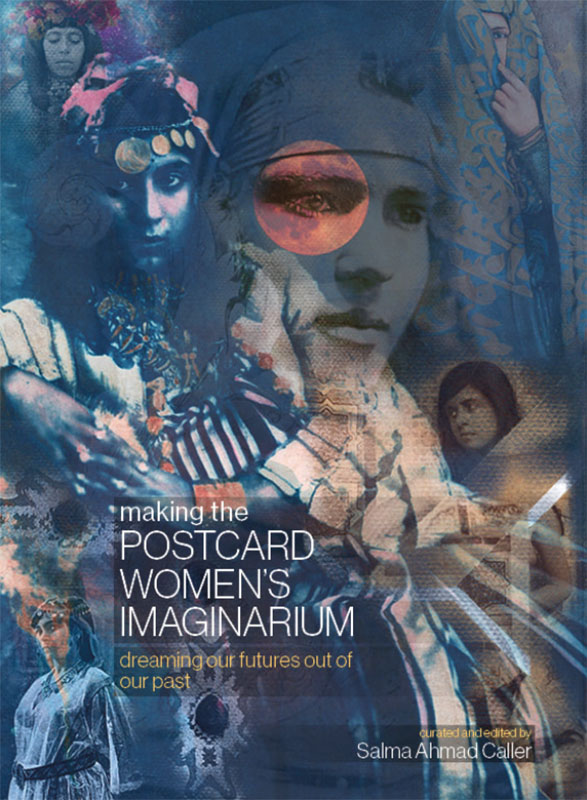

Making The Postcard Women’s Imaginarium is a project first created in 2018 by Egyptian British artist, art historian and writer Salma Ahmad Caller. The vision was to decolonize the representations of women from the Middle East and North Africa on colonial postcards, from the late 19th century to the mid 20th century. The Imaginarium postcard project was created for artists, academics, writers, and researchers to personally engage with the Postcard Women and their potential ways of being, to meditate upon different histories and geographies, and to become intercessors on behalf of the Postcard Women, rewriting histories and incorporating new perspectives and visions, reclaiming cultural riches and richness. Visit the Facebook group.

