For this young Moroccan novelist, the memory of his mother, M’Barka Allali Taïa (1930-2010) is indelible. In the present excerpt from his most recent novel published in French, Vivre à ta lumière (Living in Your Light), Taïa devotes his story to Malika, the heroine she inspired. The novel will be translated by Emma Ramadan for Seven Stories Press and is due out in 2023.

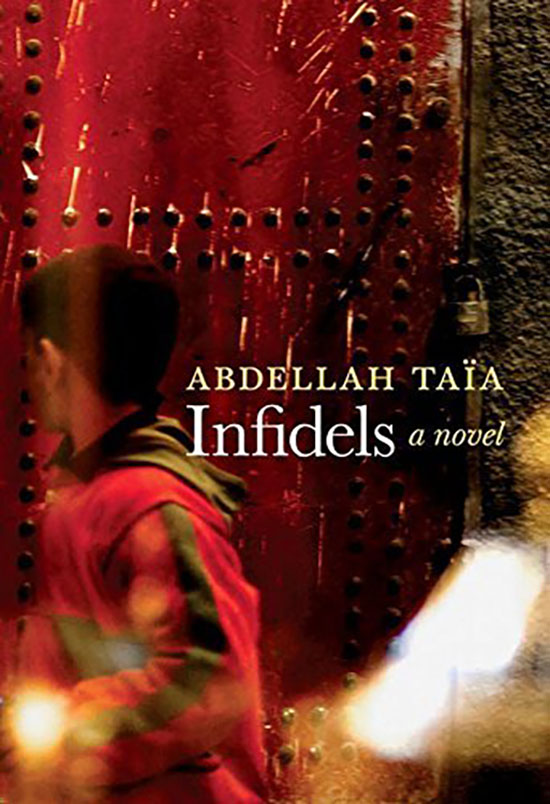

Abdellah Taïa

My children were right. This woman is white, so white. It’s incomprehensible, how can she be so white? It’s not skin she has, no, it’s milk. I have water in my mouth. I want to lick her despite myself. To go up to her and, without saying anything to her, to lick her skin. Taste her skin very slowly. To drink her milk. It’s impossible, this skin, especially here in Rabat, especially now, in the middle of August. I’m swimming, it’s dripping all over my body. Rivers and rivers of sweat. I can’t take it anymore. I think I’m going to faint. But she, who is not even from this country, does not sweat worse. She really doesn’t sweat. I look at her and I look at her. And I can’t believe it. She walked the same way as me to this monument, the ruins of Chellah, and not a drop of sweat is visible on her.

What’s her secret? It’s frankly unfair. To be so white, so beautiful without make-up, and to be able to stand the blazing Moroccan heat without any problem. I was born here and have always lived here, but I have no solution. The sun does not like me. It hits me, cuts my head in two by dint of migraines day and night, throws me into an ocean of hot and cold perspiration at the same time. Only the eucalyptus leaves help revive me, a little. I crush them in the mortar and put them on my forehead. A little freshness. A bit of cold that goes through my head. A little spring in the middle of summer. But I made a mistake: I forgot to cut some branches from the eucalyptus trees that were on the road. Where I am now, at the entrance of the Chellah ruins, there are no trees.

There is only her. White. Fresh. Well dressed. Only her and her milky skin.

She smiles. Why is she smiling? I must not respond to her smile. I have to stay strong, the strongest. I am not a nice Malika. I am not the Arab woman she thinks I am. I’m not going to smile.

My name is Monique. She says.

She keeps smiling. That’s her strategy in life. Always smile. Well, with me, it won’t work. I won’t smile at her. I’m not nice, I’m mean. I’m intractable. I can’t be bought, me, Malika. At least not with little smiles that come from another world.

No.

My name is Monique. She repeats it.

I know her name is Monique. Why does she insist?

Ana smiti Monique.

She says it in Arabic now. She is really has no shame. She speaks in Arabic. She has no right. It doesn’t impress me. It doesn’t impress me at all. Why does she speak Arabic like us? To get closer to us? To know us better? I doubt it. I doubt it.

She opens her mouth and lets the words out in Moroccan Arabic.

Ana smiti Monique.

Monique. Monique. It’s all right. It’s all right. I know what your name is.

