The dispossession and ethnic cleansing happening in Gaza and soon perhaps, the West Bank, have stark historical precedents.

I have been a witness to and a participant in the Palestinian-Israeli “conflict” for over fifty-five years, since I was a teenager in Ramallah. I have been chronicling it in almost daily diary entries throughout that half-century. I’ve also played a part in resisting human rights violations and confiscations. And yet, perhaps the worst period in my experience has been the last sixteen months. It took the war on Gaza to make me realize how closely my world view was related to the prospective peace with Israel.

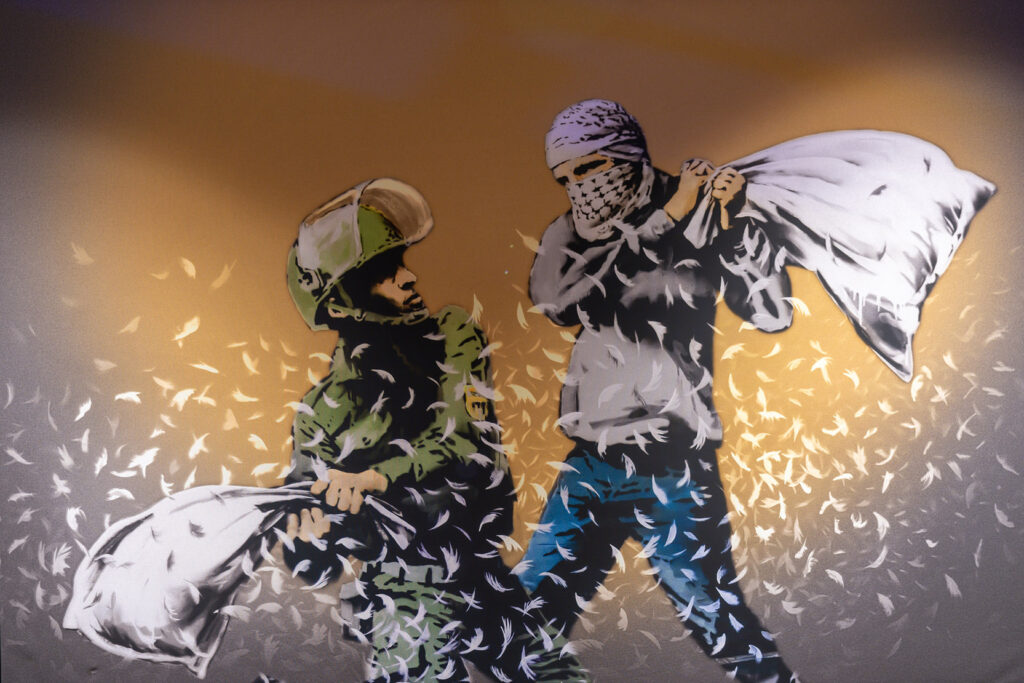

As the war went on, with its threat of unimaginable destruction, the thought on my mind was — after such knowledge, how can we live together? And yet we must. This simple four-word sentence explains why I’ve spent a lifetime thinking and writing about relations with Israel.

Beginning with Jaffa

Let me begin with Jaffa, the city where my parents lived and where my father had his law office. Following the establishment of Israel in May 1948, there was a tremendous amount of looting of Palestinian homes and properties after their residents were forced out. I now wonder whether my father knew, as he worked for the return of refugees from his exile in Ramallah, that five months after the city’s conquest, Jaffa had been picked clean; there was nothing left in Palestinian houses. I can just imagine him comforting his friends who came to him fretful of what might be happening to their homes, he with his eternal optimism telling them of his efforts and how close he and others were to victory and return.

From reading one of the letters that my father drafted to the UN Palestine Conciliation Commission, I know that he was concerned about the lack of watering of the citrus trees in the orchards surrounding Jaffa, which might otherwise not survive. Clearly he was not aware of the policy Israel was pursuing of ethnic cleansing of the Palestinians. I only discovered this letter after I finally came round to opening the cabinet that contained my father’s papers, which had remained closed for many years after his murder in 1984. The documents I found there formed the basis of my book, We Could Have Been Friends, My Father and I. Perhaps the reason for my delay in inspecting these files was that I was trying to forget the city of Jaffa that had loomed so strongly in my consciousness as I grew up.

