In Gaza, the rubble and ruin must remain in full view not only as evidence of war crimes, but as living testimonies of shattered lives.

The ethnic cleansers operate with the hope that, in destroying these locales, Being-with, the heterogeneity constitutive of existence, will similarly be destroyed. The second phase of urbicide is aimed at covering over this heterogeneity with the suggestion that in the absence of the buildings there can be no Being-with, no co-existence.

Arie Amaya-Akkermans

Few remember today the UN Fact Finding Mission on the Gaza Conflict, known as the Goldstone Report. It was established in 2009, by jurist Richard Goldstone following Operation Cast Lead, and investigated violations of international human rights and international humanitarian law by the Israeli army and Palestinian armed groups, particularly in the Gaza Strip. At the time, no previous Israeli offensive had killed more Palestinians or caused more material damage —1,400 Palestinians were killed and about 15,000 buildings were destroyed or damaged. Goldstone reported at least 36 cases in which Israel deliberately targeted civilians, and “the people of Gaza as a whole,” coinciding with reports of human rights groups on a number of violations that are commonplace today: Israeli soldiers firing at women and children carrying white flags, preventing medical aid and ambulances from reaching wounded Palestinians who bled to death in the interim, and the wanton destruction of homes and neighborhoods.

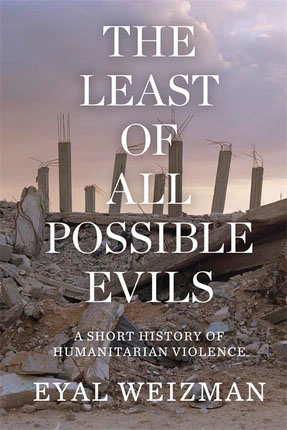

The Goldstone report set forth a precedent in which the shelling and demolition of Palestinian cities was no longer simply deterrence or a means to an end, but a violation of human rights in itself, although one still today without a clear legal framework. And Goldstone’s findings did not stop at the destruction of housing. Chapter XIII of the report is devoted to attacks on the foundations of civilian life in Gaza: Destruction of industrial infrastructure, food production, water installations and sewage treatment plants, alongside housing. Eyal Weizman, an Israeli architect and foremost expert on the urban planning aspects of the occupation, notes in his book The Least of All Possible Evils: Humanitarian Violence from Arendt to Gaza (2012) that, “In discussing its approach to the investigation of war crimes, the ‘methodology’ section of the Goldstone report reveals a slight — yet significant — shift of emphasis from human testimony to material evidence.”

Urban destruction, for the first time, occupied a central position in a human rights investigation in Palestine and was not simply regarded as collateral damage.

Urban destruction is, in fact, a central element of policy in the Occupied Territories: The Israeli Committee Against House Demolitions (ICAHD) has argued in the past that since 1967, Israel has demolished more than 18,000 Palestinian houses. Demolitions in Palestine are not only perpetrated by the Israeli army but also by strictures of urban planning; a rigid planning policy with regard to Palestinian homes makes it exceptionally difficult to obtain planning permission from municipalities and thus many constructions are deemed “illegal” and routinely demolished.

These numbers, however, are no longer extraordinary today, especially not in the face of the ongoing extermination campaign against Gaza by the Israeli army, now entering its third month. Operation Iron Swords is a retaliation campaign for the deadly attack by the militant group Hamas on October 7th that killed just under 1,200 people, 695 of them civilians, and abducted about another 240, civilians and military personnel both. Israel vowed to eliminate Hamas. So far this has proved unsuccessful. At one point it was said that the war could last as long as ten years, but it was also announced that it would continue for two months, or a few weeks. No one knows.

With a death toll of over 20,000, the facts on the ground in Gaza are shocking even for the extremely low bar of asymmetrical warfare in Palestine, and without access to the Gaza Strip or a ceasefire in place, information about both displacement and urban destruction fluctuates a lot and is collected on the basis of analysis of satellite images and informal reports, which cannot be verified.

The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs released a flash update on December 10, estimating that 85% of the population has been internally displaced. On December 15, The Economist’s satellite analysis found out that almost 43,000 buildings in Gaza (16% of the total) have been damaged and 450,000 are homeless (20% of the population), while at the beginning of December, satellite images commissioned by the BBC revealed that around 100,000 buildings have suffered heavy damage. This discrepancy indicates an extremely chaotic situation in development, where real numbers are expected to be higher than any estimates.

