“What’s more useless than a bridge leading nowhere?” asks Yousef H. Alshammari, on Kuwait’s nation building.

Youssef H. Alshammari

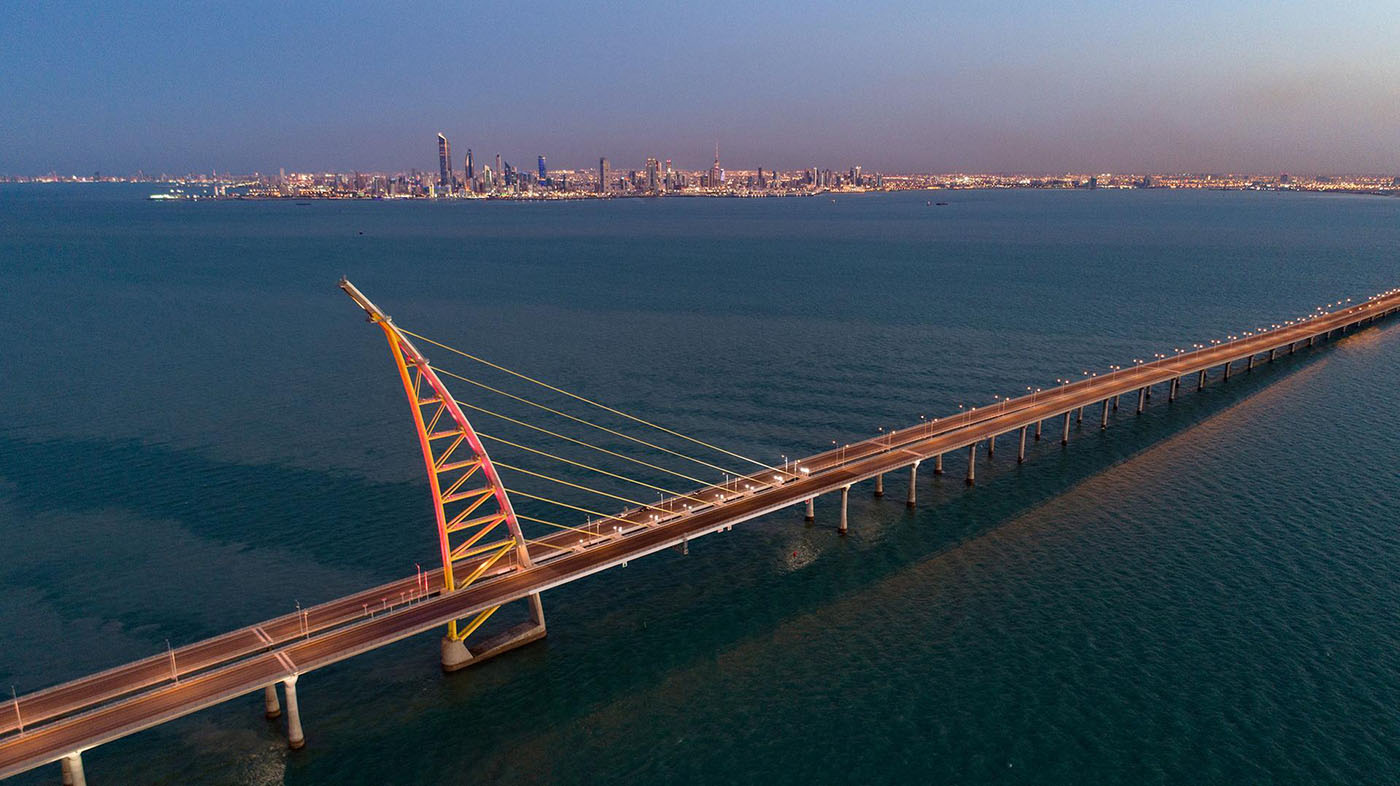

On a cold December day in 2021, Kuwaiti police officers charged towards the scene of a reported car crash on the Sheikh Jaber Al-Ahmad Al-Sabah Causeway, known locally as Jaber Bridge. The horizon ahead held nothing but sky with a creeping expanse of sand visible behind the bridge’s metallic towers and cables. Underneath it, a gray sheen of oily pollution covered the blue gulf waters, as always dotted with luxurious cabin cruisers and distant cargo ships. When officers arrived, they found a single vehicle stopped near the railings and one young man frantically overlooking the parapets to the Bay of Kuwait below, searching for a glimpse of the body of his friend, 25-year-old Mohammad Al-Fadhli. The two friends had both been stateless — known as “bidun” — and, frustrated by the precarity of such an existence, they had cosigned a deadly pact. When they arrived at the remote middle of the bridge, the friend had hesitated. Al-Fadhli did not. He jumped to his death.

Two months before Al-Fadhli’s demise, a male Indian migrant had similarly jumped from the Jaber Bridge, only then a civilian boat had come to his rescue. This July, two Kuwaiti women attempted the same within a 24-hour period. Only one survived. Dubbed by some locals as “suicide bridge,” it has become the place where those who endure all the city’s sins — statelessness, predatory labor conditions, gendered discrimination — go to end their suffering.

Jaber Bridge was originally built as part of Kuwait’s Vision 2035, a state initiative aimed at transforming the country into a regional hub for finance, commerce and culture. The construction of the bridge had also been funded by the Belt and Road Initiative, China’s global soft-power plan to invest in other nations’ infrastructure. Lauded as one of the world’s longest bridges — it spans a stretch of almost 50,000 meters — Jaber Bridge shoots off a smaller link connecting Kuwait City, the skyscraping capital surrounded by urban provinces running along the coastline, to Doha — not Qatar’s capital but another nearby urban area. The central causeway, the main reason for a near $3 billion expenditure, connects the capital to a couple of incomplete artificial islands, joins with an incomplete road to Bubiyan, Kuwait’s largest of its natural islands, and finally arrives at Subiya, a natural reserve of land empty of all but sand.

