We’re an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality. And while you’re studying that reality—judiciously, as you will—we’ll act again, creating other new realities, which you can study too, and that’s how things will sort out.

—an unnamed Bush administration official, as told to the journalist Ron Suskind

Omar El Akkad

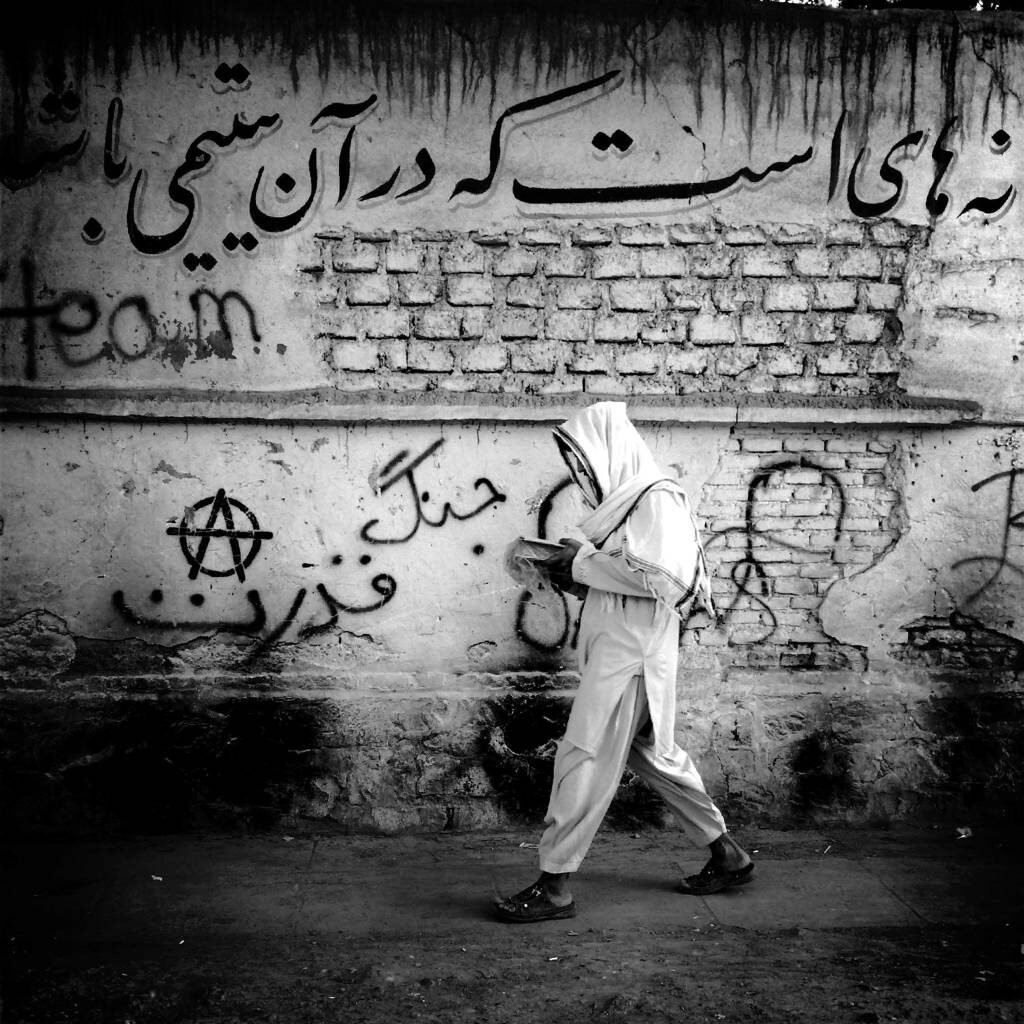

They were just kids. Eighteen, maybe nineteen and skinny, the uniforms hanging off them like drapery. From the side of the road, a few hundred yards past the tank corpses that lined the desert – a scattering of twisted, charred metal that had been there probably since the Soviets’ retreat – we watched them pass the time. They were playfighting. From the back of the truck, they grabbed a couple of the RPG warheads that on this day they were to be taught to fire at the ruined tanks and swung them at each other like baseball bats, giggling. Standing next to me, the Canadian soldier charged with training these boys – newly minted officers of the fledgling Afghan army – gave me a look I’d seen several times during my stints in Afghanistan covering the invasion, a look that seemed to say, These people, there’s no fixing them. I wanted to ask him what he was doing at eighteen, how much of his youth he’d spent in the shadow of charred tanks. I didn’t. I watched the boys instead. The war was still young then, the lie still bright and shining.

