Upon their independence, Moroccan, Algerian, and Tunisian governments turned to the Global South and offered military and financial aid to Black liberation struggles. The new book by Paraska Tolan-Szkilnik explores the journey of a group of North African intellectuals, artists, activists, and writers, who struggled to find a way to envision a new postcolonial future.

Maghreb Noir: The Militant-Artists of North Africa and the Struggle for a Pan-African, Postcolonial Future, by Paraska Tolan-Szkilnik

Stanford University Press 2023

ISBN 9781503635913

Tugrul Mende

The new book by Paraska Tolan-Szkilnik explores the journey of a group of North African intellectuals, artists, activists, and writers, who struggled to find a way to envision a new postcolonial future. One of these intellectuals was Abdellatif Laâbi, who was imprisoned for his writings.

Abdellatif Laâbi belonged to a group of people whom author Tolan-Szkilnik dubs the Maghreb Generation. She gave them this name because of the central role the Maghreb played in their political and artistic evolution. Rabat, Algiers, and Tunis were central to their writing, painting, and film directing in which they debated the future of a postcolonial Africa. They created both a network and a cultural infrastructure in which they discussed matters that were important during their time. They started as an artistic and literary project but became politicized during their activities as a result of their engagement with several revolutionary movements in Africa and beyond. It is important to note that research about Pan-Africanism and the Black Atlantic rarely includes North Africa. This is where Maghreb Noir fills an important gap, with its concentration on the Maghreb from the 1950s through the 1970s, with a view on transnational, Pan-African activism.

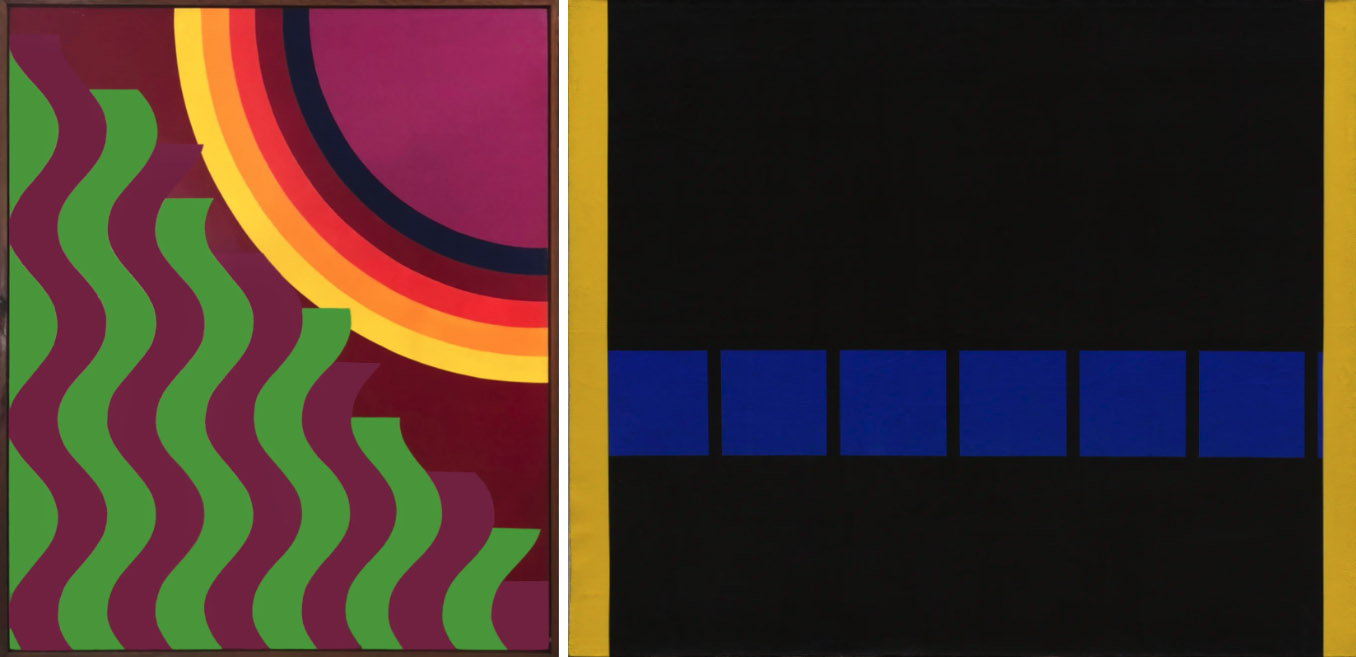

It is clear from the book that artists and literati played a crucial role in the dissemination and contribution to the Pan-African thought in the Maghreb. Laâbi, who continues to be a very prominent writer to this day occupies a central place in this endeavor but Tolan-Szkilnik writes a larger history of artists and literary figures who participated in this project by tracing the myriad circulations, publications, and productions of their writings and films through the events of the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s. She follows the artists as an attempt to better understand their world within and in interaction with Pan-Africanism during this period. To understand the work of these artists, Tolan-Szkilnik relies on a variety of print materials, interviews and films. Consequently, she reveals that the artists were part of a larger group during those days, encompassing a wide network of intellectuals that envisioned a new Africa.

