The perception of deserts as spaces devoid of life has justified exploitation and experimentation, yet deserts could push our thinking beyond ordinary notions of space and place.

Brahim El Guabli

The desert made global headlines twice this past summer. Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer was released in July, recounting the story of the man who turned the New Mexico desert into a testing ground for the first nuclear bomb. Despite its resounding absence from the movie’s script, the desert was essential to the Manhattan Project and its devastating grand finale. Two months later, Burning Man revellers were caught in the midst of a rain storm on the Indigenous land of Black Rock City in the Nevada desert. The experimental spirit of both the Manhattan Project and Burning Man takes the supposedly empty desert space as a site for gargantuan undertakings.

Unlike the desert of Oppenheimer and Burning Man, my desert is inhabited and lively: a civilization of its own.

These uses contradict my understanding of the desert as a home: a place of origin and an indigeneity grounded in its relationship to place rather than space – unlike geometrical space, places have affective and emotional importance. My mother is Black and my father is Sahrawi, but I was raised among Imazighen (Berber people). My family’s identity was shaped by memories of desert origins and multiple histories of passage between sub-Saharan Africa and the Maghreb. Processing my own indigeneity and my connections to land and people was further complicated when reading Nazīf al-Hajar (The Bleeding of the Stone) and the two volumes of al-Majūs (The Fetishists) by Libyan novelist Ibrahim al-Koni, as well as Mudun al-milh (Cities of Salt) and al-Nihāyāt (Endings) by exiled Saudi novelist Abdelrahman Munif. Unlike the desert of Oppenheimer and Burning Man, my desert is inhabited and lively: a civilization of its own.

There is no dearth of deserts in the world. Desert landscapes occupy a third of the Earth’s surface and receive an average of 250mm of rainfall a year. Deserts are not all, unlike the ubiquitous images of sand dunes, nicely rimmed, dreamy ergs (seas of sand). According to National Geographic, only one in five deserts are sandy. The others are made of regs (pebbly plains), wadis, ravines and mountains. This diversity of landscapes has fostered a biodiversity adapted to drought and drastic temperatures, scorching hot during the day and freezing cold at night. Deserts foster the growth of a unique life that encompasses plants, including medicinal ones such as artemisia and colocynth, as well as insects and mammals; they are restorative habitats for seeds and insect spawn, which reappear, even years after they were last seen, when rain falls.

In June 1927, botanist Walter Tennyson Swingle, working for the US Department of Agriculture, was invited by the French colonial authorities to the palm groves of the Moroccan desert to participate in an inquiry mission. A fungal disease, bayūḍ, had struck palm groves in the date-rich towns of Figuig and Boudenib, and Swingle was to help the French scientists investigate the nature of this illness. He snatched this lifetime opportunity to set foot on what he called “the single date planting place in all Africa.” In addition to learning about the pernicious illness that made palm trees wilt and wither, he observed how local people tended to the palm groves, pollinated and cleaned the trees. A tribal leader he met in Boudenib gave him 11 palm offshoots of the medjool type, which he sent to Washington DC. The offshoots were moved for a two-year quarantine in the Mojave Desert before they were planted in California. A hundred years later, the nine offshoots that survived are the living ancestors of thousands of medjool palm trees in the California desert.

Swingle’s stint in Morocco speaks to a long tradition of extractive practices that unfolded in deserts and which encompassed people, animals, plants, minerals and oil. Between 1500 and 1900, millions of people were dislocated from the Sahara to be enslaved in North Africa and the so-called New World. The French colonial literature produced until the 1950s is replete with designs to extract labour from both nomads and sedentaries in Saharan communities. Accounts of French occupation reveal that camels were used for hunting moufflons, gazelles, tigers and rabbits. Mark Twain’s book Roughing It from 1872 contributed to the hatred of – and later attempts to exterminate – the coyote and, as author Forrest Bryant Johnson recounts, the US government was at the time importing camels and their trainers from Egypt to use them in its ongoing warfare against the Mormons and the Native Americans in Utah.