Whatever this era is – these last two decades that have cost upwards of one-million innocent people their lives, two decades of mass slaughter predicated in large part on deception and malice for which no one of consequence will ever face consequence – it has overlapped with the entirety of my adult life. I was the same age those boys on the target range were the day I woke up and found an email from a friend of mine – an undergrad at Columbia University – whose subject line simply read: “I’m fine.” A few minutes later I turned on the television and saw the towers fall. Of that first time watching the footage, I remember only a cleaving nausea at the casualness with which physics imposes its will – the planes, in the seconds before impact, possessed fully with the overwhelming violence of the inevitable.

Of course the world would change.

In the days that followed, the government of the United States passed the Authorization for Use of Military Force, a law that solidified President George W. Bush’s right to wage unincumbered, unconstrained war (only a single federal lawmaker, Barbara Lee, voted against the bill, a decision for which she would receive death threats for decades). Almost without fail, every institutional bulwark in American life, every entity from which one could have expected even a modicum of second thought, fell in line.

With hindsight and in the shadow of the carnage that followed, it’s easy to dismiss as frivolous the cascade of performative patriotism that marked those first months and years – the Congressional cafeteria renaming its French fries “Freedom Fries” after the French government under conservative Jacques Chirac refused to support the invasion of Iraq, the editorial cartoons full of crying or stoic eagles and Lady Liberties, the constant appeals from a stream of public figures for Americans to keep shopping. But very little of what came after – the surveillance, harassment and hate-crimes perpetrated against wide swaths of the country’s Muslim population, the establishment of black sites and torture networks and a shadow legal system designed to sidestep the basic tenants of justice, the utter callousness in the face of civilian casualties so long as those casualties were from somewhere else – could never have happened were it not for that initial frenzy of lockstep. They are footnotes now but the few voices that spoke out against this bloodlust, the Susan Sontags and Hunter Thomsons, were either ignored or excised from public life. Of all the glaring wrongs of the post-9/11 years, this is perhaps the one I am most certain we will see again in the aftermath of the next attack, should one happen: a national fealty to violence, inoculated against dissent, and oriented in the direction of vengeance against someone, anyone.

Traditionally, any accounting of the war on terror as a compendium of pain begins with the dead – 2,977 killed in the September 11 attacks and another 900,000 killed in the wars and invasions that followed, though that latter number is more an abstraction than estimate. There are and always will be two kinds of victims: those who are afforded the privilege of moral and statistical specificity, and those who are afforded neither – those whose deaths come at the whims of drones or in the pits of secret prisons or at the hands of a nervous young soldier manning the checkpoint turret; deaths too numerous to count accurately and, anyway, who’s to say these people didn’t deserve it? Who’s to prove they weren’t, in some way too vague to define, culpable?

Beyond lives, the next metric mentioned is almost always money – somewhere in the ballpark of $8 trillion, a meaningless number in almost every respect. One of the most delusional positions in progressive circles is the notion that, had this war not taken place, the United States would have spent the money on healthcare, housing, abolishing student debt.

But neither of these statistical representations of loss can accurately capture the near-unimaginable scope of this era’s negative space – entire generations that could have done and been other things, soldiers who were barely out of their teens when these wars started, and who now watch their children wage it; friends and relatives of those killed on 9/11 who have yet to see the killers face justice despite the U.S. government creating an entire parallel legal system designed to produce convictions; whole branches of the security state created to monitor Muslims as all the while white supremacist violence festered across the country. There is no quantifying what these twenty years could have been, and all the lives that, in the face of this endless aggression, were lived so much more quietly, with so much less joy.

But perhaps the longest-lasting consequence of these last twenty years, the thing that will outlive the current wars and the men and women who waged them, is the normalization of fantasy as a basis of communal life. I used to believe that the defining quote of the post-9/11 came from George W. Bush in an address to a joint session of Congress days after the attacks: “Either you are with us, or you are with the terrorists.” But that infantile binary is not unique in American history, nor to American politics. The quote that has since become a stunning oracle of everything that followed originates instead with an unnamed Bush administration official, as told to the journalist Ron Suskind:

Every way in which the fabric of American public life has torn over the past twenty years has adhered to that unnamed official’s view of the world. From Donald Trump’s hijacking of the Republican Party to the rabid resistance of tens of millions of people to a life-saving vaccine to the utter fecklessness of our national response to the existential crisis that is climate change. Every single disaster, every single failing, owes a debt to the central ethos of the war on terror age – that what you believe supersedes what really is.

