Select Other Languages French.

The Nasser brothers’ cinema, especially in "Once Upon a Time in Gaza," documents daily life in Gaza. Through their portrayal of this life, they convey the resilience of a people who persist despite adversity, highlighting their efforts to survive, even when it involves theft, trafficking, or corruption.

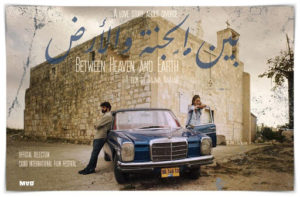

The new feature film by Gaza-raised filmmakers Tarzan and Arab Nasser is another take on their homeland, following Gaza, Mon Amour in 2021. Once Upon a Time in Gaza screened at this year’s Cannes Film Festival, where it picked up the Directors’ Prize in “Un Certain Regard.” It opens with images of bombing raids on Gaza, a trailer for what is supposed to be the first action film shot in Gaza, followed by a voiceover of Donald Trump giving his speech on February 5, 2025, in which he expresses his surreal plan to empty the Gaza Strip of its inhabitants and turn it into a “Riviera.”

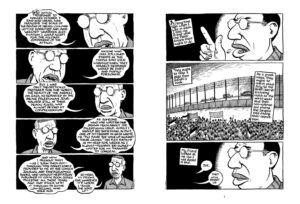

The collision between all these images plunges us both into a confusion between fiction and reality — which is the question that arises throughout the film — and the uninterrupted fury of daily life in Gaza. When we hear about Gaza, a whole imaginary emerges, carrying with it clichés, preconceptions and ideologies, no matter how little we know about life in the Palestinian enclave.

This phantasmagoria is accompanied by a flood of violent television and social media images, of destruction, war, bombardments, wounded families and children, refugees, food aid nowhere to be found — a media profusion that has increased tenfold in the almost two years of a total war to annihilate everything that is alive in Gaza. We are hyper aware of this reality, despite the fact that Israel forbids any presence of international journalists in Gaza, while it surgically targets Palestinian journalists reporting for Al Jazeera and other outlets such as the Guardian, Reuters and AFP, outlets that are hungry for the latest news and images, in spite of Israel’s embargo.

This is not what Once Upon a Time in Gaza shows us.

When the story begins after the prologue, we are immediately plunged into the codes of fiction, both in the settings, the treatment of the image, the characterization of the characters, the camera movements, and in the script, which develops a straightforward police plot.

In fact, against all odds, this turns out to be a “normal” film, despite the unspeakable drama unfolding in the Gaza Strip. Brothers Tarzan and Arab Nasser have chosen to make a film that avoids political discourse, and is even entertaining, which is unexpected when one is aware of Gaza’s daily horror stories.

Osama (an impressive Majd Eid, the physical alter ego of the Nasser brothers) plays a charismatic, resourceful cab driver who has organized a small-scale business selling drugs hidden in falafels. He’s the rogue with a big heart, who has taken under his wing as a partner Yahya (Nader Abd Alhay), a shy student who works in the sandwich shop.

Separated from his mother and sister in the West Bank, Yahya suffers from the prohibitions Israel imposes on Gazans. Yahya is the plot’s good guy to Osama’s villain.

The bully here is played by the excellent and demonic Ramzi Maqdasi, as Abu Sami, a corrupt cop in Osama’s illicit business venture.

But when Yahya denounces their deal, their complicity turns into deadly rivalry.

What follows is a story as much inspired by Sergio Leone (the title, the contemporary Western feel) as by an American thriller.

Halfway through the film, Yahya is cast as a Palestinian hero in a Hamas propaganda film. He gains in confidence, identifies with his character and, off-camera, takes the symbolic place of his departed mentor. In this twist, it’s reminiscent of William Friedkin’s To Live And Die in LA (1987), in the transfer of identification between two characters, the weaker taking on the role of the more charismatic. In terms of form, Once Upon a Time in Gaza is a film that delivers on all its genre promises.

