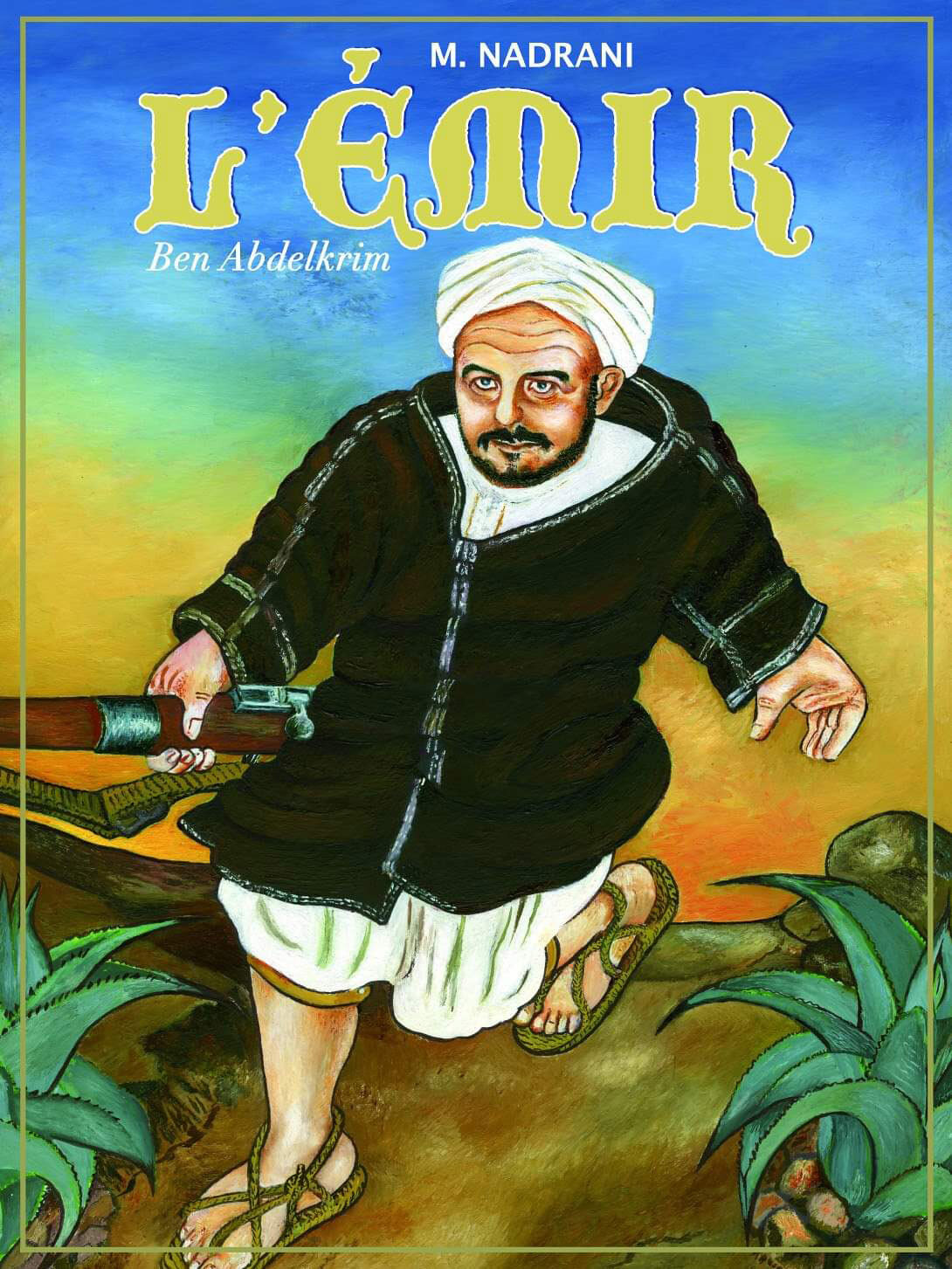

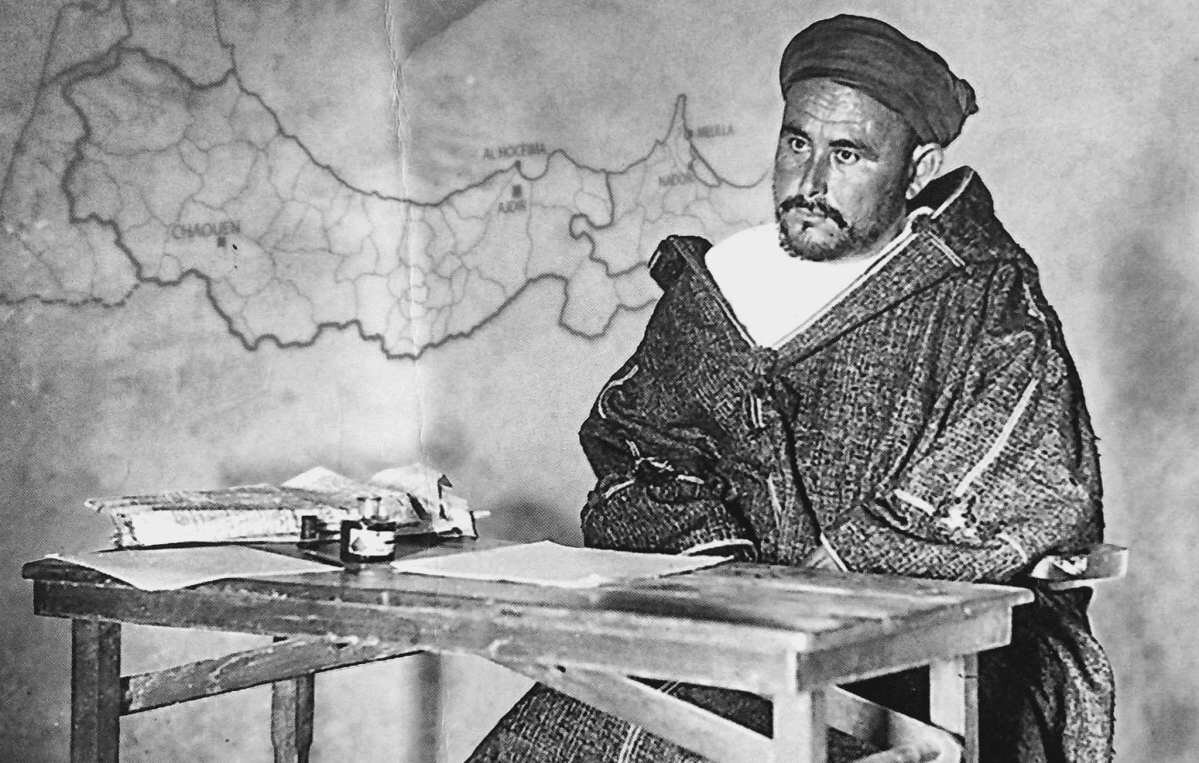

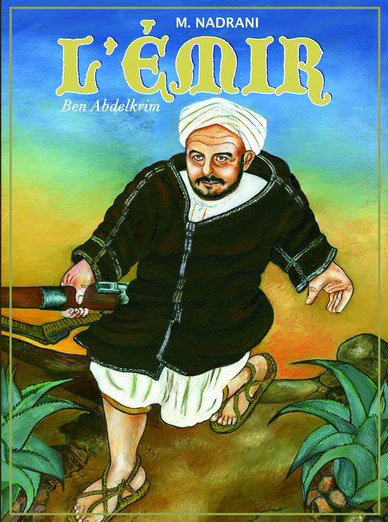

The legendary leader and Amazigh resistance fighter Mohamed Ben Abdelkrim El Khattabi (Abdelkrim).

Brahim El Guabli

Rarely has a person captured the imaginations of his Moroccan contemporaries and those of their descendants as Mohamed Ben Abdelkrim El Khattabi (Abdelkrim) has done. Likewise, no world-class hero and freedom fighter has been less celebrated, or even actively erased, in Moroccan post-colonial history as Abdelkrim. The gap between official erasure of Abdelkrim and his actual life in social and cultural memory, outside the purview of the state, point to an obdurate memory that refuses to dissipate and, instead, continues to reinvent itself.

Abdelkrim’s story is here to stay, and the best its opponents could do is turn their attention away from it. Because Abdelkrim, both the person and the myth, is immersed in ideals of liberation, independence, self-abnegation, transnational cooperation, pan-Arab struggles against foreign domination, and class consciousness — as a result, he stands for everything his opponents cannot. A liberator who was bilked out of his well-deserved right to history and memory, and a hero who could potentially overshadow those who did not fight the colonizers, wound up being in charge of independent Morocco. A president who established an independent republic in the Rif, Abdelkrim was a man who refused until the last day of his life to return to a country he considered still un-independent.[1] As a result, Abdelkrim has become an object of adulation, remembrance, and refusenik politics. Most recently, Abdelkrim’s memory has become a symbol of contestation and everyday resistance to neo-authoritarianism and social exclusion as is evidenced by the protests in the different ḥirākāt (social movements and protests) in the country.