“Monique” sounds like “monika.” A doll.

This Monique is not a doll. I’ve known that too, for at least two months. She’s the opposite. She’s smart. She goes for it and attacks. She never asks for permission.

She still looks ridiculous when she speaks Moroccan.

I feel that she will tell me now that my name is Malika. She knows my name. In advance.

That’s what she does. She is not ashamed. She looks me straight in the eyes, she smiles, she acts innocent, naive, and she says Moroccan words. She says my name for the first time. Malika. Then twice in a row. Malika. Malika. I wonder why.

It grates on me.

I look her straight in the eyes too and I still don’t smile. I didn’t come all this way, I didn’t endure the heat of this road to Chellah to play nice with this Monique. I will never be your friend. I came for something else. She knows that and she acts as if that is not the most important thing right now. She wants to impose the rules of the game. To be the French boss? Bossy but nice. Bossy and gentle. Boss to the ends of her fingernails, but look how I don’t sweat in the middle of summer, look how fresh I am, how good I smell of vetiver, how elegant I am, how beautiful I am, how white I am, and how much more I know.

I’m not impressed. It’s not like me to be dominated so quickly. No. No. He is dead and already buried, the one to whom I had given the keys to my heart. He’s dead. Dead. Allal. I don’t have a boss anymore.

How to make this Monique understand? How can I make her look at me differently?

Read a review of Abdellah Taïa’s Vivre à ta lumière/Living in Your Light

Let her stop smiling. Let her stop speaking in Moroccan. It doesn’t suit her. Let her stop acting like she’s being kind to us. Let her stop. We don’t need her pity, let alone her understanding. Let her lower her gaze and even her head. Then I can look at her with my eyes, finally. Let her drop the mask of the modern Frenchwoman who is so touched by the simplicity of Moroccan life. The colonization ended almost ten years ago. Why does she persist in staying here? What the hell is she doing here in Rabat? I know from my husband Mohammed that she was born in Casablanca in the thirties and lived there until she was ten years old. And, of course, she could never forget Morocco, the beauty of Morocco, the sky of Morocco, the light of Morocco. And the poverty of the Moroccans, does she remember that? Of course she remembers it, and that’s why she comes back here with her husband and their children. She wants to show them how great this poor country is. It’s great.

That’s right: Morocco is great. For-mi-da-ble.

Since our arrival in Rabat, thanks to the job my husband managed to find at the central library, not a week goes by without someone bringing me a touching story about the great beauty of Morocco.

Since I’ve been in Rabat, I am shocked every day. I thought the French left Morocco in 1956. But they didn’t. Not at all. They are still here, here and there. They live in the villas in the beautiful neighborhoods of Rabat. Hassan. Agdal. Les Orangers. They are at home. And even when they leave, they end up coming back. You can’t forget Morocco. You can’t live without Morocco. Nostalgia for Morocco, they say.

I don’t want to get into the logic of this nostalgia.

Monique lives in a beautiful villa in Les Orangers district. Herself, her husband, their two boys. She has everything. What more does she want?

She doesn’t have a daughter. Ah! That’s what she’s missing. A little girl.

Poor Monique. How I pity her… But she found a solution.

Monique wants to steal my daughter. My own daughter. Khadija. Who is barely fifteen years old. Khadija, the most beautiful of my daughters, this Monique wants to take her in as a maid. A little maid.

Khadija will be like my daughter, she dared to say to my husband Mohammed.

And he, idiot, happy fool, he agrees. Give her Khadija. She will have a future with Monique. That’s what you have to do. It’s good for Khadija. Whether you agree or not, Malika, you have to think about what’s good for Khadija. This is a great opportunity for her. To get in with the French. Can you imagine? Working for the French. It’s the royal road. They’re rich, Malika. Rich. I know they are.

From one day to the next, this name, Monique, was all over my house, on everyone’s lips, in everyone’s dreams. My six daughters spoke only of her. Monique is beautiful. Monique is coquette. Monique is bourgeoise but kind. Monique has such white skin. She is incredible!

The whiteness of her skin had completely fascinated my daughters. They were conquered. Monique was the dream.

My daughters are already fighting among themselves to take Khadija’s place, in case for some reason she changes her mind.

Translated from the French by Jordan Elgrably