Melissa Chemam

As I discussed in my past two columns, traditional Arab music has never stopped influencing modern and pop music, deeply impacting new musical movements in the diaspora, including disco, electronic music, rock and other genres. A country that has especially benefitted from these influences, through migration and cultural exchange, is of course France.

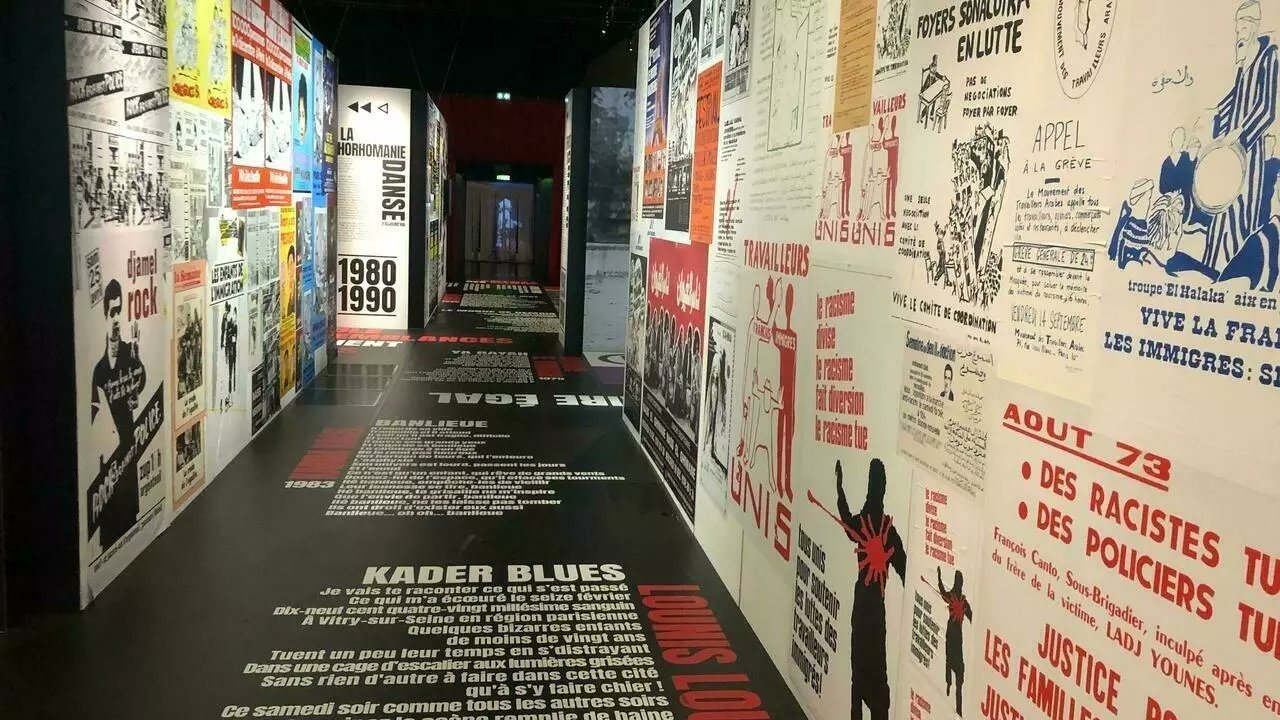

In view of the current pandemic restrictions, my usual habit of traveling across seas and continents has been heavily disrupted, so instead of spending New Year’s Eve in Cairo or Tunis, as in previous years, this year I only traveled back home, to Paris and Marseille. But, uncannily, this trip offered an occasion to immerse myself in musical musing thanks to a unique exhibition: “Douce France: Des musiques de l’exil aux cultures urbaines,” which opened mid-December in Paris at the Musée des Arts et Métiers.

The title refers to an old French song, “Douce France,” written and popularized by Charles Trenet in 1943, and inspired by the country’s oldest poem, an ode to the coming of its modern form as a state. But “Douce France” also refers to a more recent and revolutionary version in an Arab rock interpretation, created by Rachid Taha and his first band, Carte de Séjour, released in 1986.

