TRANSLATOR’S NOTE: The following text is an excerpt from Karima Ahdad’s Cactus Girls, the story of a Moroccan widow and her four daughters who find themselves homeless due to the vagaries of Islamic inheritance law. The novel is set during the Hirak Rif movement, an Arab Spring–like uprising that took place in 2016–2017 to protest the long-standing neglect and marginalization of the Rif region in northern Morocco. Ahdad uses the Hirak protests to highlight the unemployment and injustice faced by Moroccans in this region and dramatizes the failure of state institutions such as the education system, the courts and health care to help ordinary people.

While Ahdad takes aim at religious fundamentalism, merrily satirizing Islamic televangelists and exposing the hypocrisy of conventional morality, her primary goal is to expose the effects that gender inequality in Islamic inheritance law has on the lives of women. She approaches her characters, whether male or female, with compassion, illustrating how religion and patriarchy converge to blight not only women’s lives but also those of men. Cactus Girls is a powerful testament to women’s ability to survive and thrive in the face of poverty, injustice, and inequality.

Although Ahdad has not faced legal sanctions for her bold writing, she has received death threats on social media. She writes:

“Banat al-Sabbar touches on a lot of taboos in Morocco. I didn’t actually encounter any difficulty because of the novel, because in Morocco, people who might threaten me don’t buy novels and don’t read them. But I have already been threatened because of the articles I wrote about taboos. When I talked about atheist women in Morocco, I received a lot of messages and death threats. I am not afraid though, and I don’t have a problem with taboos, because these people are cowards and they would not speak if they were not hidden behind the screens of their laptops.” [email to translator]

In this excerpt, Sonya, the eldest daughter of the family, reminisces about her Amazigh grandmother and recalls the extreme hardships endured by Moroccan women of earlier generations.

