George “Jad” Khoury

—Arab comics are created in the context of revolutions and wars – wars born out of dreams which, having becoming nightmares, haunt the whole of the Arab world. Is it no coincidence that comics today have become the most eloquent expression of a young generation who challenged history at the first sign of the Arab Spring, for comics are the medium that lends its voice to this generation’s ambitions, hopes and disappointments, victories, and frustrations.

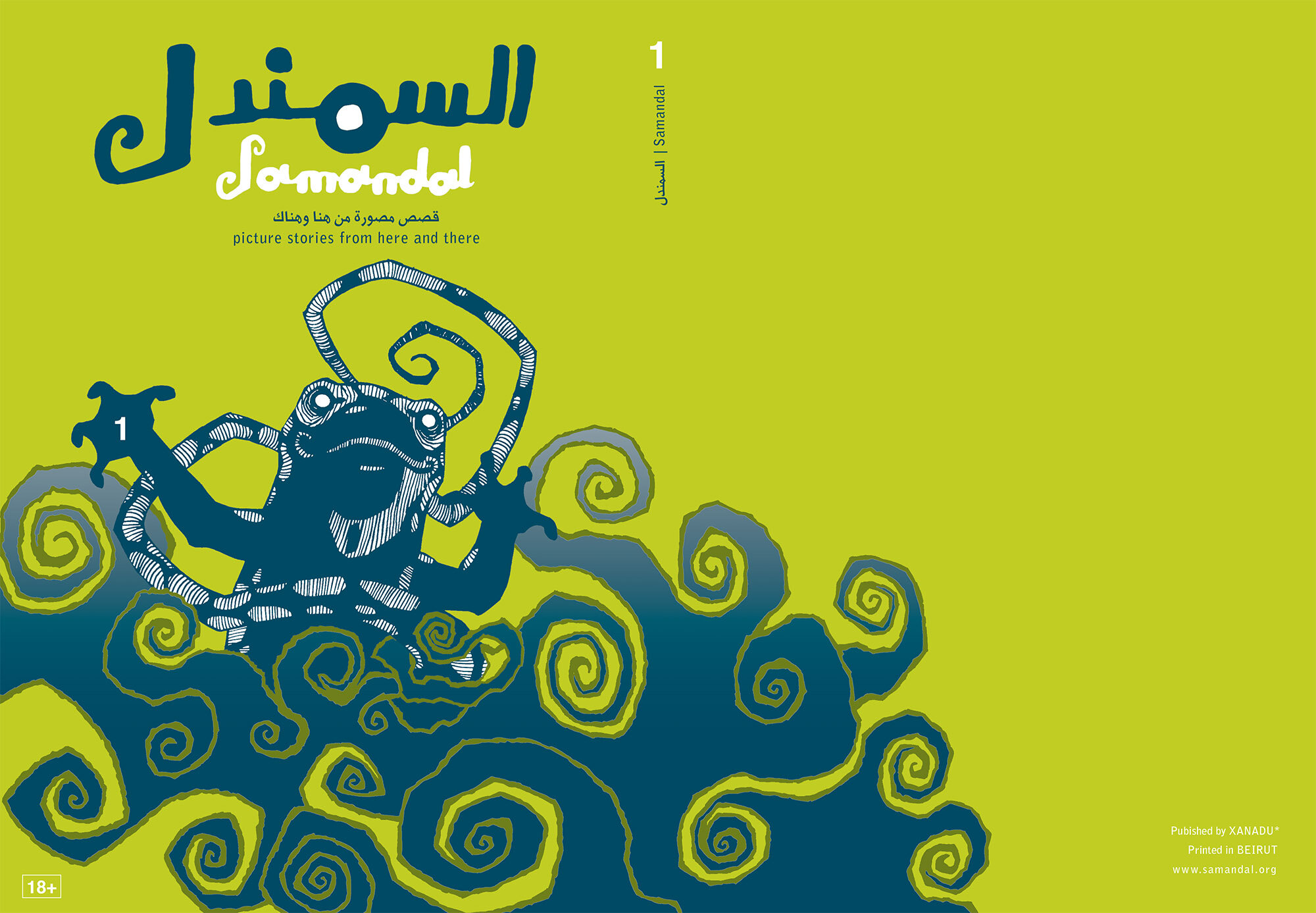

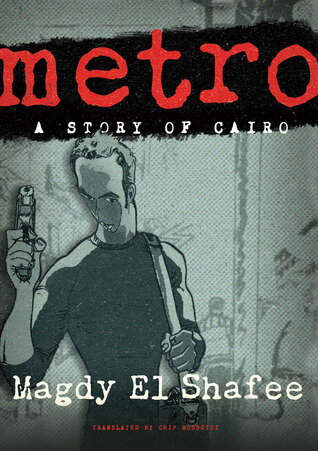

At the beginning of the 1980s, amid the civil war raging in Lebanon[1], a new wave of Arab comics was born, whose message, like a voice without an echo[2], remained inaudible. In 2007, the magazine Samandal (chameleon) took over the reins, showing us that crises and wars, even at the scale of a small country, can unleash unimaginable creativity which can burst over national borders and set ablaze every region of the world, as if it had just been waiting for this spark. Thus, Magdy El Shafee’s Metro (published in Egypt, 2008) also opened a breach, blowing a powerful gust of freedom of expression into the surrounding cultural asphyxia. The social and political importance of Metro made it the most discussed comic album in the media in Egypt, which was, at that time, suffering under the crushing weight of an agonizing dictatorship.

Collectives as a lever for change

“Whatever their form or genre, today’s comics are characterized by a freedom of expression and openness towards experimentation and personal exploration. The collectives have, since the beginning, constituted a form of rebellion against social and political hegemony and the constraints of tradition.”

