Colorism in Syrian Communities is Tied to Centuries Old Endemic Anti-Blackness and Internalized Colonialism

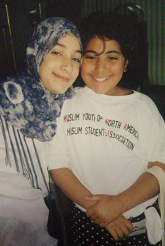

Banah Al Ghadbanah

I am eleven years old, standing in an elevator at a U.S. Muslim conference. I am going upstairs to help my mom’s friend with some babysitting. One person in the elevator asks, “Where are you from?” In a congenial kind of mutual Muslim-recognition way, someone else suggests “let’s all take a guess!” One person says “Pakistan!” The next person says “Mexico!” Another person says “You must be Egyptian?” I respond, “Good guesses, but I’m from Syria.”

“Syria? There’s no way you’re from Syria! I’ve never seen anyone who looked like you from Syria. There’s no way you could be a real Syrian.”

I used to get this a lot: “there’s no way you’re from Syria!” It is code for: “I’ve never seen a brown-skinned person, a non-lily white person, who is from Syria.” The dominant representation of Syrians is that we have some kind of peachy-skinned, green-eyed, light brown hair phenotype. Even other (lighter) Syrians would not believe I was from Syria. “You must be Indian! Egyptian? Moroccan? Not Syrian.” These guess-her-ethnicity debates always confuse me, because I know plenty of brown-skinned Syrians, browner than me. But why are we never represented? Why is there an image of the “Syrian” as wanting-white, close to white, and what does it mean about class, race, and the context of our migrations, particularly those of us who come from exile and forced migration?

I served once as a volunteer for a refugee relief program in Amman, Jordan. A group of white women played “guess where she’s from” in English, not realizing I spoke English too. “Wow, she could be Afghan.” “Do you think she’s Syrian? There’s no way.” “She’s so beautiful.” “I wonder what her story is.” I turned around and spoke in English to them in a middle-American accent and it scared them shitless. In those days I wore hijab, which added to their shock. Another time I was volunteering for a refugee organization in Greece when one of the white women said, “Imagine if you had blue eyes. I want my daughter to look just like you, have your skin color, but with blue eyes. That would be so beautiful.”

Growing up as someone whose skin ranged from deep tan to light caramel, life as a big belly brown girl was pretty carefree until someone made comments on my body and it not being acceptably “Syrian” enough. To make matters more complicated, I rarely saw other Syrian Americans who came from fellahi (farmer) backgrounds such as my father’s, or whose family had to flee because of the regime. I didn’t grow up around much Syrian community other than family, and was often suspicious of other Syrians because they could have pro-regime ties that could endanger my family.

As a Syrian, I never find myself in representations of Syria, in literature, in poetry, in movies. Even our children’s rhymes praise white features: “Sha’ra wa beida min tartoos, mab takil ila makdoos—She’s blonde and white and from Tartus, doesn’t eat anything but makdoos.” There is a hyper-obsession with wanting a Syrian bride who is “white” (“bayda”) and not “samra.” “Samra,” like “morena” in Spanish, means darker, used as both an affectionate term, an exalted term back in the 1950’s-60’s in songs by Abdel Halim and Fairuz to praise the beauty of the “dark skinned” Arab, and also as a derogatory term.

When I lived in Tunisia for a period, a man on the street asked me where I was from. I said “Syria” and he responded “how much?” Meaning how much is my price for sex work, because darker skin coming from Syria with no hijab combines the gender and racial fetishizations into the association that I could only be a “samra” Syrian woman if I was a sex worker. It is important to not perpetuate any form of stigma against this line of work, as sex workers are constantly under attack. And in fact there are centuries old pre-Abrahamic ways of being in our cultures that understand and revere sex work as a beautiful community role and as a spiritual practice. But in this context the man’s comment was rooted in racism. In North African countries, Black women coming from Nigeria and other West African countries are often at risk for human trafficking and sex trafficking as part of a deeply racist anti-Black system that hyper-sexualizes darker-skinned women and literally profits from their bodies in ways to which they do not consent, with social attitudes that do not bother to distinguish between consensual sex work and horrific human trafficking. To this man, I wasn’t a “proper” (“white”) Syrian woman, who would be considered in the top rank in the Middle Eastern hierarchy of gendered racial whitewashed “preferences” for marriage.