There’s a story, probably apocryphal, the senior reporters at Gitmo like to tell about the lock on the media room door. At the time, back in 2008, the room where reporters went to file their stories was located in a large and mostly empty hangar on the base. We were all there to cover the pre-trial hearings for some of the men who had been held at the prison camps for years. There were journalists from all over the globe present, and people were filing at all hours of the day and night. But as per military policy, every night around 9 or 10, the soldiers would lock the door to the media room. If reporters wanted access, they had to go fetch another soldier from one of the tents in the little corner of the base nearby (a place the military would go on to name “Camp Justice”). This policy infuriated the journalists, who despised having to walk for 20 minutes there and back just to get access to the room. They petitioned and petitioned for the military to stop doing this, and finally, after countless bureaucratic hurdles, an officer informed the journalists that a decision had been made to install one of those numerical keypads on the door.

Fantastic, the journalists said. What’s the code?

Oh no, the officer replied. If you want to access the media room after-hours, you go get the soldier on duty, and they’ll enter the code.

It was that kind of place.

No fantasy survives unaided by language, and it was in Guantánamo Bay where so much of the lexicon of the war on terror was perfected. Nobody was ever interrogated here, the prisoners simply had “reservations” in wooden shacks at certain times of the day and night. In fact, there were no prisoners, only “detainees.” And when some of those detainees went on a hunger strike to protest their indefinite confinement in cells that were often not much larger than a broom closet, they never went on a hunger strike at all, they conducted “asymmetric warfare” against their captors.

It’s a testament to the success of this shadow language that these terms no longer need to be stated at all, for they have wormed their way into the public consciousness. At the time of this writing, in its final act before withdrawing fully from its ruinous misadventure in Afghanistan, the U.S. launched a drone attack in Kabul that killed 10 people. A subsequent New York Times investigation indicated the target of that attack, whom the military described as an “imminent threat,” was probably an aid worker. But in reality, the terms “enemy combatant” and “collateral damage” hang over every single person killed this way, every wedding party vaporized, every “surgical strike” turned not so surgical. So total is the dehumanization of more than a billion people on this planet that the terms created to facilitate their dehumanization have become redundant.

It’s largely forgotten now under the weight of the many, many scandals and outrages that followed, but early on in his presidential campaign, Donald Trump mused about making American Muslims carry special identification cards. As expected, several high-profile Democrats condemned the idea. But the primary counter-argument on which so many of these Democrats relied was not moral or ethical, but pragmatic: forcing Muslims to carry such cards, they argued, would alienate a community that is a vital ally in our efforts against terrorism. Not an appeal to the obvious connection between such policies and some of the darkest chapters in human history, not a denouncement of the obvious unconstitutionality or immorality – no, this wasn’t about the basic rights of a group of human beings, this was a chess game, and someone had made a bad move.

It is a straightforward if nonetheless controversial fact that over the past twenty years, the two central and monstrous forces of this age have succeeded beyond their wildest dreams. The terrorists who set out to fracture the load-bearing beams of American democracy can look now upon a country at war not only with so much of the world, but with itself, its police forces militarized with the leftover arsenal of its overseas conflicts, its enshrined freedoms under constant internal threat. And in its response, the Bush administration and each one of its successors have managed to maintain the conditions for an alternate reality in which the United States exists in a state of permanent war, the enemy endlessly interchangeable, the consequences negligible.

There is no greater evidence of this success than the simple truth that the people responsible for an illegal, unnecessary war that killed hundreds of thousands and destabilized entire regions of the planet have never once been held to account.

