Algiers, Third World Capital, Freedom Fighters, Revolutionaries, Black Panthers by Elaine Mokhtefi (Verso, 2018)

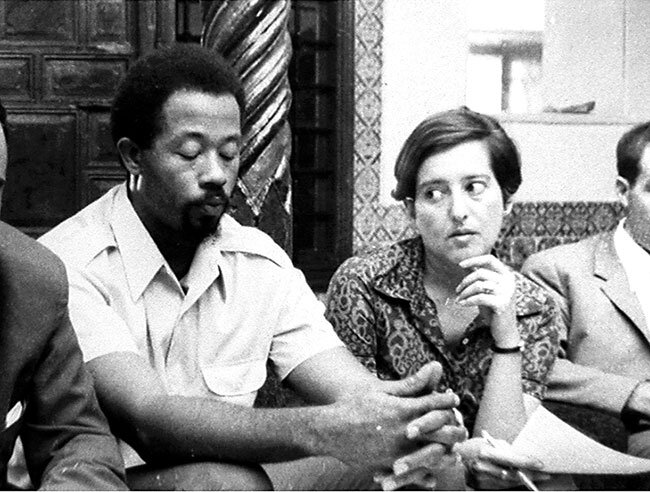

Anthony Saidy

At 23, motivated by lofty ideals for world peace and justice, New York native Elaine Klein settled in postwar France, where she found work as a translator and interpreter for international organizations. In 1960 Klein got involved with a New York-based group that was part of the Algerian National Liberation Front, or FLN. They lobbied the United Nations in support of Algeria’s government in exile, working for Algeria’s independence from France. Klein soon found herself swept up in the Algerian Revolution and gave it two decades of her life, marrying the Algerian intellectual and liberation war veteran Mokhtar Mokhtefi (author of J’Étais Français-Musulman). In Algiers, she got attached to Black Panther Eldridge Cleaver, for whom she performed various tasks and missions, and was ultimately deported for refusing to be a spy for the Algerian secret police, having long known of their use of torture.

In September 2018, at the age of 90, she spoke in L.A., when I bought and soon devoured her book. Algiers, Third World Capital would have to appeal to someone like me who had lived through the 1960s and 1970s, in close touch with domestic and international ferment.

While Elaine Mokhtefi worked devotedly for the Black Panthers, the men who ran it were, it turned out, deeply flawed. They were not equal to the task of keeping their movement afloat in the face of the U.S. government’s repression. The college activists who started the Black Panthers, Huey Newton (1942-1989) chief among them, were joined by a self-taught ex-con and author, Eldridge Cleaver (1935-1998), who never severed his criminal ways. Famous for his 1968 book of essays, Soul on Ice, Cleaver escaped to Cuba later that year after a shoot-out with police in Oakland, but Cuba didn’t really want him and sent him to Algeria. His group there enjoyed a privileged life in an “embassy.”

Elaine Mokhtefi was invaluable to all of them, as no one was learning French or Arabic. She allowed herself to be used, presumably glad to associate with revolutionaries. One day Cleaver came to her office and confided he had just murdered a comrade whom he called a thief. Later she learned that the victim had dallied with Cleaver’s glamorous and masochistic wife, Kathleen (now a law professor). That Cleaver was a notorious serial adulterer did not enter his equation. Did Elaine turn him in to the police? La. She pointed out that he was beating his wife, and accepted his macho reply that some women liked that. Later she was a Panther courier and arranged for false passports doctored on site in Algiers by a visiting member of the Baader-Meinhof Gang. She chronicles the Panthers’ downfall after a very public feud between its two honchos. She betrays no qualms about her personal responsibility. Mokhtefi appeared for half a minute in the film Battle of Algiers, but in her book sheds no light on the genesis of that classic.

Expelled by the nation to which she had devoted her life, she brought her husband to the US, where he read aloud from the Koran after the death of Elaine’s Jewish mom and survived till 2015. Elaine carries on.

Her account flows well and is at times fascinating, despite the occasional typo. The book would have benefitted from an index, where you might have looked up her Rolodex of celebrity revolutionaries and misfits, from Stokely Carmichael (1941-1998, who dropped his American girlfriend for Miriam Makeba; when he split from the Panthers, Cleaver denounced his racialism); Frantz Fanon (she ridicules the story that he died in care of the CIA—but how did he get entrée to Bethesda Naval Hospital?); Ahmed Ben Bella (she was a friend of the beauty who was commandeered to marry the deposed and jailed ex-president); Houari Boumedienne (who took power in a coup which the people were too weary to resist); and current president in his dotage, Abdelaziz Bouteflika.

For a deep analysis of failed revolutions, you must look elsewhere.

Anthony Saidy is a retired physician and international chess master, as well as an author of several books on chess, and the novel 1983: A Dialectical Novel.