This summer’s major exhibition at the Mucem in Marseille is devoted to Emir Abd el Kader, the great Algerian resistance fighter against France’s colonial invasion. One might see this as a sign of progress in the recognition of the illegitimate nature of the colonial enterprise. This is not the case. Behind its formal beauty hides the same colonial vision of the “good” Algerian rebel, as opposed to the “bad fellaghas” of 1954. The exhibition is on view through August 22, 2022. For those who read French, the exhibition catalogue, published by Actes Sud, contains texts that are more critical than the exhibition itself.

Pierre Daum

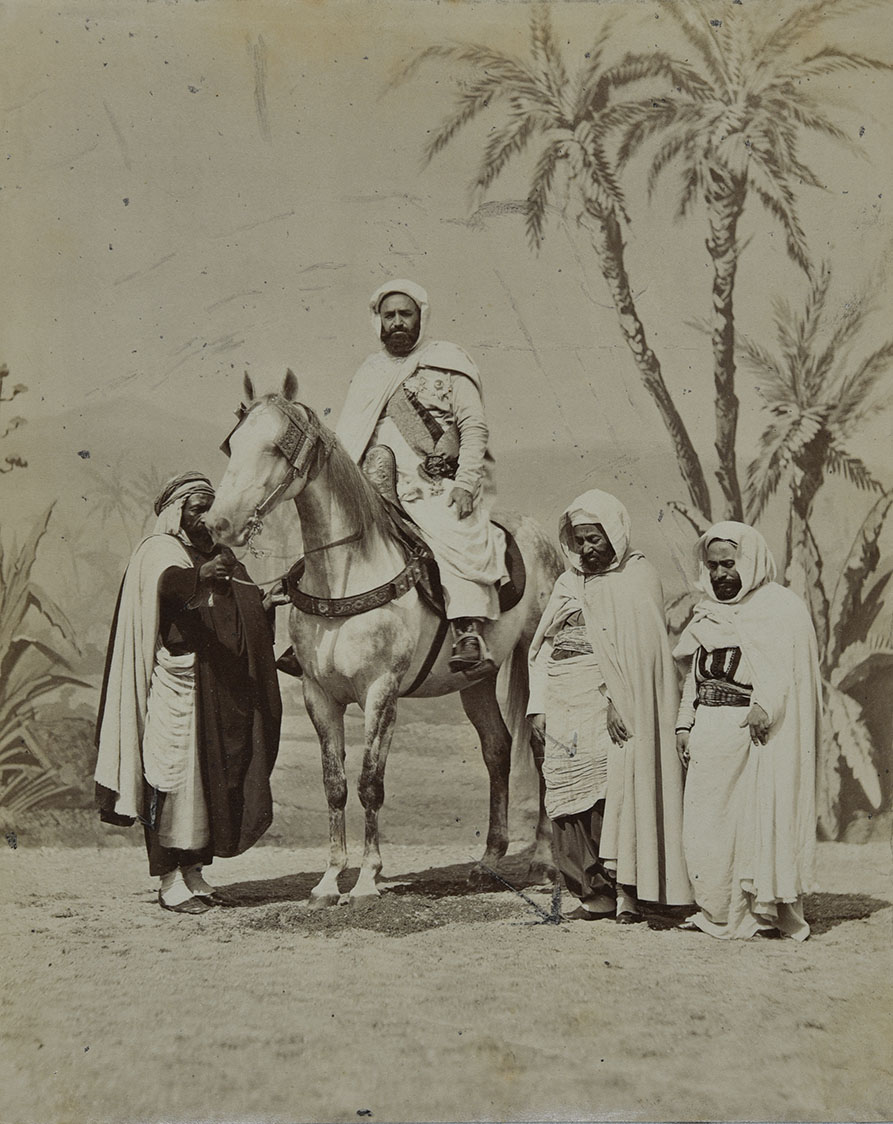

For its major summer exhibition, the Museum of Civilizations of Europe and the Mediterranean (Mucem) in Marseilles has chosen to present the life of Emir Abd el Kader (1808-1883), a great Algerian historical figure. This exhibition, which opened in April, has received unanimous praise from the press and various commentators.

Constructed according to an efficient chronological sequence, with paintings, swords and original manuscripts quite well displayed, the exhibition does not suffer from any formal imperfection. Similarly, we can only praise the intention of the Mucem to highlight an Algerian character as important but little known to the French, and considered by the Algerian authorities as one of the first heroes of resistance to French colonization.

However, on closer inspection, one is appalled to note that behind the magnificence of the presentation reappears, without any critical perspective, the same narrative of the “fierce fighter who ends up surrendering and loving France,” constructed by the colonizer as soon as Algeria was “pacified.”

A little historical reminder: Born in a family of the Algerian marabout aristocracy in the west of the country, near Mascara, Abd el Kader united several tribes under his command in 1832, and led a war of resistance for fifteen years against the French invaders. He finally surrendered his arms in 1847 in exchange for the promise of free exile to the East with his family.

A few weeks later, the French authorities perjured themselves and imprisoned him and his family (about a hundred people) first in Pau, then in the castle of Amboise. He remained there for four years, in very harsh conditions (cold, humidity, malnutrition), before being released in the fall of 1852 by President Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, two months before the latter proclaimed himself Emperor of the French.

Emir Abd el Kader then went into exile in Turkey, then in Syria, where he spent 28 years (from 1855 to 1883), before dying there, at the age of 74. In 1966, President Boumediene had his ashes repatriated for a burial with great pomp in the “martyrs’ square” of the El Alia cemetery in Algiers.

The exhibition at the Mucem does not in any way diminish the violence of the French army, even evoking the massacres of Algerian civilians who were supporters of Abd el Kader during the “enfumades” carried out according to the “Bugeaud doctrine” by generals Cavaignac and Pélissier in 1844 and 1845.