Salma Ahmad Caller

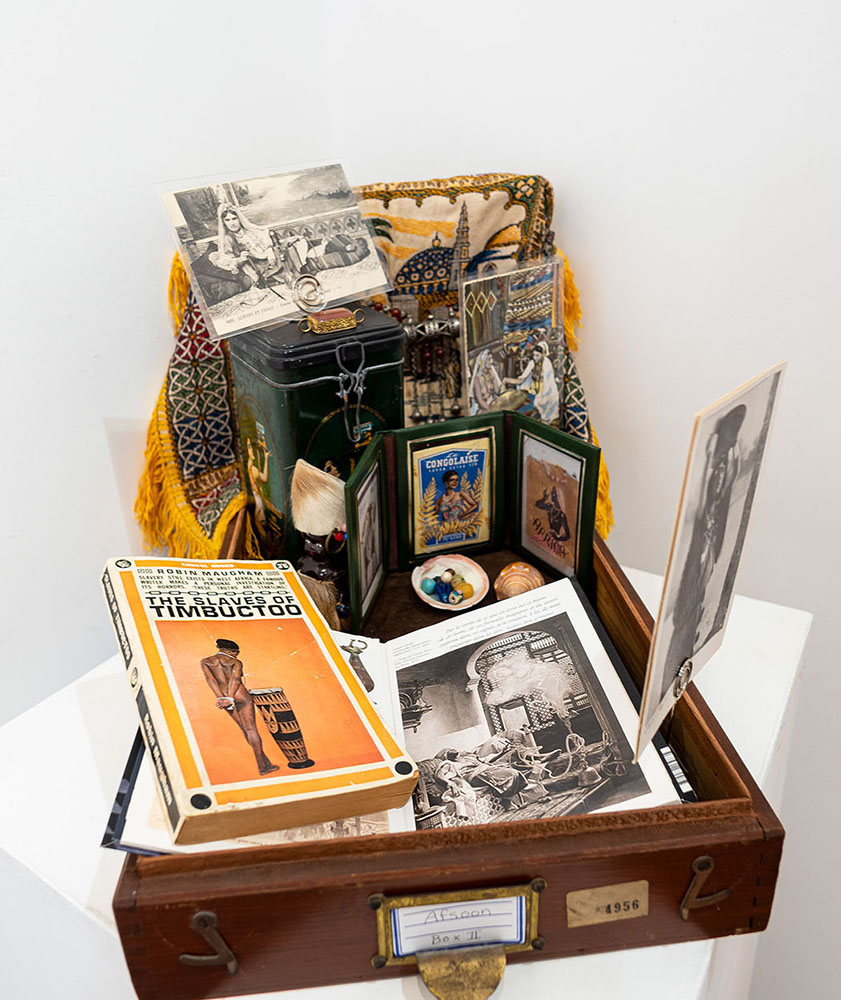

Wonderment and surprise was what we all felt when, after weeks of filling out funding applications, I received news that Arts Council England would provide the funding to run Imaginarium Phase II. I told my group and everyone was thrilled. We had been discussing this work since before the pandemic hit. Afsoon, an Iranian British artist, joined me at the start, when I founded the project in 2018. She had already been collecting Postcard Women of North Africa from flea markets in France. Afsoon is connected to Britain, Iran and France but also to Egypt and India. She is a creative collector and her assemblage boxes for our Phase II exhibition at Camden Image Gallery, which we recently dismantled, are remarkable. No one knows how to curate “things” like Afsoon, bringing them into a conversation across the so-called “East” and “West.”

What kinds of things? A memorabilia of colonial and Orientalist imagery, packaging and books, intermingled with jewels and faces of Postcard Women looking out from the strange world in which they found themselves.

Phase I took place in London in 2019 on a much smaller scale. Afsoon and I, along with writer Stephanie Nic Cárthaigh and Turkish poet Betül Dünder (translated superbly by Neil P. Doherty) were the key participants.

I had never curated before. My husband Christian designed the texts and visual materials and designed the sound. We had voices echoing throughout Willesden gallery in a modern space inside a library in Brent, in the midst of a multicultural area of London. Why the Irish presence, embodied by Stephanie and Neil? We met on Facebook, through discussions on decolonizing art and literature. The Irish community has a deep understanding of colonialism, having put up with and resisted it for 800 years. Neil lives in Istanbul and translates Turkish poetry, which should have a global audience but doesn’t because everyone is still so hung up on the European canon of “greats.” Betül wrote two haunting poems for that first exhibition, which you can now read in our publication Making The Postcard Women’s Imaginarium: dreaming our futures out of our past, (Peculiarity Press).

Stephanie has the most beautiful voice, full of tones and textures, with an Irish lilt, so we recorded her reading those two poems, “Beyrut” and “Some Women Leave No Shade ~ for all the slaughtered women,” in English, and Betül read them in Turkish. Christian suggested we play them on two different speakers, so that the two languages and voices intermingle. A cross-cultural soundscape.

