As an enormous solar power plant springs up in the Moroccan desert near Ouarzazate, reconfiguring its visual and territorial makeup, there are worries it might overshadow the region’s rich cultural history.

Brahim El Guabli

I grew up in an arid region. Anyone raised in a desert environment knows that arid areas help you develop a strong sense of observation. You remember when a small plant appeared to change the look of your environment. You smell rain from far away and know that it’s coming your way. You learn not to trust dry rivers even in the dead of the summer because torrential rains may fall far away and can cause the flooding of rivers at any time.

You also learn to gaze at the sky and notice everything that is happening in your surroundings.

In some places, this may be a kind of science, but for desert environments it is part of life and being fully immersed in one’s ecosystem. When it rains, your heart bursts in happiness because you will soon see grass, flowers or other desert roots sprout from the ground. This acute awareness of the environment inhabits you, never to leave — even if you live thousands of miles away from home. I would add that absence from the homeland heightens this sense of observation. The desire, when you return home, to find and reconnect with familiar people and places sharpens it even more. It’s completely normal for the migrant to come back home and seek both the people and places they had left behind. Anthropologist Aomar Boum has captured many of the intricacies of this homecoming in his article “On Coming Home: The Elasticity of Migration.” The temporal space between each time you leave and the next time you come back is when entire demographic shifts take place in the community through death, marriages, and newborns. While this biological shift is entirely normal and smooth, any topographic change, on the other hand, is brutal to witness.

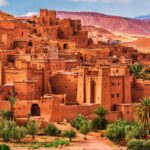

Although I was aware of this basic fact, I was not prepared to experience the brutality of the transformation I noticed when I returned to my village in southeast Morocco in December 2022. My annual visits had been suspended by the global pandemic for two and a half years, making the changes even more apparent. Not even the void left by the passing of my mother in 2017 surpassed the striking change that a two-hundred-meter-high solar energy tower (ttāqa) made to my familiar surroundings during my extended absence. My family and I used to be able to look at the Drâa Valley while eating our breakfast on the roof of our house. We could see the Atlas Mountains and the lush green fields and palm trees that form two parallel, green lines alongside the Drâa river bed. This was my favorite part of coming back home. I could sip Moroccan tea and eat lmsmn (Moroccan crepes) with cheese and jam while enjoying the extended time I spent scanning the beautiful landscape that stretched beyond what the eye can see. Even downtown Ouarzazate is visible from the roof, and its historic landmark — a concrete water tank — was until recently the highest building in the city. The rest of the environment is a coherently-integrated landscape in which reddish soil colors are interwoven with the green oases, which in turn, blend nicely with the sandy and pebbly bed of the oftentimes dry river. The many kasbahs that the blue Atlas mountains overlook from a distance, like ferocious guards ready to pounce on anyone who misbehaves in this unattainable land, have countless stories to tell about a history that has yet to be written.

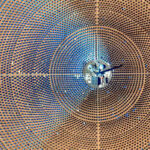

I first encountered the solar energy tower last December. I realized that the field of vision from the roof of my house had been changed forever. This very high tower with scorching hot projector-like mirrors at the top dominated the entirety of the area. When I first saw it, it reminded me of the high atomic towers that nuclear states build in deserts to drop their lethal creations. I knew it was not an atomic tower, but wherever I went and wherever I turned my face, I only saw one thing: an incandescent solar energy tower. It occupied my visual landscape, dominated the nature around us, and overshadowed the life that was, for sure, unfolding in its vicinity. Even when I did not want to look toward the tower, it looked at me and sent the reflections of its scorching hot flames in my direction, forcing me to stare at it longer and wonder about the impact of the burning fire at its pinnacle.

This phallic structure’s sudden appearance in my space spurred me to think more about its significance for the environment and the people who have now added a new word to their register. Ttāqa (both the energy and the tower) is now Amazighized, and the place is so self-referential that no one even bothers to define it. When you say ttāqa you mean the solar energy farm, the tower, and the energy it produces in the meantime. You also mean this monstrosity that has stolen visual attention from everything that Ouarzazate used to stand for.

Ttāqa in the local language refers to the local Noor-Ouarzazate solar project but also, albeit inadvertently, to a national project with transnational ramifications on renewable energies. As its “Value Chains” video posted on YouTube shows, the Moroccan Agency for Sustainable Energy (MASEN) was created in 2010 to harness all renewable energies across Morocco. In its brochure entitled “MASEN: An Inexhaustible Force of Development,” the agency seeks to produce %42 and then %52 of Morocco’s electricity from renewable sources. Seen from the Global North, this goal is both lofty and commendable.