In the ‘80s, after suffering a hefty stock exchange crash, parliamentary dissolution and sectarian anxieties, amplified by no less than Kuwait’s open financing of Iraq against Iran in an eight-year war, Kuwait began to envision a different future with a new city to anchor it. The first Gulf War brought further debilitation and paranoia arising from the backlash of having funded Saddam Hussein’s previous war only to later suffer his invasion, which somewhat derailed the scheduled arrival of that future. But in 2017, the Kuwaiti government finally ratified a path forward with Vision 2035, solidifying a plan for a “new Kuwait” to come. Two years later, on December 15, 2019, Jaber Bridge opened to the public and Kuwait’s vision attained some clarity — until people realized that the bridge in fact led nowhere.

Media portrayals of Kuwait often paint it as an oil-rich country roughly the size of New Jersey. While the former is true, the latter’s geographic comparison is comprehensible to a US audience only. On a map, Kuwait looks like a silhouette of a falcon’s head pointing eastward with its beak gaping open, swallowing the gulf water. On its lower beak, its mandible, sits Kuwait City, and Jaber Bridge is a string of metal running northward to the maxilla, the upper beak, where the nowhere of Subiya still awaits the construction of its future city.

Subiya is the prophesied home of Kuwait’s Silk City — or Madinat-al-Hareer, its name meant to evoke the splendors and commercial riches of the ancient Silk Road, in the hopes that the new city would become its own mighty financial center. Its concept predates the blueprints of both present-day Dubai and in fact Vision 2035 itself, though it was subsequently adopted as a central element of the project. Although its complementary elements, like the artificial islands surrounding it that were built to host future tourism projects, have been minimally assembled, Silk City remains only a concept, its grounds unbroken. As such, Vision 2035 has so far presented us with only a bridge connected to nothing.