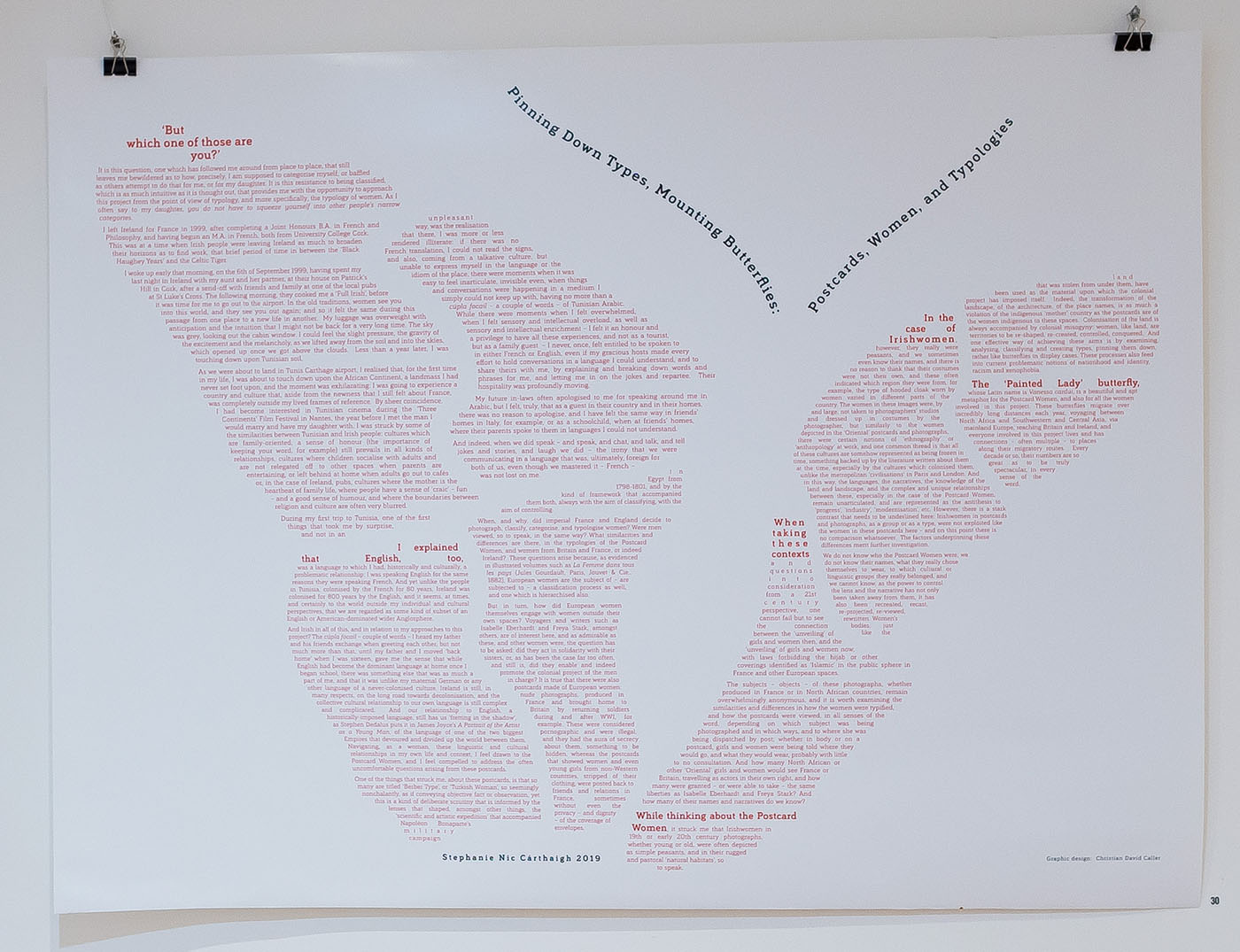

Stephanie lives in Paris; her daughter Salma has a Tunisian father. Stephanie’s essay in the catalogue, “Pinning Down Types, Mounting Butterflies: Postcards, Women, and Typologies,” is both critical and personal, drawing upon her own mixed heritage, her many cross-cultural experiences, and her bringing up a “mixed-race” daughter who is Tunisian, Irish/German and culturally French, too.

It is almost always assumed that the future will be better than the past. Our colonial oppressors taught us to be afraid of being labeled “backward” or “primitive.”

Our Imaginarium project is a chorus of many voices and backgrounds, from past and present, and is, in my opinion, a crucial bringing together of many cross-cultural strands and forms of critical thinking through art and writing, reaching beneath the superficial surface of the postcards to draw out many rich seams of meaning and interpretation. My voice was there too, in that first exhibition, and again in this one, reading from a range of texts, from Mona Eltahawy to excerpts from The Almond: The Sexual Awakening of a Muslim Woman, by Nedjma. You can now listen and watch the projections of images I created, online, in my film, Incantations of Veneration, Degradation and Protection: For the Untamed Displaced Mis-placed Woman.

I wanted to create a disturbing juxtaposition of sacred, profane, religious, philosophical and historical texts, and bring into relief how women are thought and written about, from the past and present. I wanted people to hear radical women’s voices speaking, through my voice. I projected refracted light and inserted multiple histories over my Egyptian Postcard Women, to activate the concealed colonial space and draw in layers of presences of others. “Palimpsests: Presences of Others” is both book chapter and installation, of photographs I had taken of these projections, and the things and materials I used to insert multi-ethnic Egypt into the frame. I also inserted my own subjective mixed Egyptian English presence, using things belonging to my English mother.

So, you can see how this all began. I started it because I was searching for my Egyptian self. I conceived of Making The Postcard Women’s Imaginarium project to be a space where opposites collide and voices intermingle, to make a tapestry to defy assumptions about Postcard Women and MENA women, but also to defy categorizations and disrupt the stereotypes, borders and boundaries that are woven around us, constricting our breath.