When I was a child, we would look across the Ramallah hills at the lights in the horizon that we believed were the lights of Jaffa. It was only later, after 1967, when we were able to visit, that we realized they were in fact the lights of Tel Aviv. The British Jewish journalist Jon Kimche, who by the way met and befriended my father after the war of 1967, wrote that “the first people to loot in a wholesale fashion were members of the Irgun.” While in the beginning they looted dresses and “ornaments for their girlfriends… this discrimination was soon abandoned,” and they began to snatch anything they could transport out of the city: everything from furniture and carpets to pictures and housewares. “What could not be taken away was smashed. Windows, pianos, fittings, and lamps went in an orgy of destruction.”

The Israeli general staff used the Hebrew word tihur, meaning “cleaning” or purification, more than forty years before the concept of ethnic cleansing was coined at the time of the wars in the former Yugoslavia.

But not all the officers and leaders in Israel were of the same mind. From Adam Raz’s book Loot: How Israel Stole Palestinian Property, we learn that there were some conflicting voices regarding the looting. Some feared its effect on Jewish society and the image of the state; others were concerned about future relations with Arabs. They were right to be worried.

On July 4, 1948, Eliezer Bauer of Mapam asserted at a Histadrut executive committee meeting that “it is not a coincidence that this type of robbery and expulsion is taking place — there is an undeclared, yet highly effective, plan to make it so no Arabs will remain in the state of Israel. Therefore, robbery is not encouraged, but nothing is done to prevent it. Things are being done in such a way that the Arab’s economic foundation is being destroyed. If we declare that they can return, and if they want to return, they will neither have a place to live nor a way to make a living…”

No wonder then that my father worked around the clock to get UN resolution 194 for the return of the refugees implemented without delay as I describe in the book, We Could Have Been Friends, My Father and I. It is also clear, but perhaps not surprising, that Israel was not abiding by the capitulation agreement that promised residents of Jaffa that after they were identified they would be allowed to resume their lives.

Avraham Tamir, the deputy assistant chief of staff for operations in Central Command, who after the war was responsible for the destruction of many villages, explained that Prime Minister Ben-Gurion asserted the “policy that the villages needed to be destroyed, so that the refugees would not have a place to which to return.” He continued, “I mobilized all the Central Command’s engineering battalion, and I flattened all those villages within forty-eight hours. Period. There was nowhere to which to return.”

Does this remind the reader of Gaza?

Without a country of their own, the Palestinians were deemed disposable and stateless. They are not recognized as having memories and attachments to place, as we all saw in Gaza following October 7, 2023.

Common Denominators

There is a common denominators in Israel’s war, as noted by Daniel Dor in The Suppression of Guilt: The Media and the Reoccupation of the West Bank: “The foundational basis lies in the portrayal of Israel — its government, its military, its people — as an agent without intentions, an innocent society that has been pushed into the operation, just as it was pushed into the entire Intifada, by the sheer force of Palestinian violence, with no agenda of its own except self-defense. A desperate attempt to do something — whatever possible — against terror.”

He adds, “None of these commentators ever raises, or even hints at the possibility that Sharon [then the Prime Minister of Israel] actually knew very well what he is doing, that he does have a plan and that he is not particularly bothered by the fact that the military operation will not lead the parties back to the negotiating table.”

The plan came as a shock to me. I didn’t realize that my country was for sale.

Likewise, in the Gaza war, Israel portrayed itself as having been pushed into fighting, thereby neglecting all it had done to imprison the people of Gaza for the sixteen years that preceded the war. Another common thread that pervades these wars is the attempt at destroying the Interim Self-Government Accords agreed in Oslo in 1993-95, in order to prevent an independent Palestinian state. In 2002, there was General Meir Dagan’s plan, which “reflected Sharon’s world view, and which had two basic components: First, Arafat is a murderer and one does not negotiate with or do business with a murderer. Second the Oslo agreement is the greatest disaster visited on the people of Israel in modern times and thus no effort should be spared in undoing it… the plan is to cut off the Palestinian Authority into cantons, bits of territory isolated from each other, disconnected from any central government and handled individually by Israel” (quoted in The Suppression of Guilt: The Israeli Media and the Reoccupation of the West Bank, by Daniel Dor).

Again, does this remind the reader of words spoken during the Gaza war and the Israeli army and the settlers’ actions in the West Bank?