The scale of the damage is almost without parallel. For comparison, the 4-year-long Battle of Aleppo (2012-2016) destroyed approximately 35,000 buildings in an area over four times larger than the Gaza Strip. The Getty Publications book Cultural Heritage and Mass Atrocities considered Aleppo then one of the worst urban battles fought in the 21st century due to its length and level of destruction. Today, the entirety of northern Gaza, including Gaza City, the Jabalia refugee camp, and the northeastern cities of Beit Lahia and Beit Hanoun, have been nearly turned entirely to rubble, and southern enclaves such as Deir al-Balah, Khan Younis and Rafah have also been targeted.

On November 15, Israeli journalist Anshel Pfeffer wrote that “the largest Palestinian city in the world will soon be uninhabitable,” and speculated that, “We may be near the point where there are more Israeli soldiers in Gaza City than Gazans.” A concerted effort of demolition is underway, and, going sector by sector and house by house, any building suspected of harboring weapons or tunnel entrances is bombed or bulldozed, or both.

The archaeology of fresh rubble provides clues about the destructive weapon that caused it, based on the type of ruins: D9 bulldozers, dynamite, anti-tank landmines, aerial bombs, delay-fuse aerial bombs or “knock on the roof procedures.” But the most efficient weapon of urban destruction used against Palestinians isn’t necessarily violence as such, always merely instrumental, but rather the urban fabric itself.

Commenting on the Goldstone report in The Least of All Possible Evils, Weizman established an unsurprising correlation between the destruction of buildings and the immense loss of lives:

“A large proportion of the deaths occurred within buildings. Indeed, many individuals and families were killed by flying debris – the shattered concrete and glass of what used to be the walls, ceilings and windows of their own homes. The built environment became more than just a target or battleground; it was turned into the very thing that killed.”

Weizman is not alone in arguing that the destruction of buildings is one of the most visible confirmations of ethnic cleansing and genocide, for, as he notes, rubble and architectural destruction as evidence of war crimes was presented before the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, during the trial for the Kosovo War in 1999. That context of the Yugoslav Wars is important here, for it was in 1992 that a group of Bosnian architects from Mostar, in the publication Mostar ‘92–Urbicide, characterized the destruction of buildings in the city as a central aspect of the war and argued that the destruction of the built environment should be considered under the separate category of urbicide. In an influential study, Urbicide: The Politics of Urban Destruction (2009), political theorist Martin Coward, explains the term as, “the claim that the destruction of the built environment has a meaning of its own, rather than being incidental to, or a secondary feature of, the genocidal violence (or ‘ethnic cleansing’) that characterized the Bosnian War.”

The difference between genocide and urbicide is porous and difficult to establish, but Coward provides interrelated but distinct definitions: Genocide is “a coordinated plan of different actions aiming at the destruction of essential foundations of national groups, with the aim of annihilating the groups themselves,” whereas urbicide is a “coordinated plan of different actions aiming at the destruction of the built environment: buildings, infrastructure and monuments in particular.” Although Coward distinguishes both conceptually, he also notes that the nature of the execution of these forms of violence may not in fact differ.

Drawing on an obituary written by Croatian writer Slavenka Drakulic in 1993 for the 400-year-old Stari Most bridge in Bosnia, destroyed by the HVO (Croatian Defense Council), in which she argues that the destruction of the bridge is not simply an assault against civilian infrastructure but the “destruction of the possibility of duration of a specific community,” Coward develops a formal understanding of the logic of urbicide.

Based on cases from Bosnia, the West Bank and Chechnya, he argues that urbicide is the destruction of the condition of the possibility of being with others. When Palestinian cities are destroyed, what is destroyed is not simply residences, public spaces, and infrastructure but the “city” as such; a permeable and difficult to define assemblage of human and non-human relations, memories, locales, and institutions. Coward notes that the argument isn’t prioritizing buildings over people, but instead, highlighting Drakulic’s point that existence is only possible as a community.

