Select Other Languages French.

What role does justice — as distinct from law — play in a world where the main and clear culprits appear to yet again roam free?

I have Palestinian friends who wake each morning in tears. Others find their sleep colonized by nightmares. It is Gaza. The conversation is scarcely different with friends from Lebanon’s south, from Syria, from Sudan, from elsewhere, from the multitudes who have borne witness to destruction and slaughter.

Does the culprits’ escape from accountability, as so often happens, lock the wounded into a permanent state of emotional siege? The guilty no less than their victims, if guilt in them ever took hold. I sat in a long silence when I first read Myrtle Meadlo’s words to Seymour Hersh, in 1969. She uttered them the moment he stepped into her house in New Goshen, Indiana. He had travelled there to talk to her son, Paul, as part of his investigation into the My Lai massacre in Vietnam: “I sent them a good boy, and they made him a murderer.”

It’s almost always silence, isn’t it, that is the emotional register upon encountering the structure and grain of the human toll — torment’s inheritance. For me, at random: A Minor Detail by Adania Shibli; Fugitive Pieces by Anne Michaels; Put It On Record, I am An Arab by Mahmoud Darwish; Christ Stopped At Eboli by Carlo Levi; 3 Faces by Jaafar Panahi, Men In The Sun by Ghassan Kanafani, A Map To A Place That No Longer Exists by Abdallah Hani Daher, The Ministry Of Utmost Happiness by Arundhati Roy… They sit well, these, and others, in the mind’s lens and the heart’s rhythms.

But is justice one of the rewards of the intimate human tale, as told through brush, camera, and pen, quite apart from the realm of law and its reach? I ask because ours is a growing fear that today’s culprits, like yesterday’s, shall yet again roam free. It was not so long ago that scores were let go even as Nuremberg put some in the dock.

Look at them now. In the shadow of genocide, killing daily in Gaza, ethnic cleansing in the West Bank, scorching the earth in south Lebanon, swaggering in Israel. Look at them looting the land, massacring, torturing, hounding, in Sudan. Look at them gunning down protestors by the thousands, maiming, raping, in Iran.

Too many names, too many times in history, in too many places, I know. These are merely the ones within my own line of sight. The crimes differ by degree, by type of horror, by tally, by intent. What difference does that make, though, for offender and victim outside the law books?

Philip Sands is a leading attorney and scholar in the human rights field. He commands the page, much as he does the courtroom. It is literature, not law, that holds the better promise, for him, of offering a modicum of solace and redemption:

If I had to choose between a single judgment in an international court on some horror that has happened or a very fine work of literature addressing that issue, I would probably choose the work of literature, because it is more likely to bring peace and reconciliation.

I sense his compassion in such counsel. It is as if he is gently warning the maligned and the aggrieved that law, even when it is victorious, may disappoint. It often does. Accountability, even in the tidiest of convictions, proves elusive, and is just as often unenforceable in cases of war crimes. In the present era, it may even turn perilous for the judge courageous enough to issue it.

So, too, is the word’s power to its author. Count the condemned writers and artists crowding prisons and detention centers, languishing in exile, joining the ranks of the cancelled, the silenced, the unemployed. Ours are not the kindest of times anywhere. For the elites, they are certainly at their most glaringly debased.

Might catharsis, that essential cleansing capable of yielding collective peace and reconciliation, be achieved without the law’s ubiquitous redress? The truths it casts in stone-like verdicts, the facts it declares incontrovertible, notwithstanding humanity’s proclivity for interpretation, and the reckoning it therefore imposes.

“Fine literature,” by its nature, is the privilege of the reader. Even at its most famous, it almost always stands modestly, in fragments of prose and passages. Film, as mass theatre, has the gift of reach but can it equal the law’s gavel when it falls for the victim? Can it negate it if it falls for the accused? And if the gavel fails to fall at all, might that work of fiction, this poem, that film, those images — might they earn a people recognition for their persecution and anguish? Might it earn the culprit their guilt, their mea culpa, and their shame?

And I have a confession: at times, our real-life tragedies overwhelm me to the point that I am incapable of bearing witness to them on any other stage. I know that I am not alone in such sentiments.

But perhaps Sands has a point. A persuasive one. We have known, since the earliest days of the Palestinian–Israeli struggle over Palestine, that narrative matters. We are seeing it again today, in the aftermath of October 7, as the balance of that narrative pivots and Israel fights to reclaim it, no less urgently than it seeks to keep itself and its leaders outside the jurisdiction of international law. Modern history offers no shortage of instruction: Adenauer’s postwar Germany recasting Nazism as a regime’s malaise from which the people were innocent; colonial powers rehearsing deflection instead of apology or reparation; museums raised for some victims, withheld from others — all for the sake of narrative.

I notice as I write, that this argument reads like a polemical pileup. I don’t mean it to be so. The truth is I am barely scratching the surface of an unbearably thorny moral landscape.

On Another Note

I am staying on subject this week to share an extraordinarily fluent essay by Peter Harling in Le Monde Diplomatique, “Gaza, signe des temps : Faire le vide,” on precisely the theme of this column. He writes:

By proclaiming the end of the conflict, they appear to resolve a whole range of thorny issues — presumptions of genocide, accusations of complicity, abuses of international law — simply by consigning them to the past. The war our governments wanted to treat as a parenthesis can finally be closed.

This arbitrary closure plunges into disarray all those who saw in this conflict, on the contrary, a turning point: a monstrous, uninhibited violence, heralding a world without faith or law, governed solely by racist impulses backed by overwhelming technology. But if everything ends in contagious indifference, then what really happened? Can a war be both so grave and so quickly forgotten? How can one avoid the sense of unreality, like waking from a nightmare that was horrifyingly tangible and yet without sequel? Around what should one mobilize, when a relative de‑escalation of violence meets a growing emotional and moral exhaustion?

If you are a subscriber to Le Monde Diplomatique, click here for the essay. If not, please email me to gift you the piece.

Amal Ghandour’s biweekly column, “This Arab Life,” appears in The Markaz Review every other Friday, as well as in her Substack, and is syndicated in Arabic in Al Quds Al Arabi.

Opinions published in The Markaz Review reflect the perspective of their authors and do not necessarily represent TMR.

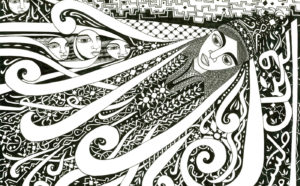

FROM THE ARTIST: Tom Young is a painter living between Beirut and London. About “Double Standard,” he writes that the painting was “an attempt to respond creatively to the ongoing nightmare in Gaza, Palestine and South Lebanon; to portray desperate inequality in the world, huge profits made by the few from the unimaginable suffering and pain of others. The inability to recognize the humanity of the ‘other,’ the inability to see we are all connected.

It’s the most disturbing and distressing situation of my lifetime. If we look away, unable to change anything, we can be complicit in our silence. If we look closer and try to help, it’s easy to become immobilized by trauma and unable to function in our everyday lives. If we criticize the ongoing massacres and policy of ethnic cleansing, we are labelled antisemitic and supporters of terrorism. How did we come to this?”

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)