Imagination is everything. In this collaborative project of collective acts of healing, through talking, collecting, making, sharing, and research, I wanted to bring in as many voices as possible of women, and some men, dreaming and hoping to build a better future, one that was based on understanding the past, not hiding from it. Understanding the trauma that visual representations can enact matters. It is almost always assumed that the future will be better than the past. Our colonial oppressors taught us to be afraid of being labeled “backward” or “primitive.” And nothing has been so mummified by Western forms of representation and knowledge formations than our bodies, our jewelry and clothes, stripped away so that we should become “modern” and “educated,” and abandon our bodily archives of knowledge, created across generations, as if they were nothing. So we focused on bodies, jewelry and “props,” which characterize these images of women. Western racial and knowledge hierarchies, embedded deeply within knowledge systems, have re-created us, our female “exotic” bodies, as “spectacular” grotesquery in the margins. Setting us into history as silent ornaments, fondled, handled, categorized and stowed away. Our inner and outer lives erased.

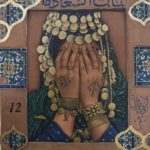

When we dismantled the exhibition this month, it felt like a destructive act, yet I knew a chain reaction had begun at last. Alia Derouiche Cherif’s mesmerizing re-imaginings of Ouled Nail women, mixed-media works, richly steeped in her Tunisian culture of “now” and “then,” seemed to still hang in the air, their iconic richness, blues, greens and golds, a lingering musk. Those hands covering the face of a Ouled Nail woman — a work Alia named “Beb el Saada: Door of Joy,” covering an image of the shame we are supposed to feel as women, or that historically Ouled Nail women have been made to feel, has now been transformed by her own hands into a potent gesture of refusal and sorrow.

Hamida Zourgui’s Algerian Madonna, “Algerienne 1,” a “typical” “belle Fatma” of Algeria now holding the body of Christ, has been packed away along with her ritual objects and their gestures, cast by Zourgui’s hands into ceramic. You must listen to Hamida’s call, beckoning us to go where the real Algerian woman lives, in so many key political, cultural and artistic arenas, still wearing her heritage and riches, and carrying her rituals and meanings inside her body. Hamida left France, tired of racism, and now lives in the U.K. A lady, who wishes to remain anonymous, who was working at the gallery at the time our exhibition was launched, was a surprise for me, when I walked in on the first day we opened at Camden Image gallery. She is a mixed Algerian French woman, brought up as a Christian by her French mother, and had only recently found her father’s family in Algeria, after many years of searching. She also harbors traumatic memories of racism in France because she looks more Algerian than French. She had turned up to work as normal at the gallery, and there in front of her, were Algerian Postcard Women, as part of Hamida’s work, looking at back at her. She was overcome and seized my hands as I walked in. The Postcard Women speak to us of our “now” and not just our “then.”

Hala Ghellali is a jewelry historian, who has been our expert for a few years now, helping us disentangle the confusions of jewelry and “props” to help us get to the bottom of who these Postcard Women really were. Hala is from Libya, and now lives in the US. She has a stunning collection of old Libyan photographs, postcards, jewelry and textiles, some handed down to her from her mother and her grandmother. Hala is also an artist, her moody deep blue cyanotypes of Postcard Women “caught” by Italian colonial photographers include glints of silver and gold to pick out heritage jewels that are wrought with poetry, songs, things held close to the body, the body of many histories. This knowledge and understanding lived on in fingertips and on tips of tongues. I packed away the Libyan waistcoat, or farmlet el-gamraat, that Hala tells me is embroidered in real silver threads, from the 1960s, employing a technique now rarely used. What knowledge and languages live on inside those threads and the hands that stitched them?