In Tunisia I was stopped at a checkpoint. The military police didn’t believe I was American. “Clearly she looks more Arab than me, there’s no way this passport is real.” It was Identity 101 and these men with guns were a bit dense. It was past midnight and I was scared. I called the director of my program and he vouched for me but they wanted to confiscate my passport anyway. Another time, my siblings and I were travelling alone to Jordan when the officials harassed us, “There’s no way you’re American. Clearly these are fake. You’re lying. In the photo you’re not wearing hijab, but in person you’re wearing hijab.” The subtext is that light-skinned Syrians can be believed to live abroad, but there’s an assumption that browner-skinned ones don’t have that mobility and therefore are “lying.” Because of our U.S. passport privilege, we got past the outer checkpoints but were still harassed by those inner border officials. They brought the supervisor who mocked our Syrian accents and finally they let us through. My cousin who does not have our U.S passport privilege, was stopped at the outer gate of the airport while dropping us off. The guards assumed his identification was fake, and detained him underground in the creepy airport prison for a week. He too is “asmar,” or darker.

When the Syrian revolution began in 2011, the regime’s displacement would eventually cause over 13.5 million people to flee. As a result for the first time in my life, I began to meet other Syrians, outside of my family, who were just like me. I met so many brown-skinned Syrians. And maybe the reason I couldn’t find them before is, in part, is because of which side of the struggle against the regime that Syrians came from. Many of the more resourced diaspora Syrians to whom I had previously been exposed were from cities, middle class, and bore lighter-skinned privilege. And while there is no simple correlation with skin color, the uprising began in rural areas such as Deraa and was strong in northern regions such as Idlib and Raqqa, and many of the refugees I saw were darker Syrians. In fact, while I was working with different groups of recently displaced Syrians, Syrian moms would come to me and ask to speak with the daughters about the colorism they faced, to affirm them, and to validate their experiences.

At the same time, there are refugee/migrant people in my own family who had to flee, and who have the palest skin and blue eyes, who survived chemical weapons attacks, and that experience is still also very Syrian. So it’s much more complex than a binary. There are a lot of unspoken class lines where many Syrian doctors and professionals who left on student visas tend to come from upper middle-class families with light skin. But my family also benefitted from the student visa movement, so again the binary is not all black and white. Another layer is that many Syrian women who have endured imprisonment and all kinds of horrific treatment in Syria are dismissively called “white,” as a way to undermine them when they bring up issues within the movement. This label is deployed against them by white-looking Syrian men who would still never listen to brown-skinned people like me even though they mobilize my phenotype for some kind of authenticity measurement to invalidate others.

For the longest time, in the wake of an ongoing revolution and subsequent genocide, I felt like addressing other problems within the Syrian community, such as colorism, would be a “distraction.” With chemical weapons attacks, the Assad regime and its Russian allied airstrikes burying children in the rubble of barrel bombs, the ongoing protests and court cases against torture in prisons, I never felt like it was a “right time” to bring up colorism. But the Black Lives Matter movement sparked important conversations across the world about deep-seated colorism rooted in anti-Black violence. I know now it is all connected.

I think it’s important point out that, on the spectrum of people of color, I still deeply benefit from non-Black privilege at every turn. It is important to remember that. Light-skinned people are more likely to receive job interviews, and receive preferential treatment in every facet of life.

In non-Syrian contexts I have been mistaken for white, Native American, mixed-race/biracial Black and white, Central/Latin American, Jewish, Indian, and so many other things. My racialization often depends on who is looking at me. I want to share what my story is like in a Syrian diaspora context where it hasn’t been spoken about enough, and I hope that others feel called to share, but I know that racial ambiguity is also a deep privilege rooted in anti-Blackness.

From 2011-2015, I attended a historically Black college where Black students stood in solidarity with Syrian liberation. Thanks to Black feminist visionaries like Beverly Guy Sheftall and M. Bahati Kuumba at the Women’s Center at Spelman College, we students did projects in solidarity with Palestine, and created the first Students for Justice in Palestine at a historically Black college. Each summer, in my family’s microcosm of a Syrian society in Amman, I would have important conversations with community members about white supremacy, colonialism, and anti-Black violence in the U.S. And yet summers with my extended family always began with the question, “Why are you so dark? You’ve been in the sun too much. How are we ever going to find you a husband?”

After that first round of “Why are you so dark?” from my relatives, neighborhood women would come in and ask the same question. Last time I was there, I had a conversation with two of my aunts that the reason those constant comments bothered me so much is because they are rooted in anti-Blackness. I told them it reminded me of things white people in my southern hometown in the U.S. would say to me growing up about my skin being “dirty.” I also felt frustrated because on a conceptual and intellectual level, people I know in the Middle East seem to understand white supremacy and police brutality, but still police each other on skin tone internally.