One of the most important nuances in Coward’s work is that urbicide doesn’t necessarily destroy the complex assemblages of the city, for, “after all, destruction is never complete—ruins, memories and histories always remain.” To destroy the built environment of a locale isn’t to destroy the assemblage, but to “cover it over” and deprive the population of it. If the destruction is sustained or allowed to go unchallenged, the rupture between peoples and their urban assemblages might become normalized: “The ethnic cleansers operate with the hope that, in destroying these locales, Being-with, the heterogeneity constitutive of existence, will similarly be destroyed. The second phase of urbicide is aimed at covering over this heterogeneity with the suggestion that in the absence of the buildings there can be no Being-with, no co-existence.”

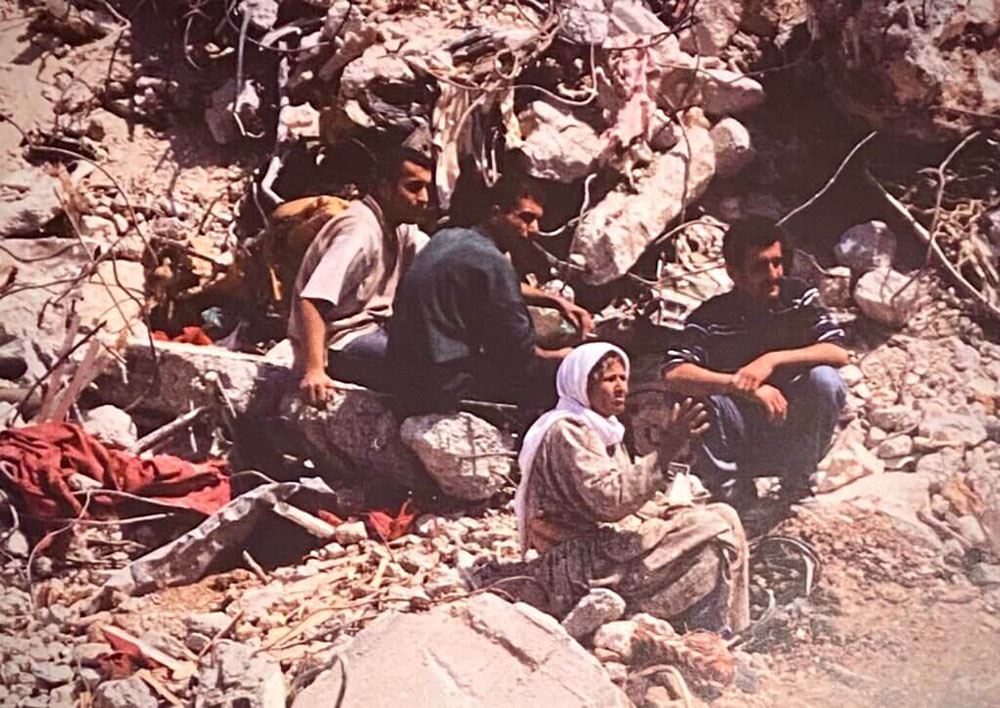

In the aftermath of the Battle of Jenin, in 2002, urbanism expert Stephen Graham described the leveling by Israeli bulldozers of a 300-by-250-meter area in the refugee camp as asymmetrical urbicide. Not only did the demolition bury civilians alive and leave over 4,000 people homeless, but Graham also recounts reports of Israeli soldiers using detailed maps to carefully mark houses for demolition, and the army blocking all attempts at rebuilding and removing unexploded ordnance.

Coward notes the difference between a scorched earth policy, a military strategy conceived to destroy significant buildings with the aim of disempowering the enemy and removing anything that might be useful to the opposing military, and rubblization, which is intended to reduce the built environment as a whole to rubble. Russian tactics during the Chechen campaigns in 1994-1996 and Israeli house demolitions in Palestine belong to the latter category.

The legal figure of ‘wanton destruction,’ enshrined in International Humanitarian Law, constitutes a war crime, based on a 2001 ruling by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, if any of the following three conditions are met: Destruction of property occurs on a large scale, the destruction is not justified by military necessity, and the perpetrator acted with the intent to destroy the property in question or in reckless disregard of the likelihood of its destruction.” In order to understand the systematic nature of wanton destruction in Palestine, it will be necessary to look into what we know about Operation Iron Swords.

