TMR Interview

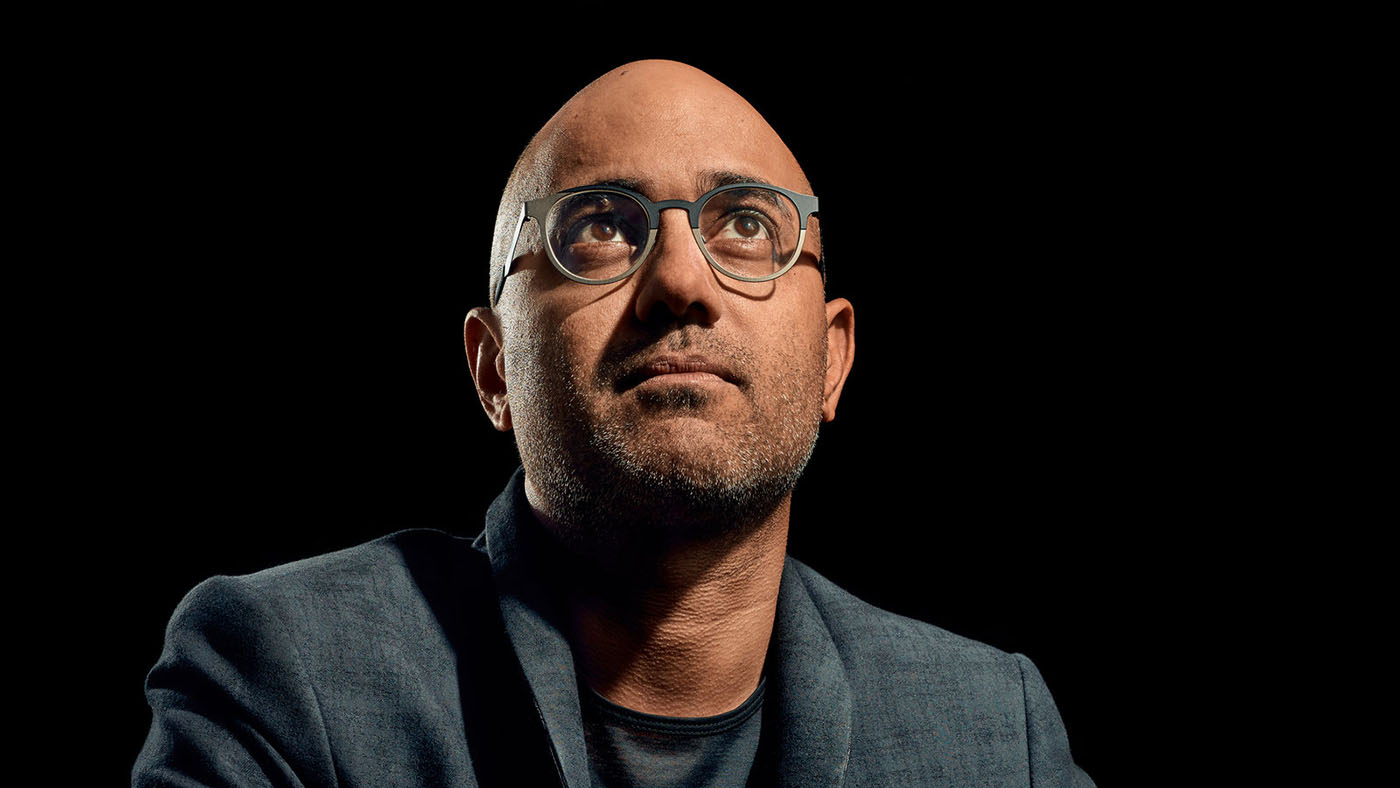

Ayad Akhtar

Interviewed by Jordan Elgrably

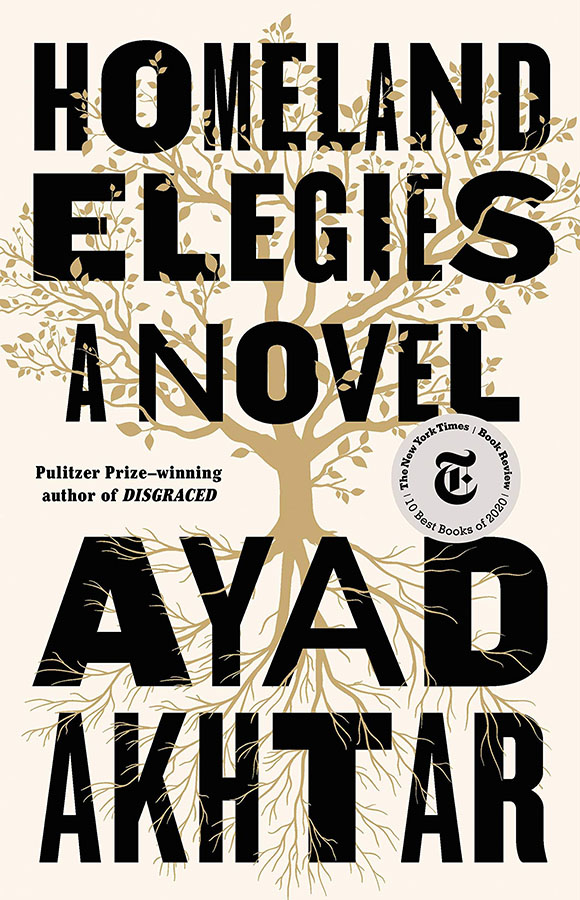

This interview with playwright and novelist Ayad Akhtar took place on the 14th of September, 2020 — the same month that I launched The Markaz Review and only a few months after The Markaz definitively closed shop in Los Angeles as a cultural arts center, due to both the advent of the pandemic and the lack of sufficient funding. Akhtar and I spoke to each other via Zoom from our respective homes in New York and Montpellier. I had just read and reviewed his second novel, Homeland Elegies, for the Los Angeles Review of Books. Akhtar won a Pulitzer in 2013 for his play Disgraced, while Homeland Elegies made 2020’s 10 Best Books lists of both the New York Times and the Washington Post. Ayad Akhtar is the current President of PEN America.

Jordan Elgrably

Ayad, for those who may not be familiar with your work, how would you introduce yourself; what should we know about you?

Ayad Akhtar

Nobody’s ever asked me that question, Jordan. I’m a playwright and a novelist. I’ve also written a lot for the screen. I think of myself as a dramatic storyteller, basically. And I think of myself as writing about the American experience. Of course, I think I get pegged, understandably perhaps, though no less irritatingly, as writing about Muslims. It’s not that I’m not doing that; it’s that I’m writing about people and they just happen to be Muslim. And I’m writing about America, writing about capitalism, I’m writing about murder, I’m writing about love — I’m writing about colonialism, I’m writing about all kinds of stuff. I guess that’s the slippery way around the question. And I’m sure that you were offering it up so that I could slip my way through it [laughs].

TMR

Well, yes, people who know your work know that you’re Muslim. But I intentionally asked that question because I had the feeling that you see yourself as a writer, number one, and American number two, and perhaps all the other things — three, four, five and six — and you don’t necessarily walk around with this idea that Muslim is tattooed on your forehead.

AKHTAR

On the contrary, within my own community, I define myself as somebody who’s in opposition to some of those sort of groupthink currents that my father would describe as Muslim. And I don’t know that I would describe him that way. But I certainly grew up in a household where certain elements of let’s say the Umma’s consciousness was something that my father really found objectionable, and that I learned to look at with some skepticism. Within that context, I wouldn’t actively embrace a Muslim identity at all. On the contrary, I would embrace an oppositional identity within that community. So it’s a very funny dilemma to then be cast as the Muslim American writer. It’s fine — it’s all good. I have no problem with it at the end of the day, but It does speak to all levels of complexity, you know.

TMR

And that’s certainly true in your novel, Homeland Elegies, that we’re going to dig into here. I just want to point out that we’re talking on September 14, 2020. This year hasn’t quite quite turned out as we imagined it has it? No. In fact, in my review of your novel in the LA Review of Books, I referred to our time as pre-apocalyptic. How do you feel about the year of the pandemic? And what lies ahead?