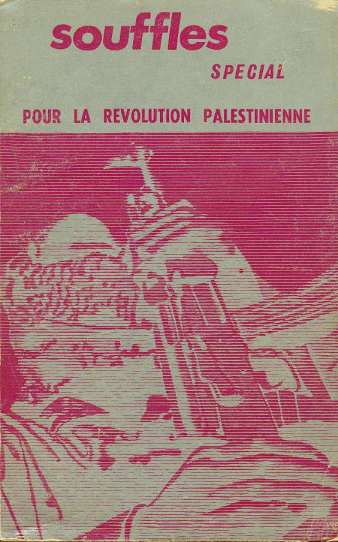

We meet Abdellatif Laâbi during the 1960s in Rabat, where he was creating the journalistic groundwork of the Maghreb Generation, namely a journal called Souffles, launched in 1966 and eventually banned by Morocco’s authorities, in 1972.

Born in Fes, but raised in Casablanca, Laâbi moved to Rabat where he continued living throughout the 1960s with his wife Jocelyne Laâbi. He emigrated to Paris in 1985, three years after his release from jail in 1982.

The first edition of Souffles was only about 30 pages long. Nonetheless, it created space for young Moroccans who did not agree with post-independence Morocco’s polity. Although based in Rabat, the journal would grow to become a large entity that would include writers from all over the world, mostly from Morocco, Algeria and the rest of Africa. [Olivia C. Harrison and Teresa Villa-Ignacio explore the influence of Souffles in their 2015 title, Souffles-Anfas, A Critical Anthology from the Moroccan Journal of Culture and Politics, Stanford University Press, 2015. ED]

Tolan-Szkilnik writes that Souffles editors’ “mission was the belief that decolonization was not finished, that continued vigilance was necessary to combat neo-colonialism and truly achieve political and cultural independence.” One of the inspirations they drew from was Frantz Fanon, whose ideas were analyzed, translated, and written about in the pages of the journal. Their work on Souffles resulted in an emerging discourse about the role of the intellectual and the artist in post-independent Africa. Through their writings they became the center of a worldwide conversation about neocolonialism, imperialism, and Pan-Africanism; Souffles was just one of many mediums in which the Maghreb Generation articulated their thoughts and visions, another being, of course, Jeune Afrique, founded in Tunis in 1960 and still going strong.

His opinions and writings in Souffles led to Laâbi’s imprisonment in 1972, by which time when the journal had become an important and widely recognized journal in both Arabic and French. In 1976, four years into his sentence, he wrote in a letter to his friend Mario de Andrade that “liberation is not limited to territory: it is the fight for men and women; it is the fight to throw, into the same trash can of history, colonialism, and racism, and it is based in the power of the people.”

(4e année, 3e trimestre 1969

directeur Abdellatif Laâbi).

Maghreb Noir is structured chronologically and geographically. It starts from the late 1950s in Rabat through the late 1960s in Algiers, and into the early 1970s in Tunis. The aim is to focus on different aspects of the various groups and how they collated their work. The author examines not only their journal, but the radio shows and films that depicted the lives and experiences of the Maghreb Generation. Interviews, which she conducted between 2018 and 2019, are the main sources from which the author draws her data.

When reading Maghreb Noir, it seems that the Maghreb Generation was not a typical group in its traditional meaning. They were scattered around the Maghreb and in the diaspora, working on different projects at different times. While there was a “core group,” which included Laâbi, there was no leader or spokesperson for the group. Treating the Maghreb Generation as a key to unlocking the region’s past also creates new approaches for a better understanding of its history as a whole. As the title suggests, Tolan-Szkilnik is most interested in the groups’ creative outcomes that form part of the legacy of this generation, which through a process of writing, discussion, and creation of materials emphasized the change they aimed to achieve within their societies.

The postcolonial future Tolan-Szkilnik has in mind is a concept larger than just a singular idea of the Maghreb Generation. It cannot be discussed in only one framework, but rather multi-layered frameworks imbedded in the postcolonial future. She writes that, “Morocco served as a transnational locus of resistance to colonialism and neocolonialism, and as a space to envision what African unity should look like.” While the book is a narrative about the Maghreb Generation, it is much more a story about the people inhabiting the generation, such as Abdellatif Laâbi who figures prominently.

Film was another medium in which the Maghreb Generation expressed their cultural, political and social endeavors to increase engagement in their works. The Journées Cinématographique de Carthage (JCC) in Tunisia became a space for members of the Maghreb Generation to politicize themselves and others through film. Their aim was to use art to push African people to action, and to “drive them to reclaim power from the postcolonial states.”

One chapter examines how Algiers and Tunis played a role in the evolution of the group and helped this generation grow. This evolution was part of the current movement that evolved during that time as the government started to crack down on the Maghreb Generation. While many were imprisoned, others, such as Jean Sénac who promoted the Maghreb Generation on his radio shows, were murdered and others were forced into exile. The chapters put each member of the Maghreb Generation at center stage, highlighting their work, where their views are discussed within the infrastructure of their time, and are narrated through the views of different artists.

Tolan-Szkilnik’s original title was Maghreb Generation, but the publisher’s final title, Maghreb Noir, is misleading, as it has nothing to do neither with blackness nor the noir fiction genre.

Maghreb Noir is at its best an attempt to bring into conversation the range of issues which were prominent in the films and writings of this generation. Each chapter is carefully grounded in the analysis of those mediums used by the Maghreb Generation; be they articles, films, or radio shows. Each chapter follows new artists and mediums the Maghreb Generation used to advance its cause. Tolan-Szkilnik’s command of her sources and analytical approach has provided readers with an insightful work that allows them to better understand the Maghreb and the nature of its cultural production between the 1950s and the 1970s.