Samandal, as a collective, and El Shafee, as an individual, embodies what characterizes the new wave of Arab comics, both in form and content. However, the fanzine format of the first has taken the lead on the individual practice of the second, the collective becoming progressively the “base” around which artists organize themselves. Samandal was the first initiative to adopt a collective structure, which allowed it to overcome the challenges posed by the publishing market and set itself up as a model for others to follow. By founding an organization and relying on private finances to publish its issues, Samandal found the means to guarantee its longevity. It created an independent platform dedicated to artists (mainly the founders) looking to express themselves and promote their work. Before the country’s financial collapse, the Lebanese economic system, which favors private sector initiatives, had contributed to this success.

This Lebanese initiative Samandal served as inspiration for creating the Egyptian magazine TokTok in 2011, during a period when the country was eager for change. While Magdy El Shafee’s Metro had struck at the heart of the fear surrounding the powers that be, TokTok brought together young Egyptians searching for a platform for their work. In addition to responding to a clear need on a national scale, TokTok soon became a natural “Arabic oasis,” which opened its pages to artists from all over the region, particularly in the Maghreb, benefiting from the proximity of the countries and of their respective social, political and economic structures. We cannot ignore the central role of workshops, organized abroad by TokTok and Samandal, in encouraging artists from different regions to meet and create collectives, thus cultivating spaces dedicated to freedom of expression in different countries. It is as if the collective, catalyst for the contemporary trend of Arab comics, constituted the ideal means of creating independent platforms and liberating oneself from the constraints of the publishing world.