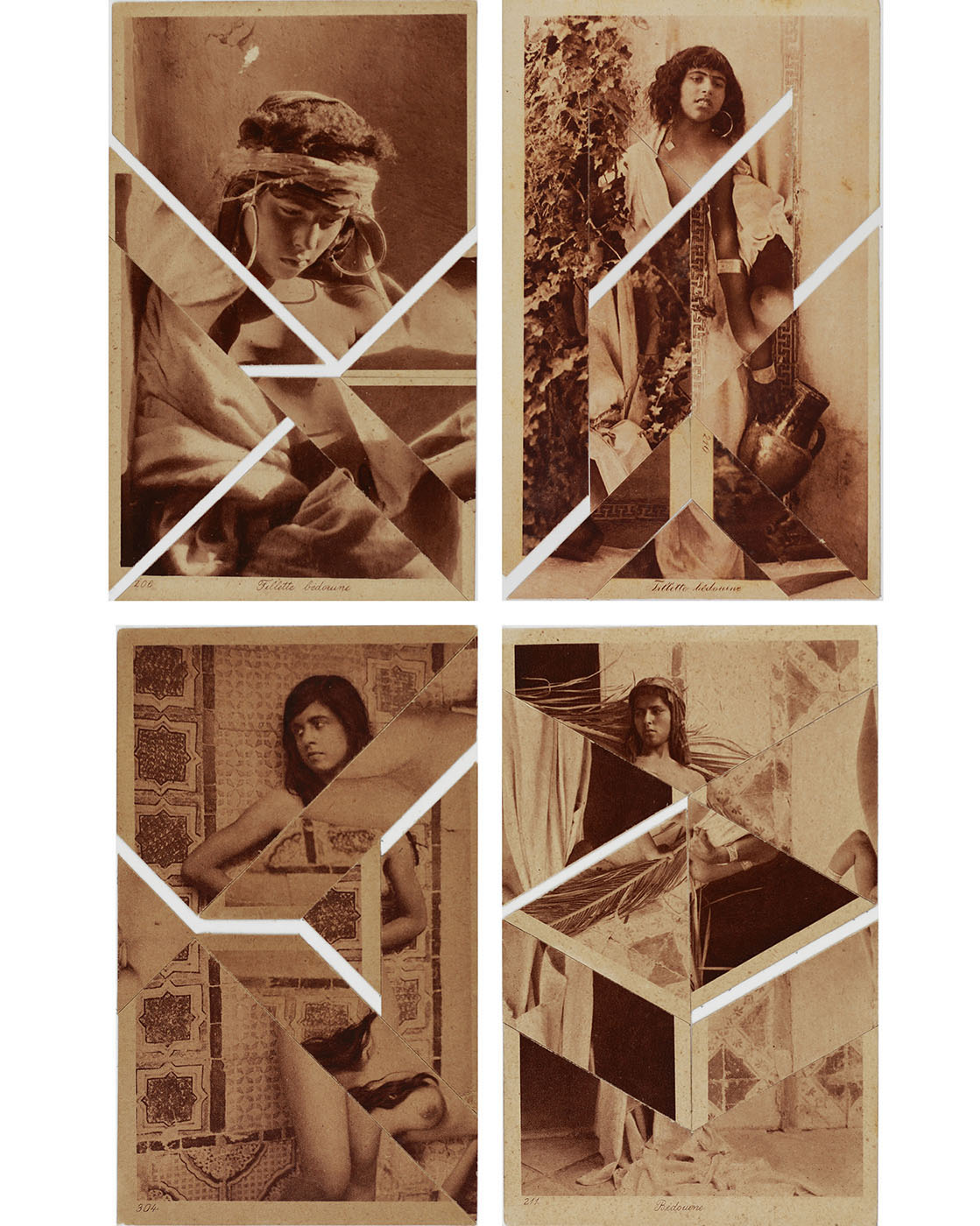

CritTeam, consisting of Eugenia López Reus and Miguel Jaime, are wife and husband; I didn’t know this until I met them in London this September. They are an artist and research duo that emerged in the UAE, where they were teaching in 2013. They are architects and artists and so much more. And what are two people from Barcelona, one part Cuban, whose ancestors fled Spain to South America, doing in a project about photographic representations of women from the MENA region? There is the more obvious, perhaps, connection of Moorish Spain and North Africa. But their story is even more fascinating and complex. I found myself saying, well, imagine that! They have ancestors who fought in the Rif war of 1921-1926, in Morocco. They found a few postcards in a Barcelona flea market, written by a soldier from that war, to his young daughter in Barcelona. He addresses her as Querida Nena, the name of one of three of their projects engaging with postcards of women from Morocco and Tunisia that featured in our exhibition as part of Phase II. This father, a soldier fighting for Spain in a “protectorate” in Morocco, wrote over 90 postcards to his daughter, calling the Moroccan women on the front “dolls.” He even wrote over their exposed breasts. Tender messages to his girl-child. Somehow Eugenia and Miguel tracked down all these postcards after having at first found only a few. Then there is their dedication to the use of radical ornament, using Nasrid tessellated patterns from the Alhambra to disassemble troubling images of underage nude Tunisian girls, photographed by Lehnert & Landrock studios. Their avant-garde work in opposition to Western Modernism inserts postcards of Moroccan women into the silhouettes of Matisse’s Blue Nudes, making visible the shadows of Orientalism and othering in Modernist discourse. You can read all about it in their chapter “Fighting Myths.”