According to Israeli daily Haaretz, the lack of restraint on the part of the Israeli army has translated into a rate of civilian deaths higher than any other assault on Gaza. The speed of killing, the number of airstrikes in an area three times smaller than the Jerusalem municipality, and the amount of ordnance dropped (over 29,000 munitions, over 40% of them unguided), makes Iron Swords unique not only in its disregard for civilian life, the massive urbicidal destruction and the scale of displacement, but also as a new chapter in the history of asymmetrical warfare that it has inaugurated, assisted by technology.

At the end of November, +972’s Yuval Abraham published a report diving into Israel’s “mass assassination factory,” detailing the army’s expanded authorization for bombing non-military targets, the loosening of constraints regarding civilian casualties from dozens to hundreds, and the use of artificial intelligence to generate more potential targets than ever before. The most alarming piece of information is the expansion of “power targets,” as distinguished from tactical and underground targets. These targets include high-rises, residential towers, and public buildings such as universities, banks and government offices. According to “three intelligence sources who were involved in planning or conducting strikes in the past” the report explains that, “The idea behind hitting such targets, is that a deliberate assault on Palestinian society will exert ‘civil pressure’ on Hamas.”

In the first five days only, the Israeli army attacked more than 1,000 power targets, causing mass devastation, unprecedented numerically, but consistent with the army’s Dahiya Doctrine. Formulated during the Second Lebanon War, the tactic assumes that disproportionate onslaughts on the civilian population will help pressure armed groups into submission. In the course of Cast Lead, Israel attacked 3,400 targets in 22 days, and yet during Iron Swords, it has struck 15,000 targets in the first 35 days.

The Israeli army has more than quadrupled the volume and speed of its destructive attacks since Cast Lead in 2009, without increasing the size of its active personnel. In November, the army spokesperson revealed that they are using an AI system called “Hasbora” (The Gospel), which enables automated, high-speed production of targets in real time. These are automatic recommendations for attacks on “operative homes,” with the purpose of destroying residences of suspected members of Hamas or Islamic Jihad. Although little is known about the data ingested into the system, AI experts told The Guardian that decision support systems would likely be analyzing data from drone footage, intercepted communications, surveillance data and monitoring of movements and behavior patterns.

This would make the potential for targets near infinite since Israel estimates that there are approximately 30,000 Hamas members in Gaza. In practice, the system has turned into an uncontrolled killing machine: Homes of suspected Hamas members are now targeted regardless of rank. An army official, involved in targeting decisions in previous Gaza operations, told +972’s Abraham: “This is a lot of houses. Hamas members who don’t really mean anything live in homes across Gaza. So they mark the home and bomb the house and kill everyone there.”

Aviv Kochavi, Chief of General Staff in the Israeli army between 2019 and 2023, pioneered the creation of a secretive unit in the Israeli army tasked with accelerating target generation. But as it turns out, the Gospel system wasn’t that secret: It has been in use since 2021, and in an interview prior to October 7th, Kochavi said that it was “a machine that produces vast amounts of data and more effectively than any human, and translates it into targets for attack.” Even more perplexing is what the target bank chief told the Jerusalem Post: AI targeting capabilities had for the first time brought the army to a point where it can assemble new targets even faster than the rate of attacks. This addressed a chronic problem in the defence establishment in earlier operations in Gaza, that the air force was constantly running out of targets.

With a near infinite target bank in the horizon, the Israeli army effectively transitioned into algorithmic warfare. But the total mathematization of Gaza’s entire urban space as a cubic lattice, or three-dimensional grid, at the receiving end of an AI-powered DSS (decision support system), is not simply a collateral effect of the technological and cultural transformations of geophysical space, from flat cartography and linear combat to the systems and infrastructures of “deep maps” and global positioning systems. Instead, this shift is preemptively embedded in the occupation’s thinking about architecture and space and its treatment of the Palestinian urban fabric as a laboratory.

The case of Kochavi, the mastermind of “Gospel,” gives us an incredible insight into the lethal combination between architecture, theory, technology and violence in the service of the occupation. Drafted into the army in 1982, Aviv Kochavi has taken part in almost every major conflict in Israel since then, including 8 different operations in Gaza and the West Bank since 2006, the first and second Intifada, the Lebanon wars in 1982 and 2006, and the security zone in southern Lebanon between 1985 and 2000. As a commander of the paratroopers brigade, he led Operation Defensive Shield (2002), and other operations in the West Bank against Palestinian militant infrastructure.