The obduracy of Abdelkrim’s memory has taken a novel turn in Mohammed Nadrani’s graphic novel L’Émir Ben Abdelkrim (Emir Ben Abdelkrim, 2008). A former political prisoner, who was forcibly disappeared between April 12, 1976 and December 31, 1984, Nadrani learned how to draw while he was detained in the Kelâat M’Gouna secret prison, where he spent the last four years of his disappearance between 1980 and 1984.[2] His first comic, which is entitled Les Sarcophages du Complexe (The Sarcophagi of the Complex, 2005), is an autobiographical work in which he demonstrates “the real conditions of enforced disappearance” through images.[3] In Nadrani’s opinion, drawing was an act of revenge against the jailers who sought to disempower him, and art is “a weapon to fight against injustice and amnesia, and break silence and complicity.”[4] Nadrani and Abdelkrim share their experience of a state-mandated banishment, albeit in different ways, thus fostering a rich dialogue between their different experiences.

Abdelkrim hailed from a family of tribal chieftains and jurists educated in the Islamic tradition. Born and raised in Ajdir in the Aït Ourghail tribe in the Oriental Rif, Abdelkrim graduated from the Qarawiyyin mosque in Fes. Upon his return to Ajdir, he worked as a teacher, interpreter, and journalist in the Spanish-controlled enclave of Melilla. His life would be turned upside down by the Spanish invasion of the northern part of Morocco as part of the colonial arrangements that emanated from the conference of Algeciras in 1906. Abdelkrim’s shift from being a civil servant in the Spanish administration to becoming a military commander and president of a nascent republic in the Berber/Amazigh Rif region founded his ever -myth. Not only did he defeat the Spanish in the Battles of Annual on July 22, 1921, but he continued to resist them until both the French and the Spanish armies joined forces, under the command of the most important generals at the time, to force him to surrender in 1926.[5]

The collusion of the Moroccan authorities at the time with French and Spanish colonizers to end Abdelkrim’s resistance, and the reluctance of the post-independence state to request any inquiry into the use of chemical weapons, in what was believed to be the first chemical war in the world,[6] have since undergirded the feeling of historical injustice that befell Abdelkrim and his brand of resistant republicanism. Even today, Moroccans wonder why Mao Zedong, Che Guevara, Ho Chi Minh, and Gamal Abdel Nasser acknowledged Abdelkrim’s pioneering role as a leader of transnational liberation, whereas his perfection of guerilla tactics are met with oblivion in his own country. Dissimilarly to his global recognition as a master of guerilla war against imperialistic states, the official nonchalance, if not proud ignorance, displayed vis-à-vis his memory is indicative of an endeavor to forget that a regional resistance movement was able to carve out a republic in the north of the country.

Forgetting Abdelkrim means forgetting about the existence of his Republic of the Rif (1922-1926) and the fact that it once enjoyed its own sovereignty. The opposite is also true; commemorating Abdelkrim would certainly mean that one has to grapple with the paraphernalia and legacy of his short-lived republic. The Republic of the Rif, which evokes the Berber Bourghouata state in Tamsna (current Rabat), challenges cherished visions of national unity and bolsters arguments about the existence of a distinctly Amazigh political vision for statehood in North Africa.

The obduracy of Abdelkrim’s memory is, however, not merely attributable to his acts of resistance and the dynamic historical research that focuses on his life.[7] Abdelkrim is mythologized because he is prevented from occupying his rightful place in institutional memory. Therefore, cultural production, including film,[8] novel,[9] academic history, and social media commentaries are the loci in which Abdelkrim is remembered the most. It is even possible to argue that none has been as celebrated in film, novel, and history as he is. However, Nadrani’s graphic novel, L’Émir, is an efficient project, given the comic medium’s fast-traveling nature and its legibility for a large audience. In a society in which illiteracy is still prevalent, images, especially intensely political comics, have the power to endure in the receivers’ minds. Moreover, these images become objects of collective discussions, which expands their impact. Significantly, graphic novels and comics, which, in the witty words of Collin McKinney and David F. Richter, were “[o]nce considered a mere pastime of school boys and socially-awkward men […] have now wedged themselves firmly into both the mainstream literary landscape as well as serious literary scholarship.”[10] The reconfigured literary field in the 2000s has thrown the doors wide open for scholarship to grapple with the historical, familial, memorial, mnemonic, genocidal, and autobiographical dimensions of the comic inter-medial genre in which both writing and drawing coalesce to generate and convey meaning.[11]