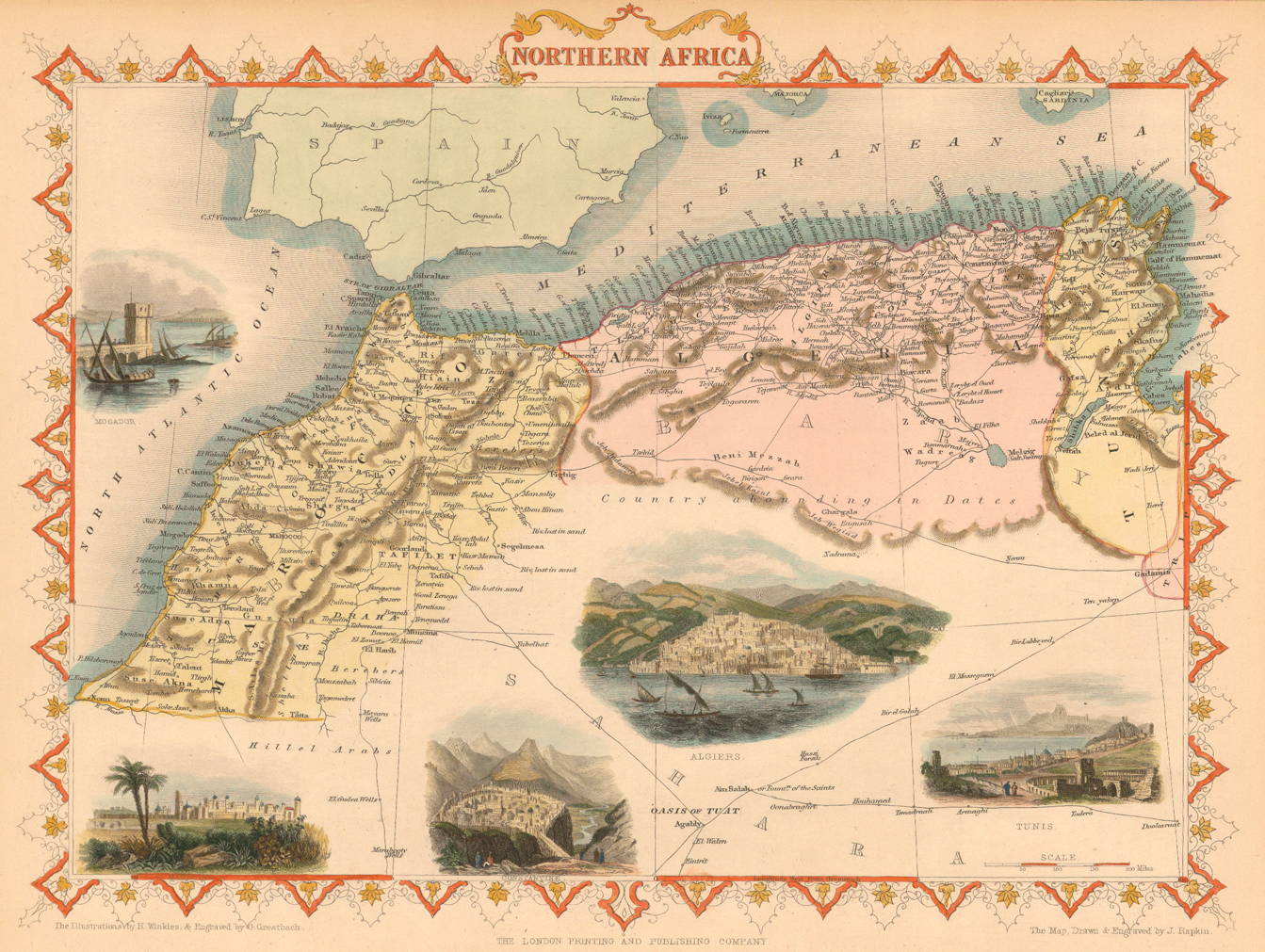

These extractive and experimental endeavours are the product of what I call Saharanism: a pervasive ideology that universalizes deserts, anchoring them in the popular imagination as empty, exploitable and interchangeable spaces. Since they are seen as res nullius (property of no one), states, militaries and venture capitalists lay claim to desert sites for a host of purposes. Although ubiquitous, this phenomenon has remained unnamed and its implications, both discursive and real, have so far eluded critical attention. I propose to call it experimental Saharanism. Ranging from agricultural production to industrial infrastructure, from nuclear testing to solar energy harvesting, and from new technologies to entire new cities, experimental Saharanism benefits from deserts’ presupposed emptiness. When conceptualized as desolate, devoid of life and even dangerous, deserts offer unlimited tracts of disposable land that can be used by self-serving regimes of governance. Things as seemingly benign as the pictures that visitors take of sand dunes and camels are inherently framed by a long tradition of more overtly violent Saharanist imaginaries.

The imperialistic construct of deserts as wasteland and wilderness is codified in language. The French dictionary defines the désert in terms of uninhabitedness, void and lack of human activity. Like in English, it is associated with dullness, nakedness and dreariness. By contrast, the word ṣaḥrā’ (desert) is not the only word used in Arabic or Amazigh (indigenous languages) to describe this landscape. Bādiyya, barriyya, baydā’, sabsab, arā’, flāt, mafāza, fayfā’ are used, with nuance, depending on the topography or the ‘sandiness’ or ‘stoniness’ of the place. While the English and French meanings that stem from the word ‘desert’ have no equivalents in the root ṣ-ḥ-r, this root allows us to generate several verbs and verbal nouns that are closely related to the desert, including cooking (ṣaḥara), leaving land unattended, and desertifying. The Arabic origin of the term does not point to emptiness at all; it rather emphasizes an interaction between different elements. The desert is not really deserted. It is a locus for the millennial production and transmission of knowledge, traditions and know-how.

