On the 60th anniversary of Algeria’s independence, this essay seeks to answer why Algerian-Franco relations have always been strained, and why they are likely to remain so.

Fouad Mami

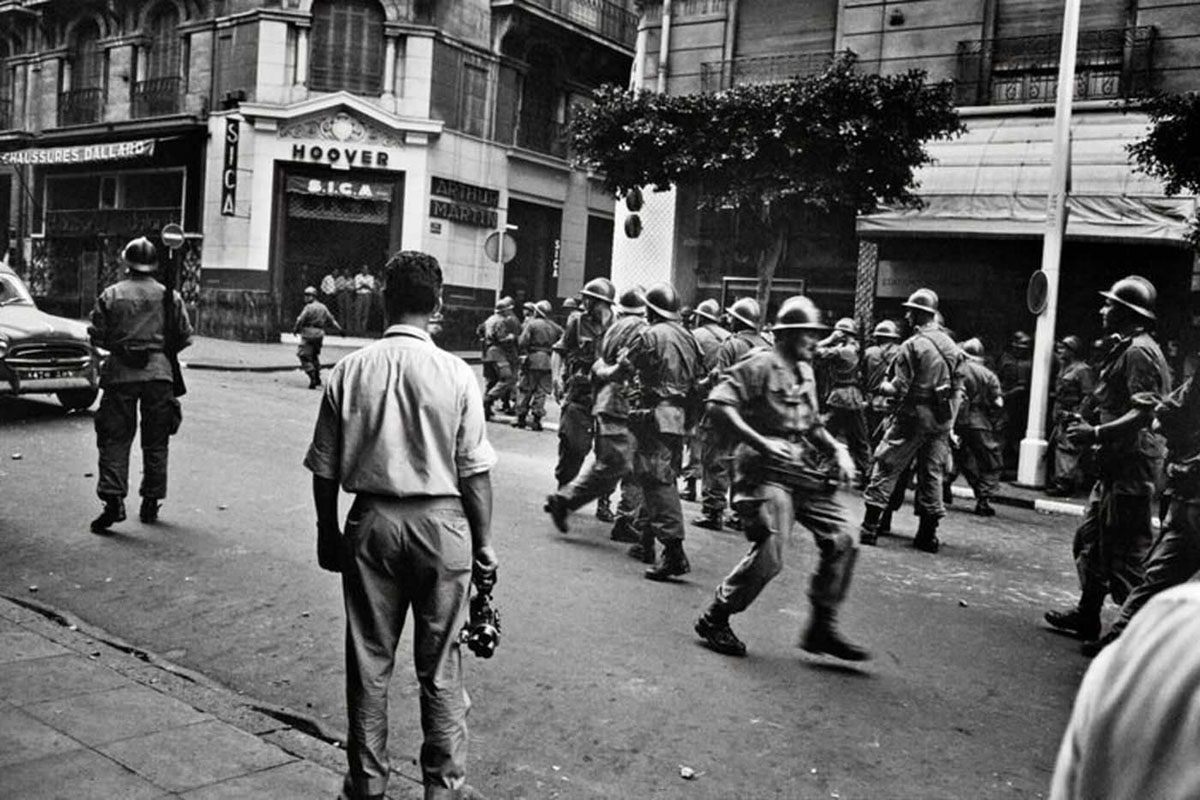

Relations between Algiers and Paris remain tense despite six decades of diplomacy. Three interrelated reasons include the fact that the European colonists, after living in Algeria for four generations, lost everything with the country’s attainment of independence in 1962, an event that marked the collapse of their project of l’Algérie française. Not only did they lose everything, but they moved, en masse, to France and became an additional burden to a country still reconstructing after WWII. Second, due to the circumstances of Algeria’s decolonization, the French establishment, in which the media is a key player, remains exceptionally sensitive when other countries’ companies, such as those of the US and China, gain important shares in the lucrative Algerian market. And third, following its victory in WWII, not a single power on earth dared to say no to the US, which was pushing for decolonization. US policymakers wanted decolonization not because they loved Indians, Algerians, or Kenyans, but because only decolonization guaranteed US companies an advantage over French, British, or Dutch companies.