Moroccan comic artists are not any different in using this medium to reflect on autobiographical and historical topics. Before Nadrani’s publication of L’Émir, Abdelaziz Mouride (d. 2013), another former political prisoner (1974-1984), had published On affame bien les rats (They really starve the rats! Don’t they?) about his own experience of political imprisonment after the trial of the Frontistes in 1977. As Susan Slyomovics has written, Mouride’s comic “chronicles the Marxist political prisoners’ emergence from years of enforced disappearance, his own in Derb Moulay Cherif in 1974-1976, to their reappearance at Casablanca Civil Prison in preparation for trials.”[12] Mouride’s unfinished comic version of Mohammed Choukri masterpiece’s al-Khubz al-ḥāfī (translated in English as For Bread Alone and in French as Le pain nu) was published posthumously in 2015. Although several former political prisoners learned how to draw in jail, Mouride and Nadrani are the pioneers of the Moroccan testimonial carceral comic genre, which chronicles and represents the daily life of prisoners within both the legal and the illegal detention system.

Nadrani’s approach to the memory of Abdelkrim is informed by a conviction that art has a role to play in history. First, Nadrani believes that comics are inherently biased towards just causes. Second, he is convinced that Abdelkrim’s true story has not been told. In one of his interviews he declared that, “the History of the hero of the Rif, which I hail from originally, has been hidden for political reasons for almost a century. For me, this part of the history of our country has been erased, falsified, and most of all disowned by the regime in place. They wanted to make this history disappear. It is up to us to revive this history in order to preserve the memory of our people.” [13]

As Nadrani’s words convey, comics, for him, are not just an artistic tool for aesthetic production. Comics are a reparative medium that allows the artist to get the historical record straight and put an end to the state of amnesia and historical injustice. Unsurprisingly, Nadrani sees his own story, as a descendant of the Rif, in Abdelkrim’s. The same political regime that erased Abdelkrim and condemned him to national oblivion was responsible for sending Nadrani to a nine-year enforced disappearance without a trial. The difference, however, is that Nadrani was able to reemerge from his disappearance and become an artist, whereas Abdelkrim’s remains are still in Egypt while the history he stands for is “under embargo.”[14]