The French perjury is widely documented, as are the conditions of life in Amboise: an archive tells us that of the 94 people making up the court of the Emir, 25 died there, including one of his wives and two of his children. Then comes the release of the unfortunate prisoner, after a short visit of Louis Bonaparte to Amboise.

A large painting by François-Théophile-Etienne Gide, Les chefs arabes présentés au prince président (1852), appeared in the exhibition, showing Abd el Kader kneeling before the master of France and humbly kissing his hand. A text written by the curators of the exhibition explains that the Emir, rather than leaving immediately for the Middle East, decided to go to Paris to thank the French prince for his magnanimity. There is no other explanation — as if it were natural that this betrayed rebel leader, unduly imprisoned, who saw a quarter of his family and followers die of hunger and disease in the freezing rooms of the castle of Amboise, whose thousands of followers were “smoked” on the orders of the French generals, should decide to delay his installation outside the country of his prison to come and humbly kiss the hand of the head of the enemy state.

Was the Emir a victim of a Stockholm syndrome before its time? Or was there a secret negotiation between him and President Bonaparte in which, in exchange for his freedom (and an annual pension of 100,000 francs, we learn from a facsimile of the Journal illustré of 1852), he undertook to help the latter to build up an image of power and goodness useful for his institutional coup d’état organized two months later — and in the ceremonies of which, further delaying his departure, Abd el Kader was to participate?

The exhibition does not ask any questions, implicitly adopting the idea of the time that all Algerians, especially if they were wise and intelligent like the Emir, could not but recognize not only the military strength of France, but above all the power of its values of modernity and humanism.

From then on, it is in this vein that the exhibition continues.

We see Abd el Kader exchanging correspondence with several great French minds, in which he expresses his admiration for France, its people and its spirit of modernity. He made several trips to Paris to participate, as a distinguished guest, in the universal exhibitions.

An entire room is devoted to his unwavering support for the project to build the Suez Canal by the French diplomat and entrepreneur Ferdinand de Lesseps, an eminently colonial project designed to transport raw materials from Indochina and India to Europe at lower cost — yet the exhibition says nothing about this, preferring to report the Emir’s praise for a canal “linking the peoples of the East to those of the West.”

And above all, the Mucem shows us an Abd el Kader who is certainly Muslim, even very pious and very practicing, but Sufi — which means, in the Western imagination, a nice Muslim who is not at all aggressive. And moreover, he was vaguely a Freemason, a clear proof of his “tolerance”!

The exhibition concludes with the famous anti-Christian riots of July 1860 in Damascus, where Abd el Kader would have interposed himself at the risk of his life to save them. This episode is repeated ad nauseam as soon as it is about Emir Abd el Kader (the exhibition even makes him a “precursor of human rights”), as if it were a priori surprising that a Muslim would want to save Christians. On the other hand, there is no mention of the religion of the assailants, suggesting that they were Muslims, when in fact they were Druze, an ethnic group whose Ismaili beliefs are far removed from Islam.

Almost a century later, in 1949, four years after the uprising in Sétif and Guelma and the subsequent massacres of Algerians, the French governor general of Algeria erected a large stele near Mascara in memory of Abd el Kader. On the main face of the monument is inscribed a phrase attributed to the Emir:

“If Muslims and Christians would listen to me, I would put an end to their differences and they would become brothers inside and outside.”

This is a magnificent piece of propaganda, which empties all political meaning from the protest against the colonial order inaugurated in Sétif, and which, instead of denouncing the crimes perpetrated by France on the Algerian people over the last century, proposes “the appeasement of communities.” This stele does not appear anywhere in the Mucem. And yet, understandably, it would have been welcome there, so much does its quotation reflect the Macronian state of mind at the origin of the exhibition.

The Mucem is indeed a national museum, inaugurated by President François Hollande in 2013. The appointment of its director is made by the Council of Ministers, and the choice of its major exhibitions requires the approval of the Minister of Culture.

After inaugurating the erection of a stele in homage to Abd el Kader in Amboise on February 5, 2022, the Élysée cited the exhibition at the Mucem in a press release dated March 18 as part of the “truthful approach [of President Emmanuel Macron] aimed at building a common and appeased memory.” The next step will be the creation of a “museum of the history of France and Algeria,” which should open its doors in Montpellier, the statement said.

A scientific committee has already been set up, led by Florence Hudowicz, curator at the Fabre Museum in Montpellier, who happens to be co-curator of the Abd el Kader exhibition at the Mucem. In 2003, a first project for a “Museum of France in Algeria” was launched in Montpellier by Georges Frêche, the city’s sulphurous former mayor. In the words of the mayor, this museum was intended to “pay tribute to what the French did there.” After a first resignation of the scientific committee, shocked to be insulted by Mr. Frêche (“I don’t give a shit about the comments of asshole academics, we’ll whistle at them when we ask for them!”), the mayor had asked Florence Hudowicz to try to relaunch the project. Then he died, his successor took up the torch, and a new scientific committee was formed, still under the direction of Ms. Hudowicz.

In 2014 came a change of mayor and the project was abruptly abandoned. Today, it reappears at the heart of Emmanuel Macron’s memorial policy, supposedly in a radically different spirit, according to the few elements gathered here and there. If we look closely at the exhibition at the Mucem, we have every reason to doubt this.

* A smaller exhibition devoted to Abd el Kader, L’Emir Abd el-Kader, un homme, un destin, un message, is on view in Montpellier at L’Art Est Public, through July 31, 2022.

This column first appeared in French in Pierre Daum’s Mediapart blog, and is translated here by Jordan Elgrably.