Albert Camus (1913-1960), a Nobel Laureate for literature, was born and raised in colonial Algeria. He is largely considered in independent Algeria as the spokesperson of white settlers, perhaps even the pride of a social class better known as les pieds noirs, descendants of white settlers or colonists (French but also other Europeans) who settled after the conquest of Algeria in 1830. They acquired fertile land at a fraction of the cost following the decimation of native tribes and the ruinous policies that led to the dispossession of the remaining inhabitants from their communal lands. The early colonists are branded as pioneers. They worked the land and rendered it extremely productive.

During the 1930s, the colonists entertained that if America is proud of California, then France is proud of Orléansville, today’s the governorate of Chelf and the surrounding region. True, these colonists were industrious but they were notoriously known for exploiting dispossessed Algerians. Russian convicts, who lived through the reign of the last Tsar and were serving prison terms around the 1910s in Bône, were shocked to find that the colonists treated Algerians worse than sheep.[1] With the end of military rule in the 1880s, colonists (not Metropolitan France) were responsible — through exclusionary practices — for literally sending Algerians behind the sun. Understandably, by the time the Algerian revolution broke out in November 1954, everything the colonists fought and stood for was at stake, as most of them at that point had been four generations in the colony.

To give non-Algerian and non-French readers a taste of la déchirure, or the disheartening misfortune of these colonists brought about by Algeria’s independence in 1962, consider this analogy. In South Africa, Nelson Mandela was awarded the Nobel Prize for Peace simply because he did not repeat the Algerian tragedy. Mandela kept intact the economic privileges white colonists had enjoyed during apartheid. He did not start a policy or propagate a process leading to their eventual eviction or dispossession. White liberals and their media adore Mandela for not doing what the FLN is thought to have done with white colonists a mere three decades earlier.

Here is where Camus’s conciliatory discourse during Algeria’s war of independence becomes relevant. He is famous/infamous for adopting his mother’s point of view at the expense of justice.[2] Because I hail from the very people sent behind the sun by Camus’ ancestors, I find any engagement with that “justice-versus-mother” discussion a dead horse. How so? The terrorism Camus refers to in the quote was not terrorism; these were some people’s deliberate actions of emancipation, so that they might re-enter history after more than a century of denial. Hence the euphoric reactions captured through Algerian songs and other cultural artifacts, such as: “يا محمدمبروك عليك الجزائر رجعت ليك”. [3]

While a student at Algiers University during the 1990s, I took part in several discussions regarding whether or not Camus was a misunderstood universalist or a bloody racist. I can say now that lyricism, of the sort he and others employ, does not even begin to resolve historical conflicts. Reading Camus may make one more sensible, and more sensitive to certain complexities, but at the end of the day poetic formulations of his and his ilk (Mouloud Feraoun, for one) do not advance the cause of emancipation one jot. Lyrics and poeticism are what the French brilliantly capture through the expression des masturbations a l’infini.

Advancing this position, I am aware, comes at the risk of effecting a major offense to liberal sensibilities since Camus has been the darling of liberals.

Similarly, it is worth recalling that with the conclusion of the Evian Agreements, colonists became personas non grata, undesired in a country they called theirs. A large number of them knew no other country to call theirs but Algeria. Today Algerians perfectly understand and even sympathize with their misfortune. Strangely, the Evian Agreements guaranteed the colonists’ right to stay. But it is they who sealed their fate in calling for and acting to keep Algeria French. Had they stayed, I and my kind (practically sons of impoverished peasants) would never have had the chance to make it beyond primary school. We would have been condemned, like our forefathers, to subservient positions. It is no exaggeration that by literally enslaving Algerians, not a small number of colonists lived like royalty. Hence the context for nostalgia and the rumination over a French Algeria in contemporary France. Knowing that originally these colonists hailed from peasant and working-class backgrounds, it is understandable that they bemoan what they lost. And Camus is an icon for everything they aspire to, the entrepreneurial self-made model.

Now, concerning how independent Algeria has fared, volumes can be written about political dysfunction and corruption. But for the sake of fairness, we must admit that today every Algerian is entitled to free education, health insurance, dignified lodgings, etc. Only those blinded by hatred of Algeria can deny these material gains.

