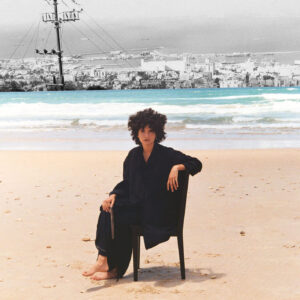

A single Palestinian woman attempts to survive in Berlin without a cell phone.

I love Berlin. It is a filthy, compassionless city that is deferential to neither its long-time inhabitants nor interim visitors; to her all are transient. I’ve always known, ever since my first visit in 2016, that I would return to her time and time again.

Only a year after that initial visit, I was back. My sojourn carried the whiffs of a homecoming laced as it was with the tentative aspirations of settling down. I had traveled from Haifa, where I’d lived estranged in my Palestinian city that only revealed itself incrementally, and even then momentarily, to project an ephemeral Palestine; one relegated to dark corners and narrow alleyways. And here I was, in Berlin, this refreshing place where everything and everyone appeared to be shrouded in foreignness, all of us drifters, where I was never required to answer questions about who I was or what I was doing. A place where the truth of my beliefs was never forsaken.

One day, as I sat in the Turkish market, located in Karl Marx Platz, a pigeon shamelessly defecated on me, its droppings splattering on different parts of my body. I immediately remembered that where I came from this was usually looked upon as a good sign, but since I was now in Berlin, I wondered whether such notions would still hold true. I cannot begin to compare the disproportionate number of times I’ve been shat on by these pesky creatures to the dismal number of times I’ve lucked out after each incident. However, in that moment, possibly perversely buoyed by the heat from the warm shit seeping through my trouser leg onto my skin, I felt surprisingly hopeful that good luck might just be lurking around the corner. Perhaps, I reasoned, luck, like pigeon droppings, struck randomly so that for all the times that I missed it, it could still find me nonetheless.

But, I also couldn’t forget that for every fanciful lucky notion was an opposing harbinger for troubled times ahead. You see, as children we were taught to look for the meanings and signs behind certain things, something which has stayed with me, even though as an adult, I find it totally bogus. Where I’m from, a crow’s signature caw portends misfortune, and its black color foretells a death. And yet, here in Berlin, that condemned raven has been my one and constant companion, especially on gray, gloomy days, when the skies have been dense with clouds. This crow, one of many, would arrive to perch itself on the iron banister of my high-rise apartment balcony, and with its squawk and the pitter patter of its claws would delight me to no measure. As soon as I saw it, I’d call out to it, imitating its sound. Soon, though, I found I was persisting in the act even when there were no crows around. I cawed at my friends, alone at home, and even when I spoke on the phone.

Last summer, my cell phone stopped working as if it too wished to withdraw into oblivion. As with everything else, it abandoned me without remorse, leaving no replacement in place. I feigned nonchalance, meeting its silence with my own and placed it in a drawer to rest in peace among long abandoned papers. I decided not to replace it, unaware of the gravity of this brazen decision.

And so I set off to explore this city that regards everything transitory after a cursory check on the soundness of wandering around in a city, like Berlin, without access to a cell phone.

Understandably, I found no problem navigating the familiar places to which I had been many times before, thanks to the map application on my phone. I had, in fact, memorized the names of certain streets as well as those of train stations alongside their numbers and routes. I was able to recall the total number of stations between point A and point B and the actual time it took to get from one to the other. Unsurprisingly, it was when I decided to steer away from the familiar that things got more complicated. How do I find where I’m going without getting lost? How do I let someone know that I am going to be late because I’ve lost my way? (I don’t) How do I apologize for not showing up when faced with an emergency? (again, I don’t) How was I to get in touch with my family, friends or even colleagues? (by email, and only when necessary).

It seemed as if I were living back in the days when homing pigeons had been used to deliver and receive correspondences. I found that I was shockingly elated. And although my social life took a nose dive, reconnecting with myself was doing me a world of good. I was finally listening to that internal voice that had pleaded with me, for years, to pay attention to it and that I had allowed the bustle of life to override.