AKHTAR

I can’t remember where I read it, but I read somewhere that this year started as 1918, and then it was 1929, then 1968, and now it’s 2020. Who knows what historical, traumatic experiences are going to get recapitulated between now and the end of the year? We may be in for quite a doozy., I mean, it’s funny, it’s 19 years after 9/11. And I just did an interview yesterday or two days ago with a major radio program in which I was trying to speak about the genealogy of the history behind 9/11 and the continued American confusion or lack of awareness of the extent to which American foreign policy has not only played a role in how 9/11 came to be, but also that ignorance if you will, for lack of a better word, is substantially the cause of a post 9/11 reaction that literally destroyed the world and displaced 35 million people. And there’s this continued inability to even countenance an adult conversation about history 19 years after 9/11. It’s just astonishing because I was talking about this and the interviewer says, oh, just to be clear, you’re not condoning mass murder? Because I’m talking about the history behind 9/11.

TMR

Such a lack of subtlety in that question. As we know, there were no Iraqis in the attack on 9/11, and what we did to Iraq is obviously criminal. Why doesn’t that come into the consciousness of your “educated” American journalist?

AKHTAR

The blind spot is so enormous, you could fall into it for an entire career and not be any wiser or better off for having fallen into it. And it’s a blind spot that I’m trying to avoid falling into, even though I keep getting shoved into that blind spot — it’s obviously subject in part of the book.

TMR

Let’s talk about that. Homeland Elegies is about an American playwright who happens to be named Ayad Akhtar and his Pakistani immigrant cardiologist father, who has a professional and collegial relationship with Donald Trump. In the novel as in real life, the main character won the 2013 Pulitzer Price for Disgrace. Was this book a case of perhaps a playwright wanting to break the fourth wall?

AKHTAR

It was the case of a writer who felt that a straight third person narrative or an obviously fictional narrator would not be able to use those techniques to get my language and my consciousness around what’s happened to America. I would not be able to write about contemporary life in a way that could rival the insanity of our unreality. The only way to do that was to really try to find a form that was going to blur the line between truth and fiction in the way that it has become blurred, you know, across our societies. The other way of thinking about this was that it didn’t seem to me there was any way to write about what’s going on in the world today without it coming off as satire. And the only way to avoid the satire was to pivot to memoir, and to start playing this trompe l’oeuil, if you will, no pun intended. It’s a trick of the eye.

TMR

Funny how that sounds like you were saying something about Trump.

AKHTAR

Trompe l’oeil, tricking the eye if you will, is one of the things art can do, one of the great pleasures it gives us is that of mimesis — the illusion of reality. To be able to play with that, in this time of the deep fake, seems to me a worthy formal investigation.

TMR

As a reader, I felt for quite a while that you were writing an autobiography, or a memoir, but that you were telling us it was a novel, and I kept disbelieving the novel, saying, no, no, this sounds so much like what I know — the little that I know — until I came across a couple of points where I realized that we were having fun. And then I knew that it was definitely a novel. One was when you were in a theatre and having sex with a girl named Julie. That sounded like quite the scene there. And I thought as I read, I wished that had happened to me [Akhtar laughs]. And then the character whose name escapes me right now, Riyaz? he sounded like a bit of embroidery, but the rest of it was so convincing, especially all this stuff about your father, the father character. I’m wondering what the impulse was that took hold of you, when you realized that you’re writing something that was going to be a novel? Were you keeping a diary and then you decided that you’re ready to write a novel or did you make some plan? How did this all come about?

AKHTAR

I was headed to Rome to the American Academy, for a couple of months to do some work. And I thought I was going to write a novel — a very short novel about my father, or about a doctor and father who is dealing with a malpractice lawsuit in western Wisconsin. And that’s actually a narrative that ends up in this book. But as I was writing this novel in Rome, I realized that there was no way to write about my father’s experience without the intervening Muslim filter.

For him, Islam was not an issue, it was nothing he spent any time thinking about, so to write about his life in America is not to write in any way about Islam, it’s not relevant to his life, it wouldn’t be relevant.

And yet, I couldn’t seem to write in a way that was going to exclude this lens that I could feel was going to be put on the events and that I had to account for. So, I put it aside and thought, I don’t want to write this book — I don’t want to subject this character to yet another sort of intervening filter that has absolutely nothing to do with anything I’m interested in writing about, or anything that’s accurate to the fundamentally existential and social preoccupations that I wanted to explore.

