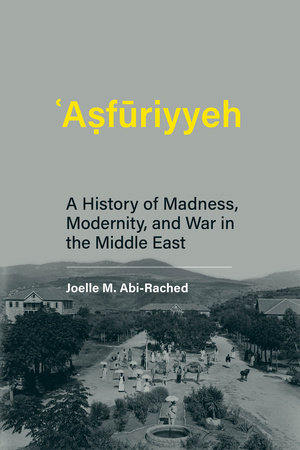

Joelle M. Abi-Rached reflects on the failures of psychiatry and psychiatric language in addressing the trauma arising from mass violence.

I must have been eighteen or nineteen when I first saw a production of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot in Beirut. I remember very little about the play save for one moment: when Vladimir takes a pistol from his pocket and pulls the trigger. The round was of course a blank. But the shot startled me, and I immediately left the theatre. Interestingly, I wasn’t the only one; others followed.

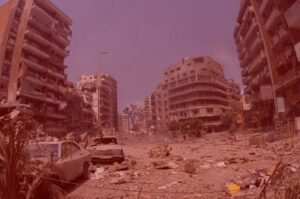

Another common trigger in our part of the world is the sonic boom of Israeli warplanes. As long as I can remember, they have been part of our daily lives. When I first went to London in 2006 — after leaving Lebanon under catastrophic circumstances during Israel’s war with Hezbollah — it took me several months to rid my ears of the constant buzzing sound of warplanes. My friends would laugh whenever I looked up at the sky in anguish. It took me months, if not years, to tame my fear of the sky. And to be honest, I’m not sure I’ve ever fully overcome it. This became painfully clear after the heavy bombardment of Beirut in September 2024, at the resumption of Israel’s unfinished war with Hezbollah. I was consumed by panic and dread.

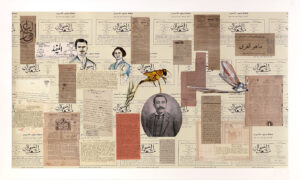

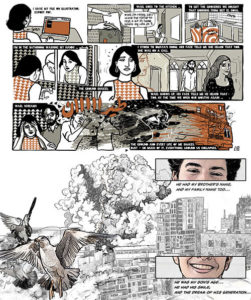

Like many Lebanese, I carry psychological scars that are deep, multilayered, unresolved, and often unspoken. They sediment and pile up from crisis to crisis, through political upheavals, wars, and other plagues. Some are personal, and others collective. Some lie in the past; others are still unfolding. Some endure through intergenerational stories; others I have experienced firsthand. Some I have learned through encounters with survivors or descendants of survivors, and others through documentaries and history books. Together, they mark the blows endured and the residue we live with.

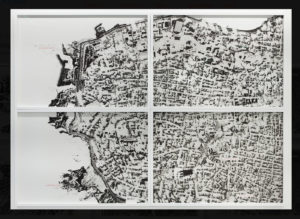

It took me years to distinguish between “rational” and “irrational” emotions — the ones I could not control, the ones that would erupt every time I returned to Lebanon and faced new, disturbing violations of what “normal” means. Alongside anxiety and some iteration of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder — two pervasive ailments the Lebanese suffer from[1] — I also developed claustrophobia (fear of enclosed spaces) and agoraphobia (fear of crowds or assemblies). The former has always been more paralyzing than the latter, and I know exactly why. It goes back to a traumatic memory endured in the stairwell of our building. Stairwells, or daraj (Arabic plural “for stairs”) are places very familiar to the Lebanese, who have often taken refuge in this dreaded “non-space” — to borrow Marc Augé’s concept — during wars and periods of civil unrest, since the vast majority of the population does not have the luxury of underground shelters. I must have been eight. This time, it wasn’t Israel but the different Lebanese factions shelling us during the accurately named “War of Elimination” (Harb al-Ilgha’). I was certain we would die. Bombs hailed down, as our neighbors, my sister, and my grandparents huddled in the dark of our shaking building, lit only by candlelight. I don’t remember how, why or even how long this ordeal lasted. What I do remember is my parents returning weeks later — after months being stranded away from us by mined roads — and promptly packing up our things. The following day we left for Cyprus by boat, only to return after the official end of the civil war in 1990. We never spoke of that period. We never processed it. Life simply continued.

