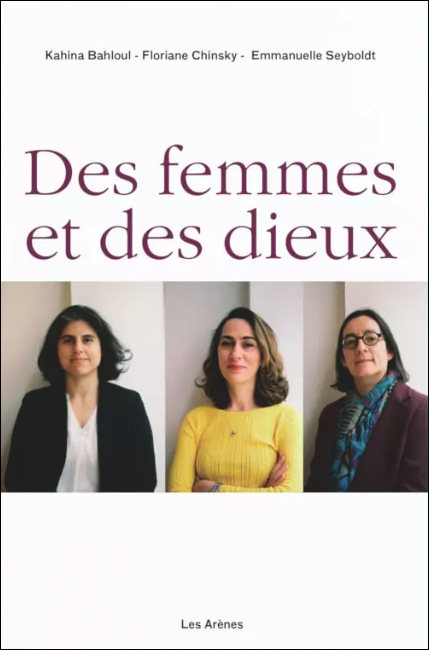

If the world past and present is torn by religious strife, some women find strength in unity and choose to work together to make their voices heard. This is the case of Kahina Bahloul, Emmanuelle Seyboldt and Floriane Chinsky, respectively imam, pastor and rabbi, who have written a book entitled Des femmes et des dieux (Women and Gods), published by Les Arènes (2021).

Laëtitia Soula

The Franco-Algerian Islamologist Kahina Bahloul was the first woman imam in France. Pastor Emmanuelle Seyboldt is the first woman president of the national council of the United Protestant Church of France, and Floriane Chinsky is an ordained rabbi at the Schechter Institute of Jewish Studies in Jerusalem. What brought the three of them together? Their decision to confront patriarchy by writing a book melding feminism, spirituality and religion, in which they talk about the personal obstacles they’ve faced, along with prescriptions for bettering society.

“Women must speak up”

Kahina Bahloul affirms that women “can and must speak out. We may say that we are in a democratic country, that women have acquired a certain social status, but I observe that they often remain on the margins, especially in the business world. They have occupied this marginal position to such an extent that they no longer dare to return to the center of the action. It is anchored in our feminine behaviors, in an unconscious way, in each gesture of daily life. Even though we live in France, in Europe, there is always the risk of going backwards, unfortunately. The message we want to send is that we must be very vigilant,” Bahloul adds during an interview with TMR.

“An important point is to involve men in this vigilance, in the face of possible setbacks in women’s rights. Favorable frameworks can exist and allow us to move forward,” explains Floriane Chinsky. “As an example, I can attest that at the rabbinical seminary I attended in Jerusalem, there were male students who were more feminist than some of the female students. Some of the study partners needed men to lead the way in feminist equality. It is an honor! In the book, we ask the question of whether women’s place undermines the honor of the community, because that is an argument that may have played out. I would say that it is up to women and men to consider women’s place as normative, that it is an honor that we can be equal with each other. One of the things I learned [in the process of writing this book] is that the United Protestant Church of France operates with 50% women.”

“A new wind of life”

For Emmanuelle Seyboldt, the objective of the book is to “demonstrate that being a believer is not an obstacle but an encouragement to the commitment and participation of women in life.” The book is an opportunity to tell the story of their paths and what emerged from their encounter. The origin of their vocations, the questioning of the patriarchy that impregnates religions and traditions, what the texts say about the feminist question or the place of the body are all subjects they address.

It is reassuring to see that progressive women and religious leaders are addressing the major issues of society with an open mind and in a spirit of dialogue. In this way, ideas are exchanged, convictions are articulated and each one discovers the codes of the others and gives them the space to express themselves.

For Bahloul, the challenge is to breathe into the process “a new wind of life, because we often tend to look at religions as dusty, outdated phenomena. The idea is to revive them and to embody in the 21st century a way of enlightening these religions, of interpreting the texts, with a feminine method of course. What makes the difference between medieval thought and today’s thought is that we women have all the tools to speak out, to make a place for ourselves within religions and to bring them to life.”

According to the Islamologist, “To ask whether religious texts are feminist or misogynist is a question of intellectual dishonesty. First, it is completely anachronistic. The Quranic text is a reflection of Muslim society in the Arabian Peninsula in the 7th century. To understand it, it must be put into context, hence the importance of historical-critical reading.”

The authors therefore propose to reject the thesis of a pre-established feminine essence and to recall that each person is defined by his or her life choices, questioning the precepts of certain religious traditions and rejecting the superiority-inferiority relationship, in favor of complementarity.

The same pay for the same work

When asked about the main demands made by women, Seyboldt admits that she is shocked by the salary inequality: “I choke every time. How is it possible that men and women don’t get the same salary for the same work? I don’t understand why we still have to talk about it,” she says.

It is an inequality that could be brought back to the one of the body, a theme the authors confront in Women and Gods. And it is quite surprising to see that the authors bring back this body to a promise and not a condemnation, reminding us that it is precisely the woman’s body that tends to pose a problem. How many discussions, controversies and polemics have been sparked by a body that no longer belongs to the woman, but to the patriarchy itself?

Bahloul believes that it is necessary to work for an equal and fair sharing of the public space: “We may live in Europe, but today we still see resistance, we see the resurgence of anti-feminist behaviors that exclude women. Working for an equal and fair sharing of the public space is, in my opinion, a strong claim that we must make.”