Once independence was secured, the struggle shifted and became, first and foremost, one of class. Yet the predominant nationalist discourse prevailing after independence only seeks to asphyxiate the class war. Through several slogans, Le hirak (peaceful uprising) of February 2019 articulated that class dimension. Still, the triumphant narrative tried and succeeded in portraying it as no more than exasperation with Bouteflika and his cronies. Yet le hirak is much more than that. It is an incendiary insurrection against the entire postcolonial order, not just its Bouteflika iteration.

Who stood against the progressive policies of Metropolitan France? None other than the colonists. In 1962, these colonists got what they, as a class, historically deserved. Outlining this does not make Algerians blind to the fact that several colonists openly supported decolonization. The violence during the revolution settled scores; that violence, as Frantz Fanon (1925-1961) brilliantly puts it in The Wretched of the Earth, had purifying effects in the sense that it enabled the human being in the colonized to emerge. Recall that with Fanon as well as with the Franco-Tunisian scholar Albert Memmi (1920-2020), the colonized is a strange combination of deformities. The colonized had to kill the colonized within him or her to join the realm of the human. Violence, of the sort that took place during the Algerian revolutionary war (1954-1962) was, for Fanon, an unfortunate but necessary maneuver to allow the man in the colonized to be born.

Regarding present Franco-Algerian relations, they too cannot be stripped of context. Not all the criticisms one reads in the French media are accurate or innocent or not propaganda. It is not news that there exists bias in reporting corruption in Algeria. Many observers recall that the first people who brought to public attention the overpricing of the 1,200 km highway in 2006 were the French media. Why? French companies, like American, Japanese, and South Korean ones, made their bids. But the project was contracted by three large and state-owned Chinese construction companies and a Japanese one. Why? Simply because Algerian bureaucrats did their job. They handed the project to the lowest bidder. But the initial fund meant to cover the construction was not enough, so the contracted companies asked for what is legally theirs. The highway is not Germany’s Autobahn, but its cost is reasonable. And the delivered infrastructure is not bad, as is often reported. Similarly, the French media become furious when the authorities handed the contract for building the largest dam in the Maghreb, that of Beni Haroun in 2001, to the Chinese. The contract was mouthwatering and soon the usual media fault-finding started. Bouteflika’s reign has been extremely problematic, but there remains a duty to be fair.

Big contracts for building key infrastructure, such as those outlined above, are among a handful of examples of why tensions have always governed the relationship between independent Algeria and France. The cultural explanation, as proposed by the Algerian establishment, often aims to justify, and rarely to explain. The tension has deep roots in material history and the meaning of primitive accumulation. It is the tendential fall in the rate of profits (as specified by Karl Marx in volume three of Capital) that obliges French companies to compete against more vibrant American companies for shares in Algerian markets, which in turn creates tension.. The selectivity in discussion of corruption seeks to cover that public officials’ mishandling of assets cannot significantly account for the contradictions that underlie globalization. The latter has no preference for one national capital — a situation that generates tensions among competing capitalisms marking globalization. To illustrate, Algeria’s decision to nationalize its energy sector in February 1971 gave leverage to American companies at the expense of French ones.

If one aims to address the subterranean forces that shape Franco-Algerian relations, one should consider the thesis proposed by Gregory D. Cleva in John F. Kennedy’s 1957 Algeria Speech: The Politics of Anticolonialism in the Cold War Era (2022). The gist of Cleva’s book is that in the wake of that speech, a pattern was set for the relationship not only between the US and Algeria or the US and France but between the Algerian and French establishments. Leaving the ephemeral (that which the French media deems newsworthy) and embracing the essential, JFK’s 1957 Algeria Speech is the way to go. Otherwise, neither staunch Algerian nationalists nor largely nostalgic French journalists and academics highlight, let alone address, the intricate web of connections at play.