It dovetails entirely with the global move towards renewable energies to mitigate the effects of global warming on planet earth. As a country that produces no gas, Morocco has pressing economic reasons to harvest sun and wind energy to achieve both energy security and self-sufficiency. However, there is always a gap between official discourse, which is abreast of international developments, and the way projects like ttāqa impact ordinary people. In a trenchant article entitled “Life in the Vicinity of Morocco’s Noor Solar Energy Project,” Moroccan sociologist, Zakia Salime, who conducted meticulous fieldwork in this area, has written that the lands on which the project is located “consist of 3,000 hectares slated to host the largest solar energy complex in the world.” Salime also draws attention to facts that the agency’s glossy literature has not addressed, adding that “8,000 villagers lost their access to collective pasture in 2010 due to this massive land acquisition.” Further complicating the issue of renewable energies, Salime highlights the long-term consequences of the discursive practices that are enmeshed in the agency’s integrated extractive approach. Salime’s compelling analysis opens up a breach in the temporality of solar energy and its devastating impact on the communities’ way of life and sense of self.

Ttāqa disrupted valued connections between people and territory, ushering in its commodification. In desert people’s value system, land has never been a commodity. It is inherited and passed down from generation to the next, and woe to the one who sells land! After all, land is mother earth and the connection to it should be one of nurturing and respect within a strict balance between need and desire rather than exploitation and extraction. Although he grew up thousands of kilometers away from southern Morocco, Ibrahim al-Koni, the Libyan Amazigh novelist, has written in his book Wațanī șahrā’ kubrā (My Homeland is Great Desert) that, “The bleeding of the earth, which is called oil, has managed to bring a curse on the people of the land because this liquid was really never petrol. In fact, it was the blood of our mother earth. Drilling it is a violation of the belly of this mother and a defiling of its sacred soul.” However, the advent of extractive entities has upended these value systems, creating, along the way, the conditions for additional precarity and dispossession in areas formerly spared the encroachment of extractive capitalism. Because land was not commodified, communal land ownership practices ensured that everyone had a parcel of land to build a home, and homelessness is unheard of. Until recently, renting a house was not even a thing in the region. If you owned an empty house that you no longer needed, you lent it for free to a property-less family until they could afford to have their own house built.

There is a saying that one can hide hunger but they cannot hide homelessness. This proverb emphasizes the importance of having a place to live. The communal land that was distributed amongst community members, despite all the problems that stemmed from intra-community favoritism and internal power dynamics, created a land-based safety network for everyone. Land and water have always been essential for sustained existence in any desert community. Starting from 2000, however, many village communities lost their ancestral lands to investment schemes that dispossessed people in the southeast. The process started even before the 2000s in places that had valuable land. This land governance appeared in the early 1990s in different places, where state agents kept simple intra-community conflicts unresolved within land-rich villages in order to sustain the factors of inter-communal conflict irresolution to, as a result, expropriate their valuable lands. Only recently did it become clear that the irresolution of technical disagreements over land in land-rich communities was a strategy to facilitate the confiscation of their ancestral lands, which are now parceled out to rich investors who have turned them into lucrative projects. As a result, the rich are getting richer whereas the descendants of those who once owned the land are doomed to buy it from the descendants of these land grabbers in the future.

Beyond the questions of land and dispossession of local communities, ttāqa’s exuberant presence colonizes Ouarzazate’s identity. Whether you fly into or out of Ouarzazate, the solar power tower is the first thing you see from the airport. During the day, this panopticon structure, which my wife likened to the “Eye of Sauron,” acts like an omnipresent, divine eye that has a 360-degree field of vision. Whichever direction I went, the tower was there to remind me that the space I had known my entire life is no longer what it used to be. The sea of solar panels, which exquisite Moroccan engineering skills combined with cutting-edge European technology and multinational adventure capitalist investors’ money built, swallowed a sprawling 8,000 acres of communal land. What once served as a pasture terrain and potential land for farming and construction is now occupied by a colossal and far-reaching technostructure that transforms sun rays into electricity. The imposing nature of the structure inspires awe. Seen within the semi-desertic environment, ttāqa has a sublime presence that dazzles the eyes of those who have not encountered technology of this scale in their immediate environment.

Ttāqa tower is not different from the various desert-focused projects in different parts of the world. From California, where the US, Department of Land Management has developed a Desert Renewable Energy Conservation Plan to generate electricity to western Saudi Arabia, where the state is building the Neom desert city, these different approaches have a longer history that is embedded in the understanding of deserts as spaces for pioneerism, testing and experimentation.

Saharanism, the imaginary, which I argue, underlies these endeavors, has a long history of perceiving deserts not only as empty and extractable but also as safe spaces where what happens in deserts stays in deserts. The desert is mistakenly seen as a sealed off world where things can be hidden. As I show in my forthcoming book Desert Imaginations, images of virginity and novelty were projected on deserts to accommodate the myriad extractive activities that took place in them. MASEN’s aforementioned promotional video states that “[b]efore the intervention of MASEN and the National Office for Electricity, these barren lands were devoid of any activity. The wind blew on the mountains without turning any turbines and the water flew in the rivers without being stored in dams.” These statements are part of a long lineage of colonialist thinking about deserts spaces as exploitable and extraction-friendly spaces, revealing, in the meantime, the Saharanism’s pervasive nature even in places where we might expect awareness of its dangers.

The visitor who only sees the universalized “Eye of Sauron,” which waylays them in every direction, may leave Ouarzazate thinking that it is only a place for films and solar energy. The tower’s overbearing presence and its sublime presence foster amnesia.