Then I needed to get a rapid Covid test. I arrived at the lab unannounced, and pushed through the door as if I were about to surprise my family with my sudden appearance. However, judging by the receptionist’s unwelcoming reaction, you’d think, in fact, that I had been breaking an entry.

“Hello! Where are you headed? Do you have an appointment?” the receptionist hollered.

“Can I make one?” I asked, feigning a calm and gullible demeanor.

“You’ll have to register first,” she said.

I made to head to her desk to do just that but she soon put a stop to that.

“First, you need to go outside, scan the QR code to access the registration page. After that’s done, you can log in to the system to schedule an appointment,” she explained.

“Hmm,” I muttered. “I haven’t got a phone,” I said.

The woman looked at me in bewilderment. It seemed like she couldn’t comprehend what I was saying. Recovering her professional demeanor, she explained that the process could only be carried out electronically, although it still required my actual ID card. Luckily, I had brought that with me.

Suffice to say that all my attempts to persuade the woman for an appointment amounted to nothing. The operation could not be completed. The employee’s adamant resolve that things could not take place, was further proof that in today’s digital age, in which robots and artificial intelligence rule, logic and common sense were nothing but antiquated concepts of bygone times. We now lived at the mercy of a confusing era that allowed no departure from the rules, and opted to squash all dissidents and deviants that challenged authority.

I returned home defeated and deflated, knowing that I would not be able to go out again. It was turning out to be a lonesome and tough day, one suited only for staying in, and contemplating my state of affairs. All I desired was to be alone with my thoughts. Besides that, a feeling deep inside me wished to latch on to this peculiar predicament — instigated by a rebellious phone — as further excuse for my constant introversion where I could safely observe the world from afar. For in distancing oneself from reality, one is better able to understand it and therefore to respond to it.

One fine day, I remembered that my friend had gifted me a toy, one similar to the one we used to play with as children. It was a small flat and rectangular encasement, made of plastic, that housed five tiny round beads. At its base were five tiny slots and the whole thing made a beeping sound each time I moved it. In order to win the game, I had to maneuver the contraption in such a way so that each bead would move to occupy an empty slot. Once all five beads were placed in the available slots, the game was over. It was an infuriating game, since no sooner did I manage to get one bead into its position, than another one escaped, after which, frustrated, I would have to start all over again. I look back and observe how alienated and alone I must have felt on Berlin’s crowded public transport heaving with passengers glued to their phone screens, as I in turn was transfixed to my own beeping version of a screen, struggling to home those beads.

Soon though, the beeping sound became a familiar one. As I walked around the city, I could hear the muffled ding emanating from inside my handbag. I always carried the toy with me and when I switched bags, I always made sure to take it with me. With time, the dinging represented comfort and reassurance, especially on those nights when I walked home alone. Like the bell a shepherd hangs around a goat’s neck to find it when it goes astray, I wondered, whether I too, would be found in the midst of my wandering, shepherded back to safety.

I love Berlin, but sometimes I forget that I live in Germany’s capital. I forget I live in a large, filthy, and savage city, scant of bright corners of relief. And, I forget that I reside under a cold gray sky that titillates the deep recesses of my mind.

I forget all this, and when I remember I become confused.

I consider Berlin a warm and intimate place. The friends I’ve made here come from lands I can only dream of visiting because of the banalities of borders, passports and the stupidity of those who decree witless laws. And yet, from this small place, a part of me feels that I’ve already been to all these places and experienced them through the eyes of my friends and the stories that they tell.

![Fady Joudah’s <em>[…]</em> Dares Us to Listen to Palestinian Words—and Silences](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/SAMAH-SHIHADI-DAIR-AL-QASSI-charcoal-on-paper-100x60-cm-2023-courtesy-Tabari-Artspace-300x180.jpg)