Chinsky argues that the ideal would be to move “towards a society in which there would be no need to defend women. In the fight against domestic violence, for example, we can call a number and find emergency accommodation. That way, a woman who has to leave her home with her children will know that she will not be sleeping on the street. We must promote access to rights for each disadvantaged social category, as far as universal resources are concerned, because everyone has the right to be warm, to be able to eat, to be housed, to be educated. This is an essential basis.”

Kahina Bahloul

Kahina Bahloul

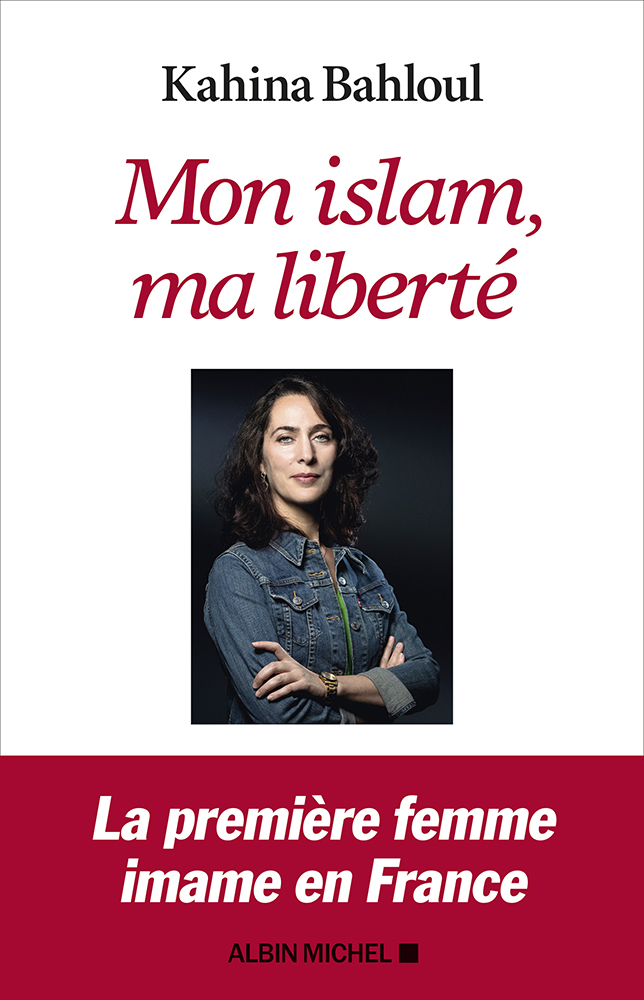

Kahina Bahloul is a Franco-Algerian Islamologist and a Sufi. She was the first woman to declare herself an imam in France, in 2019. Bahloul is the co-founder of the religious association project The Fatima Mosque, which promotes a liberal Islam.

Bahloul was born in Paris on 1979 to an Algerian Kabyl father who was not very attached to religious norms, and a French atheist mother. Her maternal grandmother was a Polish Ashkenazi Jew, her maternal grandfather a French Catholic. From the age of one she was raised in Algeria, near Béjaïa and the sea, and remained in Algeria until receiving her law degree. She returned to France in 2003 and “distanced herself from the [Muslim] religion” for a few years. She became an insurance executive for 12 years, but the death of her father led Bahloul to deepen her link with Muslim mysticism and Sufism, in which she claims to have found the answers to the questions she has been asking herself since childhood.

The November 2015 Bataclan and other attacks in France were her call to action. She returned to the university and after obtaining a master’s in Islamic studies at the École Pratique des Hautes Études in Paris, Bahloul pursued a doctorate on the thought of Iban Arabi, the Sufi theologican and 7th century poet. Bahloul launched the channel and the association “Parle-moi d’islam” (Talk to Me About Islam). In addition to Ibn Arabi, a major source of inspiration for Bahloul is the Sufi Rabia al Adawiyya, whose biography is mostly legendary and invented. As a Frenchwoman of Algerian origin, Bahloul also relies on the Sufi Abdelkader ibn Muhieddine.

According to Bahloul, the meditative practice of Sufism abolishes gender considerations. She is inspired by the Danish imam Sherin Khankan and the American figurehead of Muslim feminism, Amina Wadud. Bahloul says, “It is a fact, since the 12th century, and the writings of Ibn Arabi, that nothing prohibits a woman from leading prayer.”

“Opinions that seek to establish the absolute prohibition of female magisterium in Muslim worship have no sound theological basis,” she argues. “No argument from the Qur’an or the Sunnah can be seriously advanced to invalidate or make unlawful the imamate of women.”

While Kahina Bahloul declared herself an imam in the Spring of 2019, no official representative of Islam in France has yet taken an official position on her status. Also, for security reasons, her congregation has no fixed location.

The question of the legitimacy of Kahina Bahloul is often raised. Critics have pointed to her inexperience. “If they think that this will make me change my mind, they are mistaken,” she says, “It is perhaps related to my first name, which refers to an inflexible Berber queen, but I do not give in to pressure.”

Last year, Bahloul published My Islam, My Freedom, in which she elaborated on her thinking.