One of Algeria’s most eminent international artists has created another beautiful garden, this time to honor the anonymous migrants or harragas who have fallen at sea.

Rose Issa

Visual artist Rachid Koraïchi was born in the Aurès region of Algeria. He has set up studios in various countries around the world, depending on what projects he is working on. His search for the best artisan “magicians” follows his creative path. From the outset he has built a deep, friendly complicity with the great poets and writers of the past century. He is also inspired by ancient texts. This versatile artist, linked to the Koraïchi family of the Prophet Muhammad, is deeply spiritual. His most recent project is Jardin d’Afrique (Garden of Africa), a cemetery for irregular migrants in the coastal town of Zarzis, southern Tunisia.

Les descendants d’Adam sont membres d’un seul corps, car ils furent crées d’une seule et même essence. Que le destin un jour fasse souffrir un membre, les autres membres aussi en seront affligés. Su tu ne souffres pas de la souffrance des autres, tu ne mérites pas d’être appelé humain. (The descendants of Adam are members of one body, for they were created of one essence. If fate one day causes one member to suffer, the other members will also suffer. If you do not suffer from the suffering of others, you do not deserve to be called human.)

—Rachid Koraïchi

ROSE ISSA: Rachid, how did this project originate?

RACHID KORAÏCHI: My daughter Aïcha, vice-chair of Action Against Hunger in London, alerted me to the existence of a public landfill site where the bodies of migrants washed up by the sea were deposited at Zarzis. For me, that seemed so unlikely that I wanted to go there with her. I contacted Mongi Slim of the Tunisian Red Crescent (humanitarian organization affiliated with the Red Cross), who took us to the site. I was so shocked by what I saw, I decided to purchase some land to create a decent burial site.

As my daughter is a Tunisian citizen, we were able to acquire a plot for the future Garden of Africa. The next day, in the presence of Mongi Slim and his contractor, I sketched out the entire project down to the last detail, ignoring all the administrative, legal and judicial red tape required for a burial ground. This is the world’s first private cemetery. It is only for the bodies of migrants or foreigners. In total there are eight hundred tombs, most of which are occupied.

ROSE ISSA: How did you design your project?

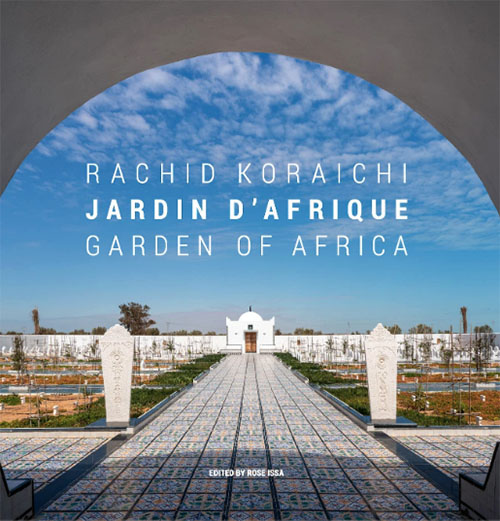

RACHID KORAÏCHI: I called this site Garden of Africa to erase the image of it having been a landfill site. For all of those bodies I had a vision of the Gardens of Paradise. I wanted this memorial to be totally non-denominational, with no discrimination according to religion. All the bodies are orientated towards the sunrise, even if it is the direction of the Kaaba. The layout incorporates a prayer room open to all faiths. Above the dome are three green ceramic balls, symbolizing Judaism, Christianity and Islam. The whole is surmounted by a crescent open to the sky like a cup receiving abundance from the heavens. This project is an offering to the deceased, to their families, to their tribes.

I wanted the presence of large steles commemorating two kings, father and son of the Koraïchi family who reigned in the 12th century at Daghestan in the Caucasus. These steles stand as symbols of protection that accompany the dead. This links to the other ancestors who are buried in the Koraïchi cemetery, against the perimeter wall of the great mosque of Kairouan. These are the same people who founded this city in the 7th century and who bequeathed us the famous Blue Qur’an.

The door to the prayer room, purchased from an antique dealer, dates from the 17th century. At the entrance, the bodies pass through the large front door, which is the color of light and sun. Ahead stretches a long corridor of ceramic tiles, hand-made in the style of 17th-century Tunis palaces. The building has a welcoming atmosphere filled with dignity, respect and love. The tombs are white with an inlaid ceramic bowl of green and yellow on top, the green symbolizing abundance and the yellow, light. This bowl fills only with rainwater, which fertilizes the soil, the invisible journey from heaven to earth. It serves to water the birds that are born and then fly away to meet the angels. On this other invisible journey to heaven, the bird symbolically accompanies the souls of the deceased.

The choice of plants comes from sacred texts describing Paradise. From the outside, a 130-year-old olive tree, a symbol of peace, opens onto a view of the prayer hall in the distance. On either side of the entrance, you can see five olive trees, representing the Five Pillars of Islam: Shahada (faith), Salat (prayer), Zakat (almsgiving), Sawm (fasting) and Hajj (pilgrimage to Mecca). Perpendicularly, along the surrounding walls, twelve large vines facing each other represent the twelve apostles around Christ. At the four corners, I brought in four great big desert palm trees. They represent protection: in the heat of the Sahara, they protect fruit trees and market gardens from the intensity of the sun and stop them drying out. Sufi masters compare them to human beings because they live to be 90 years of age. If you cut them down, they die as if decapitated. Everything in the palm tree is useful.