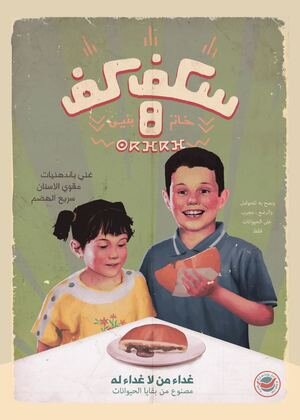

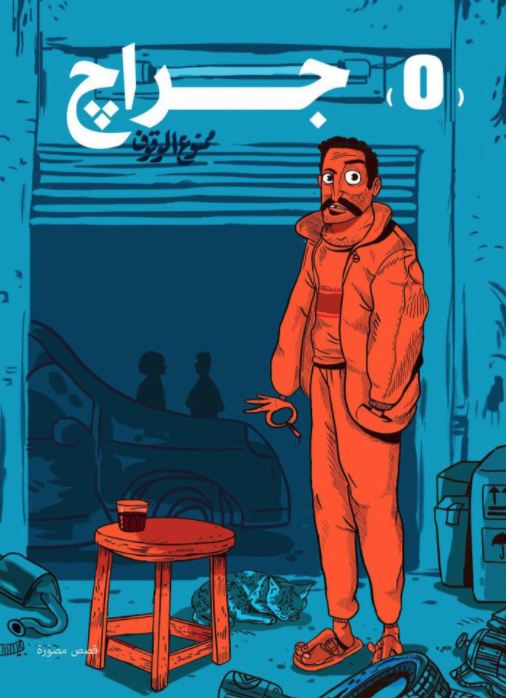

The proliferation of collectives, taking place amongst the collapse of corrupt political regimes, is in itself highly significant. It was indeed in this turbulent context that a multitude of fanzines appeared, most of which are still in print: Lab619 (Tunisia 2013), Skefkef (Morocco 2013), Masaha (Iraq 2015), Garage (Egypt 2015), Habka (Libya 2015). Other fanzines also launched, but for various reasons, did not survive, among them Al Doshma (Egypt 2011), Allak Fayn (Egypt 2016), Al Tahwila (Egypt 2012), Autostrad (Egypt 2011), Les Furies des Glaneurs (Lebanon 2011) and Al Shakmajiyya (Egypt 2014) for example.

Comic book production entered a new phase, enriched by the diversity of contributions from artists who could choose where to publish their work for the first time. At the very moment when the Arab world had become more divided than ever before, and its different regions more disconnected, comics — more than any other form of artistic expression — provided a unifying link between young artists, thanks to the network of exchanges initiated by collectives. It has since then become regular practice for a fanzine to publish the work of artists from another country, who are themselves the founders of a fanzine in their own country; or to invite an artist from a country to run a workshop somewhere else in the Arab world[3], or to take part in round-table discussions in Europe addressing contemporary Arab comics[4]. This phenomenon throws into question the individual nature of specific publications and the role of their reciprocating influences.

“I” in the linguistic mosaic

TokTok, and in its wake Skefkef and Lab619, were inspired by Samandal to self-publish and thus overcome the constraints imposed by traditional methods of publication and distribution. To do so, these non-profit, non-governmental organizations relied on alternative financial support, such as production funds provided by various agencies and institutions, for the most part European[5].

It is by their different vocations and content that these initiatives distinguish themselves. Samandal is itself an experimental platform that publishes artists from Lebanon, Arabic countries, and elsewhere in multiple languages (Arabic, English, and French). Its multilingualism reflects the cultural diversity of Lebanon. Samandal privileges experimentation over visual form, to the point, that the very nature of the comic strip is brought into question[6].

TokTok, for its part, distances itself from any elitism in form and content and focuses on themes ranging from the social and popular to the individual or personal. Its texts are exclusively written in Arabic, both classical or dialectal. TokTok uses a straightforward narrative visual language, quite removed from the experimental[7]. These elements have made it a model of inspiration for multiple publications which have followed.

Skefkef developed a form similar to that of fanzines, all in maintaining the quality, graphic design, and finish of a magazine. Each issue brings together contributions of Moroccan artists, invited to tackle a shared theme, which is most often highly pertinent to the country’s current social and cultural climate [8].

At the heart of this revival of the Arab comic is the recurring question of language, which re-launched the debate on the multiplicity of identities. If classical Arabic has traditionally dominated the literary sphere, under the influence of Pan Arabism ideology, dialects have progressively gained ground thanks to the social and political interests of the Arab revolutions[9]. The young artists who advocate using dialects proudly claim the use of “I” over “we” regarding cultural, ethnic, and linguistic diversity, which contests a unifying intellectual hegemony, of which the results are disastrous. The initiative to create these collectives is in itself a demonstration of the desire to promote the diversity expressed in their publications. The magazine TokTok and Garage are characterized by the use of Egyptian dialect and local expressions, whereas Lab619, Skefkef, Masaha, and Habka differentiate themselves by their use of other dialects — Tunisian, Moroccan, Iraqi or Libyan — to such a degree that to foreign eyes — even Arab eyes — the linguistic, regional and cultural specificities can be difficult to decipher. A look at the titles of the magazines illustrates their extreme local identity: TokTok (a rickshaw, popular means of transport in Egypt), Skefkef (a cheap sandwich, popular in Casablanca), Lab619 (referring to Tunisian barcodes), Al Shakmajiyya (a jewelry box used for make-up) and Samandal (chameleon – a nod to the diversity and linguistic and cultural adaptability of its content).

The collectives thus broke with the convention, established since the beginning of Arab comics, of choosing the title of the magazine from the panoply of names familiar to Arabic and Islamic heritage (Ahmed, Majed, Ali Baba, Samir, Sindbad, Samer, Khaled, Mahdi, etc.) – names which, above all, were systematically accompanied on the cover by a sub-heading evoking pan-Arab nationalism ideology (Oussama “The Magazine for the Arab Child”; Al Arabi Alsaghir (The Little Arab Child) “For all the Boys and Girls in the Arab World”; Ahmad “For a Muslim Generation”; Samer “For a Happy Arab Generation”).

