The former Beit Lahia resident won a Pulitzer on Monday for a series of essays he published in the New Yorker in 2023 and 2024, recounting his experiences as he and his family struggled to survive.

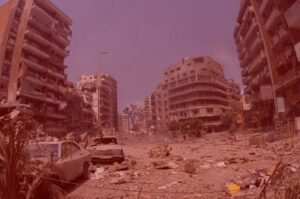

Back in the summer of 2021, we were working on a special issue devoted to Gaza. You’ll remember that Gaza had already been subjected to withering military assaults by Israel in 2008-2009 and in 2014 (Operation Protective Edge), which wrought a great deal of destruction and death. Mosab Abu Toha was an aspiring writer, who, like most Gazan youth had lived through those crises. In 2014, he graduated from the now destroyed Islamic University of Gaza, and participated in We Are Not Numbers (WANN), a youth-led Palestinian initiative that until today provides training in English to developing storyteller–journalists, allowing them a better chance of reaching the world beyond Gaza’s closed borders. Greatly inspired and partly led by the late scholar and poet Dr. Refaat Alareer, WANN has launched the careers of a number of writers from Gaza who have gone on to make a name for themselves on the international stage, including Shahd Safi, who has written for the Los Angeles Times and Mondoweiss, and Hind Khoudary, one of the most prominent young journalists left in Gaza, who has been tirelessly documenting the genocide for Al-Jazeera, among other media outlets.

Mosab, a lover and collector of books, was committed to building his life in Gaza and contributing to its cultural scene. He created the Edward Said Memorial Library, stocking it with English-language books and he wrote honest poems about his life in a second language. The work was so good that he caught the attention of poet-translator Ammiel Alcalay, who then strongly recommended him to TMR.

And so, in July 2021, in TMR 11 • GAZA, we ran four poems by Mosab, which later appeared in his first collection, Things You May Find in My Ear, published by City Lights in 2022. Less than a year later came Hamas’ surprise attack on Israel on October 7, 2023, and the next day, a vengeful onslaught by Israel on the entirety of the Gaza Strip. Once again, the Palestinians of Gaza were forced into mobilizing to survive yet another Israeli assault. Like so many of his friends, colleagues and readers abroad, we found ourselves frantically following Mosab’s social media dispatches as he chronicled, in both English and Arabic, the extraordinary terrors and daily indignities of Israel’s genocidal war.

In the winter of 2023, Israeli bombs, likely manufactured in and supplied to Israel by the United States, destroyed the four-story flat where Mosab and his extended family had been living. Everyone dispersed, and Mosab and his wife Maram began considering the possibility of leaving Gaza. “When Maram and I talk about leaving,” he wrote in his first New Yorker essay published in December of 2023, “we understand that the decision is not only about us. It is about our three children. In Gaza, a child is not really a child. Our eight-year-old son, Yazzan, has been talking about fetching his toys from the ruins of our house. He should be learning how to draw, how to play soccer, how to take a family photo. Instead, he is learning how to hide when bombs fall.”

The family decided to head to Cairo. On the way to the Rafah border crossing with his wife and children, Mosab was pulled out of the line at a checkpoint, detained and beaten by the Israeli army. He was already known enough by then that news of his kidnapping led to an avalanche of protests about his kidnapping, and it is this perhaps that earned his subsequent release. From Cairo, the family went on to the US, where Mosab continued writing about life in Gaza for the New Yorker and assembling his second collection of poems. Forest of Noise was published to much acclaim by Knopf last October.

While Palestinians and pro-Palestinian activists were already facing repression under the Biden administration, with student protesters on campuses across the country hounded by administrators and often rounded up and arrested by local authorities, the situation became exponentially more dire after the new American administration came to power in January 2025. Following the arrest of recent Columbia graduate Mahmoud Khalil by ICE, Mosab found himself on a list among a number of other activists, compiled by the extremist Zionist group Betar to identify “undesirables” for ICE deportations. Fearing for his safety, Mosab made the heartrending decision to cancel his Forest of Noise book tour, feeling it safer to stay close to home, with his family.

Just before the administrative chaos was unleashed in full, however, we had the good fortune to be able to include Mosab in a presentation of our book Sumūd: A New Palestinian Reader at NYU on the 5th of February, in a panel that included me and my co-editor Malu Halasa, as well as fellow contributor and TMR senior editor Lina Mounzer, and NYU moderator Mohamad Bazzi. Mosab read his poems to a standing ovation, warmly thronged by readers and admirers in the aftermath of the panel.