Among the Amazigh, in Tamazight, the desert is described as ivar, anezraf, anezruf, tanzruft, tama, asnzruf, tiniri and tinariwin. Importantly, tinariwin means deserts in plural. Instead of being a singular void, deserts, by virtue of their plurality, are full, both materially and immaterially: places that are constantly filled with other forms of existence, including spirits and ghosts.

The transformation of deserts is always tangled with human interest and aspiration to domination.

As languages of nations that never had any indigenous deserts of their own, English and French foreground the wasted nature of the uninhabited land, which then serves as a springboard for their reuse or mise en valeur (read: exploitative development). From 1900 to 1962, French car makers such as Renault, Berliet and Citroën tested the mettle of their creations in the Saharan sands. No wonder then that the recycling of colonial clichés that stigmatised specific areas as ‘the desert of deserts’ gained currency simultaneously with the car industry’s attempts to penetrate these spaces. As Mériem Khellas reveals in L’Afrique de Berliet, Berliet even designed a powerful, six-wheeled truck named Gazelle and endowed it with a Magic engine specifically designed for the desert at a time when France’s military and economic existence in the Sahara was gaining strategic importance. In the US, since 1953, several car companies have owned over 38,000 acres in the American West to test their cars.

The transformation of deserts is always tangled with human interest and aspiration to domination. In the 19th century, France and Britain undertook trans-African train projects to link their different colonies. Beyond facilitating extraction of agricultural and mineral resources available in their colonial dominions and speeding up export of their domestic products to the colonies, a train traversing the desert was seen as a demonstration of human victory over nature. While France’s early prospects of a trans-African train were cut short by the Tuaregs’ murder of Colonel Flatters and the insolvency of the project, even after France dominated the entire Sahara by 1900, Britain built railway infrastructure to link its colonies from Egypt to South Africa – today, only a small portion of the initially envisioned 10,500km is in operation. Beyond their economic goals, these projects involved a great deal of testing existing technologies or imagining new ones to overcome the challenges posed by the desert environment. Charles Tellier, the inventor of the refrigerator, went as far as to suggest the construction of a train that would be powered by desert sun to ‘pacifically’ colonize West Africa. Beyond business interests, the collaboration with different branches of government required by these projects reveals that experimental Saharanism is not the province of individual dreams, but rather the realm of statal fascination with deserts, and the desire to transform them.

Experimental Saharanism harnesses architectural and technological advancements to transform the supposedly hostile desert landscapes into human-friendly environments – hence obliterating the desert condition. The looming changes Mohammed bin Salman’s Neom is bringing to north-western Saudi Arabia are perhaps the most vivid contemporary example of this phenomenon, powered by climatic engineering and computer-assisted simulations. Already in 1882, as historian Philipp Lehmann examines in Desert Edens (2022), French military geographer François Élie Roudaire endeavoured to construct a mer intérieure (inland sea) in the chotts between Algeria and Tunisia. This bold and colossal project garnered the support of Ferdinand de Lesseps, the architect of the Suez Canal. “It was like wildfire, and enthusiasm broke out,” wrote geographer – and colonialist – Henry Chotard at the time. “We saw under the beneficial influence of these waters borrowed from the Mediterranean the appearance of the country change as if by magic. The sands became fertile lands, which were covered with woods, meadows, crops; the few villages were replaced by numerous and well-populated towns with industry and commerce.” Roudaire’s inland sea would have transformed not only navigation between Algeria and Tunisia but also the desert’s ecosystem, imposing a new fauna and flora on the Sahara. For Chotard, the “Mediterranean entering the Sahara” was a triumph over nature, an event worthy of global proclamation. Luckily, the project was too costly to be pursued.

The environmental consequences of an inland sea in the Sahara would probably have been even more devastating than the Salton Sea disaster, an artificial lake in the Colorado Desert created in 1905, when Colorado River floodwater breached an irrigation canal under construction. After being a popular holiday destination, the body of water is now drying up, and the increased salinity and pesticides from the agricultural run-off are disrupting the entire ecosystem. As more shoreline is exposed, chemical-laced dust will be blown by the wind into neighboring communities. It is not difficult to imagine the number of oases an inland sea in the Sahara would have drowned, and the number of swamps it would have created.