The role of women and breaking taboos

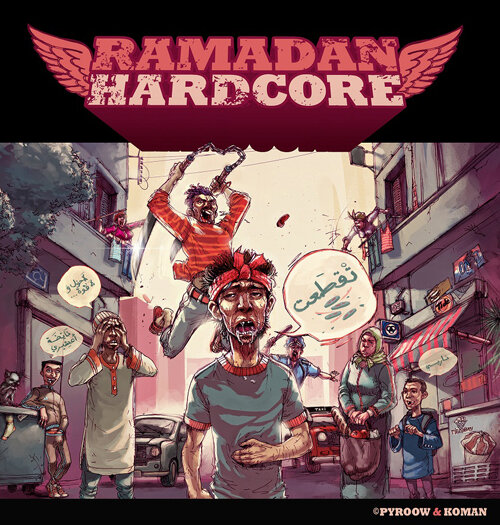

Whatever their form or genre, today’s comics are characterized by a freedom of expression and openness towards experimentation and personal exploration. The collectives have, since the beginning, constituted a form of rebellion against social and political hegemony and the constraints of tradition. They have used their publications to explore subjects long considered taboo in Arab societies, particularly those linked to sex, religion, and social traditions. Some comics even broach the following controversial topics: Al Shakmajiyya: a magazine dedicated to feminism and sexual harassment in Egyptian society; Samandal (Ça restera entre nous, [This will stay between us] 2016): consecrated its annual to sexuality and homosexuality; not to mention the comic Ramadan Hardcore by Moroccan artist Hisham Habchi. Until quite recently, these topics had rarely been tackled in a visual narrative form. Women artists were at the forefront of these first movements in the Arab world, which dared to defy the authorities and traditional orthodoxy concerning women’s rights, particularly their right to bodily integrity. The high percentage of women artists specializing in the professional comic book sector is an essential indicator of this engagement[10]. Do they, no doubt, feel more concerned than their male counterparts by the necessity of a transformative change towards individual freedom? Those who have raised and interrogated this issue are sometimes accused of “going too far,” leading to legal action against, and political censorship of, specific collectives, who have since had to publish abroad[11]. Other initiatives, born out of revolutions demanding justice, the rule of law, and liberty, have used comics as an educational tool in awareness-raising campaigns; Allak fein?, and Al-Doshma constitute prime examples.

Diversity and rebellion against the past

A burning desire for openness has left no subject or genre untouched: superheroes[12], science fiction, politics, entertainment, biting satire, current celebrities[13], or the author’s emotional state[14].

No subject is barred.

Space has unfolded where the only limit is the artist’s imagination or sensibility, far from any form of self-censorship. Another striking aspect is the almost complete absence of subjects dealing with the “glorious history of Islam”[15]. These young people are too preoccupied by the present moment and wish to break with the past; they rebel against it. This likely explains the visual aesthetic inspired by European comics, Japanese mangas, or even American animated television series[16]. Only certain Egyptian artists inscribe their work in the local visual heritage, notably made up of caricature, which forms an essential part of collective memory in Egyptian society. It has become common to see artists master multiple techniques, using a mixture of caricature, illustration, comics, and graffiti (Mohamed Andeel, Makhlouf, and Ganzeer, for example, but above all the Moroccan artists in their conquest of urban walls).

In terms of form, these magazines restructured their editorial content and sections to reflect their objectives and values better – incorporating another layer of diversity. Thus the traditional didactic structures, which had dominated magazines for children (each distinguishing itself from the others only by the ideology it propagated), wholly disappeared. Samandal created mirror pages that invite the reader to turn the magazine in different directions depending on the alphabet used, Arabic or Latin. TokTok replaced sub-sections with profiles of famous artists, concluding by the comic remark (Made in Egypt) or by a more visual presentation. Lab619 prefers to present the artists’ pages with no introduction and does not give importance to the change in the reading direction when the stories are written in Latin script. Skefkef, on the other hand, interlaces its illustrated pages with short stories, emphasizing that the written text is just as important as the visual aspect. It has also provided musical elements to accompany its issues[17].