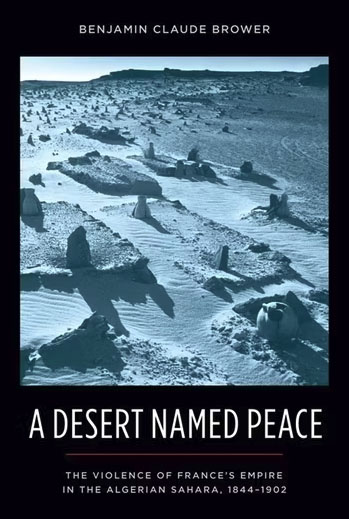

Images of desert virginity and unusedness actively wipe out multi-secular histories of pastoralism and nomadism on the land. The shepherds who used to cross these acres with their sheep do not count in the age of solar energy, which mobilizes advanced technologies to harvest the sun rays. The life style Saharans have always taken for granted is now declared useless by solar energy gurus who rewrite history based on a land’s contribution to myriad forms of extraction. This same line of transforming the desert underlies the statement of MASEN’s head of the Department of Technical Design at MASEN when she takes pride in “transforming a bare, sterile, and unusable land into something green, flamboyant that will enlighten the lives of many households.” The insistence on the land’s barrenness and sterility is not a new trope in deserts spaces. Deserts have always been seen as tabula rasas where inventors of all persuasions could leave their imprint by testing the next thing that would change the course of human history. After all, as historian Benjamin Brower argues compellingly in his book A Desert Named Peace, the desert has been associated with desires, but also with various forms of violence meted to the people, ideas, property, and the environment.

As ttāqa’s era reconfigures the visual and territorial makeup of my hometown, there is a real danger that solar modernity will overshadow the area’s rich cultural histories. Our world will definitely be a better place with less gas emissions. The more humans are able to decrease the greenhouse effect’s impact on the environment, the better for our planet earth. However, we also have to take heed of the fact that producing cleaner energy takes a toll on communities whose lands are seized to generate this exportable energy. Each time I looked towards the ttāqa or rather, more accurately, each time it looked at me, I could not but worry about the myriad local histories that will be relegated to oblivion. Ouarzazate has already experienced several erasures as a global open-air cinematic studio for Hollywood movies. Pursuing a Saharanism-infused vision, the desert landscape has stood in in multiple movies for ancient Arabia, war-torn Yemen, biblical Palestine, and World War II Sahara, among others. Its identity as a historical space that once linked Morocco to the Sahara and the role it occupied in colonial strategies have become arcane knowledge glossed over by more powerful images of international cinema.

The ttāqa adds more complexity to this situation, the pasture lands, which were used for generations, have already been cast as virgin or sterile lands in the discourse of energy technocrats. History-rich villages, which witnessed tremendous historical events, are already tucked away in the mountains, where centuries-old kasbahs are falling to ruins, but solar energy technomodernity will further eclipse them. Who will remember El Glaoui and his lengthy rule in the region? Who will remember that the dam that feeds the enormous installation with water used to house political prisoners in the 1970s? Who will remember that General Madbouh, the first governor of Ouarzazate after independence, was the mastermind of the first coup against King Hassan II? This is not to say that the solar energy agency is actively erasing history, but rather that there is a risk that all people will remember about the place is the cinema studios and the ttāqa’s technostrucure. The visitor who only sees the universalized “Eye of Sauron,” which waylays them in every direction, may leave Ouarzazate thinking that it is only a place for films and solar energy. The tower’s overbearing presence and its sublime presence foster amnesia. Even as local sites of historical significance wane as a result of negligence, ttāqa glows every day under the watchful eyes of an army of dedicated technicians and engineers. The imposing nature of the installation discombobulates the mind and prevents one from asking questions about the land and its ownership.

At sunset, ttāqa disappears. Its incandescent eyes stop glowing even as the energy it stored during the day continues to generate electricity for another seven hours after the sun sets. Because of its omnipresence during the day, I could not but look for the tower at night only to be reminded that it is like an elusive phoenix; it appears during the day only to disappear at night. This reminded me of my childhood in my 1980s electricity-less village. We enthusiastically waited for sunset in order to form a circle around the fire or lamba (the lamp) to hear stories from the mouths of our parents. Now that the sunset had weaned off the tower, and its light has gone out for the night, I wondered what stories the elders were telling their children, if any. I wondered if somewhere in the villages closer to the ttāqa a grandfather or a grandmother starts a story to their grandchildren with the mantra “once before ttāqa, we had access to our land….” There was no way for me to know, but I am all hope that the story of the land is passed down to the next generations.

The only thing I knew for certain was that ttāqa followed me into the plane the next morning, and it was the most visible part of the city as my flight took off to Casablanca.

Professor Brahim El Guabli’s indigenous eye is a preserve of the culture of Earth’s desert lands.

Haunting, powerful, informative, Brahim. Tying in your work on Saharanism to the technological land grab gives this piece even more historical and global significance. I appreciate that you problematize how solar energy, a seemingly all-positive, can be part of the same logic of extractavist capitalism and colonialism. Very moving to read of your returns to the village and how deeply the land resides in you, and how fraught that ancestral memory becomes.