While extremist pro-Israel groups continue to focus their attention on any and all pro-Palestinian voices, hoping to intimidate them into silence, Mosab insists on continuing to make his voice heard in US and international fora. His poetry, essays and activism compel us to face the horrors Gaza is being made to endure, including forced starvation and massacres by the IDF. He also insists on staying in the US — after having already made the heartbreaking decision to flee home once, he and his family are reluctant to tear out the roots they’ve begun to grow in this new place. They are already en route to citizenship and despite an openly hostile administration, the enormous amount of solidarity and support for Gaza and for the Palestinian cause in general among so many in the US is further encouragement to remain and fight from within the empire that is funding, arming and providing political support and cover for the Zionist state.

Having known so much war over the course of his young lifetime, Mosab has in effect become one of the most cogent and moving voices for Gazans struggling to survive Israel’s savage punishment of the Palestinian population. Israel has broken international law time and again by bombing into oblivion hospitals, schools, universities and houses of worship, killing men, women and children indiscriminately. The rules of war as described in the Geneva Conventions have been ignored by Israel and abused, with impunity. More than 50,000 people are dead, with over 100,000 wounded. In fact, according to the Lancet, the numbers are probably much higher.

Mosab Abu Toha’s 2025 Pulitzer Prize in Commentary was awarded for his series of essays on Gaza published over the course of 2023-2024 in the New Yorker. In celebrating his win on X, Mosab quoted Dr. Refaat Alareer: “Let it bring hope / Let it be a tale.” While Alareer was tragically murdered by Israel, his proteges from We Are Not Numbers continue his legacy, fulfilling the project’s fundamental mission of allowing Gaza’s writers to represent themselves and their homeland in their own words. On behalf of The Markaz Review and our valued members and readers, we congratulate Mosab Abu Toha on his Pulitzer win. The prize recognizes the supreme timeliness and urgency of Mosab’s words, and reminds us that we are all implicated in this urgent, historical moment as a premeditated genocide unfolds before the eyes of the entire world. Nothing could be a starker illustration of the fact that none of us are free until Palestine and Palestinians are free.

•

Mosab Abu Toha

PALESTINE A–Z*

A

An apple that fell from the table on a dark evening when manmade

lightning flashed through the kitchen, the streets, and the

sky, rattling the cupboards and breaking the dishes.

“Am” is the linking verb that follows “I” in the present tense when

I am no longer present, when I’m shattered.

B

A book that doesn’t mention my language or my country, and

has maps of every place except for my birthplace, as if I were an

illegitimate child on Mother Earth.

Borders are those invented lines drawn with ash on maps and sewn

into the ground by bullets.

C

Gaza is a city where tourists gather to take photos next to destroyed

buildings or graveyards.

A country that exists only in my mind. Its flag has no room to fly

freely, but there is space on the coffins of my countrymen.

D

Dar means house. My grandparents left their house behind in

1948 near Yaffa beach. A tree my father told me about stood in

the front yard.

Dreams of children and their parents, of listening to songs, or

watching plays at Al-Mishal Cultural Center. Israel destroyed it in

August 2018. I hate August. But plays are still performed in Gaza.

Gaza is the stage.

E

An email account that I used when the power was on, the email

through which I smelled overseas air. I used it first to send photos

to my aunt in Jordan, who we last saw in 2000.

How easy it becomes to recognize what kind of aircraft it is: an

F-16, helicopter, or a drone? What kind of a bullet it was: from a

gunboat, an M-16, a tank, or an Apache? It’s all about the sound.

F

Friends from school, from the neighborhood, from childhood. The

books in my living room in Gaza, the poems in my notebooks, still

lonely. The three friends I lost to the 2014 onslaught: Ezzat, Ammar,

and Ismael. Ezzat was born in Algeria, Ammar in Jordan, Ismael on

a farm. We buried them all under the cold ground.

Fish in our sea that the fishermen cannot catch because the Israeli

gunboats care about sea life in the Mediterranean. They once fished

at the Gaza beach with a barrage of shells, and Huda Ghalia lost

her father, stepmother, and five siblings in June 2006. I walked

in their funeral procession to the cemetery. Blood was still fresh

on their clothes. They had poured out some perfume to cover the

stench. Over time my hate for perfume grew intense.