However, these magazines are missing an important feature of modern comics; their long series of graphic narratives. The classic “To be continued…” is almost totally absent from all of these new magazines, perhaps because their authors cannot be sure that another will follow this issue… Contributions are often limited to concise ideas and short stories without long narratives or continuity between issues[18]. As if the artists, in the context of revolution, wanted to position themselves in the present moment, that is, to focus our attention on their personal torments before moving onto something else. This point deserves to be highlighted since the region is known for its heritage of oral narrative and never-ending stories, traditionally passed on from generation to generation (such as The 1001 Nights, The Saga of Banu Hilal). Graphic novels in Arabic are scarce since the publication of Metro, except for Murabba wa Laban [Jam and Yoghurt] by Lena Merhej; A City Neighboring the Earth by Jorj Abou Mhaya, Ayalo by Mustafa Youssef, and Al Tahadi [The Challenge] by Omar Ennaciri. Several others might never have seen the light of day were it not for western publishers who brought them out in their respective foreign languages (Zeina Abirached, Michèle Standjovski, Hamed Sulaiman, Barrack Rima, Kamal Hakim, Ralph Doumit and the publications of ALBA – Lebanese Academy of Fine Art[19]).

Developing professional expertise

The significance of this current wave of Arab comics lies in the fact that it does not find its roots in the impulsive fantasies of a handful of young artists, who, burning with a desire, would readily seek out other horizons once their objectives are achieved. These young, contemporary artists are fully aware of the social and political situation which surrounds them. Most have experienced — and some, in a very active way — opposition movements against the repressive and corrupt systems in their countries. Therefore, with full awareness and maturity, they have taken on these new artistic approaches, following a model which they intend to make last. Here lies the importance of workshops organized in the hope of reinforcing the professionalization of the domain, a condition sine qua non for its survival. These workshops enable artists to meet and create spaces for discussions, debates, and sharing ideas, constructing a framework of shared references and ongoing communication that promotes solidarity and cooperation. CairoComix (the comics festival born in Cairo, 2015) is the most emblematic of these local and international gatherings. It plays a pivotal role in nurturing this new movement and provides a solid platform where artists can exchange experiences, discuss ideas and promote their work.

This significant turning point in the approach towards comics was accompanied – and in some cases preceded – by the introduction of university courses in comics, together with a growing interest in academic research in the field[20].

The book or the “lost market”

While the collectives successfully established a solid basis for creating a new genre of adult comics through their fanzines, it was not the same case for graphic novels, which continue to rely on publishing houses and conventional distribution networks. El Shafee’s Metro was an unusual phenomenon and unheard of since. Its publicity and media campaign played a significant role in its distribution in the Arab world, despite its being banned. Its censorship resulted in the opposite effect intended, leading to broader publicity on a regional and a national scale. Nevertheless, this also opened the eyes of the authorities to the significant potential of this new medium, thus putting publishers under even more pressure. Other Arab artists, who are just as able with word and pen as El Shafee, have only published in foreign languages[21]. After a burgeoning period in the broad regional market, publishing has progressively shrunk to national borders. The absence of local publishers who specialize in the production of comic book albums is itself a factor that makes it difficult for projects to develop insofar as the publishers do not benefit from private investment, unlike collectives.

In this context, digital mediums have presented a vital alternative to conventional means of publication and distribution, not to mention providing a way of navigating increasingly intense censorship. In addition to using digital media, which aid the transmission and distribution of their work in faraway places, artists also use social media to create virtual platforms to “distribute the forbidden.” The most pertinent example remains the collective of Syrian artists who, pursued and menaced with death threats by the Assad regime, distributed their work on a Facebook page called Comic4Syria. This page is an irreplaceable, creative source of documentation on the civil war in Syria, which has already caused the death of more than half a million persons. For obvious reasons, the contributors, unfortunately, are obliged to remain anonymous. The Moroccan author Hisham Habchi, who published his comic series Ramadan Hardcore during Ramadan, was able to avoid censorship thanks to the Internet. The situation is similar in Egypt, where a large number of writers and artists are on trial. Many local organizations are ordered to reduce or cease their activities on the pretext that they receive foreign funding to serve foreign interests or leak sensitive information (including statistics on human rights, for example!). Even worse, censorship in Arab countries is not solely initiated by state initiatives: it runs much deeper into civic and religious institutions as was seen, for example, with Samandal, which was the subject of legal proceedings for “offense to religion,” after the Catholic church complained.

Whether or not the future for comics remains bright depends on you; comics, like books, need readers.