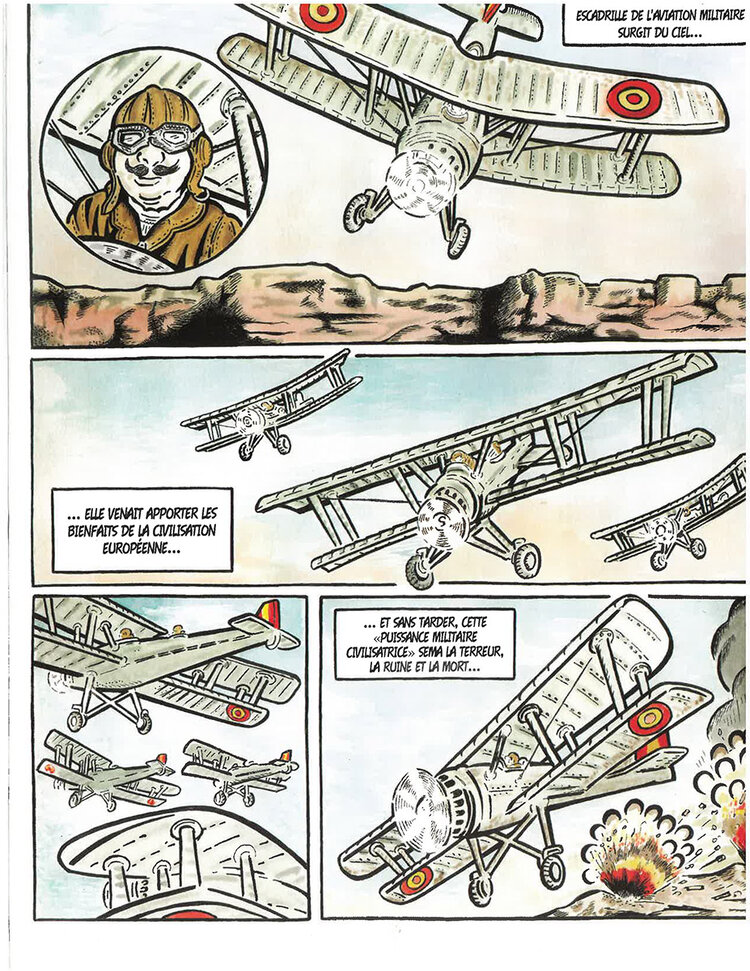

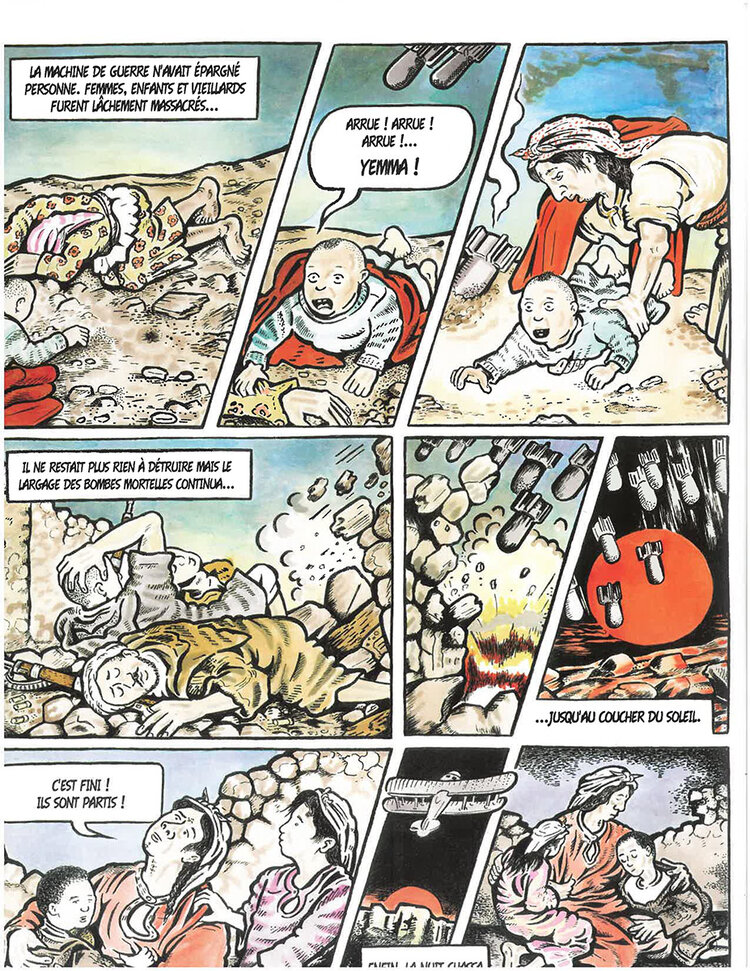

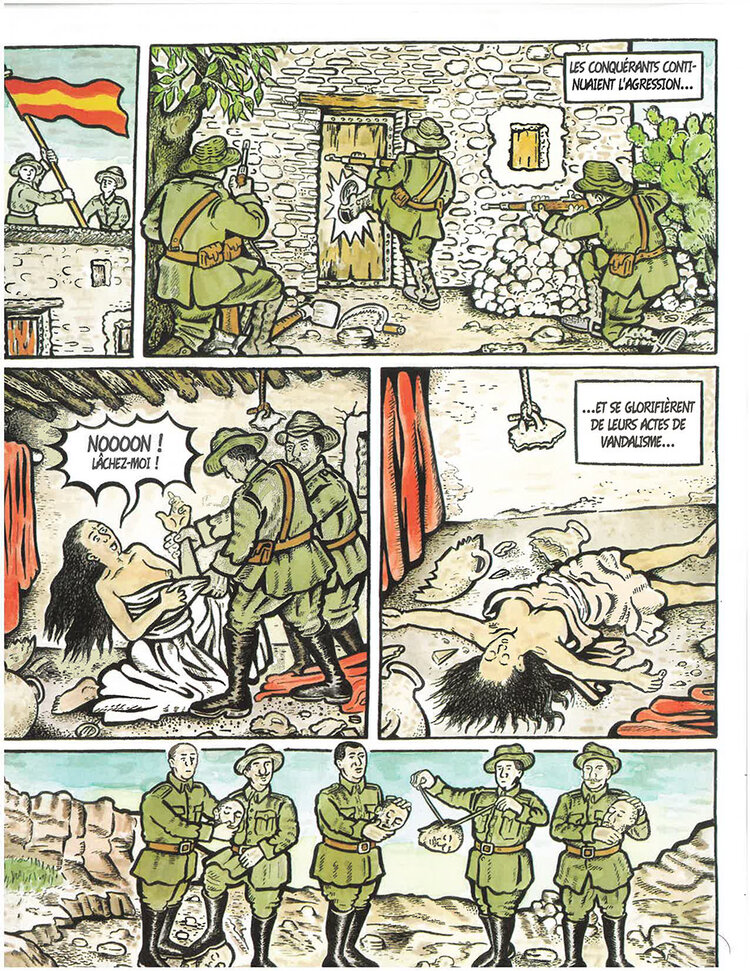

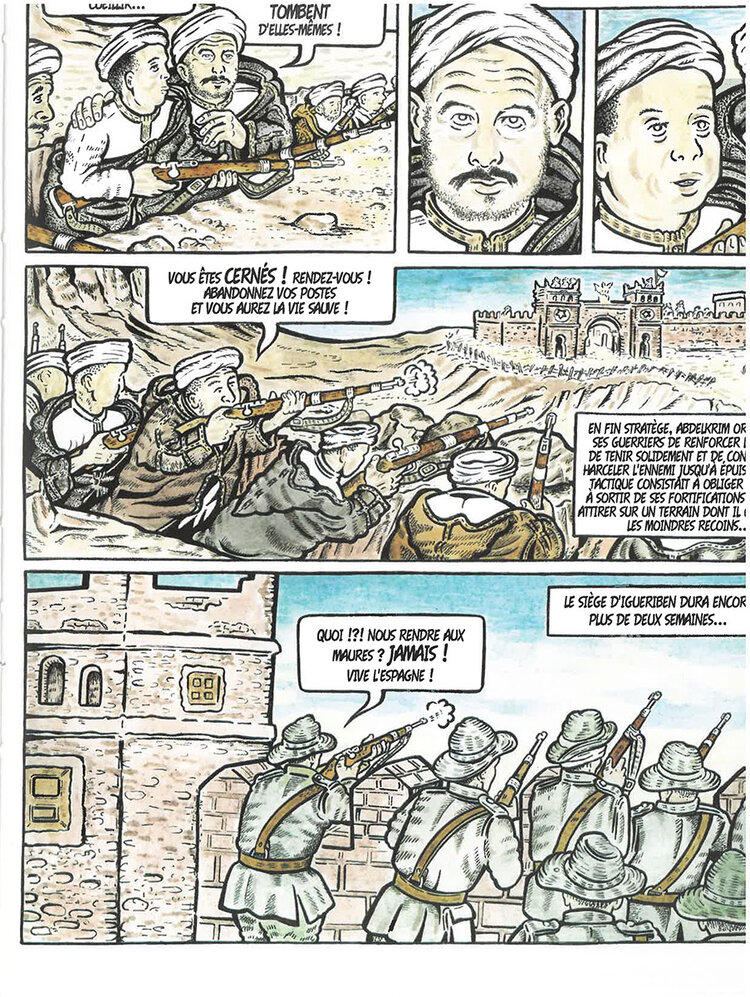

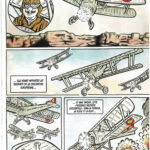

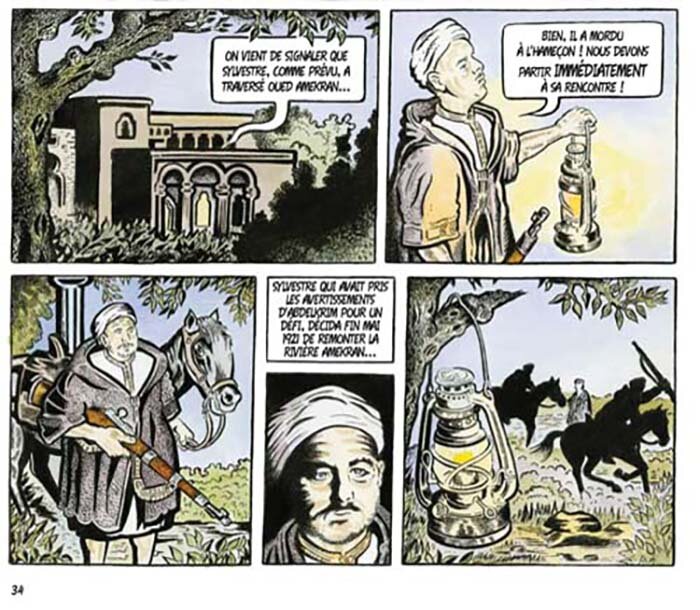

L’Émir can be divided into three moments that chronicle and reconstruct in artistic terms: 1) the brutal onslaught on the poor Riffian population by the Spanish army, 2) Abdelkrim’s organization of tribal resistance against the invaders after absorbing the shock of their surprise attacks, and 3) depictions of a series of victories by the Riffian resistance and the establishment of the Republic of the Riff in Ajdir. Throughout the comic, however, Nadrani’s distinctive style of drawing, which is characterized by an intentional focus on characters’ faces, is driven by a dialectical struggle between a dejected, Berber population and an imperialistic army. The text facilitates understanding the comic, especially in terms of dates and strategy, but the drawings speak for themselves and convey the significance of the history and the story Nadrani retells in L’Émir.

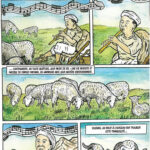

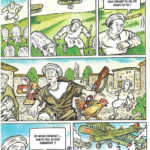

The first part of the comic contrasts a simple, almost idyllic, life before the mayhem caused by the advent of Spanish troops. The sheep are plump and the grass very green, symbolizing self-sufficiency. The sheepherder plays his flute, like in the old days, which indicates a carefree life. However, this simple and happy existence is then turned upside down by the Spanish bombs. The idyllic image is quickly replaced by gory scenes. Spanish modern artillery murders women, men, children, sheep, and chickens. As the Spanish occupy the territory, they also become central to this section of the story, eclipsing local populations. When Riffians appear, they are depicted as victims, being shot, raped, and assassinated. Riffian fighters’ heads are brandished by Spanish solders as trophies. The gruesome nature of the Spanish invasion seems to be designed to push populations away from their land by causing their displacement.