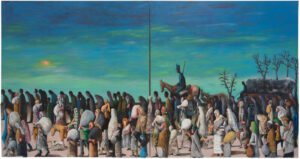

I share these memories — a broad sketch of the topohistory of my traumas — because they have twice resurfaced with a vengeance in the past two years. The first was during Viet Thanh Nguyen’s Norton Lectures at Harvard in 2023, in which he spoke about how he and his parents came by boat from Vietnam to America. While I was listening from the upper floor of the magnificent Annenberg Hall, it occurred to me for the first time that we, too, had been refugees, though we had never articulated our ordeal as such. Perhaps this is because, as Hannah Arendt put it so well, “in the first place, we don’t like to be called refugees.” The second moment came after Hamas’ attacks on neighboring kibbutzim on October 7, 2023. Given what I know about the region’s history, it was clear to me that the gates of hell had been opened. What was different this time, however, was that I saw myself in those Palestinian children being slaughtered: helpless, treated like “human animals,” to use the words of Israeli Defense Minister Yoav Gallant.

A psychoanalyst would say that this identification with the children in particular is a form of regression (being reminded of and slipping back into an earlier stage of helplessness). But I believe it is because, for the first time in a long while, I felt deeply shaken by the overt double standards of academics and institutions — their euphemisms, their silence, their refusal to name what they saw. I witnessed racism among otherwise well-meaning people and watched dehumanization being excused. What shattered was my stubborn — perhaps naïve — faith in progress and in a universal humanism into which I could dissolve my identity. After all, genocide advances through the dehumanization of the other, and silence abets it. I see now that I had been an idealist malgré moi: skeptical of triumphalist progress and messianic histories yet still believing we could champion a just world under a universal human-rights framework.

The slaughter we have witnessed — and are still witnessing — in Gaza, the killing of poets, teachers, parents, children, healthcare workers, the annihilation of an entire society within a tightly controlled area with no escape — was, for me, a warning of what could one day happen to us all. Somehow, like Viet Thanh Nguyen, who, confronted with Trump’s policies of separating immigrant families, had been made to relive the memories of his own family’s displacement as refugees from Vietnam, Gaza made me realize two things. First, that I have never truly opened up about my own scars, which I have preferred to bury under an ethic of denial; and second, that, as written in the Book of Ecclesiastes, there is, alas, nothing new under the sun. All we who lack real power can do is witness and write what endures in human nature: its contradictions and its dualities.

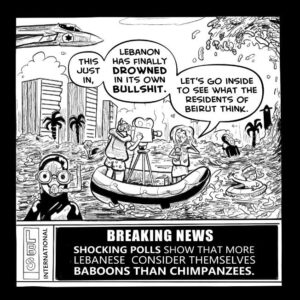

Well before UNRWA characterized the overwhelming trauma experienced in Gaza as “chronic and unrelenting,” observing that it “defies traditional biomedical definitions of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), given that there is no ‘post’ in Gaza’s context,” numerous professionals, including Samah Jabr, had already articulated this point. Jabr, a Jerusalem-based psychiatrist who navigates both Palestinian and Israeli discourses, told me she has long wrestled with practicing in a society that often denies Palestinian suffering. She noted the “cognitive dissonance” of some Israeli colleagues, who overlook the psychological needs of Palestinians living under oppression, and she knows that psychiatry’s tendency to pathologize behavior is especially problematic in an oppressor–oppressed colonial context — a point central to Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth. In her Edward Said lecture at Princeton University in February 2024, Jabr sarcastically remarked how her profession was “not the most progressive.” And how psychiatry has been complicit throughout history in pathologizing dissent and rebellion, in effect aligning itself with regimes of power and structures of violence, exactly as Fanon wrote about. She gave the example of the Russian regime’s invention of a new diagnosis, “sluggish schizophrenia” — a diagnosis never validated or approved by mainstream psychiatry — for the purpose of silencing dissent and political opponents. She also mentioned how Ayelet Shmuel, an Israeli social worker and psychoanalyst who heads an International Resilience Center in Sderot, called Gazans “sociopaths” who should be held “accountable” for their “indoctrination,” contrasting them with “psychopaths,” whom she considered irremediable because they were “born that way.”

