Nadjib Berber

Translated from the French by Susan Slyomovics

My name is Nadjib Berber and my cartoonist name is Nad. I was born in Tlemcen, Algeria and grew up in Argenteuil, a suburb of Paris. My family returned to Algeria a few years after independence. In 1992, I left for the US where, after a stint in the Boston area, I wound up in Los Angeles.

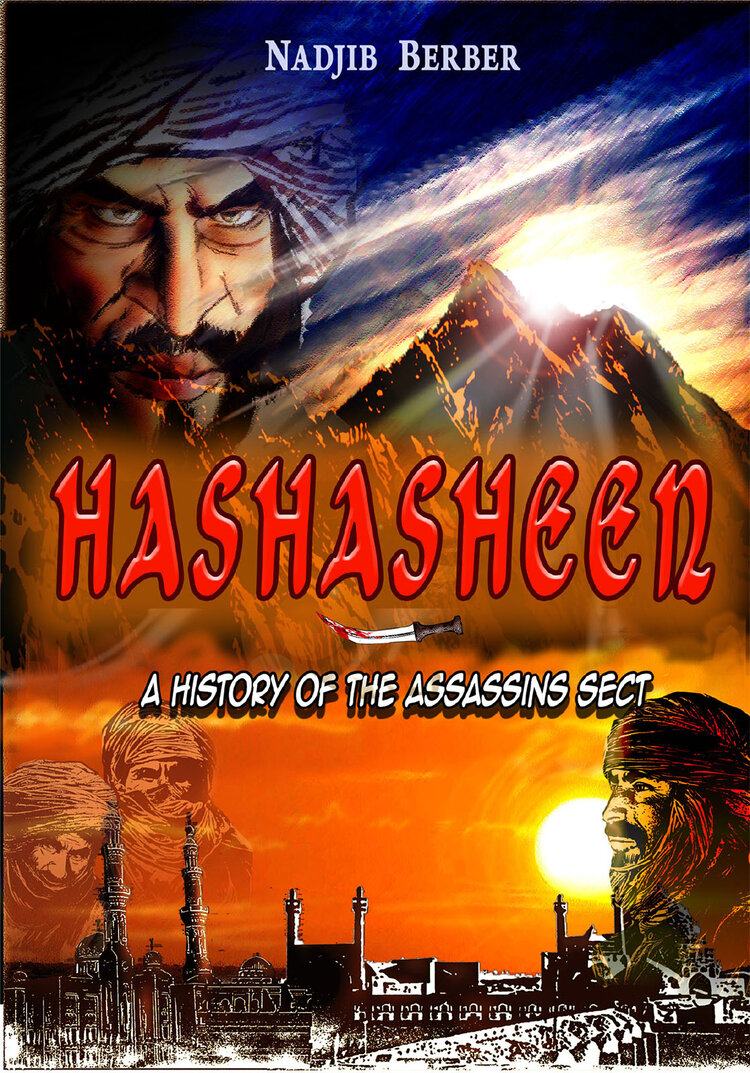

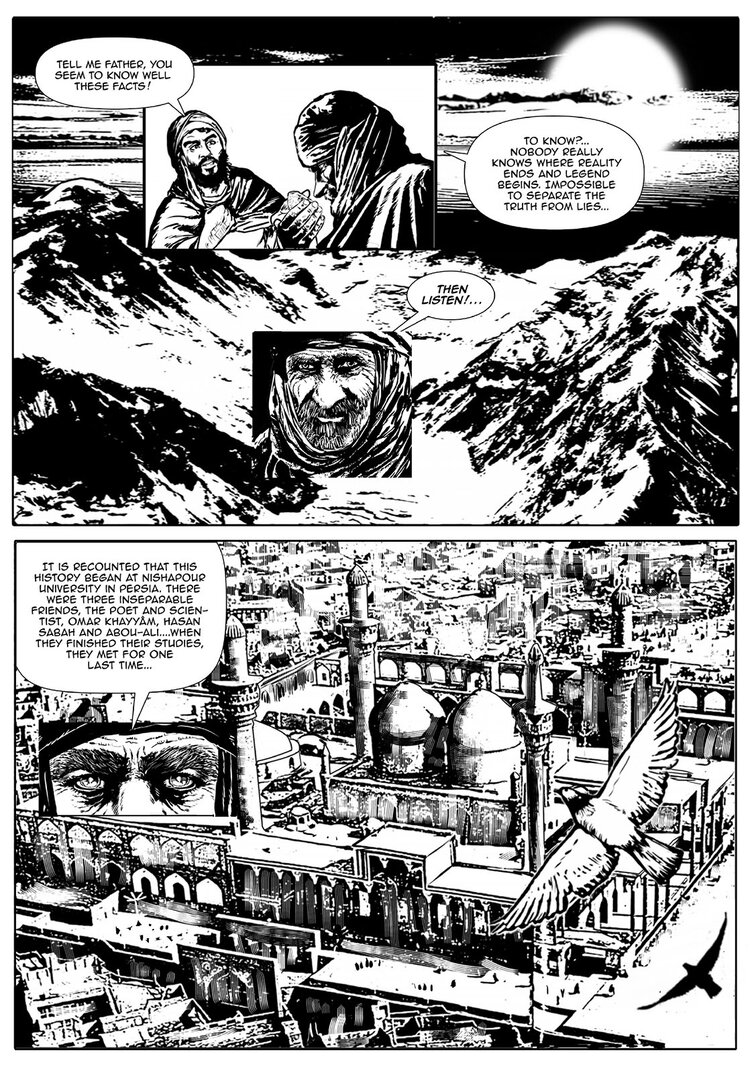

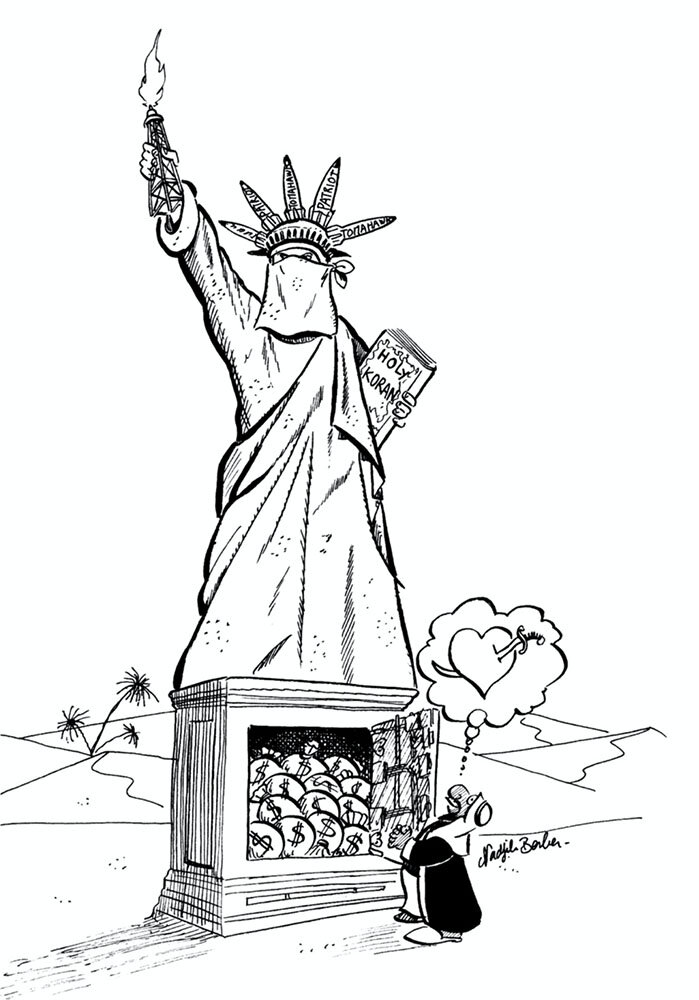

When I lived in Algeria, I was based in Oran, Algeria’s second city, where I drew comics and later political caricatures for several Algerian newspapers. I also collaborated with Kaous Kouzah (Rainbow), a Tunisian magazine that published cartoons from 1984-89 for which I drew children’s folktales and one-page gags. By the way, our comic book readers follow graphic frames from right to left just like the Arabic script. Especially in the late 1980s and early 1990s, these were pivotal years for freedom of the press in the post-colonial history of my country. During this period, alongside the new multi-party policy, newspapers and journals flourished, creating a significant group of political cartoonists, most like myself coming from the world of comics and graphic novels. For Revolution Africaine (established February 1963), I produced some covers and a weekly full-page of political cartoons entitled “Psychosis” (Psychose). My 1991 cover for Revolution Africaine compared Algeria’s multi-party elections to Native American attacks on the US cavalry holed up in their forts, the latter embodied by then President Chadli Bendjedid. Psychose was my political cartoon strip in answer to the question whether Algeria’s numerous political parties could form a coalition government. I also collaborated with the satirical Arabic-language journal Es-Sahafa, which means “journalism” but is also a pun as the two words Essah-afa also mean “truth is a scourge.” In the slideshow below you’ll find an example of my caricature of SaïdSadi, an Algerian politician who appears next to the newspaper masthead. For twenty years, Algeria was the preeminent country of comics in the Maghreb and Middle East. At the same time, I collaborated with Kaous Kouzah, which was disseminated throughout the Arabic-speaking