In the Gaza war, there is the General’s Plan, conceived by retired Major General and former head of the National Security Council, Giora Eiland, and presented to the Knesset by a group of several retired Israeli generals. This plan consisted of giving approximately 300,000 Palestinians a one-week evacuation period to depart from the northern third of Gaza before designating it a military exclusion zone; anyone remaining in the area would be considered a combatant. Next, the plan was to implement a complete siege that would block essential supplies, including medicine, fuel, food, and water, until militants surrendered — a radical shift in Israeli military strategy for northern Gaza.

It is clear from what we have seen happen in Gaza that the Israeli army was pursuing this plan without formally announcing that it was adhering to it. Yet the Gazans knew. Atef Abu Saif writes in his war diary from Khan Yunis, Don’t Look Left, in the entry for November 9, two months after the start of the war:

The Israeli army always knew what the mission was: ethnic cleansing of the whole Strip; when they enter a neighborhood they’re not going to say ‘OK, who voted for Hamas in 2006’ or ‘Who’s likely to vote for them in the future?’ and then just ‘cleanse’ them. It’s not Hamas they’re clearing. It’s Arabs. When they see you, they will either kill you or force you to leave, whichever is quicker. You have no choice: either you die or you leave. You cannot say that you want to stay peacefully and promise not to trouble the occupiers. Many don’t even get to choose — the missile just finds them.

The “day after”

On February 6, 2025, President Donald Trump signed an executive order that authorized aggressive economic sanctions against the International Criminal Court and its chief prosecutor Karim Khan, accusing the latter of taking “illegitimate and baseless actions” targeting the US and Israel.” Surely the wholesale destruction of Gaza buildings had no essential military necessity but served another undeclared agenda of making Gaza uninhabitable so that it is eventually emptied of its people. Some might think that the ceasefire brokered on January 19 and withdrawals from Netzarim checkpoint would mark the end of the General’s Plan. And yet, as long as the siege of Gaza by Israel is maintained, Netanyahu knows that he holds the key to enforcing his plan through preventing the importation of shelters for the people of Gaza, as well as of drilling equipment, earth-moving equipment, and asphalt to enable the reconstruction to begin. A ban on building materials entering the Gaza Strip has been a feature of Israel’s blockade since it was put in place in 2007.

Rather than making life tolerable for civilians who found their homes destroyed, Trump proposed what amounts to ethnic cleansing of the Gaza Strip. Under his scheme, Gaza’s 2.2 million Palestinians would be resettled and the United States would take control and ownership of the coastal territory, redeveloping it into the “Riviera of the Middle East.”

The plan came as a shock to me. I didn’t realize that my country was for sale.

Meanwhile, in the West Bank, under the guise of the Gaza war, military operations continued with the aim of destroying the troubled Palestinian Authority and the resistance. Thus, October 7 and the war in Gaza marked the definitive failure of the Oslo Accords. Far from laying the groundwork for a lasting peace and the coexistence of two independent states, the accords were sabotaged from the start by Israel, which used them as a basis for settling the West Bank, annexing eastern Jerusalem, and isolating the Palestinian Authority.

The U.S., European allies, Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, and other countries all expressed their interest in working with Israel on a “day after” plan that would allow the growth of an alternative Palestinian government. But Netanyahu realized early on that such a government would have to include, to some degree, the Palestinian Authority, and that this would be a red line for his far-right coalition allies, on whom he relies to hold power. Having to choose between the implementation of the war’s stated goals or the preservation of his coalition, he chose the latter.

There was another similarity between the earlier period and the present in the Israeli response to the ICJ.

In 2004, the International Court of Justice at the Hague heard a case against the construction of the wall in the Occupied West Bank, in which I participated. The Court concluded that the wall as it stood was illegal. What was striking in the Israeli public’s reaction to this advisory opinion was the utter sense of guiltlessness. One typical reaction was by a woman who responded, “You sit in judgment while I bury my husband.”

Likewise, when the International Court of Justice at the Hague in 2024 concluded that there was a probable case of genocide, Israel again claimed that there was anti-Semitism and bias against Israel. “Israel utterly rejects the false and absurd charges of the international criminal court, a biased and discriminatory political body,” the Netanyahu office said in a statement, adding that “no war is more just than the war Israel has been waging in Gaza.”

There are a few avenues for peace albeit slim.

Dahlia Scheindlin, an Israeli expert on international public opinion, had this to say: “It will strengthen Netanyahu. Israelis are absolutely rock-solid convinced that the international system in general basically exists in order to target and single out Israel unfairly. That kind of sentiment cuts across the board in the Jewish community.”