There I was, reading a lot of classical stuff; I was reading Livia, Machiavelli, and Tacitus. One night I was in a library at the American Academy and I found the collection of poems by Leopardi, and I open “The Conti,” and the first poem is entitled “To Italy.” It’s an exhortation to his fellow Italians to remember something about their history, and to reflect on what they have become. I remembered thinking, a year after Trump had been inaugurated, and Newt Gingrich was across the street and his wife is the ambassador to the holy Sea to the Vatican — their residence is right across from the American Academy…I had been thinking about the politics, my mother passed away, my father was showing signs of decline, and I was thinking about what had happened to America, what had happened to my parents in the 50 years that they were here and what had happened to all of their kids, myself included, and what did it say about what America was for them, but what it became? What was that story?

So anyway, I read this poem by Leopardi and I thought to myself, would I be able to find a way to address my fellow Americans as he does in this poem to Italy; could I do something similar? I went to bed with that thought, but no idea if it was a possibility. I woke up the next morning, and the first words of The Overture, which is entitled “To America,” were already coming out of me. It was as if I had been gathering kindling for a lifetime, and there was an igniting spark. I didn’t even know what it was. And then suddenly, the writing, the voice just started to pour out of me.

TMR

Excellent. Homeland Elegies is as much a critique of post-Reagan capitalism, as it is the United States oligarchy from around ’79 until Trump, and your account begins with the character of someone named Mary Moroni. I assume the name was changed, but it’s your literature professor in college. And I quote, “America had begun as a colony. And as a colony, it remained that is a place still defined by its plunder, where enrichment was paramount and civil order always an afterthought.” When I read that, I wondered how as the child of brown immigrants do you participate in that reality, in this land that is founded on this colonial heritage of 1492 and the Spaniards and the Brits, and the plunder, that goes from killing the Indians to enslaving Africans to Wall Street and plundering the middle class. There’s a thread through that. The character Ayad and yourself are, like me, first generation Americans, basically brown people in a white country (my folks are Moroccan on one side, and yours are Pakistani). How do you participate in America? How do you make the reality work?

AKHTAR

I hear you and thank you for illuminating that dimension of it. I’m not sure that the brownness was of any relevance to the professional immigrants who came here to benefit economically in the late ’60s. There may have been some social exclusion, but I don’t think there was any sense of solidarity with those of the United States of plunder. I think that there has been a rise of successful immigrant professionals and entrepreneurs. And the intervening 45 years demonstrate the universality of the American model of plunder, America as an equal opportunity employer, for those who want to get rich — if you really want to get rich, you can. And that’s what American freedom really means. On some level, the story of America’s allure, both actually, and certainly for my parents, was one of opportunity. And that opportunity was what? economic opportunity. It’s not as if they couldn’t have gone to Britain and been just as “free,” whatever that means. We tout American freedom as if it’s exceptional in some historically unique way; I’m not sure that we’re any freer here than folks are in Montpellier or Denmark or wherever. What is unique is the freedom to make money, and the lack of shame around that. So that’s the story of the book, in a way: America as the land of money.

TMR

It is and we definitely feel that with the various anecdotes and stories that you share. But at the same time, we get the impression through the book, beginning with the Iranian Revolution in 1979 — you mention a number of different historical periods up to 9/11 — and obviously, 9/11 was one of the most egregious pieces of recent American history that made living in the US much more difficult for Arabs and Muslims, and anybody who looked like they came from that part of the world. How much of that 9/11 angst affected you?

AHKTAR

A lot. I mean, I think I write about it pretty honestly — yes, there’s the intervening filter of fiction but the essence is all true. The book argues that America — that the crumbling Republic that we are now experiencing, that even my difficulties as a Muslim post-9/11, did not prepare me to see clearly what had happened to this country. Even those difficulties, even the victimization, even the persecution and the exclusion and the rampant stupidity around all of that did not prepare me to see just how abject the nation had become. What finally made me see that was when I started to see what had happened to all of us. The argument in a way of the book is that yes, I’m Muslim; yes, I’ve had a difficult time post 9/11. Yes, those difficulties stand in for much larger historical issues, both within the nation and without; but actually, what has happened to this country — which is, of course, you know, Trump isn’t the ultimate symptom of it — that happened to all of us, it didn’t just happen to the outsiders.