“But I faced racism as a Syrian in the UAE and I know what that’s like,” one of my aunties replied. “They would line us up, non-Emirati nationals, and the others. Syrians would always get singled out. We’re not racist against dark skin at all! We have so many African friends. Their skin is so beautiful. But God made us originally white, you’re an exception, but if you stayed out of the sun you’d be white too.”

Another auntie retorted, “there’s no way we can be racist, you are American and we are Syrian. We’re only commenting because you should take care to be out of the sun.”

I told her, “You are colonized in the mind, 3mto. You always talk about Israel and how they colonized us, but you are being the colonizer right now. You are showing me that you value white skin, even if you have token Black friends to prove otherwise. And I get to live my life and be in the sun.”

“What? Me? I have to think about that one. Colonized in the mind.” She actually began to think about it. Recently she sent out a video on our family WhatsApp group by Afro-Palestinian actress Maryam Abu Khaled who shared how colorist comments can be deeply psychologically damaging and are rooted in anti-Blackness. I’m glad she’s finally coming to understand this, at the expense of years of my girlhood self-esteem and her deep-seated unexamined privilege.

Later that same visit, my grandmother, brown herself and experienced from decades working in the fields and harvesting in the sun, was grinding kishik on the roof. My aunt commented, “Oh no mama! Look at how dark you’ve gotten.” My grandmother winked me and said, “it’s Banah who we have turned brown. Samoora [brown girl]! And we’re bringing her back to her roots.” For Teta, our skin color is a source of pride, to come from a people who work in the earth and spend time in the sun. Teta always tells me, “you’re the farthest from the farm but you look the most like a village girl.” But my grandmother is in the minority, especially in her generation. I have a random ancestor with red hair and white skin whom my family on that side points to as proof of our “white” looking “source.” One summer, a group of family members literally stood around me commenting on how dark I was and how I look more like a refugee than the actual refugees in the family. My uncle’s German mom took me aside and said, “In our culture, we sit in the sun all day just to be darker. I wish I looked like you.” At every turn there’s nowhere constructive to go. I wanted to say, you don’t know what it feels like to be me, so please stop wishing you had something you’re not. Just be you and be that.

To the other side of my family, who are middle-class Damascenes, the bigger issue is my “fellahi/peasant tendencies” that clearly come from my dad’s side. Sometimes a “country” word would slip into my Arabic, and my grandpa would say, “never say that again around me.” The way I made my hummus was like a peasant, or the way I inflected certain words. My grandfather is outspoken against anti-Blackness and admonishes anyone who didn’t understand that African American people have been though 400 years of ongoing slavery. He was educated by Black Muslim men in his community when he first came to America, and their labor of educating him on these issues is important to acknowledge—he became politicized in new ways and taught his children the lessons they taught him about anti-Blackness and police brutality in this context. My grandmother on that side is Algerian-descended and she has light skin and green eyes. I never was explicitly made to feel “different,” but it was still made clear that I was. I don’t know how to put into words what it feels like when you are constantly surrounded by people who are whiter, thinner, and considered normatively attractive, and there are very few people like you on one side of your family. Even though I wasn’t mixed race, I felt kinship with those who were, as a brown-skinned “Other” in a family of white-passing people with Syrian and North African ancestry. It’s hard when no one thinks you’re your mother’s daughter. When you want to look like her growing up and have her green eyes and light brown hair. When people say “I wish you looked more like your mother.” When all the brown-skinned Syrian men are marrying whiter-skinned women. A parent can do everything in her power to affirm her browner daughter, but one or two comments from community members can make it all come crashing down.

I remember being five or six years old and my cousin and I were jumping on my aunt’s bed and looking in the mirror at ourselves. “Why did God make me ugly?” I said to her. “Everyone says you’re pretty but no one ever says I’m pretty. It must be true. God gave me these bags under my eyes and I’m cursed.”

I don’t know who told me, because my mother definitely tried her best, but I had already heard I was ugly and internalized it from somewhere that the color of my skin was a problem. Most likely it was the white dominant American society I was shuffling back and forth between, but it was certainly coming from the Syrian community, too. Today I see younger cousins with brown skin in the summertime being admonished the same way I was a kid (“why are you so dark?!”) and it fills me with rage. I want them to feel proud of the way they look and know they are part of our heritage and part of our culture. I want them to feel like they have a right to speak.

Some of us in the Syrian community have always been the butt of jokes, socially made to feel unacceptable, through “light” comments that over time, we are told are “not a big deal.” They are deeply intertwined with regionalism, classism, and which side of the Syrian struggle we stand on. The irony is that I am very privileged on the spectrum of Syrian experience, having US citizenship, which many do not, and having access to higher education. It’s not a simple binary. And yet no amount of privilege erases my brown skin. I have been thrown out of dress shops in downtown Amman because I was told I was a “dirty Syrian” who wouldn’t buy anything, and told I’m a “dirty Mexican” by white girls while growing up on the other side of the ocean, in the U.S.

