The co-editor in chief of Diacritik reviews the latest novel in French from Moroccan writer Abdellah Taïa, devoted to the heroic figure of his mother.

Jean-Philippe Cazier

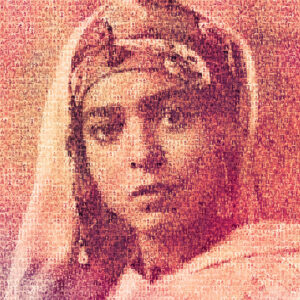

Malika is the central figure in Abdellah Taïa’s novel, Vivre à ta lumière/Living in Your Light. She is the character of a mother, a Moroccan woman. At the same time as you have these individual identities, her figure condenses a network of wider dimensions and relationships: colonization, balances of power, the strata of Moroccan society yesterday and today, and those of a plural, obsessive, complex, even split psyche.

The novel develops these multiple dimensions, intertwining them less to analyze them abstractly than to highlight their effects, their individual and collective power. Two of the recurring themes of Taïa’s work are reworked and redistributed: identity and power. The construction of the novel is musical: three parts that weave, arrange, and rearrange the themes, the relationships between the characters, between the political, social, and psychic dimensions, intersecting with or superimposing over or joining subjective History and history.

The three parts correspond to three different moments in the life of Malika (a name whose etymology refers to the idea of “Queen,” of power: object of admiration, powerful subject, subject of power…). As a young girl at the beginning of the novel, Malika undergoes what in retrospect may appear to be the destiny of her entire life: to fight, to survive, to be a strong woman. But her individual destiny is inseparable from a common, collective destiny, linked to colonization, to the form of power in Morocco, to the gendered order of Moroccan society, to the social order of economic relations. As a mother, as a woman who has to fight daily for her autonomy, to escape from what the general order of the world imposes on her, she is indeed, in her own way, an admirable and powerful “queen,” all the more “queenly” because she is among the most miserable, because she belongs to the people of the poorest, the most neglected and invisible, forgotten.

Malika’s struggle is a struggle for survival, for honor, for autonomy within an economy of misery, an economy that is the effect of capitalism as well as colonialism and the confiscation of wealth by those in power. It is also the effect of the place given to poor women in Moroccan society (but not only). It is an individual, solitary struggle, a struggle of a poor person who thinks of herself as a separate individual, but who nevertheless possesses an awareness of the broader causes of her situation and of the necessity, for her, of the struggle. Taïa’s choice is both aesthetic and political: to bring into the field of literature a woman who is usually excluded, this poor, uneducated, lonely woman — to bring her into existence and to “glorify” her not from a miserabilistic point of view but as a resister.

Her solitude is part of her glory, but it is also the sign of a kind of “confinement” in her subjectivity. If the novel does not put her into play as the representative of a collective movement of emancipation — a typical figure of political resistance — it is because it is a question of insisting on the individual, tiny, banal effects of power, seen here, in a way, at the ground level. It also underscores how power, in its global, collective effects, its general structures, is first confronted individually inside a conscience which has first to deal with itself, right away. There can be a consciousness of the world, there can be a globalizing point of view on the world, there can be a consciousness of the general causes and effects of the political, nonetheless each one has first to deal with herself, with her body, with her thought, with her emotions, with her absolutely individual existence. Any consciousness of the world would be first of all the consciousness of a point of view limited to oneself, to the immediate, to the singularity of oneself, even if this self encounters general lines of force, global events, common dimensions, the two being indissociable and confusedly mixed: at the same time in the world and outside, with the world and next to it, with and separated — the motive of proximity and separation being one of the red threads of this novel.

If there is always a sociological and political dimension in Taïa’s books, it is inseparable from a subjective dimension insofar as the most individual subjectivities are nevertheless informed by the social and the political, but also because there is a kind of tension between these dimensions that does not oppose them but implies that they cannot — and, in a sense, should not — entirely coincide, that they should be synthetically attuned. It is this tension that is also at work in Living in Your Light. It is these complex relationships that are entangled in the figure of Malika and that resonate with all the variations that run through and build the novel.

Read an Excerpt from Abdellah Taïa’s Vivre à ta lumière

Malika marries young. She chooses to marry but her husband is killed during the French war in Vietnam — a war that is not his war but in which he engages, on the French side, for the money, to try to escape the poverty that is his birthright and that he shares with his wife, that he can only pass on to his future children. Here we already have an individual effort to contradict social and economic destiny, an effort that fails because of death. Like the proletarian who has to survive, Allal has only his body and his life, which he exchanges for money — body killed, life lost, and with it the only way out of misery. Widowed, Malika is rejected, isolated, finding herself in the situation of dying not only socially but physically.

From the first moments of the book, the individual and the collective, the subjective and the social, the tiny history and the History of the world are woven together. And early on appears the figure of a destitute individual, possessing nothing but herself to try to draw another line in the general design of her destiny. The most general logic that structures the novel also appears: proximity is inseparable from separation. Allal is married to Malika but he also has a lover, Merzougue, he loves Malika but he also loves Merzougue. The marriage, the link, is broken by death, but it was also crossed by the love of Allal and Merzougue, a love to which Malika consents even if it implies a form of impassable distance for her between her and her husband. When Allal dies, both Malika and Merzougue mourn the deceased equally and both join forces to honor him. The allies are thus at the same time separated; the broken alliance gives rise to another alliance that will in turn be broken.