world. Since moving to the United States, I published some English-language political cartoons, sometimes without words. After September 11th, 2001, I found myself returning to an earlier project that I had been working on in Oran in the early 1990s, entitled The Old Man of the Mountain. As I told a newspaper at the time, “The events of September 11 and their impact on American public opinion have pushed me to resume my project ofanalbum on the sect of Nizari Assassins, founded by the ShiiteHassanSabah to fight those he called usurpers, theSunni Seljukswhodominated the Muslim world at the time.” TheNizari, an offshootof an Ismaili Shia sect,acted asthe sworn enemies of the Ottoman Sunni empire. I noted the similarities of this sect with the organization Al Qaeda, the plotters of the attacks against the Twin Towers of New York, particularly in terms of the strategy of terror adopted and violent actions taken. With a handful of devoted men, Hassan Sabah seized a castle in the mountains of Elbrouz, Iran. Within this impregnable fortress of Alamut, he trained an order of warriors — fidayîn, those who sacrifice themselves. His faithful followers become a shadowy army, decisive, invincible, prepared to sacrifice their lives to kill the designated enemy, often a dignitary of the empire. This sect made all the princes of the Middle East tremble in fear throughout the period of the Crusades for over 170 years. I am currently working on the tale of the “old man of the mountain” first in French as Hashasheen (cover and interior art below) and then in English translation for publication in the United States. As I told an Algerian newspaper, “The American comic book market is dominated by ‘fanzines’ devoted to superheroes. It’s a mass-market production. There are few quality albums, technically and in terms of illustration, as there are in Europe. An album like mine may possibly interest ‘underground’ distributors, but the experience deserves to be tried.” In the last few years, I have collaborated with Aomar Boum, an historical anthropologist of Middle Eastern and North African minorities, on a graphic novel titled Undesirables that traces the story Hans, a German Jewish journalist who fled Berlin in 1933. This graphic historical novel highlights the impact of WWII