Mediterranean Fever releases in France and select European territories in December 2022.

Viola Shafik

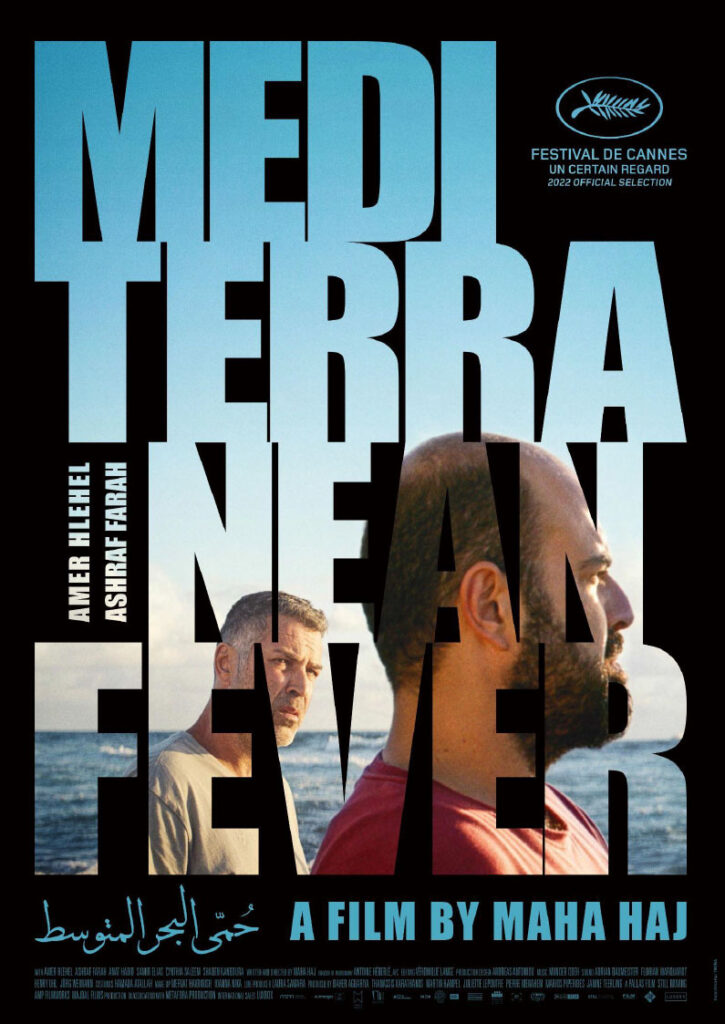

“Can’t choose whether to drink tea or to hang myself.” With this opaque but surely self-ironic quote from Anton Chekhov’s writings, Palestinian director Maha Haj preludes the last scene of her feature film Mediterranean Fever (2022). Her central protagonist — Waleed (Amer Hlehel), a melancholy husband in Haifa — leaves this sentence hanging on a computer screen after exiting the frame. Premiered in this year’s Cannes Festival as part of Un Certain Regard, we caught the CINEMED screening of Haj’s film in Montpellier in October, where it played to a highly receptive audience, one that welcomed every screening with rhythmical clapping and a cheer. The audience was thus in the mood for some good laughs and in the end showed much appreciation for the film’s insights into the complexities of Palestinian male psychology, played out quite subtly within the framework of an invisible absent-present Israel.

Thus, while being entertaining, well written and masterfully staged, the story itself is filled to the brim with human and political abysses. It focuses on two very different male tenants of a modern Haifa apartment building. Neighbors Waleed and Jalal (Ashraf Farah) are both married and fathers of underage children, who find themselves in an unexpected entanglement, not far indeed from a typically Chekhovian construction where the humorous absurdities of the human condition foreground the diluted action. Little wonder, over the course of the film the two protagonists, a wannabe writer and a half-criminal day laborer, start almost indiscernibly to switch roles in a scuffle around fear and courage, life and death.

A dark comedy? Yes, and a buddy film in a genre that, interestingly, has been authored and directed by a woman. Haj’s declared objective was to reflect on the situation of the Arab citizen in Israel. In the Q & A following the screening, she explained she wanted to break with expectations that a female director would turn preferably to female stories. Regardless, this is still a film about gender as defined and shaped by social and political circumstances.

Waleed, the unsuccessful depressive writer and Jalal, the outgoing, seemingly tough crook both lack the evident stability of their wives, who bring home the money, and hold the family together. It is an obviously middle-class milieu in which they are situated that also informs their moral and psychological constraints and double standards. Jalal, the typical male parasitic big mouth, cheats on his wife but is exposed to the threats of a gang to whom he owes money. Waleed, a kind and caring father, is marked by a depression that makes him want to sleep all the time. When he manages to get out of the bed or stand up from the sofa he tries as best as he can to support his breadwinning wife in cooking, washing, cleaning and taking the children to school. Even though Jalal is often out of the house, walking his two aggressive dogs on Haifa’s streets, he starts to feel empathy with Waleed — particularly after the latter breaks down with a panic attack in a carwash. The reason why they meet? Surprisingly, Waleed turns to Jalal to find him a killer.