G

How are you, Mosab? I’m good. I hate this word. It has no meaning

to me. Your English is good, Mosab! Thanks.

When I was asked to fill out a form for my J-1 visa application,

my country, Palestine, was not on the list. But lucky for me, my

gender was.

H

If a helicopter stops in the sky over Gaza, we know it’s going to

shoot a rocket. It doesn’t see if a target is close to children playing

marbles or soccer in the street.

My friend Elise told me hey is a slang word and shouldn’t be used.

“English teachers would faint at what goes on today in written

English,” she said.

I

Images on the walls of buildings, a child who was shot by an

Israeli sniper, or killed during an air raid en route to school. Her

picture was placed on her desk at school. Her picture stares at the

blackboard, while the air sits in her chair.

I wake up ill when gloomy ideas about what might’ve happened to

me come in my dreams, what if I had stopped for a few seconds at

the window when a bullet from nowhere ripped through the glass.

J

Once I sent a picture of my desk in Gaza to a friend in the United

States. I wanted to show that I was fine. On the desk were some

books, my laptop, and a glass of strawberry juice.

When I sent that photo, I was jobless. About 47 percent of people in

Gaza have no work. But while writing these lines, I’m trying to

start a literary magazine. I still don’t know what to name it.

K

My grandfather kept the key to his house in Yaffa in 1948. He

thought they would return in a few days. His name was Hasan.

The house was destroyed. Others built a new one in its place.

Hasan died in Gaza in 1986. The key has rusted but still exists

somewhere, longing for the old wooden door.

In Gaza you don’t know what you’re guilty of. It feels like living

in a Kafka novel.

L

I speak Arabic and English, but I don’t know in what language my

fate is written. I’m not sure if that would change anything.

Light is the opposite of heavy or dark. In Gaza, when the electricity

is cut off, we turn on the lights, even in broad daylight. That way,

we know when the power’s back.

M

Marhaba means hi or welcome. We say Marhaba to everyone we

see. It’s like a warm hug. We don’t use it, however, when soldiers

or their bullets or bombs visit us. Such guests not only leave their

shit, but also take everything we have.

My dad used to prepare milk for us with some qirshalah before

school. I was in third grade, and my mother was at hospital taking

care of my brother. My brother died in 2016.

N

In 2014, about 2,139 people were killed, 579 of them were

children, around 11,100 were children, around 13,000 buildings.

were destroyed. I lost three friends. But it’s not about numbers. Even

years, they are not numbers.

A nail is used to join two pieces of wood or to hang things on

the wall. In 2009, the Israelis targeted an ambulance with a nail

bomb near my house. Some were killed. I saw many nails on our

neighbor’s newly painted wall.

O

Yaffa is known around the world for its oranges. My grandmother,

Khadra, tried to take some oranges with her in 1948, but the

shelling was heavy. The oranges fell on the ground, the earth drank

their juice. It was sweet, I’m sure.

In Gaza, we had a clay oven that our neighbor Muneer built for us.

When my mother wanted to bake, I fed it wood stems or cardboard

to heat it for the bread. The woody stems were made from dried

plants: pepper, eggplant, and cornstalks.

P

A poem is not just words placed on a line. It’s a cloth. Mahmoud

Darwish wanted to build his home, his exile, from all the words

in the world. I weave my poems with my veins. I want to build a

poem like a solid home, but hopefully not with my bones.

On July 23, 2014, a friend called and said, “Ezzat was killed.” I

asked which Ezzat. “Ezzat, your friend.” My phone slipped from

my hand, and I began to run, not knowing where.

What’s your name? Mosab. Where are you from? Palestine. What’s

your mother tongue? Arabic, but she’s sick. What’s the color of

your skin? There is not enough light to help me see.

Q

We were watching a soccer match. Comments and shouts filled the

room. The power was cut off, and everything became quiet. We

could hear our breathing in the dark.

Al-Quds is Arabic for Jerusalem. I have never been to al-Quds. It’s

around sixty miles from Gaza. People who live 5,000 miles away can

move there, while I cannot even visit.

R

I was born in November. My mother told me she was walking on the

beach with my father. It turned stormy and began to rain. My mother

felt pain, and an hour later, she gave birth to me. I love the rain and the

sea, the last two things I heard before I came into this horrible world.