The second moment in the comic foregrounds Riffian resistance. Abdelkrim finds himself, almost providentially, at the helm of a resistance movement that momentarily put aside all disagreements between its tribal components to unify the fight against the Spanish enemy. The local, Amazigh motif is very present in this section of the comic. The men are depicted in short northern jellabas and skull cups (rẓẓā). Pure blood horses overshadow Spanish soldiers glad in green uniform and holding their then ultra-modern weapons. By focusing on the disparity between a well-clad, well-organized, and much more armed Spanish army and its Riffian opponents, who had nothing but their legitimate cause of liberation, Nadrani sets the stage for the binary opposition between the Spanish evil and the Riffian good.

The last moment in the comic shows the prevalence of the weak over the mighty. Riffian fighters defeat the Spanish army in the Battle of Annual. The enemy soldiers, who bombastically murdered and displaced local populations at the start of the comic, are now paying back for their crimes at the hands of a humane and ethical resistance. In an a very expressive scene Abdelkrim orders that the corpse of a dead officer be sent back home to his family without ransom. He was “a brave and loyal opponent,” says Abdelkrim. The reader finds out that the two men were colleagues in the Office of Indigenous Affairs in Melilla when Abdelkrim worked as a civil servant in Melilla. These moments of humanity in the battlefield create a contrast between Abdelkrim’s ethics and his adversaries’ contravention of the simple principles of war. The fighters return home triumphant, and the Rif will never be the same.