The multiple layers of these two highly nuanced characters is found in their immensely successful performances, with Ashraf Farah as Jalal and Amer Hlehel as Waleed — a dramaturg himself, Hlehel was involved from early on during the writing process of the film. One of the most hilarious scenes pictures the men during a phone conversation: Waleed is filling the washing machine and Jalal on the other end washes the dishes while they discuss how to find a suitable killer for Waleed. The repertoire of genre cinema, the planning of a crime usually associated with public and dangerous spaces, as we know from male dominated genres like thriller and police films, gets subverted here and paired with home and family; that is, the realm of so-called women’s films, including melodramas. It is here also where the table turns between the two characters.

When Jalal hereafter invites Waleed to a nightly hunting excursion and exposes his great talent in shooting wild boars, Waleed comes forth with a shocking proposal. First, he confesses that he is actually looking for a killer to help him execute his suicide. Then he wants Jalal to be that executioner. The answer is harsh: “Suicide is cowardice,” says Jalal. No, counters Waleed, “I don’t fear death!” Obviously, he is more afraid of life and the reactions of his family to his wish to die. He insistently tries to talk his buddy into the affair by offering to cover all his debts. In what follows, Waleed will put the full range of his manipulative talents on display and affect Jalal’s life deeply.

At the same time, the socially dysfunctional wannabe writer is characterized as the one with the strongest political consciousness, hereby juxtaposing male vulnerability and resilience. “Palestine, you can forget about” (Filastin! billaha weshrab mayitha) declares Jalal, using a metaphorical saying (lit.: soak it and drink its water!). Not so Waleed, who constantly admonishes his teenage daughter to speak Arabic and not Hebrew. Moreover, there is this mysterious malady that his son develops: every Tuesday he is sick and needs to go to the doctor. As the latter suspects this might be the “Mediterranean fever,” a virus prevalent primarily in the Eastern Mediterranean, as Waleed discovers in a real trigger moment. His little boy is constantly avoiding the geography lesson where in following his father he clashed with his teacher who declared al-Quds/Jerusalem to be the capital of Israel.

The Struggle for Palestinian Identity

Indeed the film depicts an all Arab society, a ghetto in fact, for the only person who appears and speaks Hebrew apart from Waleed’s teenage daughter is the above mentioned Russian pediatrician. Otherwise not a single Israeli Jew is to be seen. This isolationism reflects also in the film credits. Almost none of the film crew has a Hebrew name. Plus, in refusing to accept any Israeli funding, the director gave herself the freedom to list her film in international film catalogues as Palestinian. This sounds like a trivial affair. However, it is not. Plus it shows that Haj in fact does not want to soak and drink away Palestine.

Since the clash around Suha Araj’s film Villa Touma (2014), the matter of national affiliation has become an even more serious and contested question for Arab filmmakers who have grown up in today’s Israel or historical Palestine, in the times of Elia Suleiman and Michel Khleifi, both expats who largely coproduced their films with Europe. As the New York Times coined it quite poignantly, “The Hand That Feeds Bites Back.” When Suha Arraf dared to identify her film as Palestinian at the 2014 Venice Film Festival, the Israeli Film Council objected and asked her to return the more than $500,000 in funding she had raised from different Israeli sources. She was heavily attacked, even insulted and criticized for a “lack of integrity,” according to the Time story. Her move was understood as a “collaboration with the trend of delegitimizing Israel and its existence.” Since then, for Arab Israeli filmmakers, the polarization around their listed identity has increased to the point of either money or national affiliation.

Mediterranean Fever hereby taps into that politically charged affair, first of all on the infrastructural level. Yet on the cinematic level, too, there is a part in the film that departs from its Chekhovian lightness to encompass the “collective depression” as compared to the virus the film’s name carries. While this “virus” is almost ironically dissected with Waleed’s character, a crucial and merely visual, or better spatial, insert during the finale corresponds rather to what Gilles Deleuze might have called an affection-image. After a sad turn (not to be disclosed here to avoid spoilers) the ending shifts to an impressionistic sequence totally unrelated to the action, in the modern building in which the protagonists live, where their comfortable apartments are left behind to move to a totally uninhabited locality. Accompanied by non-diegetic musical ode to Virgin Mary (one of the characters is Christian) we see elegiac images of dilapidated deserted buildings of traditional Palestinian architecture, from the old partly abandoned Haifa Arab neighborhoods of Wadi Saleeb, Wadi Nisnass and Halleesa, wilfully neglected since 1948 by Israeli authorities. These are followed by the deserted beach, the view of the sea from port of Haifa, and the ships aligned on the horizon — a place of nostalgia indeed. The latter term, if we believe the dictionary, has been explained as “a mood triggered by uneasiness with the present and filled with indefinite longing. It expresses itself in turning back to a past time transfigured in the imagination.” This is the Mediterranean fever in Haifa.

Coming soon in TMR are an analysis of the Tunisian film Ashkal, winner of the CINEMED jury prize, in the context of a wave of Tunisian dystopian cinema, along with a discussion of the controversial scope of voyeurism in the oeuvre of Tunsian filmmaker Abdellatif Kéchiche.