S

I like to go to the beach and watch the sun as it sinks into the sea.

She’s going to shine on nicer places, I think to myself.

My son’s name is Yazzan. He was born in 2015, or a year after the

2014 war. This is how we date things. Once he saw a swarm of

clouds. He shouted, “Dad, some bombs. Watch out!” He thought

the clouds were bomb smoke. Even nature confuses us.

T

In summer, I drink tea with mint. In winter, I add dried sage.

Anyone who visits, even if it’s a neighbor knocking at the door to

ask about what day or date it is, I offer them tea. Offering tea is

like saying Marhaba.

They once said Palestine will be free tomorrow. When is tomorrow?

What is freedom? How long does it last?

U

It wasn’t raining that day, but I took my umbrella anyway. When

an F-16 flew over the town, I opened my umbrella to hide. Kids

thought I was a clown.

In August 2014, Israel bombed my university’s administration

building. The English department was turned into a ruin. My

graduation ceremony got postponed. Families of the dead attended,

to receive not a degree, but a portrait of their child.

V

When we moved from Cambridge to Syracuse, I looked out the

window of the U-Haul van. What a huge country America is,

I thought. Why did Zionists occupy Palestine and still build

settlements and kill us in Gaza and the West Bank? Why don’t

they live here in America? Why can’t we come here to live and

work? My friend heard me. He was from Ireland. We both loved

the Liverpool football club.

In Gaza, you can find a man planting a rose in the hollow space of

an unexploded tank shell, using it as a vase.

W

One day, we were sleeping in our house. A bomb fell on a nearby

farm at 6 a.m., like an alarm clock waking us up early for school.

In August 2014 after the fifty-one days of Israeli onslaught, the walls in

my room had more windows than when I left, windows that would

no longer close. Winter was harsh on us.

X

When I was wounded in January 2009, I was sixteen. I was taken to

hospital and x-rayed for the first time. There were two pieces of

shrapnel in my body. One in my neck, another in my forehead. Seven

months later, I had my first surgery to remove them. I was still a child.

For Christmas, a friend gave the kids a xylophone. It had one wooden

row. The bars were of different lengths and colors, red, yellow, green,

blue, purple, and white. The kids showed it to their grandparents back

in Gaza, whose eyes danced while the kids smiled.

Y

Yaffa is my daughter’s name. I put my ears near her mouth when

she speaks, and I hear Yaffa’s sea, waves lapping against the

shore. I look in her eyes, and I see my grandparents’ footsteps still

imprinted on the sand.

How did you leave Gaza? Do you plan to return? You should stay

in the U.S. You mustn’t think of going back to Gaza. Things people

say to me.

Z

When I was in the fifth grade, our science teacher wanted us to visit

a zoo, to see the animals, listen to their sounds, watch how they

walk and sleep. When I went there, they were bored, gave me their

back. They lived in cages in a caged place.

We use a zero article with most proper nouns. My name and that

of my country have an extra zero in front, like when you call

overseas. But we have been pulled down beneath the seas, do you

see what I mean?

* “Palestine A-Z” is republished here from Sumūd: A New Palestinian Reader, co-edited by Malu Halasa and Jordan Elgrably, published by Seven Stories Press 2025. The poem first appeared in Mosab Abu Toha’s Things You May Find in My Ear: Poems From Gaza (City Lights 2022). Copyright © 2022 Mosab Abu Toha.

![Fady Joudah’s <em>[…]</em> Dares Us to Listen to Palestinian Words—and Silences](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/SAMAH-SHIHADI-DAIR-AL-QASSI-charcoal-on-paper-100x60-cm-2023-courtesy-Tabari-Artspace-300x180.jpg)

In recent years I have decided to let chance guide my political and cultural perspectives. The Markaz Review which I came across by chance led me to discover this Palestinian poet. Thank you. I’m not an artist but I have often pictures in my mind that come as echos to the world distress that move me; words written by that poetry made link to these echos. Thank you very much from France. I think about Gaza… Sorry my english is not fluent !

Thank you Jordan, thank you Markaz, for bringing us Mosab Abu Toha and others of his stature as a human being. We need these reminders that the people in them are not just victims, nor statistics, but examples of the very best of the human race. Their persecution by rich and powerful assassins serves to elevate them even higher and consign their killers to the trash bin of history, where they can continue to debate the pros and cons of genocide.