Foreshadowing the transformative nature of what just happened in the Battle of Annual, the last page of the comic starts with the image of an almond tree in full bloom. The commentary accompanying the image reads: “We are in 1922 in Ajdir. Spring will start soon and the first buds of almond trees are blooming…. A new era was going to start.”[15] The new era was nothing but the proclamation of Abdelkrim as President of the Republic of the Rif in Ajdir on February 1922. Ajdir has acquired a symbolic significance both as cradle of a resistance movement and a locus of an independent republic in the north of Morocco. Because of this history, Ajdir has rarely been spoken about. Even when King Mohammed VI announced the establishment of the Royal Institute for Amazigh Culture (IRCAM) in 2001, the announcement was made in the Ajdir located in the governorate of Khenifra. One Ajdir further envelops the other in amnesia. The flag of the new republic is reproduced three times, once alone, another on top of the maḥkama building, which served as a headquarters for the Riffian government, and finally in the background behind Abdelkrim during an official meeting in his office. The red flag, which has a white diamond in whose center are displayed a green crescent and pentagram, is a visual statement about the Republic of the Rif. From unifying the tribes to defeating the Spanish and establishing a local system of government, Riffians are shown as being studious and self-reliant. It is therefore, not surprising that the last scene of the comic presages a new era “of armed struggle for peoples’ enfranchisement.”[16]

As we know by now, Abdelkrim became an icon for transnational guerilla struggle against imperialism from Cuba to Vietnam. Despite his defeat in 1926 and his 21-year exile in La Réunion, his legend had already been established and his larger-than-life mythologized persona has taken pan-Arab, pan-Islamic, and pan-Third-World dimensions that surpassed any of the Moroccan postcolonial leaders.