Kochavi’s biography sheds light on the vastly underestimated intersection between contemporary theory and military strategy in the career of a war criminal-philosopher: Kochavi canceled a trip to Britain in 2006, fearing possible arrest and prosecution for war crimes and indeed took time off from active duty to earn a degree in philosophy (although he intended to study architecture), and he claims that his military practice has been informed by both disciplines. He also attended courses at the now defunct army think tank OTRI (Operational Theory Research Institute).

Founded by Shimon Naveh and Dov Tamari, both retired generals, OTRI claimed to train “operational architects,” through an approach deeply influenced by poststructural and situationist thinkers such as Gilles Deleuze, Felix Guattari and Guy Debord, and employed doctoral candidates in philosophy or political science to do so. OTRI was curious about two aspects of post-1968 thinking about space and architecture: Non-state violence and the deconstruction of urban space. The Israeli army was trying to solve a fundamental strategic problem during the Second Intifada: Urban warfare is too messy and unpredictable for linear combat, and therefore a level of operational decentralization, resembling guerrilla tactics, is required. The concept of swarming was thus introduced into Israeli military practice, which according to Weizman, “seeks to describe operations as a network of diffused multiplicity of small semi-independent but coordinated units operating in general synergy with all others.” The Battles of Jenin and Nablus in 2002 demonstrated the ways in which urban space itself had already become weaponized.

In Hollow Land: Israel’s Architecture of Occupation (2007), Weizman writes about the maneuver conducted by Brigadier Kochavi in Nablus, described as “inverse geometry,” reorganizing urban syntax by means of avoiding streets, roads and public spaces, as well as external doors, stairwells and windows: “They were punching holes through party walls, ceilings and floors, and moving across them through 100-meter-long pathways of domestic interior hollowed out of the dense and contiguous fabric. The tactics of “walking through walls” involved a conception of the city as not just the site, but as the very medium of warfare — a flexible, almost liquid matter that is forever contingent and in flux.”

Kochavi developed the use of a 5kg hammer to break down walls and cross through homes in refugee camps, by means of “walking through walls,” in order to prevent his soldiers being shot by snipers. A novel thinking about space had been introduced, which would become influential in the military establishment under Moshe Ya’alon as chief of general staff between 2002 and 2005.

The following passage in Weizman’s book is mind blowing, connecting the battlefield with military-funded research:

“In their book, A Thousand Plateaus, Deleuze and Guattari draw a distinction between two kinds of territoriality: a hierarchical, Cartesian, geometrical, solid, hegemonic and spatially rigid state system; and the other, flexible, shifting, smooth, matrix-like ‘nomadic’ spaces. Within these nomadic spaces they foresaw social organization in a variety of polymorphous and diffuse operational networks. If these networks, rhizomes and war machines are organizations composed of a multiplicity of small groups that can split up or merge with another depending on contingency and circumstances and are characterized by their capacity for adaptation and metamorphosis. These organizational forms resonated in themselves with military ideas such as those described above.”

OTRI’s concept, known as ‘systemic operational design’, however was ultimately blamed for Israel’s failure in the Second Lebanon War and the institute was disbanded in 2006. A recent study on SOD (systemic operational design) by Polish military historian Łukasz Przybyło, provides gripping insights into OTRI’s critique by the traditional military establishment: SOD was too complicated to follow and to understand; Kochavi’s victories in the West Bank were considered obvious in a situation of almost total technological and intelligence superiority, and Ya’alon’s replacement as chief of staff in 2005, Dan Halutz, was not familiar with operational research, which was based on postmodern thought, architectural studies, anthropology, etc. This critique, however scathing, underestimates the uncanny familiarity between SOD and the violent architecture and spatiality of the occupation at large.

In the shift from the movement through walls in the West Bank, defying the logic of urban space, to the war algorithm embodied in the killing machine of automation bias and decreased decision-making time for human operators in Gaza, defying the logic of optical space (a mathematical coordinate system), the Israeli army is engaged in the same strategic maneuver that has dominated their thinking about the architecture of the occupation: Using technology, the built environment and the para-legality of the occupation itself as tools to shape human geography with difficult-to-classify instruments such as checkpoints, turnstiles, separation walls co-designed with both litigants and settlers, networks of parallel roads, aleatory observation points, tunnels and air surveillance. The procedure is deceivingly complex (just like SOD) and replete with legalese, but the strategy is unambiguous: Swarming as spatial politics.