On each side of the central aisle, you first see a row of bitter orange trees: a sign both of the bitterness of death and the sweetness of the fruit, and of the perfume of orange blossom water, known as maa zhar (the water that brings luck). The next row is planted with pomegranates: the seeds of this fruit are fragile when crushed. On the other hand, under the skin, they are set like rubies and embody the strength of humanity if it were united.

Next comes a series of climbing plants, treated like trees by using metal stakes or bamboo, to create a small forest. These alignments of different varieties of jasmine and red bougainvillea (the color of blood in life) are intended to perfume and delight visitors. I have provided two tables and some benches in olive-colored marble to allow for moments of meditation, prayer and conviviality. I have also installed solar energy for lighting and drip irrigation.

ROSE ISSA: What are the different stages involved in recovering the bodies?

RACHID KORAÏCHI: Given my status as a civilian and a foreigner, there is no question of my being allowed to touch the bodies. The corpses washed up or found at sea are recovered by the National Guard, who photograph their faces and any jewelry, tattoos or scars, because they rarely have any identity documents on them. They are then taken to the medical examiner. The prosecutor issues the “right to burial” order. They are then transferred to Gabès hospital, 150 kilometres from Zarzis, for a DNA sample. Given the state of putrefaction and dismemberment of the bodies on their arrival, a large morgue and DNA sampling room had to be installed to save the deceased the long round trip to Gabès.

Today, we are waiting for authorization from the Ministry of Health to take the DNA samples.

ROSE ISSA: This Garden of Africa isn’t your first garden project …

RACHID KORAÏCHI: No. The first garden I created as a form of artistic expression was in Chaumont-sur-Loire (France) for the 8th International Garden Festival, at the request of its director, Jean Pigeat. For this Garden of Paradise, I was inspired by the book The Conference of the Birds by Farid al-Din Attar, the 12th-century Persian poet and mystic. It was in the ceramic workshops of Saint-Quentin-la-Poterie (home of the Museum of Mediterranean Pottery) that I made basins, walkways, water pools and meditation benches.

In 2005, I created the Jardin d’Orient (Garden of the East) 100 meters from the tomb of Leonardo da Vinci at Francis I’s Château d’Amboise. This is a politically committed work, a tribute to the family members of Algerian 19th-century religious and military leader Emir Abdelkader, who were under house arrest at the castle. Between 1848 and 1852, twenty-five people died there, all buried without individual tombs. I planned a place of memory to honor them — something that neither the Algerian nor the French state had done. When the Emir, together with the rest of his family, was released by Napoleon III, he went to Bursa and then Constantinople (now Istanbul), in Turkey, and finally settled in Damascus (Syria). At his request he was buried next to his spiritual master, Ibn Arabi. The Algerian state subsequently broke its promise and moved his remains to Algeria to enforce its authority.

The design of this garden is symbolic: twenty-five tombs, laid out in three rows of seven tombs and the other four grouped together like a crossroads. Seven large cypress trees, rooted in the earth and rising to the sky as if in flight. Seven meditation benches. A long strip of thyme shrubs indicating the direction of Mecca. The Aleppo stone blocks are shaped to be reminiscent of the Kaaba. In the center, the name of each of the deceased is inscribed in a vertical bronze circle, which projects its shadow onto the base. This shadow, following the path of the sun, evokes the pilgrims’ seven circumambulations of the Kaaba.

I have also launched a biosphere project, Dar Al Qamar (House of the Moon), in the Algerian Sahara, where my ancestors settled after arriving from Mecca in the 7th century. Seeing that the country’s administration builds concrete housing blocks in the middle of the desert, I chose to demonstrate that houses can be constructed of local materials: desert rose sand, gypsum, lime…

Over 45 hectares of sand dunes, I created an oasis: 1,200 palm trees, pomegranate trees, citrus trees, pistachio trees, a series of greenhouses for market gardeners (with melons, watermelons, peppers, chilies, etc.). There are peacocks, ostriches, gazelles, camels, donkeys… Several water wells have been drilled to provide drip irrigation and gravity-feed a huge palm grove. All the architectural designs for the large house respect traditional construction methods, where domes and arcades face the sun while creating coolness and shade.

ROSE ISSA: Do you have other memory garden projects?

RACHID KORAÏCHI: Yes, perhaps … I think that whoever doesn’t respect the dead doesn’t respect the living either. This is why I continue to fight for other memory projects. The first, Jardin de la Méditerranée, is on the island of Sainte-Marguerite in the Îles de Lérins, off the coast of Cannes. There lie the remains of Emir Abdelkader’s soldiers and their families, as well as those of Emir Mokrani (revolt of 1871).

The other project, on the island of Fuerteventura in the Canaries, was commissioned by the local aid association for migrants, Entre Mares. I’ve sent the design to the island authorities. So we wait …

I’ve often wondered why I’m creating these homes for the dead when I’m basically an artist. I understood that, perhaps, I had been working on the grave of my brother who drowned in the Mediterranean in the 1960s.

May all those who rest in this place, the Jardin d’Afrique, be my brothers and my sisters, to allow me too to mourn this brother who left a yawning gap in my life and that of my family.

Interview excerpted from the catalogue Rachid Koraïchi: Jardin d’Afrique/Garden of Africa by special arrangement with Rose Issa.