Jabr could have reminded her audience that this is exactly how racist white supremacists described Black Americans. In the nineteenth century, enslaved people who resisted were pathologized as “mentally ill”; “drapetomania” was even invented as a diagnosis to label that “condition.” Blackness itself was medicalized as a defect. Early “alienist” writing cast Blacks as closer to animals and the sexually criminal. Nineteenth to early twentieth-century Southern medical journals claimed a “preponderance of animal organs over intellectual and moral organs” in Blacks and published pieces like “The cause and prevention of rape-sadism in the Negro” and “Sex crimes among the Southern Negroes; scientifically considered.” This medicalized a stereotype of Black “brutishness” and criminality. During the civil rights movement, Black protestors and activists were described as suffering from a form of psychosis. The psychiatrist Jonathan Metzl has shown how the image of schizophrenia shifted from a largely white and innocuous disorder to an allegedly dangerous, paranoid, predominantly Black male condition. How familiar these racist and dehumanizing thoughts are, alas.

This is not to deny the reality of mental suffering and mental illness, of course. Those who depend on antipsychotics to manage their symptoms, who rely on lithium to reduce suicide risk, and those who need antidepressants to keep living despite immense hurdles, not to mention those who suffer from epilepsy, are among the most neglected amid the medication shortages in Gaza. They deserve access and support. Their suffering is real. And yet, what does it mean to “reduce the risk of suicide” in a setting where children say they would rather die than live? And, as Samah Jabr highlights, what does it mean to talk about mental-health support in a context where people are hungry and starving? Indeed, what does it mean to call for more mental-health tools and psychosocial support when the very possibility of psychological well-being is being erased and the conditions for mental health are being obliterated? Jabr and her co-author, American psychiatrist Elizabeth Berger, speak of an “occupied state of mind” in Palestine. I think there is more to it. There is, borrowing a Lacanian term, what we might call “psychic foreclosure,” which is the erasure of the conditions (including symbolic ones) necessary for mental health, foreclosing the possibility of psychic well-being entirely.

This “psychic foreclosure” also applies to those who lost loved ones in the Beirut port explosion of August 4, 2020, which killed more than 217 people, wounded more than 6,000 people, and devastated substantial parts of the city. I was struck by how the parents of Krystel El-Adem, a victim of the blast, recently expressed their unrelenting despair and grief, five years on from their daughter’s death. They said they lost their will to live that day. Time had stopped. The only thing they looked forward to was getting closer to their daughter as the days passed. Krystel’s father was unequivocal: closure is impossible without justice. Had they sought psychiatric care, they would have doubtless been diagnosed with “Prolonged Grief Disorder” (PGD), a grief response that stays intense and disabling far longer than is typical for “the person’s culture.” In DSM-5-TR, PGD may be diagnosed in adults more than 12 months after a loss when there is persistent yearning for or preoccupation with the deceased, along with several symptoms that impair daily functioning. But how can one ever truly overcome such grief? What is “typical grief” in a country like Lebanon, “a land of aching hearts,” to borrow the title of Leila Tarazi Fawaz’s book? What is “typical grief” in Gaza? Aren’t Greek tragedies, in a sense, meditations on PGD? The culture and politics of “speed,” as Paul Virilio called it, the culture of efficiency, productivity, and transparency that we inhabit, is eager to declare PGD over and done. Cultures that reflect, even cathartically, on what it means to be human do not demand that grief end. Yet endless grief stands as an obstacle to an economy that depends on resilience, continuous growth, indeed “post-traumatic growth,” and the normalization of violence.