The day Al-Fadhli flung himself down to Kuwait’s lowest geographic point, I was at its highest artificial point. I was a full-time corporate communications officer often writing press releases for a multi-million-dollar conglomerate lodged on the 72nd floor of the country’s tallest skyscraper, Al Hamra Tower. Sitting across from a panoramic view of Kuwait City with Jaber Bridge in sight, none of us really believed the shiny promises we were paid to write down. My old line manager once told me: “Make sure you mention that all we’re doing is in alignment with the day that’ll never come,” teasing the lack of faith in Vision 2035’s arrival. As a journalist often covering politics and a writer who’s all too sensitive to the madness around me, selling the ideas of a shiny city to come paled in comparison to seeking out the underbelly of Kuwait City, my city.

“Fifteen minutes from Kuwait City to Silk City” is one of the oft-repeated selling points of Vision 2035. Official state plans outline seven focal points for a new Kuwait, with a comprehensive list of targeted goals ranging from better mortality rates and more scientifically-advanced education, to environmentally friendly and charitable initiatives. This great move away from oil also promises greater reforms to come, from loosening the bureaucratic grip on government affairs to less state oversight censoring the arts. Though vague and largely undefined, these visionary goals to be executed by the state and funded by the private sector, point to a Silk City arising from the collusion between the government and the elite. Unlike the relatively more organic formation of Kuwait City, the deals struck to support Vision 2035 reveal a more calculated approach: to build another city that further erases the disempowered.

A number of people, estimated today to be in the hundreds of thousands, fell through the abyss between them, creating both a conundrum of statelessness still unresolved and a pervasive mythology of national identity.

And perhaps no one is more disempowered in Kuwait than those who live in the country but don’t enjoy the benefits of its citizenship. One of Kuwait’s recurring debates revolves around the inflammatory question of who is Kuwaiti and who isn’t. The answer to that is closely related to the historic growth of Kuwait City and the development of invisible yet no less violent barriers of class, determining just who receives political power and who’s excluded from accessing it. Kuwait’s rising petroleum industry coupled with liberation from British rule paved the way for a previous fort to grow into a city, and then that city into a city-state. Laced across the coastline, stretching from Kuwait Bay and down the falcon’s neck, the rise of a provincial urban landscape centralized Kuwait City’s power further. Regardless of their ethnic backgrounds, most of its denizens flocked closer to the capital.

While droves of would-be citizens came closer to the city, helping usher in a modern country, not all groups of people were embraced into the fledgling nation-state. According to Vision 2035, Jaber Bridge’s smaller offshoot is supposed to transport commuters to a future global port beyond Doha. But once again, a more dismal reality lives behind Vision 2035’s talking points. For that offshoot of Jaber Bridge in fact takes us to the Al-Jahra governorate, another type of nowhere. Or at least, a city that houses no one according to Kuwait’s legal definitions, given that most of Al-Jahra governorate’s people are barred from citizenship.

The reasons for this are two 1959 laws — the citizenship law and the resident law — with contradictory articles. A number of people, estimated today to be in the hundreds of thousands, fell through the abyss between them, creating both a conundrum of statelessness still unresolved and a pervasive mythology of national identity. The citizenship law’s second article states that anyone born to a Kuwaiti father, whether inside or outside of Kuwait, is a citizen. The resident law’s 25th article holds that Bedouins and tribe members regularly traveling into and out of Kuwait — most of whom are currently bidun — are exempt from residency. The two laws are simultaneously active in the confines of Kuwait’s borders. Though effectively, they are applied only in the confines of Kuwait City, alienating Jahra and its people in the process. As the nation trod forward with the formation of a central city, so too did it develop a central identity: the closer you were to the city, the truer your roots.

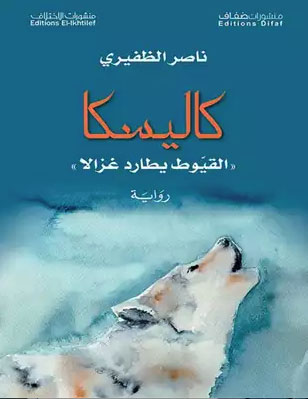

Kaliska is the name of the second novel in Nasser Al-Dhafiri’s Jahra Trilogy, which posthumously collects the late and previously stateless author’s most popular works. The trilogy’s name refers to the home wherein most of Kuwait’s bidun population live, and Kaliska, like much of Al-Dhafiri’s fiction, details the compounded burdens of statelessness and casts an illuminating focus on Kuwaiti identity politics. Also emphasizing his own position as a “Kuwaiti-Canadian author” after a successful, yet much lamented, migration, Al-Dhafiri’s characters often ache doubly. His works express a longing for Jahra to be included in Kuwait’s national identity, but at the same time acknowledges that the scars from the historical amputation that is statelessness run too deep.