My non-American and my American-based Syrian relatives are both always telling me I’m obsessed with racism as a result of being in America. They tell me we don’t have race in Syria in the same way, which is true—it’s different: we have regionalism, classism, sexism, sectarianism.

But if we don’t have race, then why do we have racism? If there is no race, then why is it a problem that I’m darker? Why are brown and Black Syrians rarely shown on Syrian media? Why is the “white” Syrian bride so coveted as a beauty standard? There is so much “racial” ambiguity when it comes to Syrians because our ancestry is at the crossroads of thousands of years of migration between Africa and Asia. There are uncles in my family with 4B hair, white skin, and wide noses, and ones with blue eyes and rich bronze brown skin, literally brothers in the same family. One of my grandmothers could be mistaken for Nubian, and uncles in the family have been racialized as African American while navigating the streets of DC. I have cousins whose parents don’t know how to take care of their hair and began straightening it at age three. I have cousins with pale skin, straight blond hair, and blue eyes. I have cousins with deep brown skin, unibrows, and brown eyes. Because my skin color varied so much growing up, I could tell right away as a child that I would be treated better when I was lighter. When I was a few shades darker, I would be disciplined more at school in the U.S., seen as disruptive, made more of a token. I knew early on that this was fucked up and I could physically feel the difference. I have been mistaken as Mexican, Indian, Moroccan, mixed-race, Native American, white, biracial, but never Syrian—because no one knows what that is yet.

At the same time, despite the flexibility and complexity of our racialization in my family, our lived experience is not that of Black Arabs in the Middle East, nor of Black non-Arab Middle Easterners, who are constantly put at the margins of discourse on the Arab world and subject to a horrifying range of anti-Black treatment while in the Middle East. There are important conversations coming to the forefront about the treatment of Afro-Iraqis and Afro-Palestinians as a results of years of their protests and advocacy. What I experience is only a fraction of that as a brown-skinned Syrian. I still experience and deeply benefit from light skin privilege in the spectrum of people of color, at every turn.

In our revolution, we must work towards dismantling the oppressor who lives within each one of us. We have these conversations so that one day we may rebuild a Syria that celebrates every member of its society. In Syria, part of our revolution is to dismantle oppressive structures that correlate with the interpersonal microaggressions that enforce them. We must envision a future Syrian society that is no longer obsessed with lightness and that does not praise someone for being closer to white. In a future Syria, I hope that lighter-skinned Syrians may understand and speak up when they notice colorism against their darker-skinned siblings, the way my mom, sister, and some of my cousins have always done. We will build a society that fundamentally questions the premise of a programmed fear of darkness. There is so much we can do once we address these issues. We can build a Syria where Black and dark-skinned people don’t get exotified or made to feel like an exception. Where Kurdish, Alawite, Ismaili, Turkman, Yazidi, Circassian, Druze, Armenian, Assyrian, and all other sects and ethnicities are not erased, disrespected, or pit against each other in the name of pan-Arabism. In a future Syria, we will build a society without authoritarianism, and more importantly, among ourselves, we will decolonize our authoritarian attitudes and policing towards each other. In order to build a better world for our children and their children we must first acknowledge that these things exist and they cause harm, not just on an interpersonal level but on a structural level too.

As Audre Lorde put it in her 1980 essay, “Age, Race, Class, Sex: Women Redefining Difference,” each of us must begin the difficult work of reaching inside ourselves and removing the loathing of difference that lives there. I want a future Syria where disabled people feel welcome and centered, where children are safe, where all ethnoreligious groups and races are represented, where queer and trans people can have an active voice in shaping our society, where women can participate and be valued, where young men and women heal from the trauma of prison brutality, where we learn each others’ histories. I want a future Syria where we acknowledge our own participation and proximity to centuries of anti-Blackness in the Middle East via the Arab enslavement of East African people and the Indian Ocean economies of enslavement, and the present iteration of that in the kafala system wherein Indian, East African, and other migrants are in forcible servitude with little freedom in the Levant. I want a future Syria where we dismantle the regime, and everything like it. One where we no longer weaponize constructs of “Western” and “Eastern” to invalidate each other’s lived experiences, but recognize the complexity of our lives as a community that is now dispersed around the world in a new way. I want to see little dark-brown-skinned Syrian girls feel truly accepted and encouraged to play in the sun and live out their fullest, brownest lives.

Es increíble el sesgo ideológico que hay en este artículo, un asco!!