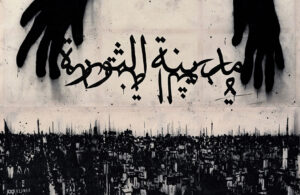

In a recent essay for The New Yorker, the journalist Mohammed R. Mhawish wrote that “in Gaza, therapy has become a language of holding on.” I would rather say that language itself has become a therapy of holding on, the language of chronicling, of expressing support, of listening, of caring, of denouncing, and calling out. Not therapeutic jargon per se, but a language that names ongoing crimes as clearly as possible; that speaks out and refuses to remain silent; that humanizes the “other” rather than tacitly or openly endorsing dehumanizing — or even pathologizing, language. The language of therapy is, after all, at best reductionist and, at times, historically dangerous. As many therapists would tell you, acknowledging crimes, violence, and the trauma they cause is the first step in therapy. For Palestinians, too, a recognition of their suffering is a form of therapy, a reassurance that their dignity endures despite the “Palestinian question” being liquidated in front of our very eyes. Some, like Samah Jabr, would even argue that what is needed is not therapy per se but support, “because people have been wronged.” Indeed, in the face of injustice, therapy is merely “palliative care” to again quote Jabr.

In Trauma and Recovery, American psychiatrist Judith Herman argues that trauma is an “affliction of the powerless” and that studying psychological trauma is inherently political because it draws attention to the experience of oppressed people. She is right. However useful biologizing can be (in providing certainty, less stigma, access), trauma is no heart disease; it is fundamentally relational, contextual, and political. The British psychiatrist Derek Summerfield was among the first to criticize PTSD as ahistorical, hegemonic, inadequate, and decontextualized. In this tradition, often called “radical” or “critical” psychiatry — which includes psychiatrists like Fanon and Summerfield — Jabr also criticizes the individualism of mainstream psychiatry, labelling it as “hegemonic psychiatry,” a discourse, which she deems profoundly inadequate for addressing historical injustice. Nevertheless, I think that even critical psychiatry has reached an impasse as it confronts the moral abyss in Gaza today, having exhausted its conceptual and technical resources. As such, perhaps only a language and approach grounded in justice can begin to address the psychological toll of such violence on victims, perpetrators and witnesses alike.

James Baldwin described the United States in 1962 as a “spiritual wasteland.” He argued that white Americans needed spiritual liberation, something achievable only by liberating and embracing Black Americans. Toward the end of his essay “Down at the Cross,” Baldwin warns that failing to do so will lead the country to ruin. I hear something similar in the slogan “Palestine will set us free,” chanted in many protests around the world: Palestine has become a symbol that exposes the paroxysms of hypocrisy and the language of double standards that defines today the Western liberal order as well as the reductionist vocabulary that pathologizes the other within a moral and spiritual wasteland. “Trauma after Gaza” may mean, precisely then, the work of freeing ourselves from our own mental shackles.

[1] A nationally representative phone survey of 1,000 Lebanese adults (July–September 2022, published 2025) found 43.5% screened positive for probable PTSD, and “a substantial 62.8% of participants screened positive for any disorder (PTSD, Anxiety, or Depression) while 28.10% screened positive for all three disorders,” see: Josleen Al Barathie and Elie G. Karam, “Exploratory Factor Analysis of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5: Investigating Post Traumatic Stress Disorder Interconnected Dynamics with Depression and Anxiety in the Aftermath of Multiple Collective Stressors,” PLOS ONE 20, no. 5 (2025): e0323422.

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)