outside of mainland Europe through the stories of refugees in North African Vichy camps. Hans is a composite character and represents the tale of several historical figures including the experience of Sophie, Sigmund Freud’s granddaughter, in Casablanca. In this work,Hans the main character exemplifies the story of thousands of European refugees, who fled Nazi Germany and were sent by Vichy authorities to North African labor camps to work for the trans-Saharan railroad networks connecting the Sahara to the Mediterranean Sea. While the classic American film Casablanca references some of these refugees and labor camp internees, our graphic novel attempts to shed more light on this forced migratory journey and the precariousness of the war. Many theories and histories have engaged with concentration camps in the European context. Hans’s travails inject new perspectives about the range of detention and incarceration throughout North Africa by relying on archival data to highlight interactions between European Jews and native Jews, Spanish Republicans and Vichy authorities, the indigenous Muslim population and Jews (both European refugees and native North African Jews), guards and internees, and more. Undesirables is an attempt to expand the role of comics in depicting the trauma of WWII beyond mainland Europe. It will be an addition to other comics such as Karen Gray Ruelle’s The Grand Mosque of Paris: A Story of How Muslims Rescued Jews During the Holocaust and Didier Daeninckx and Asaf Hanuka’s Carton Jaune. Meanwhile, even though I’ve carved out a new life for myself in the United States, I have always remained connected with my compatriots, including those based in France such as Slim, Farid Boudjellal, Larbi Mechkour, Lounis and many others.

Translator Susan Slyomovics is Distinguished Professor of Anthropology at UCLA and writes about visual anthropology in the Middle East and North Africa.

Revolution Africaine

My 1991 cover comparing Algeria’s multi-party elections to Native American attacks on the US cavalry holed up in their forts, the latter embodied by then President Chadli Bendjedid.

Es-Sahafa

The satirical Arabic-language journal Es-Sahafa means “journalism” but is also a pun as the two words Essah-afa also mean “truth is a scourge.”