This mythologization drives L’Émir. The comic reproduces knowledge that has been an object of oral transmission for eight decades. During one of his interviews, Nadrani declares that during his enforced disappearance, he and his colleagues were not allowed to read or write, but they strategized to fight against “erosion and forgetting.”[17] Abdelkrim’s story was one of the stories Nadrani registered within this action against amnesia. Abdelkrim’s arrested memory sustained Banou Hachim’s group resistance and informed Nadrani’s comic-based celebration of his legacy.

In addition to continuing the representation of Abdelkrim as a hero who is unjustly forgotten by the post-independence state, Nadrani’s comic recovers and recenters his story within the larger history of liberation in Morocco and beyond. His memory and silenced glory lend themselves to multiple forms of recuperation locally and globally. The proof is the mushrooming of Abdelkrim’s pictures, the recycling of his diatribes against colonialism in protest signs, and the brandishing of the flag of the Republic of the Rif during major protests. His memory is resignified and reinvented indefinitely to fight for social justice, democratization, and freedom. While all state means are put into action year-long to remind Moroccans of their three post-colonial monarchs, Abdelkrim has attained a phoenix-like status in Moroccan people’s collective memory. Abdelkrim’s is an obdurate memory — that is an action driven form of remembering that seeks to shape how the past is questioned and told.

For now, Abdelkrim has prevailed, even in comic form.

Endnotes

-

[1] ‘Abd al-Karīm Ghallāb . ‘Abd al-Karīm Ghallāb fī mudhakkirāt siyāsiyya wa-ṣiḥāfīya (Rabat: Maṭba‘at al-Ma‘ārīf al-Jadīda, 2010), 198.

-

[2] Mohammed Nadrani, “Mohammed Nadrani : le dessin ou la folie…,” Africulture.

-

[3] Nadrani, “ le dessin ou la folie.”

-

[4] Nadrani, “ le dessin ou la folie.”

-

[5] Zakya Daoud. Abdelkrim: Une épopée d’or et de sang (Paris : Séguier, 1999), 16.

-

[6] See Mustapha Mroun. Al-Tārīkh al-sirrī li-al-ḥarb al-kīmāwīyya diḍḍa minṭaqat al-rīf wa-jbāla (1921-1927) (Rabat: Dār al-Qalam, 2018)

-

[7] It is almost impossible to count the number of studies that have been done about him in Morocco and abroad.

-

[8] The script for “Albdelkrim y la epopeya del Rif” was written by Juan Goytisolo.

-

[9] Ahmed Beroho. Abdelkrim:Le lion du Rif (Tanger: Corail 2003)

-

[10] Collin McKinney and David F. Richter, eds. Spanish Graphic Narratives

-

Recent Developments in Sequential Art (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2020), 3.

-

[11] See, for example, Laurike in ’t Veld. The Representation of Genocide in Graphic Novels Considering the Role of Kitsch (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2019); Mihaela Precup. The Graphic Lives of Fathers: Memory, Representation, and Fatherhood in North American Autobiographical Comics (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2020); Maaheen Ahmed and Benoît Crucifix, eds. Comics Memory

-

Archives and Styles (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2018).

-

[12] Susan Slyomovics. The Performance of Human Rights in Morocco (Philadelphia: University Pennsylvania Press, 2005), 158.

-

[13] Nadrani, “ le dessin ou la folie.”

-

[14] Ali al-Idrissi. ‘Abd al-Karīm al-Khaṭṭābī: Al-tārīkh al-muḥāṣar (Casablanca: Maṭba‘at al-Ma‘ārif al-Jadīda, 2007)

-

[15] Mohammed Nadrani. L’Émir Ben Abdelkrim (Casablanca: Editions AL AYAM, 2008), 64.

-

[16] Nadrani, L’Émir, 64.

-

[17] Nadrani, “ le dessin ou la folie.”