TMR

Right, right, right. Was your father in fact, pro Trump? And how did you deal with that, or how do you deal with people in the family or friends rooting for him, in 2016, and are they still doing that?

AKHTAR

In playing this elaborate game of truth and fiction with the reader and sort of like the hermetically sealed, if you will, enclosure of the trompe l’oeil that I am concocting or at least proposing, I have for the time being decided not so much to directly speak to the correspondences.

TMR

But one had a sense anyway that there was another America that was emerging with the movement that was spearheaded by Bernie Sanders, which said, we care about each other, and we care about everyone. And we can’t just be greedy capitalists — as if to oppose the “greed is good” mantra of the Wall Street movies.

AKHTAR

I do think I do think that’s a rising sentiment in this country, but we’re going to need more time for it to really take root. I think the roots are still shallow, ideologically speaking. The critique of collectivity, of collective life in this country, is deep. And the suspicion of any abridgement of individual rights, whether it’s the individual right to make as much money as you want, or use whatever bathroom you want. The abridgement of those individual rights for the sake of a collective good, is something that is considered anathema to the essence of the American project.

TMR

Let’s talk about something more personal to you. After you’d won the Pulitzer, did that change your life in any substantial way?

AKHTAR

Actually, people started paying attention to me — I could never get anybody to read anything I wrote, but after I won the Pulitzer, it changed everything in the sense of access. It enabled me to have a career really, and I was incredibly fortunate in that way. It also put a lot of pressure on me for everything that I’ve done after that, and it’s a pressure I’ve relished. I feel like it’s pushed me to take bigger risks, to think more deeply about things because I know there’s going to be more scrutiny.

TMR

Now that your second novel, Homeland Elegies is out, how are you feeling about the book as a piece of work, have you begun to sort of let your hair down so to speak?

AKHTAR

I don’t have any hair, Jordan, but I see what you’re saying. Obviously, time will tell, right? We’re still close to publication. I wrote the book without knowing whether anybody would want to read it, because it is such an unusual structure. I knew that I was writing it substantially because I had to. And the simple fact of having allowed myself the freedom to do that has been transformative in some way. I don’t know what the benefits or the pitfalls will be ahead, because of that freedom that I accorded myself. But I definitely feel like a different writer after having written the book.

TMR

I think Homeland Elegies is a masterpiece, and I don’t use that word lightly, or often. I didn’t think that the autofiction was all that unusual, because I kind of cut my teeth on reading Henry Miller when I was a young writer, in Paris. And if you read Tropic of Capricorn, you think this guy’s just writing his life story, but then you read Tropic of Cancer and you realize, no no, he’s off the chain and you realize that he’s calling himself Henry Miller, but he’s doing whatever the fuck he wants to do. With Homeland Elegies, I felt that you set it up so that you can have the total freedom, but at the same time, you don’t stray so far into fantasy, as to forget a kind of political responsibility. When you talk about Salman Rushdie, or you talk about Trump, or you talk about Bork, or any of these things, there’s a landscape that is reliable from a historical and social viewpoint.

AKHTAR

Thank you for those comments, and I will try to forget them as we continue this interview, because I would be too humble to really to go on. I think that if there’s a subterranean core to the book, it’s the preoccupation with depicting the social construction of the self, that the way in which society and the individual, in this case, the narrator, are inextricably linked, and that the creation of the consciousness of this narrator is inextricably linked to the city to the society. You know, as Plato would say that the city is the metaphor for the soul. And so, if we talk about what’s happened to America and the disrepair that it’s come into, Trump is a kind of figurehead, and a symbol, if you will, of the city. If Trump is the manifest consequence of the city, then to the extent that Plato’s right that the city is the metaphor for the soul, what does that say about the American soul, if you will?