Kaliska relates the story of Mohammed Al-Awad, a humble child from a bidun family who gains citizenship when his paternal uncle claims guardianship over him, after Mohammed’s parents suffer a fatal car crash. Mohammed would’ve then remained a citizen if not for later falling in love with Rasha Al-Azzaz and igniting the ire of her brother Abdulrahman, a state security colonel, sending him on a power-tripping rampage. Disapproving of their relationship and unwilling to allow Rasha’s elite, merchant-class status to be possibly tarnished by a union with a lesser man. Abdulrahman then digs into Mohammed’s governmental files, discovers his stateless past, manipulates his files and relegates Mohammed back into statelessness.

“My homeland is my one eternal handicap I’ll never be cured of,” opens Kaliska. That yearning for homeland — even while inside it — pervades the entire novel, and Al-Dhafiri translates much of his own experiences onto his characters. Like Al-Dhafiri, Mohammad ultimately endures a forced migration to Canada where his yearning for Rasha and Kuwait alike morphs into contemplating the meanings of city and state.

“[W]e can’t see cities past our relationships with them, so to compare between your city and the next, even if it is more beautiful, is as if to compare between your lover and all the other women of earth,” writes Al-Dhafiri, in one of Mohammed’s more romantically driven moments. And of Mohammed’s more bitter moments, as he recollects Abdulrahman’s cunning imprisonment and physical torture, Al-Dhafiri writes: “the state believes it owns the nation and those who live in it. It grants its citizenship to this person and forbids it to that person. When you can separate the state from the nation, then you can ask me to differentiate between them.”

The impact of Al-Dhafiri’s body of work goes far beyond representations of statelessness. With a growing popularity for bidun literature among Kuwaiti readership at large — from the poetry of Mona Kareem and Dakhil Al-Khalifa to the novels of Jihad Mohammad and Abdullah Al-Husseini — wider audiences are offered a rarity: narratives that rend collective wounds open. The blood that gushes from these lived experiences seeps through the structures of class and nation building alike. In a critical sense, these accounts present a counter thesis as to why Kuwait City was built, why Silk City will be and why Jahra never was: to preserve the borders inside borders.

If countries’ borders are inherently violent, then how much damage can the invisible borders within do? This is a lonely city-state because it doesn’t permit people to cross even those lines drawn in the collective consciousness.