For many ordinary Algerians, the FLN eventually won because it forced de Gaulle to accept negotiations. Under the carpet, however, lies the fact that by the time JFK made his speech, the Algerian revolution had been militarily defeated. The French generals’ strategy to defeat the insurrection had borne fruit. And still, the revolution, in the final analysis, got what it wanted! Strange, isn’t it? This is because other forces were working against French policymakers and in favor of the FLN, though not necessarily for the sake of the Algerian people. We read in Cleva’s account that American consuls general in Algiers serving from 1942 to the late 1950s played key roles by reporting the pitfalls of French colonial policies. As a member of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations and thus a likely candidate for the presidency, JFK formalized what the American establishment, up to that point, had always wanted.

The U.S. did not emerge from WWII victorious just like that. The world still remembers how President Donald Trump in November 2018 reacted to French President Emmanuel Macron’s allusion to the need to create an independent European army, a framework outside NATO. Trump angrily retorts: “Without the U.S. help in two world wars, today’s Parisians would be speaking German.” The point here is that while the French generals overwhelmingly succeeded in suppressing the insurrection in Algeria, French politicians could not capitalize on that success because Washington wanted otherwise. The US pushed a policy of decolonization and not even Britain was immune. India, the jewel of its empire, won its independence!

With his return to power in 1958, le général (de Gaulle) tried his best to secure Algeria as French but eventually realized that his maneuvers would amount to little more than showmanship. US geostrategic interests wanted an end to colonization, lest upheavals and insurrections in the colonies break the fragile new order. Decolonization as a policy was meant to contain the colonized, regardless of the fact that, on the surface, it gave them better terms (though not the best) to negotiate their future emancipation. For Indians as much as for Algerians or Kenyans, what happened on the battlefield was important, but independence was largely decided elsewhere.

If literature is but another means of changing the world, not just an instantiation of the bourgeois hunt for the beautiful, then it is Yacine’s synthesis of Algerians’ radical consciousness that illuminates the way for contemporary Algerians to achieve a greater degree of emancipation.

This leaves us with an accurate picture of how the French establishment views Algeria today. France sees Algeria as a concubine that simply decided to exchange partners and go to bed with Washington. All other approximations to those relations are meant to justify, never to explain what the French establishment to this day cannot overcome what it considers as the impossible loss! But it is precisely here where Algerians prefer to overlook the American role and attribute victory exclusively to their forefathers’ sacrifices.

Speaking of the post-independent nationalist narrative brings us full circle to why discussions of Camus’s universalism or chauvinism are sterile. They are so because they remain outside space and time. They are meant to cover for the type of reasoning that seeks to eternalize the present unjust order rooted in exploitation and which decolonization has sought to restructure into a higher but still unjust order. Differently put, Camus’s narrative of the nationalists and his mother is, quite simply, false.

Speaking about the exact stakes of European colonists leads us to learn about subaltern Algerians’ exact sakes in their country. Anyone serious about understanding disenfranchised Algerians’ exact stakes should read Kateb Yacine (1929-1989) and his 1956 novel, Nedjma. On the very first page of Nedjma, one will see how Camus was out of touch with reality. That first page saves readers from that fogginess and makes them fully register the class struggle. One will realize how acute Algerians’ living conditions were and how the consciousness of the necessity of bloodshed manifested itself — not because Algerians liked it, but because they were squeezed out of options. On that first page, Yacine captures Algerians’ logos, the reflective consciousness that looks at the abyss but is not afraid to tease it out and distill the sensible course of action. In considering social class as a vector for analysis, it becomes self-evident that Camus does not even begin to compare with Yacine. If literature is but another means of changing the world, not just an instantiation of the bourgeois hunt for the beautiful, then it is Yacine’s synthesis of Algerians’ radical consciousness that illuminates the way for contemporary Algerians to achieve a greater degree of emancipation.

Notes

[1] Owen White, 2021. The Blood of the Colony: Wine and the Rise and Fall of French Algeria. Harvard University Press.

[2] “I have always denounced terrorism. I must also denounce terrorism which is exercised blindly, in the streets of Algiers for example, and which someday could strike my mother or my family. I believe in justice, but I shall defend my mother above justice.” Herbert R. Lottman, Camus, A Biography (1979)

[3] Literally, “congratulations to you Mohammad; Algeria is back to you again!” or consider this largely forgotten one now “Fransa mellat” by Cheikh Bouregaa.