—Katherine Van de Vate

Tattoos

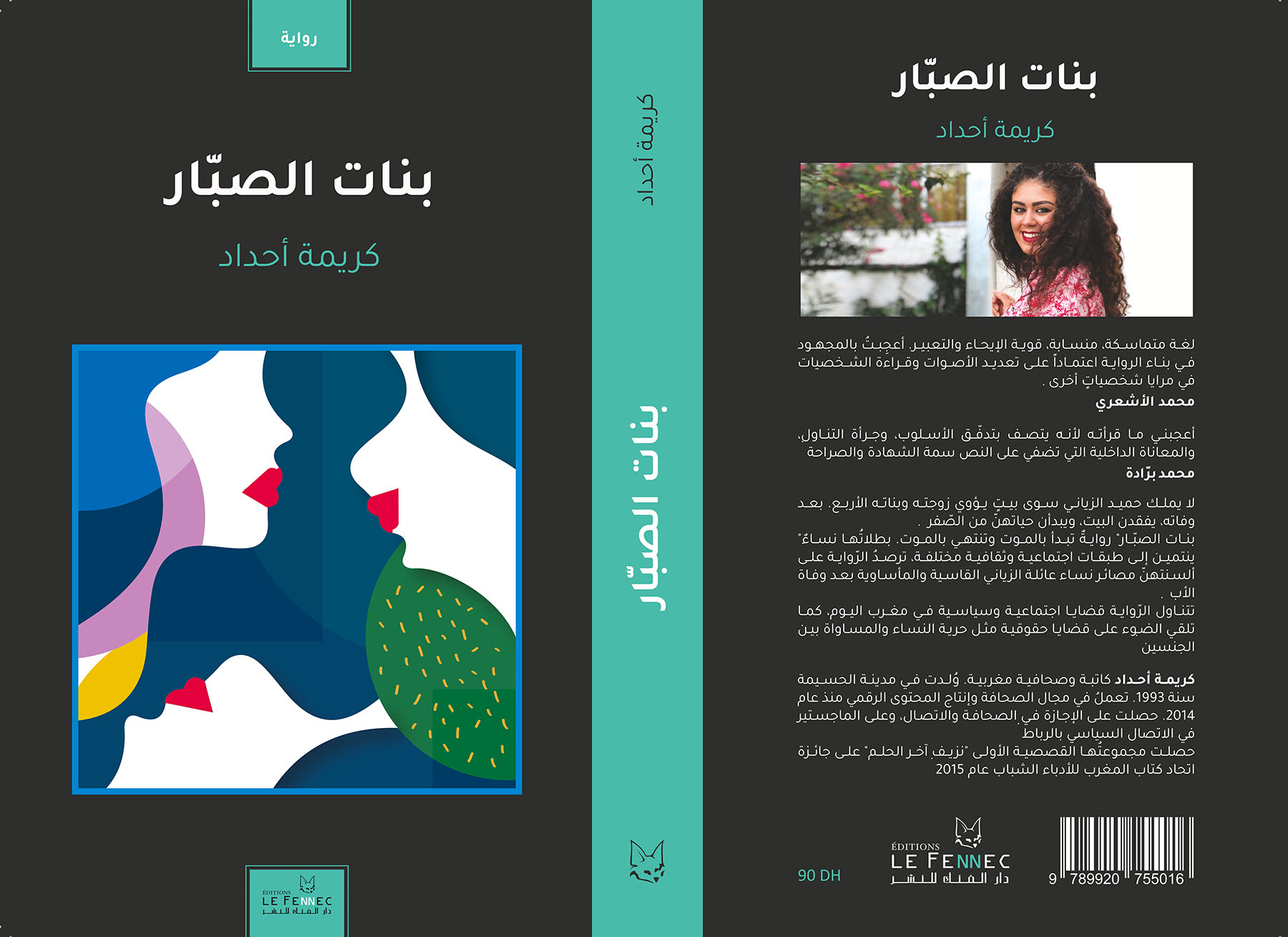

Karima Ahdad

translated by Katherine Van de Vate

When an elderly person dies, we lose part of our history. But in the Rif of Morocco, such a death is catastrophic, because it means the loss of our Amazigh identity, language and culture.

My father’s mother passed away one sad winter in 2011 after an exhausting life of toil and illness. With her death I felt I’d lost an entire history – a chronicle of enthralling stories and anecdotes both true and imagined, a treasure-trove of Tarafit words and expressions that today’s generation no longer remembers.

Only my memories of my grandmother helped me bear her loss. I remember her radiant face mapped with fine wrinkles, the delicate tribal tattoos on her forehead and chin, her hennaed braids, her white palms etched with fine lines, her sweet smell, the stories she chose so carefully for cold winter nights when the wind roared and sweltering summer evenings when the crickets sang. Yes, the death of a woman like her was a loss indeed.

My grandmother lived not a life but a horror film. When she was only three, she was taken by force from her mother. In the Moroccan countryside of the 1940s, it was customary upon a man’s death for his relatives to expel his widow from the home she had shared with his extended family but keep her children. When my great-grandfather died, his widow was forbidden to see her daughter – the light of her eyes, the very blood in her veins – ever again. At the age of five, my grandmother was forced into backbreaking household labour and subjected to beatings, kicking and abuse. She was robbed of her childhood, deprived even of the bread and olive oil whose aroma used to wake her early in the morning. She no longer rose as other children did to find her mother’s appetizing breakfast awaiting her before she went out to play with the chicks in their coop near the family’s house of clay and stone.

In the village where my grandmother was born, the houses were built with clay but people’s hearts were made of stone. Her aunt used to bathe her under the rain gutter, scrubbing the little girl’s fragile body with a piece of coarse burlap that left raw red marks on her soft child’s skin. Although our biology lessons had never taught us that there are hearts of coal, stone or iron, that cruel aunt’s heart was without a doubt made of blackest coal.

It was from my grandmother that I learned about hearts of iron. She told me the story of a long-ago night of horror when her mother returned alone from a distant village to rescue her from the grip of her uncles. The mother ran through the darkness like a madwoman with her long dress floating behind her and slipped into the outer courtyard of the house, where she found her daughter waiting. As she picked her up, a hand gripped the belt of her cloak and pulled her backwards. It was her husband’s brother, “the man with a face of thunder and the head of a snake,” as my grandmother always described him. Fearing he would kill her, she tried to pry off his hand but he held tighter and her headscarf slipped off. As he grabbed her braids, she clutched her daughter for dear life. In a voice of pure hatred, the uncle shouted: “Put down the child – she’s staying with us. Did you really think you could trick us? Thank God I caught you!”

The distraught mother pleaded: “Please let me take my child and bring her up myself, I beg you….”

His face darkening and his scowl deepening, the uncle snarled: “Let go of the child, you thief!”

The mother screamed bitterly: “You’re the thieves! You’ve stolen my daughter to exploit her!”

The uncle seized her plaits and flung her to the ground. Wrenching the child from her arms, he disappeared into the house, leaving the mother prostrate with grief.

Seventy years had passed since that harrowing night, but my grandmother recounted its events as fearfully as if they were happening in the present, not omitting a single detail. Her past still reverberated with such pain that she would continue talking about it until death sank his talons into her soul. My grandmother tore silence limb from limb, eviscerating her life down to its last moment. She had forgotten nothing; she could enumerate the birthdays of every single relative and the dates of the deaths, weddings, circumcisions, divorces, and miscarriages of all her neighbours and loved ones. As she sat on her special couch with the red and white embroidered cover that no one sat on but her, she would list on her short pale fingers when so-and-so had gotten married, when so-and-so had gotten divorced, when this one had miscarried, and when that one had been raped.