[1] In 1980 the first comic book for adults was published: Carnaval (Jad), followed by Abu-Chanab (1981), Alf Leyla wa Leyla (1982) and Sigmund Freud (1983). This path lead to the collective JadWorkshop (1986) which included: Lina Ghaibeh, Wissam Beydoun, Edgar Aho, May Ghaibeh and Shoghig Dergoghassian. The album Min Beirut (1989) was the last publication of the group, and the collective came to an end after a final exhibition, Out of Communication, in 1992.

[2] Mazen Kerbaj is the only exception in terms of consistent continuity, although his production is primarily in French. Kerbaj remains a ‘lone wolf’, unassociated with any particular collective, and is the most prolific author on the Lebanese scene. His best known album in Arabic is hazihi al-hikaya tajri (Dar-Al-Adab, 2010).

[3] Samandal, TokTok and Skefkef are the most active in this domain.

[4] The 2015 Barcelona platform brought together artists from four collectives: Samandal, TokTok, Skefkef and Lab619. This meeting was preceded by a similar, larger, one at Erlangen in 2008, and we should not forget the influence of the round tables established in 2015 by CairoComix.

[5] French, German and Italian cultural centres have contributed to the funding of Samandal (Lena Merhej, 2015, “Meeting in the Land of 1000 Balconies”, La Capella, Institut de Cultura de Barcelona). TokTok is supported by funding from the European Union and Skefkef is aided by local donors (interview with Salah Malouli of Skefkef and Mohamad Rahmo, founder of the cultural agency ‘Madness’, 2017).

[6] “ (…) [The story must be beautiful, the drawings aren’t that important…]” (Lena Merhej, 2015, “Meeting in the Land of 1000 Balconies”).

[7] “If an artist puts forward an experimental work, I tell him go to Samandal (Mohamad Al-Shinnaoui, 2015, “Meeting in the Land of 1000 Balconies”).

[8] Skefkef underlines the cultural and ethnic diversity of Morocco where Amazigh (Berber language), was recently recognised as the second official language. (Interview with Salah Malouli, Casablanca, July 2017).

[9] It is important to note here that all comics in the region were published or controlled by state-run instituions. The example of adult comics using Arabic dialect, in the 1980s in Lebanon, was an exception.

[10] A quarter of the Skefkef and more of Samandal artists are young women. There are almost twice as many women solo authors of albums as men, among them: Zeina Abirached, Lena Merhej, Joumana Medlej (Lebanon), Zineb Benjelloun, Zeinab Fassiqi (Morocco), Noha Habaieb (Tunisia).

[11] Samandal chose to focus its latest issue on sexuality in France, as a co-production with Alifbata (Ça restera entre nous, Alifbata/Samandal, 2016)

[12] The series Malaak by Jouman Medlej (Lebanon 2007) and 99 about Islamic super heroes by Nayef Moutaweh (Kuwait 2006).

[13] The character of “Al-Sayess” by Mohamad El-Shennawy, mascot of the TokTok magazine.

[14] The Samandal artists are pioneers in this, as they don’t mention or make reference to the ‘Arab Spring’, whilst the others began in revolutionary circumstances and embraced the activism that went with them.

[15] Morocco remains an exception with the series Tarikhuna, in Amazigh.

[16] In Morocco for example, today’s young artists grew up reading comics like Spirou, in the absence of any local production. (Interview with the Skefkef collective, 2017). In other publications, the influence of mangas and cartoon series broadcast on the Cartoon Network is clear.

[17] Skefkef’s formula is based on an artists‘ workshop in Casablanca who come together to work on a particular local theme, as well as calling on alternative music bands to work on the same theme and take part in the publication.

[18] Migo’s Ya’ jouj wa Ma’ jouj is an exception in TokTok (issues 7-14).

[19] The Lebanese Academy of Fine Art (ALBA) has been the training ground for generations of artists who make up the majority of potential actors in Lebanon.

[20] L’Insitute Nationale des Beaux-Arts (Tétouan – Morocco), LAcadémie libanaise des beaux-arts – Alba (Lebanon) are the first, and maybe only, academic insitutions to propose a full academic program in this domain. The Alba has trained generations of Lebanese illustrators, which form the majority of comics artists in Lebanon. The Mutaz and Rada Sawaf Arabic Comics Initiative of the American University of Beirut, founded in 2014, plays a pioneering role in the domain of academic research in the comic genre in the Arab world, and also supervises the annual Mahmoud Kahil Prize for artists working in comics, caricature and illustration.

[21] Mazen Kerbaj, Zeina Abirached, Michèle Standjovski and Sleiman El-Ali for example.

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)