Two recently published works rely on short vignettes to capture a reality similarly disturbing and disorienting.

Witness to the Hellfire of Genocide: A Testimony from Gaza, by Wasim Said

1804 Books 2025

ISBN: 9798999019516

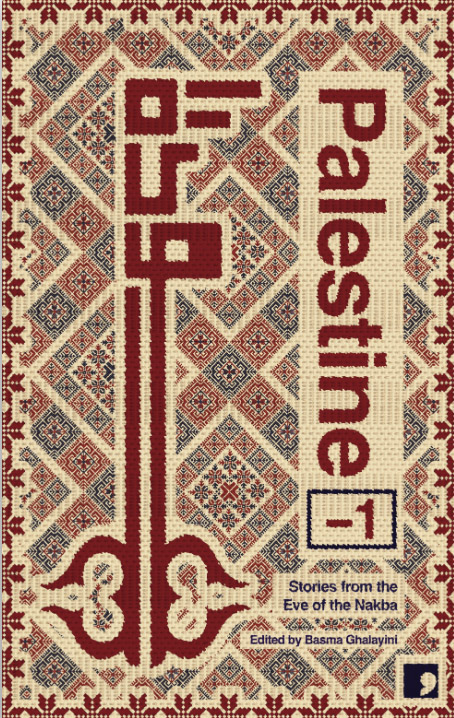

Palestine Minus One: Stories from the Eve of the Nakba, edited by Basma Ghalayini

Comma Press 2025

ISBN: 9781917093026

During Israel’s genocide in Gaza, the anthology of short vignettes has emerged as a form that feels particularly appropriate for Palestinian art. The rapid move from the end of one story to the beginning of another can disturb and disorient, reflecting the fragmentation, impermanence, and unpredictability of life under forced displacement and deadly bombardment. It’s a form that also acknowledges the importance of representing a multitude of different experiences of ethnic cleansing, apartheid, and genocide. For western audiences, it approximates the way many of us receive images and information — not filtered through the news bulletins of media corporations that barely hide their hostility toward Palestinians, but through short-form social media videos often directly produced by the young citizen-journalists of Gaza.

In film, this storytelling form is used to devastating effect in From Ground Zero, director Rashid Masharawi’s anthology of 22 short films by Gazan filmmakers. It can be also seen in Annemarie Jacir’s Palestine 36, which immerses us in a historical retelling of the 1936 Arab Revolt through a large cast of characters with stories both self-contained and interlinked. Two new books show this approach to be equally impactful in literature.

Wasim Said’s Witness to the Hellfire of Genocide is not exactly an anthology, but its rapid pace and the scattered anecdotes related by its author — a university student studying physics before the outbreak of genocide — make it feel like one. It is written in the khatira style of Arabic literature, best translated as a collection of “impressions,” a genre somewhere between prose and poetry. The short paragraphs, often a single sentence long, have the effect of making every word seem emphasized. While Said’s book is brief enough to be read in a single sitting, the contents are so viscerally harrowing that it’s difficult to bear more than a few pages at a time. One quickly realizes that reading about the reality of genocide demands far more effort than watching it via social media videos, passively absorbing the situation through a succession of clips.

Recurrent throughout the pages of Witness is the sense of ordinary life (if life under the devastating blockade Israel maintained on Gaza for sixteen years before October 2023 can be considered “ordinary”) disrupted with unimaginable force. Before the genocide, Said was, in his own words, a “university student passionate about the sciences and physics,” with “a cultured and educated family.” Much of the book revolves around the consequences of Israel’s man-made famine, and the lengths to which Palestinians in Gaza must go to obtain the most basic of foodstuffs. Eighteen months into the genocide, Said bitterly notes:

and now one of our greatest dreams is having a sack of flour. Flour had never been something we thought about, but now that same flour consumes our thoughts and dreams and aspirations. My dream of being an explorer of this universe has been replaced, buried by the dream of securing a sack of flour…

Said’s book also explores the stories of the people around him, like family friend Uncle Abu Malek, his university friend Mousa, and the “anonymous man in the market,” who poignantly asks the writer, “Young man, if the blood of those I love have not aroused the sympathy of the world yet, do you think that your words will?” Said is unsure. Yet his short book burns with a fierce sense of purpose:

This isn’t mere literature.

It’s a testimony under fire.

A voice in a time when truth is no longer

to be found on screens.

A testimony from a wound that refuses to heal,

so its voice may remain alive.