Though she had never opened a book or read a word, my grandmother knew her life had been important and she had an overwhelming desire to reminisce about it. Her school had been the sheepfold, the chicken coop, and the broad green fields, where she learned from the gentleness of lambs, the fragility of chicks and the vast arc of the sky. Her teachers were the scratch of burlap sacks and the chill of breezes on her skin when she pastured the sheep at first light, her ragged dresses, scraps of burnt bread and dried fig, and the stench of manure as she mucked out the livestock pens.

Though my grandmother was uneducated, I never doubted that she was the greatest feminist in the world. She fought for a woman’s right to study and work, her right to dance when men were present, and her right to color her hands with henna and her eyes with kohl. My grandmother spent her life battling for her grandchildren to enjoy the pleasures of childhood, reminding her sons and daughters on every feast day to buy their children candy, toys and new clothes, because when people grow up, it’s only their childhoods they remember.

I remember the last time I saw my grandmother. After I went to visit her, she sent me home with sackfuls of fresh fruit and vegetables. What greater sign of love could there be? She had taken all the suffering of her life and transformed it into fierce tenderness and warmth.

It’s from my grandmother, I think, that I inherited compassion, together with my spirit of rebellion, my love of recollecting the past and my passion for living. Like her I adore tattoos, ankle bracelets and rings, kohl and henna, dancing and wide green spaces. I am captivated by the sunset’s rosy face, by the sea, roses and tales of poor girls cast out from their homes and transformed into princesses by a prince’s love. My grandmother was my beautiful princess, though no prince had carried her off. She spent her free time perched cross-legged on her throne – the couch with its embroidered cover – telling stories, eating bread and potatoes, crunching sunflower seeds and listening to the Andalusian music she loved until the lamp of her life went out.

From my grandmother I heard not only about poor girls who’d become princesses, but also the ones who didn’t. When they got pregnant out of wedlock, these girls tore their babies from their wombs with their bare hands, severing the head from the body, before ending up behind bars. These girls had never worn a swimsuit or bra, and by their forties their breasts reached their knees. They had never shaved their legs. Their only make-up was the wooden stick with which they reddened their lips, they’d never seen a sanitary towel, and they cut their hair only once a year, on the feast of Ashura. They shampooed and colored their hair with henna and used it to decorate their hands and feet. Their jewellery was made of cheap agate which they set into bracelets, earrings and necklaces.

These were the girls who had nothing to boast of but their waist-length hair, lush eyebrows, and unsightly bloomers worn under even less attractive baggy dresses. One girl’s relatives brought her a swimsuit from Holland. She put it on, the first time she’d ever worn one. But when she went to the toilet, she forgot to pull it down and soiled it instead.

These were my grandmother’s heroines. They hauled hay, wood, stone and buckets of water on their backs from distant springs. They awoke before sunrise to make their husbands breakfast and brought firewood from the nearby forest to cook lunch. Only after the men had eaten could their wives sit down to the leftovers, and before finishing those they had to leap back up to prepare tea, clear the table, wash the dishes, mind the children and start the supper. Early in the mornings they went out to the fields to till, sow or harvest, while their menfolk, clad in thick warm jellabas, sat around in the local coffee house relaxing with their friends over cups of mint tea, smoking hashish and blowing smoke rings, their hands resting on their long canes. If a man’s son dared to approach him, his father would strike him with his cane to prevent him from disturbing the tranquil atmosphere.

When they reached the age of fifty or sixty, these women began to learn the Fatiha and the rites of prayer. But no sooner had they begun their prayers than they would be distracted or drawn into conversation, turning around at the sound of a nearby voice or chatting with their children and grandchildren. Oblivious to the hushed sanctity of the prayer rites, they spent their time gossiping about everything in their small worlds. If their sons, who had grown long beards to repent their youthful misdeeds, asked them to concentrate and stop interrupting the prayers, the old women would glare balefully at them and retort loftily in their Tarafit dialect:

“Mind your own business! Mimouna th’ssen r’bbi, r’bbi iss’n Mimouna – Mimouna knows God and God knows Mimouna!”*

Having lost all hope of becoming princesses, they grew old. In their seventies or eighties, they would die of the chronic liver, kidney or heart disease or diabetes that their husbands had refused to have treated. After closing their eyes for the last time, they were laid out in their embroidered dresses, their waists cinched with white cords. Faded kerchiefs covered their long orange-hennaed hair, still damp with sweat. Their white palms, seamed with wrinkles and tattoos, were placed gently on their stomachs, and they lay in serene repose, as if they’d been ready to depart this life. But more often than not, their wan faces and downcast features betrayed their grief at leaving before they’d seen all their sons married.

*A saying used in the Moroccan Rif to express that no one has the right to interfere between a person and God.

Katherine Van de Vate is a former diplomat and librarian who translates Arabic fiction into English. Her translations have appeared in Arablit Quarterly, Words without Borders, and Asymptote.