The exhibition centers around the personality and achievement of Rachid Taha, who was born in 1958 in Algeria, and died in 2018. Taha is well-known for pioneering a form of Arab rock starting in the 1980s in France; he later achieved international fame, collaborating with new artists abroad, including Rolling Stones producer Don Was, Femi Kuti and Mick Jones from The Clash. He was also a committed activist who, throughout his career, called for tolerance and decried the rise of anti-Arab and anti-Muslim xenophobia in France and Europe. To quote the museum, the exhibit “revisits the artistic emergence of the so-called ‘beur’ generation, a symbol of the mixed and joyful integration of a youth of immigrant origin.” It also looks at the emergence of “beur”-driven social movements that characterized 1970s France.

Rachid Taha arrived in France from Algeria with his parents in 1968. He spent a number of years in an impoverished working-class immigrant community in the east in Alsace, and then in the Vosges, before moving to greater Lyon, where he began to establish his reputation. Taha’s musical influences, however, informed his tastes even before emigrating, for as a child he had learned Arabic before being forced to switch to French, and early on was fascinated by the iconic Egyptian singer Oum Kalthoum. In Algeria, he had already been fond of local music, especially raï and chaabi, the traditional street music of Algiers, formalized by El Hadj M’Hamed El Anka, and more generally by 1960s performers from across the Maghreb.

The “Douce France” exhibit opens with this music, first with the sound of Dahmane El Harrachi. Born Abderrahmane Amraoui in Algiers, he moved to Paris in 1949, worked as a factory employee and continued performing and recording. He later popularized chaabi music there in the 1960s.

The exhibition mixes photographs with sound installations, and also recreates the environments in which these musicians evolved, with for instance a copy of the tables and chairs of Café Scopitone, in the Parisian neighborhood of Barbès, where most of the Arab immigrants used to gather and play music, like the singer Salah Sadaoui. It also mentions the unforgettable songs of Kabyle singers Lounis Aït Menguellet and Idir.

Many women contributed to this exilic music scene, hoping to record their songs with such Parisian record labels as Pathé Marconi. The dancer Sheherazad and singer Noura are for instance shown in gorgeous black and white photographs, performing regularly in Cabaret El Djazair, rue de la Huchette, in the Latin Quarter.

Covering subsequent decades, the exhibition recreates the suburban environment where Algerian immigrants grew up, near Paris, Lyon or Marseille, brewing new sounds of their own by mixing their parents’ favorite artists from Algeria and Egypt with the various sounds en vogue in Paris at the time — electronic music, early hip-hop and of course punk and rock.

Punk and rock were the genres that inspired Rachid Taha in his late teens, along with many other young French men and women of his generation. Taha became the first French Algerian to dare to release records of Arab rock music, with Carte the Séjour in the 1980s, then solo.

Two of his all-time hits were covers of Dahmane El Harrachi’s “Ya Rayah” and The Clash’s “Rock The Casbah,” which he later performed live with members of the iconic British Punk Band.

The rest of the exhibition gathers television clips from the late 1980s and 1990s, where the artist can be scene addressing his status of outsider and outspoken voice for immigrants.

I visited the exhibition with my mother, who grew up in Algiers in the post-independence war era, in the 1960s and 1970s, and knew all the artists referenced by the curator, Naïma Yahi, a historian and researcher based at URMIS – Université Côte d’Azur. My mother was especially fond of Idir, an icon of Amazigh music, who sadly passed away in 2020, and still plans to see Aït Menguellet perform as soon as the Covid restrictions will permit.

Reporting on music between France, England and Africa, I also had the pleasure to see Taha perform live quite a few times, between 2009 and 2017, in Paris, and to interview him once. He embodied a mixture of anger and joy, rebellious by nature but also deeply endearing and loving. He truly believed in multiculturalism, and gave many young French immigrants — whose parents felt that Arabs would never be accepted in France — a reason to hope that cultural entente was possible.

The exhibition is on until May 8, 2022, in Paris’ Musée des Arts et Métiers.

(For French speakers, check out the exceptional radio episode of 03/27/021, produced by Rebecca Manzoni for France Inter, on Rachid Taha’s journey: Rachid Taha, “Français tous les jours, Algérien pour toujours.”)