Basma Ghalayini’s edited collection Palestine Minus One seems a very different kind of book on the surface. A conceptual inversion of the Palestine +100 anthology, which asked contemporary Palestinian writers to imagine Palestine a century into the future, the stories here have the writers going back to the eve of the Nakba in 1948. Many of the stories take a surrealist or magical realist approach to “addressing,” as Ghalayini writes, “the great crime that underpins the entire occupation.” Mazen Maarouf’s “A Chronicle of Grandad’s Last Days Asleep” eerily describes a Palestine populated with the ghosts of those killed by Zionist militias, condemned to aimlessly repeat bizarre actions or wander in search of villages they cannot quite remember, now inhabited by “strangers.” “In one town,” Maarouf writes:

the hands of the municipal clock always go back to the position they were in when the people had been driven out. That happens three or four times a day. When people look at the clock tower, they often find it shows ten minutes after noon. Since the residents left, the furniture in some of the houses doesn’t like to be moved around. In one beautiful house, the strangers wake up every morning to find that the furniture has rearranged itself the way it was when the owners left the house…

In writing about the Nakba, it’s clear that Palestinian authors are often also writing about the Gaza genocide. Again, as Ghalayini writes, the aim of the book was to explore how “literature [might] respond to a genocide,” to ask whether it is “even possible to write fiction after witnessing the horrors inflicted on Gaza.” The harrowing description in Ibtisam Azem’s “Ismail al-Lyddawi,” of the July 1948 massacre in the Dahmash Mosque in the city of al-Lydd, for example, cannot but remind readers of much more recent massacres committed by the same military. This more than anything underscores the point of the anthology, reminding us that the Nakba was not a singular event but one that is ongoing and ever-present.

Not every story hits its mark. George Abraham’s “Flood” provides a disappointing finale to the collection. Abraham’s protagonist is a sexually voracious gay Floridian Jew, with a background that is “culturally Jewish at best, maybe,” and who settles in Tel Aviv out of “equal parts boredom and horniness.” The character is recruited by Israeli intelligence to “catfish” gay Palestinians, before ending up at the Nova Festival near the Gaza border on October 7, 2023. It is an intriguing premise, which might have worked more effectively over a longer novella or novel. Yet constricted to 30 pages, the Israeli characters are clichés, making flat proclamations like, “I don’t know which I love more, my country or the thought of killing Arabs for her,” or having desert rave revelations such as “what the fuck are any of us doing here?!?!” Giving full voice to his character’s graphic sexual fantasies, Abraham also risks affirming the Zionist hasbara of Israel as “the gay capital of the Middle East,” which he set out to critique.

It’s when the stories are least ostentatious, and most focused on atmosphere and character, that Palestine Minus One really shines. “Katamon” by British Palestinian author Selma Dabbagh impresses with its intricately drawn character sketch of Berthe Grünfelder, the real-life widow of André Serot, a French colonel assassinated while on peacekeeping duties in Jerusalem by the Lehi Zionist terror group. Grünfelder struggles to comprehend both Serot’s murder and the war enveloping the upscale neighborhood of western Jerusalem from which Dabbagh’s story takes its name. Grünfelder observes the gradual disappearance of Katamon’s Palestinians, such as the unnamed yet fondly remembered “young doctor friend,” who “[took] a short trip to Beirut in April as the fighting was disrupting his ability to study” and was subsequently unable to return to Jerusalem. Dabbagh hints that Grünfelder’s wartime experiences in a Nazi concentration camp — referenced obliquely in “the blue number that I disliked very much” tattooed on her wrist — lie behind her inability to fully process the personal and national tragedies around her. The trauma of the Nakba and that of the Holocaust are linked in a way that is subtle and deeply sensitive.

Liana Badr’s “I Swear, All This Happened” is another understated gem. Both Dabbagh’s and Badr’s stories are set in Jerusalem, the authors perfectly capturing the bewilderment and grief felt by an international or relatively upper-class milieu at the destruction of the city’s social foundations. The story opens in Dar al-Tifl al-‘Arabi, a school and orphanage established by the prominent Palestinian social activist Hind al-Husseini for child survivors of the Deir Yassin massacre, committed by the Irgun Zionist militia in April 1948. A light touch of magical realism means we are unsure whether folkloric creatures really lurk in the corridors, or are figments of the children’s imaginations. We see a djinn which “spent the night standing by [girl student] Imtiyaz’s bed,” and “told her that it was tired of being alone, with no family or neighbors.” Decades later, Badr reveals, Imtiyaz is killed by American bombing of Iraqi-occupied Kuwait, a reminder that the Nakba’s legacy has stalked Palestinians wherever they have gone, a more malevolent kind of djinn.

Nevertheless, ever since the Nakba, successive generations of Palestinian artists — filmmakers, musicians, visual artists or, as here, writers — have turned their people’s struggle into expression which is as vibrant as it is sorrowful, timeless additions to a growing canon as much as calls to action in the present moment. Witness to the Hellfire of Genocide and the short stories of Palestine Minus One show that this tradition remains not only unbroken in the darkness of the Gaza genocide, but more powerful and relevant than ever. In Wasim Said’s “voice [that] may remain alive,” there is an affirmation of Palestinians’ steadfast commitment to documentation and the refusal to keep silent. A commitment perfectly captured in the trajectory of Ibtisam Azem’s titular character Ismail al-Lyddawi, who regains his lost voice 77 years after the Nakba with a final act of resistance. These writers are part of the Palestinian voices, which Israel has always tried, and will always fail, to silence. We have a duty to listen.

![Fady Joudah’s <em>[…]</em> Dares Us to Listen to Palestinian Words—and Silences](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/SAMAH-SHIHADI-DAIR-AL-QASSI-charcoal-on-paper-100x60-cm-2023-courtesy-Tabari-Artspace-300x180.jpg)