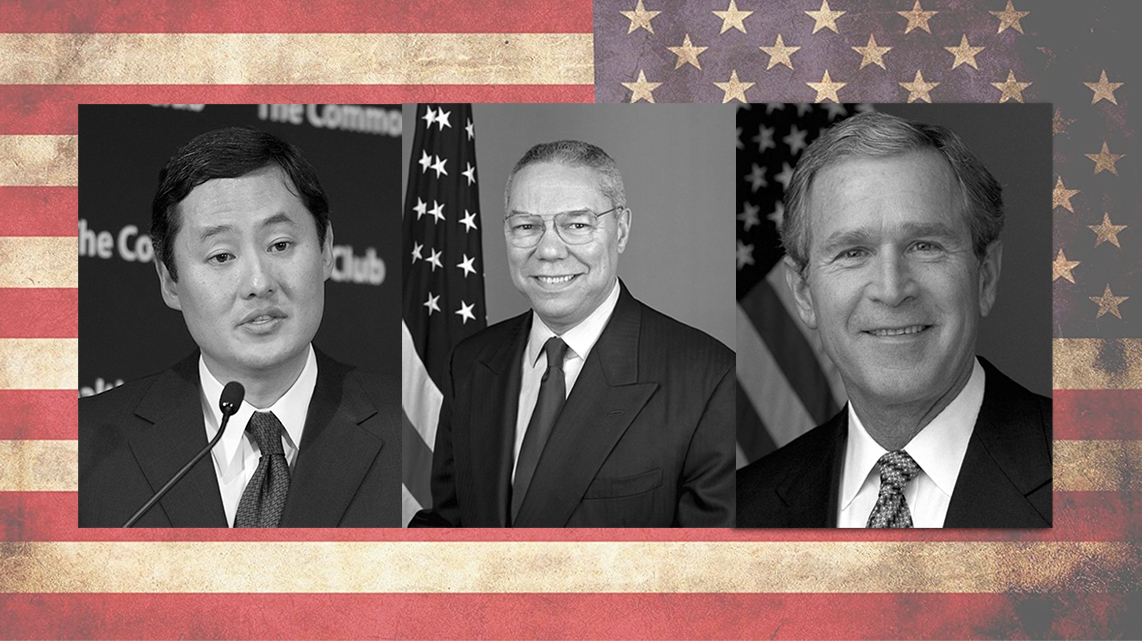

The man who authored the torture memos now holds a comfortable professorship at Berkeley.

The man who lied about Iraq’s nuclear capabilities before the United Nations now makes lucrative speeches and sits on the boards of tech companies.

And the man who oversaw it all now leads a quiet, dignified life, playing elder statesman and painting portraits of immigrants.

Meanwhile, some of the men who spent the better part of a decade in those tiny cells in Guantanamo have just assumed control of Afghanistan’s government. Osama Bin Laden is dead, a few of the 9/11 architects languish in permanent detention, some of the American soldiers who killed and tortured with impunity in Iraq and Afghanistan have been subjected to legal proceedings of one kind or another, and whatever Al Qaeda was, it no longer is. But in every other respect, evil won.

Torture is at the Nasty Center of the 9/11 Case at Guantánamo, by Lisa Hajjar

We almost died that day, out in the target range. Those boys, when it came time to practice, did the best they could with what they had. But the equipment was ancient – not the weapons the NATO troops carried, but a mess of mismatched guns and ammunition. The truck-mounted machine gun jammed when, apparently, a wayward soviet bullet refused to cooperate. When it came time to fire the RPGs, we stood and watched the soldiers aim at the tank corpses. But the weapon was a dud – instead of hitting the target a few hundred yards down the desert, the warhead plopped on the ground about fifteen feet from us. We ran for cover, but the fact that we had time to run at all meant we’d gotten lucky, the grenade failed to detonate. Perhaps it was also shoddy, a remnant from a previous war. Perhaps it landed too softly. Perhaps it was just luck.

It is customary to end commemorative pieces such as this one with something hopeful or at least prescriptive. Here it is: the people responsible for conning this country into a twenty-year campaign of bloodshed and futility, even if it is naive to imagine they’ll ever face legal consequences, should at least never be allowed a role in public life again. The relics of this age, chief among them the camps at Guantánamo Bay, should be shuttered, and the inmates that can be tried should be tried by the American legal system, which is perfectly capable of doing so, and not some half-baked shadow court designed to sidestep the constitution. The places where the ruinous legacy of these forever wars has seeped into domestic life, the militarized police agencies and rampant demonization of whole communities, should be recognized as their own forms of terrorism.

None of this will bring back the wasted years, or undo the damage to those who lost loved ones, those who came back from these wars broken, or never came back at all, those who were killed because a drone operator on the other side of the planet couldn’t tell one brown person from another, those who quietly changed their names to something less foreign-sounding, those who’ve waited years for something remotely like justice. But it may prevent the next decades-long catastrophe. Having bought fully into the fantasy-construction model of the war on terror years, one of the two major political parties in this country now trades almost exclusively in these delusions, and it’s only a matter of time before we are subjected to the next round of fraudulent reasoning for war – be it in Lebanon or Venezuela or any other part of the world whose failing institutions create the prerequisite misery for violence and whose populace is deemed subhuman. It will look a lot like the last time – the jingoism, the lockstep – and should we allow it to happen again, every last one of us will be complicit.