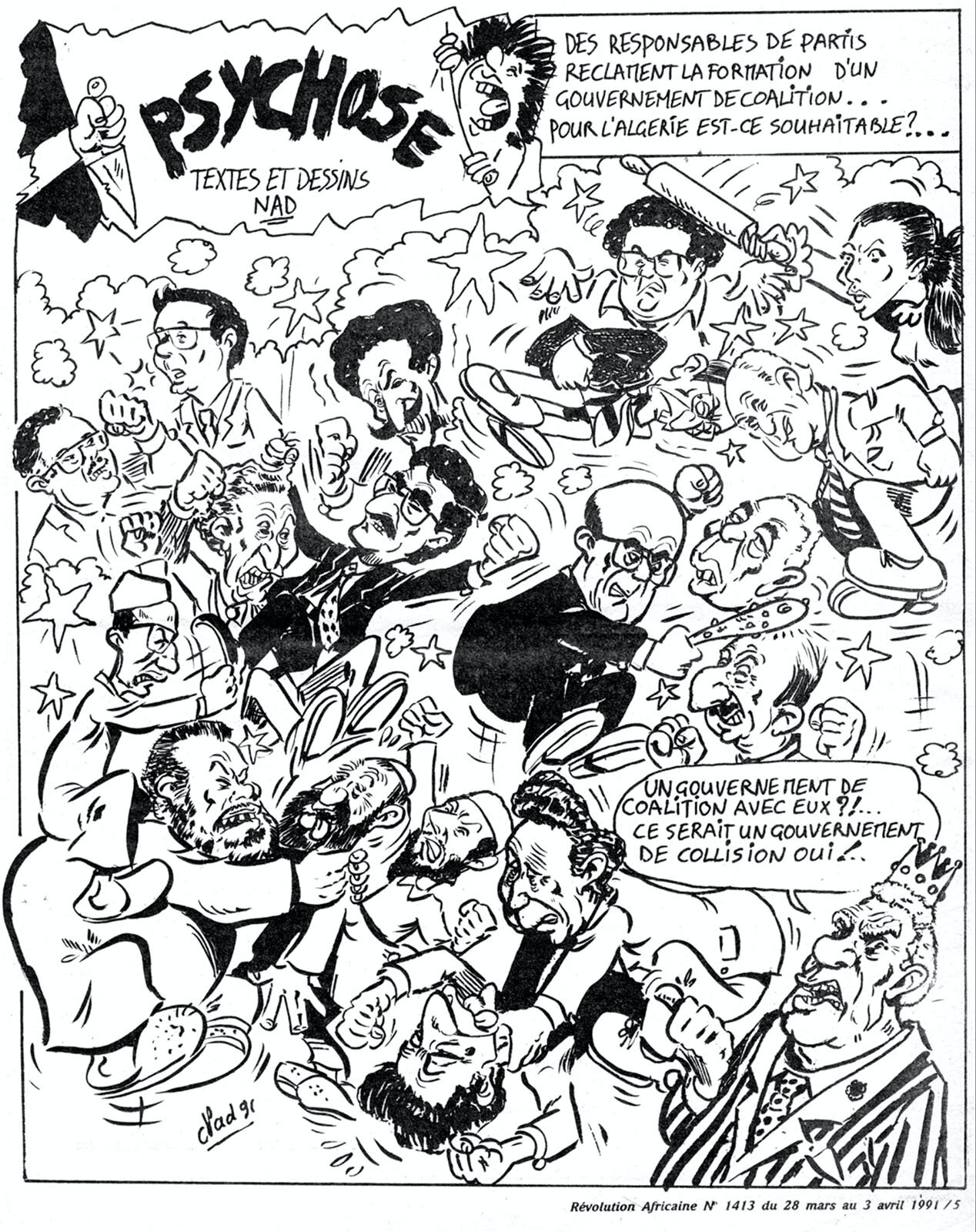

Psychose

My political cartoon in answer to the question whether Algeria’s numerous political parties could form a coalition government.

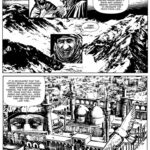

Undesirables

Page 66 from Han’s story…

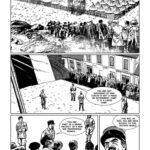

Undesirables

Page 69 from Han’s story…

Un vrai amoureux de la bd, un artiste, un ami qui nous a quitté ce 5 mars, je n’avais plus de nouvelles de Nad depuis quelques temps. sachant qu’il était soigné d’une longue maladie je n’ai pas osé l’embêter avec mes appels intempestifs, la nouvelle m’a beaucoup touché, repose en paix mon ami et rendez vous au festival céleste de la Bande Dessinée. Paix à son âme.