Recently we had an exchange in our Imaginarium discussion group with a French man, whose collection of images feature in a book of violent images, Sexe, race et colonies, by Blanchard, Bancel among others. I will leave the reader to look up this book, which troubled us a lot at the beginning of our journey. But we decided not to deal with these images. Even the images we have are bad enough and we didn’t want to recycle trauma. He told us that we were only dealing with “soft” images. As a European male, who is he to define for us what “soft” trauma is? Coincidentally, during this discussion online, Stephanie sent me a comment by a Tunisian woman, talking about the distress she felt seeing underage Tunisian girls on postcards at a flea market. No one can tell us what we should or should not feel. Eugenia and Miguel dealt with these images of Tunisian girls in a poetic, protective and incisive manner, using the ornament of “Islamic Spain.” Just imagine that.

Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, a renowned academic and also an artist, is another extraordinary heroine who emerged from my collaborations and conversations. Her film the world like a jewel in the hand [sic] was screened at the exhibition, and it tells the story of imperial violence and plunder that ripped and continues to rip Algerian Jews away from their heritage as Arabs, as people invested and completely involved in a world shared by Muslim and Jewish Arabs and Berber/Amazigh people. Jewish silversmiths were making and using the same amulets as Muslims. Her epistolary essay to an unknown Algerian French relative, in our book, is a deeply personal and powerful revelation of how colonialism created “modern” as a progressive type in opposition to the “backward” Postcard Woman wearing her “traditional” clothes. She continues to search for her Algerian Jewish heritage through the physical acts of recreating jewelry that her ancestors must have once made.

Dr. Chamion Caballero is the director of The Mixed Museum, which is one of our supporting partners. (To get funding, I needed partners to pledge support and collaboration in various forms.) She is “mixed-race” herself, an awkward term we still often use (let’s not forget how the idea of race was a European pseudo-scientific invention), and she has single-handedly created an astonishing and important award-winning digital museum looking at racial mixing in Britain. The first of its kind, The Mixed Museum has explored mixed Black British stories and histories, and is now helping us bring mixed Arab and North African British stories to the fore. Many young mixed Arab and North African British men and women turned up to the Arab British Centre, which supported us by hosting our Imaginarium workshop. They came to share their stories, photographs and other things that matter. Mixed people can tell us about a British colonial and North African history that is deeply complicated and largely untold.

Our project has unearthed and unleashed what we already know and knew. And what of anti-black racism in the MENA region? We tried to address this. People in our communities are in denial. They want to complain about the violent histories of colonialism, and so they should, but when it comes to thinking about our own violence to those we have designated “other,” we develop selective hearing. The term “Arab” is one that causes a lot of concern. Any label or term inevitably excludes people. We North Africans are not sure if we are really Arab. What Black histories do we hold in our bodies that are being erased and forgotten? Like the Zar healing ritual for marginalized women, which comes to Cairo from Nigeria, where I grew up, and from Ethiopia and from Sudan. Sudan is the most vital topic we need to turn to next. Yasmin Elnour is a young Sudanese artist, architect and recent collector of postcards from Sudan, who is using Nubian symbols, Kushite monuments, and ancient Sudanese iconography to celebrate femininity and create new visual languages. She happened to be over from Khartoum for a few days. Imagine that. I invited her as our guest to come to the gallery in Camden to share this incredible collection of troubling postcard images. BBC Africa came and filmed us on our last day.

We have to end our story here, for now. There is much left to say and so many heroines in our story, including the pioneering Dr. Reem El Mutwalli of The Zay Initiative, who gave us a platform from which to speak, and shared her beautiful Iraqi/UAE story, “Our Narrative: a trilogy through dress,” as a guest contributor in our exhibition and book.

It is hard to do justice to all the complexity and layering in our work. You cannot reduce us to this or that group. We are MENA women and not. We are boundary crossing and boundary breaking. I wanted to bring bodies together that might not usually meet. I think I did that.