Spatial swarming seeks to achieve two simultaneous, and apparently contradictory goals: The meticulous fragmentation of Palestinian urban space while at the same time consolidating all spaces—political, geographical, virtual—into a layer-cake in which the power of the state is omnipresent. The aim is ultimately to trap Palestinians inside this honeycomb, both vertically and horizontally.

The mathematization, and hence fragmentation of urban space in Gaza is therefore no metaphor but an actual macabre reality: Israel has started using a new grid system for evacuation that has broken Gaza down into more than 600 blocks in order to shuffle civilians around in an increasingly shrinking space. People may access the grid through QR code—knowing that no one in Gaza has regular access to the Internet or electricity. The grid obviously doesn’t achieve much in terms of minimizing the damage inflicted on civilians, serving perhaps only to further disorient them. But it does open a window into the level of normalization and dehumanization that exists in the Israeli army, seamlessly merging military strategy, geophysical space, “humanitarian obligations” and decision support systems.

The Israeli army understood long ago that its violations continue to shape humanitarian law, therefore it is constantly pushing and stretching those boundaries. Kochavi, now enjoying happy retirement after an illustrious career, might have, with “Gospel,” crossed the final boundary in the atomization and decentralization of space in the Palestinian territories by removing the last safety valves in the quest for a total, but wholly diffuse, abstract and ‘granular’ dominion over Gaza.

It is here that we begin to read an oft quoted passage from Deleuze and Guattari’s Thousand Plateaus through OTRI’s eyes: “What interests us in operations of striation and smoothing are precisely the passages or combinations: how the forces at work within space continually striate it, and how in the course of its striation it develops other forces and emits new smooth spaces.” It has thus become a manual of urban warfare.

In the urbicide of Gaza, the elasticity of buildings, expanding and contracting with temperature, humidity, air and violent force, is doubly used as both a weapon of destruction and tool for swarming space. On the one hand, people are killed by buildings, injured, maimed and buried alive. The home that once provided safety becomes a blunt object that crushes bodies. These are the forces at work that striate space. On the other hand, the resulting rubble of the striation is a toxic material, difficult to remove and is presented as the sign of the permanence of the destruction of communities. The rubble itself is the new smooth space that emerges from the striation: It covers the assemblage of the city over, it renders invisible the community and its assemblage of relations with the built environment.

But the extraordinary damage on the thin ground surface where Palestinians live and die, squeezed between Israel’s total aerial superiority and Hamas’ cowardly dominion of the underground, encompasses not only the communities of the present, but also long-term memory: Al-Haq reported on the damage of 104 out of 325 heritage sites in Gaza, as well as the destruction of the coastline, including well-known archaeological sites, such as the Hellenistic-Roman city of Anthedon. These are crimes against humanity in a deeper sense than those stipulated by current legislation. The crime is not simply the physical destruction of communities, but the incomparably cruel mechanism of preventing complexity from being restored; thus condemning Palestinians to a disentangled existence, in which the relations they enter into with the built environment, or rather with the rubble, become fragile, accidental and wholly dependent on capricious power.

However, as Weizman has noted in The Least of All Possible Evils, new generations of Palestinian scholars and architects, are not passively witnessing disempowerment and they have attempted to strengthen refugee camps, and hence, the rubble itself, into political spaces, as well as memory sites that reinforce the mobilization against the occupation, with gestures such as The Book of Destruction, a list of all Gaza’s buildings damaged during Cast Lead. The rubble, the ruin, and the camp, these forcibly striated spaces, must remain in full view, at least for now, as a testimony of the assemblages that urbicidal violence attempted to erase. This is the return to the ruin that Ariella Azoulay advocated recently: “We must return to what was destroyed, to the ruins and the possibilities that were doomed to appear as past”. As silent bystanders, we must not look away: In the presence of this archaeology of the not-quite-past, what we see is not beyond the borders of time, but a titillating present, violently oozing out from everywhere.

Endnote

This essay is partly based on the public presentation, “From Alalakh to Gaza: The Archaeology of Urban Destruction”, delivered by the author at Voga Art Project, in Bari, Italy, November 21st. Acknowledgements: Nicola Guastamacchia & Flavia Tritto.