As Pankaj Mishra wrote in The World After Gaza, Yeshayahu Leibovitch had warned of this as early as 1967 when he wrote, “the tactic of conflating Palestinians with Nazis and shouting that another Shoah is imminent was [he feared] liberating ordinary Israelis from ‘any moral restrictions, since one who is in danger of annihilation sees himself exempted from any moral considerations which might restrict his efforts to save himself.’”

At present, Israel is employing the same tactics in the West Bank that it used with total impunity in Gaza. These include orders to leave neighborhoods, destruction of infrastructure, demolitions of homes, and killings. The intention is to destroy any chance of peace and a Palestinian state. Again, nothing new. As in 2002, when Israel destroyed the Old City of Jenin, it is now destroying the Nur Shams camp in Tulkarim, Tubas, and other villages in the north of the West Bank. Tens of thousands of inhabitants living there were forced to leave their homes, some of which have been blown up Gaza style. The infrastructure has been destroyed. Drones and warplanes have taken part in these attacks. It has been suggested that these army raids are in order to assure the right wing that, despite the ceasefire agreement, the war has not stopped.

Israel claims it is fighting terror in the Jenin camps, but it also closes West Bank roads causing havoc to the economy. It should be noted that Israel is borrowing tactics used by the British in 1936 in Jaffa’s old city to fight the resistance, including demolishing homes to create wider roads in the form of a cross to enable military vehicles to pass more easily. Israel also uses administrative detention and expulsions, methods also inherited from the British Mandate era as punishments of those accused of helping the resistance.

As I have argued in What Does Israel Fear From Palestine?, it is Palestine’s very existence that Israel fears and tries to prevent. My conclusion in that short book was that “should Israel not accept a fully sovereign Palestinian state living in peace side by side with it, the alternative is that Israel would be transformed into an openly fascist, racist state that has to go from war to war.” At the time I wrote those words, the Israeli police was holding the proprietor of the main East Jerusalem bookstore in custody, accusing him of disturbing the public order by selling books after seizing some 30 books, including a children’s coloring book titled, From the River to the Sea, by South African illustrator Nahi Ngubane. Selling books in Israel has now been deemed a crime.

Let me put it another way — how can Palestinians live with Israelis after all that has happened since October 7? There are a few avenues for peace, albeit slim ones. Wars usually bring in their wake massive, sometimes unexpected changes. And Gaza has, in many ways, been a game-changer for Israel. Israel’s reputation has been badly damaged, there are ICC cases against its leaders, and the global backlash has pushed the Palestinians higher on the international agenda than ever before. There is also a new generation of world citizens who believe that the Palestinians should be free. Even Trump’s disguised calls for ethnic cleansing in itself highlight Israel’s crime.

And yet, in response to the question I raised at the beginning of this essay — how can we live together? — I will give the same response: And yet we must. As David Shulman, a longtime activist for peace between Israelis and Palestinians, wrote in the New York Review of Books, “These days the uncontested rulers of the West Bank are the marauding Israeli settlers in the illegal outposts that are popping up everywhere. Their express goal is a second Nakba — the expulsion of the entire Palestinian population in Area C, some 62 percent of the West Bank over which Israel has sole control.” He also wrote, “Empathy is usually focused on individuals, not on groups. But still: believe it or not, the Palestinians are our sisters and brothers, and someday, if the Israeli state survives, they will be our partners in making peace. There is no other way forward.”

It goes without saying that not all Israelis feel this way. There are dissenting voices in Israel who care about the loss of Palestinian lives.

A dear Israeli friend wrote to me on September 30, 2024, “Tomorrow is Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement. I thought you might like to see something my niece sent me — powerful and beautiful, commemorating, mourning and praying, on Yom Kippur, for Palestinian lives lost in Gaza.”

Let’s hold on to these sparks of hope and not resort to despair.

This essay was adapted from a lecture given at the Bruno Kreisky Forum for International Dialogue in Vienna, Austria, on March 10, 2025.

![Fady Joudah’s <em>[…]</em> Dares Us to Listen to Palestinian Words—and Silences](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/SAMAH-SHIHADI-DAIR-AL-QASSI-charcoal-on-paper-100x60-cm-2023-courtesy-Tabari-Artspace-300x180.jpg)