With respect to content, everything the story shows and tells is determined by the (geo)political situation of the Palestinian territory: economic difficulties, survival, corruption (which does not depend solely on Israel, of course), violence, confinement, etc. It is no coincidence that the Nasser brothers set the film in the year 2007. It was a pivotal year for Gaza, just after Hamas’s legislative victory and the beginning of the asphyxiation caused by the Hebrew state’s blockade.

This is the film’s backdrop, its background noise, which we could almost manage to forget in the frenzy of everyday life, were it not for the distant shots of Israeli bombardments that punctuate the film and bring us back to the terrible reality.

In this, the film also has documentary value.

Ever since their first feature film Dégradé, ten years ago, set exclusively in a hairdressing salon, Arab and Tarzan Nasser, twin brothers born in Gaza, have been making films that avoid dealing directly with political hot-button issues, focusing instead on thoughtful camera work and plot development. In Gaza, Mon Amour, they recounted the love story of two sexagenarians, played by Hiam Abbass and Salim Daw, without the context of war to influence the viewer’s emotions.

What the Nasser brothers’ cinema undertakes, in Once Upon a Time in Gaza in particular, is the chronicle of daily life in Gaza, and through the very description of this life, they deliver to the world the testimony of a people who stubbornly refuse to die, who find the resources for their survival, even if it depends on theft, trafficking or corruption.

The filmmakers never give in to complacency or idealization. They paint a raw, frank portrait of more or less endearing characters struggling with a reality over which they have no control. “In Gaza,” Tarzan Nasser says in the film’s press notes, “a person’s identity is shaped not only by personal choices, but to a large extent by external conditions that limit those choices.”

In my view, what makes this film stand out is the international context in which it was released. No doubt this was a factor for the Cannes judges, who awarded the Nasser brothers the directing prize. While it’s true that the Cannes Film Festival is open to genre films (Titane by Julia Ducourneau, Palme d’Or 2021; The Substance by Coralie Fargeat, Prix du Scénario in 2024), historically, Cannes has always favored auteurs. And one could easily venture that something has radically changed in the international situation since the Nasser brothers’ last film. There was the horror of October 7, 2023, and the shockwave that followed and continues to this day. The war and the blockade turned into a desire to annihilate the Gaza Strip, to put an end to the Palestinian question.

And yet, even living in exile between Jordan and France, Arab and Tarzan Nasser continue to film daily life in Gaza through deeply human and moving trajectories, describing with documentary care the details that bear witness to what Gaza is really like (a pack of cigarettes, a newspaper wrapping a falafel, a pharmacy, a cab ride…). As if fiction freed the Nassers from political and journalistic discourse, they say in their gloss on the film, “We live in an age defined by images, where visual media have become one of the most powerful tools for influencing and shaping narratives. With cinema, we want to reclaim our own narrative.”

These Palestinian filmmakers in exile stubbornly continue to focus on remembering and capturing life in its daily details, as if everything in Palestine were doomed to disappear, as if another Nakba is here.

As the filmmakers explain together: “Through our films, we release a deep nostalgia mixed with desire, constantly trying to bring Gaza back to life. We’re not just making a film, we’re creating a veritable cinematographic archive of Gaza. A Gaza that the world tires of seeing reduced to news flashes or documentaries, whereas for us, it’s a full, vibrant life that deserves to be told and preserved through the language of cinema.”

Although the plot twists here would suggest Once Upon a Time in Gaza is a rather typical crime story, for this reviewer it is in fact an auteur film, despite its genre and style. To produce this kind of film today when talking about Gaza reveals a deep artistic commitment to craft. Only artists are capable of presenting their vision as a counterweight to the violence of reality.

Perhaps, paradoxically, the quality of Tarzan and Arab Nasser lies in their stubborn determination to make “entertainment” cinema.

![Fady Joudah’s <em>[…]</em> Dares Us to Listen to Palestinian Words—and Silences](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/SAMAH-SHIHADI-DAIR-AL-QASSI-charcoal-on-paper-100x60-cm-2023-courtesy-Tabari-Artspace-300x180.jpg)