TMR

You have a character who is an agent in Hollywood, who happens to be a black American. And he warns this new kid on the block, this Muslim playwright who gets invited to come and write TV for film in Hollywood. They’re dining in a restaurant and he says, make sure that they know that you’re on their side. He’s talking about Hollywood players, and presumably, a lot of them are Jewish and pro-Israel. In response, your protagonist says something about he he grew up on Philip Roth and Arthur Miller, “you don’t have to worry about me.”

AKHTAR

He didn’t say exactly that. Hari Kunzru, in his review in the Times Book Review, wrote something about how this was a book written by a Muslim American, which is nakedly inspired by Philip Roth, in which the narrator’s relationships to the Jewish American experience are the source of conflict for his own relationship with his own community, who is denied at the end of the book a visa to go home to his parents homeland, because of a trip he had made to Israel. All of that is part and parcel of a larger question, which for me has been in my work almost from the beginning, which is accounting for the paradox that I grew up in a culture and in at least in a family that was at times very nakedly anti-semitic. And I differentiate anti-semitic from anti-Zionist; both things were true. And so how do you account for the fact that I found so much inspiration from — really the most inspiration from the Jewish American artists, whether they are Jewish American dramatic artists, or really comedians in a sense? How did this minority that lived for a time in a kind of existential tenuousness, forge something like a mainstream American voice, culturally? That phenomenon to me has been a fascinating one to study, explore, learn from all of that. All of that is part and parcel of that particular exchange that happens at the restaurant.

TMR

There are a couple of things at play here. In the novel you talk a lot about what happened on 9/11 — not a lot of the details of the attack itself, but the aftermath, and you also mentioned the assassination 10 years later of Osama bin Laden.

AKHTAR

I’m not in the business of problematizing the dominant understanding of what happened on 9/11. That’s not my fight. It’s clear to me that the cynicism with which 9/11 was used by those in power bespeaks a cynicism that is common, I think, to those who are in power. Who knows what really happened? To me, I am dealing with the facts of 9/11, as I experienced them, as I experienced them as a media event, as I experienced them in this city, living here.

The conspiracy theory part of 9/11 is an important part of my familial conversation, in the sense that a lot of folks who talk about what may have happened and who really is really responsible etc, I’ve never really gotten into it. For years after 9/11, I found that the conversation around all that was really about something else, it was about being disconnected from the power that was really making folks’ lives.

TMR

Do you feel that you can say and write anything that you would like to, without fear of offending Jews in Hollywood or Muslims in Mecca?

AKHTAR

Oh, I see. Great question. Um, I would like to think I am. But I certainly recognize with regards to the Muslim community that I have parsed, I have been careful at times, and I haven’t wanted to give a certain kind of offence, because I felt that it was going to be received as an act of malice, when in fact, it’s really an act of love. So, I think that it’s impossible to say that I’m completely free. But I don’t know that I’m completely free to write about the American experience either, in order to be heard. For the language to have purchase, it’s got to find that sweet spot of attack — you’ve got to draw a little bit of blood, but you can’t draw so much blood that the readers got to go off and get disinfected at the emergency room. You want to keep them in the experience. There’s that and those are all issues of craft and rhetoric, though ultimately that you are right to say that they do point to political perspective.

The artist I admire the most is Shakespeare, and he’s the one I learned the most from, the one I spend the most time reading. And I couldn’t tell you whether he’s pro Catholic or pro Protestant, whether he was pro Elizabeth or pro James, I can’t tell you if he’s pro landed gentry or he’s pro the common man. He’s all of those things at all of those times. And when he has to inhabit the consciousness of Henry the IV…politics is secondary to art in that respect, and to me it’s an issue of craft.

TMR

At the end of your novel, you write, “America is my home…This is where I’ve lived my whole life. For better, for worse—and it’s always a bit of both—I don’t want to be anywhere else.” Have you never considered living abroad, then?

AKHTAR

It would be as an exile. This is the this is my only home, you know.

TMR

Well, let’s talk about the exile just for a moment. Because it seems as if Americans cannot be exiles; we can be “expats,” but we can always come home. Thus, we’re not really in exile, because politically or economically, we’re not necessarily forced to leave like people from Lebanon or Syria or Afghanistan.

AKHTAR

I hear you, I mean, America is my home. But I don’t rule out anything.