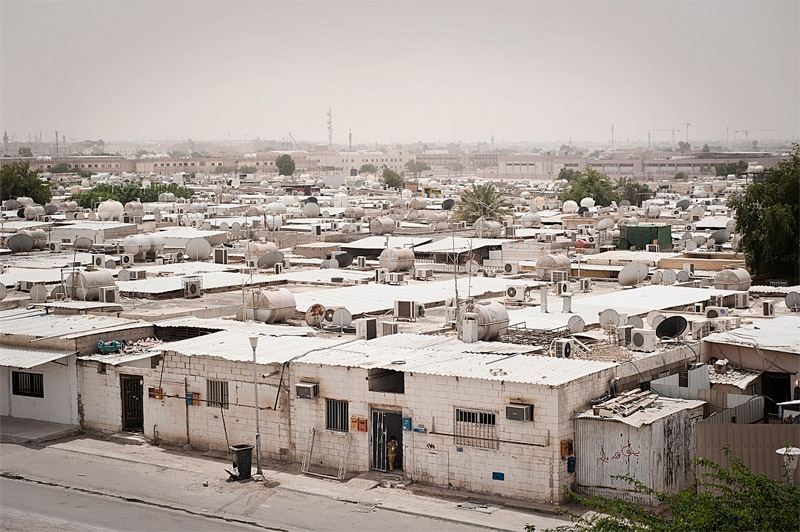

Driving past Doha and through Jahra itself, the roads loop around the once-celebrated trade post to a historic royal fort and green pastures rarely found in a scorching desert. Today, Jahra’s architecture strongly mirrors the classist dichotomies of Kuwaiti society. Opposite two private universities, one Canadian and one American, with a stretch of private villas housing mostly western faculty, sits another strip of stereotypical Kuwaiti houses. Designed with obsessive privacy, one home after the next makes for neighborhoods that look like a concession of giant concrete juice boxes. Across these lavish homes and overpriced institutions, sheets of industrial steel dot the bidun shanty town of Taima. Shaped into rectangular living quarters, the steel sheets house a people deprived of effectively all civil rights.

Just as the sight of Taima is impossible to unsee but easy to dismiss, the same rules apply to Kuwait City. While the capital boasts more shoddy buildings housing migrant laborers than it does luxurious skyscrapers and malls, the question that begs to be asked is: will Silk City house the same dynamics or will it be a home to all?

Once again, fiction might offer us a clearer glimpse of reality, as well as perhaps an idea to imagine our way to a different one. China Mieville’s The City and the City is a detective story in the oddest three-dimensional setting. Situated in the fictional Eastern European twin city-states of Besźel and Ul Qoma, citizens from both states are prohibited from acknowledging one other. While the two cities overlap in geography, both existing in the same space but with some homes or establishments designated as Besźel and others Ul Qoma, the cities maintain their separation only through the compliance of their respective citizens. Citizens of Besźel must never acknowledge those of Ul Qoma and vice versa; any form of interaction with the opposing state is punished by Breach, a secret policing body eponymous with the crime it punishes.

The only thing more useless than a bridge leading nowhere is a bridge that leads back to square one, to a future that simply keeps repeating all the mistakes of the past.

To avoid breaching, citizens must unsee, unhear and unsense everything and anything from the other end, all the time. If someone from Besźel walks out of their front door to see an Ul Qoman dying on the opposite street, calling for help might save a life but would constitute a crime on multiple levels. Alongside the twin city-states, Orciny is a conceptual third city brought to life in the minds of those who believe in it, creating a psycho-spiritual polity of sorts that all citizens can be in without breaching. There, the structures of citizenship are substituted with the structures of consciousness; no one in Orciny is breaching if everyone is simultaneously connecting.

Currently, Kuwait offers no third place for its denizens to connect. Driving across Jaber Bridge, only to arrive at a nowhere that was supposed to be Silk City is a breach to the shiny Vision 2035 version that the state wishes to have its citizens see. In late September 2023, Kuwait announced an updated version of Vision 2035, tacking on another five years and calling it Vision 2024-2040. If the past is anything by which to judge the future, we may never see Silk City at all.

In The City and the City, detective Tyador Borlu solves the novel’s central case and discovers Orciny, only to be coerced by Breach into becoming its agent. In Kaliska, Mohammed kills Abdulrahman in a snowy Canadian forest, only to have the authorities arrest him shortly thereafter. In those press releases I’ve written, corporate interests are aligned with state ambitions, only to convey national plans that center profits over people. On Jaber Bridge, the falcon’s upper and lower beaks are connected, only to lead towards empty land and another more violent nowhere beneath it — where the marginalized go to die. In all cases, there is a strict state bureaucracy that limits ambition and clearly reminds people of their positions and possibilities.

If Kuwait is to achieve an Orciny, some level of collective awareness of all the people we’re meant to unsee, those who embark on a way forward must consider their final destination. Are we heading toward a place for some or is it a place for all? Are we simply perpetuating cycles of violence, both visible and invisible? The only thing more useless than a bridge leading nowhere is a bridge that leads back to square one, to a future that simply keeps repeating all the mistakes of the past.