know too well but the world too easily misreads or ignores.

Against this frightening backdrop sat Mr. Shaath, all talk and trousers, regurgitating platitudes from another age. Regrettably, a very small moment with such a large meaning.

On Another Note

In a stunning essay in the London Review of Books, Adam Shatz writes about America, his home country. In his anguish (and if only in his eloquence) he reminded me of my own embattled Levantine self.

I am an avid reader of Shatz, one of America’s leading public intellectuals, and I have never encountered him quite this intimate on the page. He opens with James Baldwin, of course, and end with a note of hope — and shame.

The very word “America” remains a new, almost completely undefined and extremely controversial proper noun,’ James Baldwin wrote in 1959. ‘No one in the world seems to know exactly what it describes, not even we motley millions who call ourselves Americans…

Since the 2016 election and especially over the last year, I’ve tried to love America with sorrow, as Beauvoir did. I’ve reminded myself of the emancipatory potential of its founding ideals, underscored by James. And I’ve returned again and again to the prophetic words of Baldwin and King. But what I mostly feel these days, as I look at the disaster unfolding in America and its horrifying repercussions throughout the world, is an intense sense of shame. Shame isn’t a pleasant emotion, but any honest reckoning with what my country has become has to start with it.

If you are not a subscriber to the London Review of Books, here is Shatz delivering the same reflections to a live audience. Your weekend is richer for it.

Amal Ghandour’s biweekly column, “This Arab Life,” appears in The Markaz Review every other Friday, as well as in her Substack, and is syndicated in Arabic in Al Quds Al Arabi.

Opinions published in The Markaz Review reflect the perspective of their authors and do not necessarily represent TMR.

![Fady Joudah’s <em>[…]</em> Dares Us to Listen to Palestinian Words—and Silences](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/SAMAH-SHIHADI-DAIR-AL-QASSI-charcoal-on-paper-100x60-cm-2023-courtesy-Tabari-Artspace-300x180.jpg)