This theme of alliance and rupture, of the relationship itself crossed by separation, is repeated in different ways and at different levels throughout the book. The relationship/separation that concerns Malika and her family or her in-laws, but that also concerns, in a different way, the relationship between Malika and her second husband, between Malika and the French woman Monique, between Malika and Jaâfar, the young homosexual delinquent, between Malika and her son, of whom Jaâfar could be a double, at the same time him and different from him (the double, as another form of a proximity that cannot be dissociated from the distance). In the same way, Malika identifies with Morocco but rejects it, criticizes it, in a sense condemns it: she is always close and far, with and against, with and elsewhere, as close as possible and as far away as possible, just as the others or the world are always with her and separated from her, separated from her and with her, successively and at the same time. At the same time, in the same chiasmatic movement, the enclosure in oneself and something else than oneself, the link and the absence of link, the proximity and the separation.

This logic is recurrent in Taïa’s works where the relationship to the world is carried out according to a double movement: porosity and closure, presence and absence, opening and enclosure in oneself. The world is what determines me, including subjectively, as it is what I perceive and live only from a self restricted to its own representations that can involve compassion, love, desire, as well as anger, rejection or hallucination. Formally, Living in Your Light is made up of monologues, the dialogues being themselves, first of all, juxtaposed monologues: to address the other, to speak with the other, can only exist through an effort, more or less successful, more or less unsuccessful, never totally completed, to leave oneself. They are like distinct, distant worlds, which cross each other, brush up against each other, send each other more or less clear signals, more or less perceived, more or less understood, each one expressing what it is itself in a kind of song or solitary cry, even if it is a song of love, of desire, or of hate. The relationship with the other is always made in the background of a wrenching away from oneself, an effort or a fight that is never totally finished.

This constant entanglement and tension between proximity and separation informs the logic of identity at work in Living in Your Light, as it does in Taïa’s other novels. Here, identity is not natural or given, it is constructed by identification and is undone by misidentification. Nothing is always what it is, each identity is also different from oneself, each identification is crossed by a difference, each one is oneself and something else than oneself because what is exists only according to plural, multiple dimensions which clash, coexist, join, exclude each other.

Thus, Malika is this woman who resists power but who is at the same time one of its relays, exercising it. In Taïa’s works, the idea of power is close to the one that Foucault elaborated: a power less defined by a property, a status, a function, than as an anonymous network of relations. Malika, for example, wants to extricate herself from the place she is supposed to occupy within this network of relations: striving to get out of extreme poverty, of the patriarchal order, also confronting the colonial order, she engages in a very individual way — but which already implies, however, a collective stratum — in a History that wants to be a counter-History. But she is at the same time the one who wants to decide for others (even if it means using witchcraft as a political power), the one who only listens to herself, deaf to the will of others, denying the possibility and the relevance of other points of view than her own, the one who lets her son undergo the rapes that Moroccan men impose on him, the one who is obsessed by the fact that her daughter marries a powerful and rich man, etc. Of course, this exercise of power is for her the condition of her survival, the means by which an anti-destiny is for her (and for her family) possible. But it is also the means by which she reproduces a power that she seeks to flee — in turn making this son flee, who seeks by means other than her (studies, literature, geographical distance) to escape the order of power of Moroccan society as his mother had done before him but in which, however, his mother participates against him.

The relationships between the characters are one of the elements that, in this novel, reveal the internal plurality of each identity, each one being able to embody another point of view on the others that highlights what the identity of the others masked, other sometimes contradictory dimensions of what had been perceived in a too simple way. This is the case, for example, of the relationship between Malika and Monique, or the relationship between Malika and Jaâfar. The same is true of Moroccan society, which is patriarchal and rigid, but where, under certain conditions, there is a habit of homosexuality, as expressed in the relationship between Allal and Merzougue, the son’s point of view, or that of Jaâfar. If Taïa punctuates his novel with the appearance of new revealing points of view, he also organizes the relationships between the characters so that they themselves produce variations that are just as revealing, or give rise to the emergence of new identities. The characters, their identities, are constantly mobile, as if each one were always capable of exhibiting new facets that had remained in the shadows, as if each one were a kind of kaleidoscope, a set of more or less disjointed fragments constantly in motion.

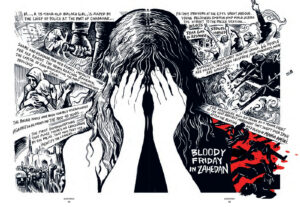

Living in your light is a complex novel, constantly articulating plural dimensions, dense relationships in a composition that would be music, comparable to what would be a mosaic created on the waves of the sea. It is also a political novel, not only because of the omnipresence of the theme of power, or its sociological dimension, or its point of view on colonialism and post-colonialism, but as it is also a critique of Moroccan politics and its identifying figure: the king, the corruption of royal power, the prison ideal of society to which he subjects each and every one, and to whom other figures are here opposed, such as that of Medhi Ben Barka, or that of Malika, the “queen” of a revolution already underway, already ancient, already existing — already, perhaps, happening? One of the questions that this book poses may be: what legacy to leave to one’s children, what legacy to leave to the youngest if not the imperative of resistance to the existing order?

Translated from the French by Jordan Elgrably, and originally published in Diacritik.