Experimental Saharanism stops at nothing to mobilize deserts for its purposes; the harsh conditions made them suitable sites to test and train human capacity to fight. Faced with the Nazi occupation of North Africa in 1942, General Lesley McNair issued an order for the creation of the Desert Training Center (DTC), where American soldiers would prepare for desert warfare in a “recreated Sahara” spanning an area of 46,000km square. As historian Sarah Seekatz explains, the proving ground also enabled the testing of military equipment and camouflage techniques, and prompted developments for “better maintenance of tanks and other vehicles, and even new supplies like dust respirators.” Southern California and western Arizona are not the Sahara — neither their topographies, demographies, languages, nor their biomes resemble each other — yet Saharanism sees deserts as spaces that can stand in for each other, where similar experiences can be had. As early as 1908, political economist Paul Leroy-Beaulieu likened the “steppe of hunger” in Turkestan to the “land of thirst” in the Sahara. This monolithization of deserts becomes even clearer after the advent of the nuclear age in 1945.

The United States’ construction of a nuclear bomb transformed the nature of experimental Saharanism and changed deserts in unprecedented ways. Although it was first developed in France and Germany, atomic research was perfected in the US; the Manhattan Project unleashed the energy enabled by atomic fission and weaponized radiation for purposes of mass destruction. The US government chose Los Alamos in New Mexico to test the first nuclear bomb in 1945; four years later, the Soviet Union opted for the steppe of Semipalatinsk Test Site in Kazakhstan. The UK conducted its own tests in Australia’s Maralinga in 1956, while France used the Sahara in the 1960s. Given its inherently deadly nature, nuclear experimentation placed desert emptiness as a sine qua non for its existence. Tanezrouft was “reputed for the absence of any life in the immense spaces that separated Reggane from Tessalit,” French General Charles Ailleret writes in his memoirs to justify his country’s choice of the Sahara to detonate its first bomb. Ailleret omits to say that this region witnessed bloody battles between French soldiers and the Tuaregs, such as the 1917 Battle of Tanezrouft.

The emptiness Ailleret refers to was propagated by geographer Émile-Félix Gauthier, a University of Algiers professor and powerful colonial academic whose ideas about the Sahara influenced generations of French officials. In 1923, he for instance wrote that Tanezrouft “designates the part that is entirely dead of the Algerian Sahara.” This cliché would be particularly recurrent in the 1950s, when it was recycled by French bureaucrats, politicians and army officers. Testing atomic bombs also required building laboratories and facilities and, unlike agricultural or infrastructural projects, radiation has a deadly lifespan that can last for thousands of years. Sites of nuclear experimentation continue to impact populations across the globe today. As Samia Henni reminds us in Deserts are Not Empty (2022), “architecture is not only what is designed and built but also what is indebted, destroyed, dismantled, contaminated, displaced, buried, unearthed and wasted.”

The rise of cybernetic and drone technologies in the 2000s has brought a different type of experimentation into the desert. As recently as 2017, the National Public Radio (NPR) reported that US soldiers in the Mojave were “testing how much [cyberwarfare] know-how can be put in the hands of troops on the ground who may have to fight someone with intense cyber capabilities like the Russians or Chinese.” In 2018 and 2020, the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization and the Mauritanian government flew drones to fight against locusts, seeking to confirm drones’ ability to function in different desert conditions. A similar operation was carried out in Oman this year. While drones can detect locusts in inaccessible areas and help experts prevent them from damaging crops and trees, the less visible aspect of this intervention is that the drones’ durability and their ability to withstand heat and collect data are also being tested. Several human rights activists have drawn attention to the threats that drones can pose if used to monitor migrants – including those who hail from sub-Saharan Africa and have to cross desert lands to reach the Mediterranean.

As a celebration of experimental Saharanism, Oppenheimer is reflective of the reality that gadgets, measurement charts and performance reviews are seen as more important than the desert itself. The most curious thing about experimental Saharanism is the absence of scientists from public debates about the experiments they conduct — as if science became the province of politicians and bureaucrats. Deserts are prime examples of the “dark geographies” that American geographer Trevor Paglen writes about: unmarked spots on a map where clandestine operations can take place, drawing connections between geography, secrecy and the impunity that stems from unbounded power.

And yet nothing is stable in the desert. The wind moves sand dunes, bones, landmarks. Roads get buried, train tracks get lost and paths do not survive the next gust of wind. The desert lays bare everything, but it also summons the multiple forms of generosity that adhere to an ethics of survival and to notions of ecological care. Studying deserts proactively pushes our thinking beyond the ordinary notions of space and place. My students always express their surprise at how much they did not know or how much their ideas about the place were informed by the very misconceptions we aim to deconstruct. Deserts are places with a history and, despite the reductive acts and discourses of experimental Saharanism, they are also open to a possible, different future.

An earlier version of this essay appeared in Architectural Review and is published here by arrangement with the author.