Over the last decade, Europe’s largest population of Arabs and others from the MENA region has shifted from London to Berlin, but will London’s Middle Eastern cultural scene survive the closing of Al Saqi Bookshop, as well as the folding of Banipal Magazine and the departure of the British Museum’s Venetia Porter, who devoted her career to showcasing Middle Eastern art?

Malu Halasa

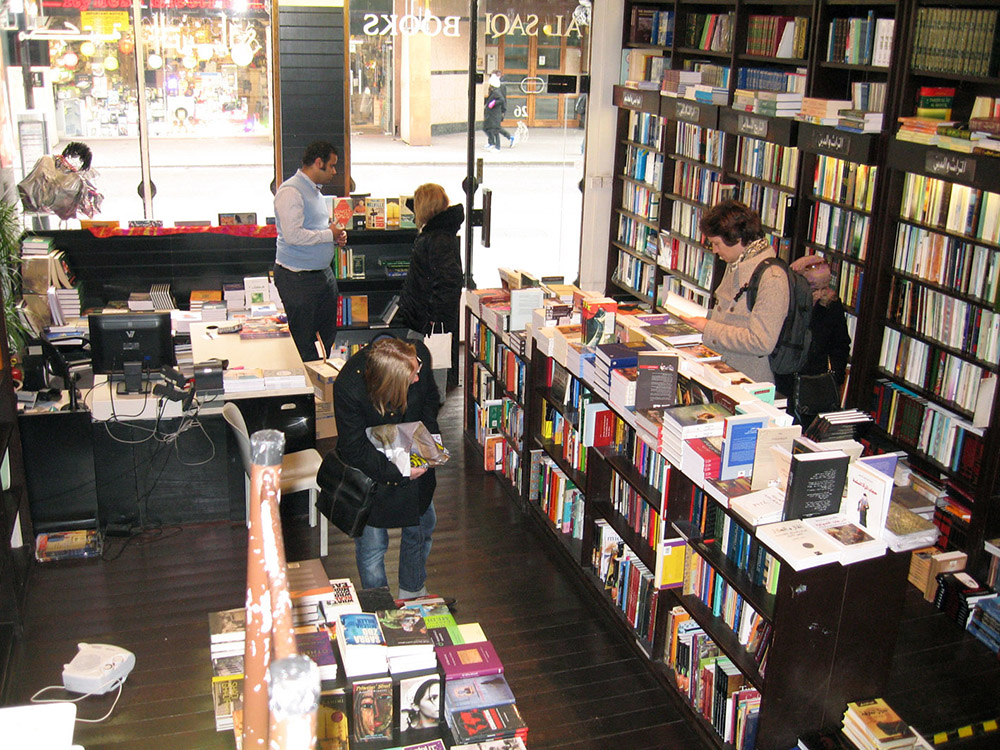

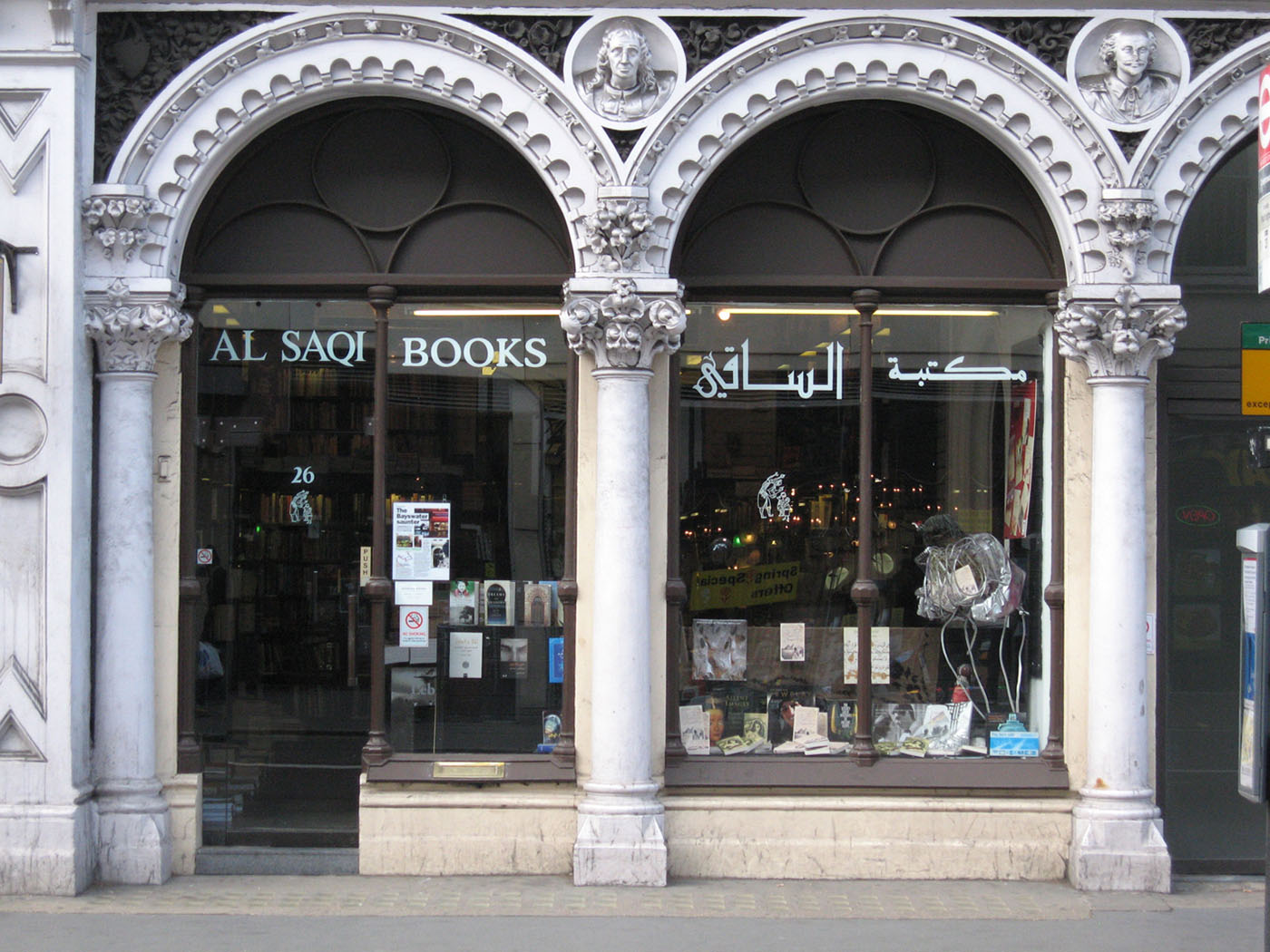

A quiet revolution started when Al Saqi Bookshop opened its doors in the late 1970s. The first Middle Eastern bookstore in London challenged the then-pervasive notion that a region scarred by war should be understood only through the prism of winners and losers: that terrorism, not occupation, was behind the violence in Israel/Palestine; and that totalitarianism, religious and otherwise, was the sum total of a diverse region and people. Al Saqi was the first Arab bookstore I entered where Islam was not front and center. Run by women, the bookshop revealed a diverse, dissident and culturally lively Middle East.

Through the novels on its shelves, I conducted my own personal survey of Middle Eastern fiction. While old men gossiped in Arabic out front with Amin, one of the bookshop’s legendary assistants, I hung out by the desks of bookseller Salwa Gaspard and publisher, artist and Renaissance woman Mai Ghoussoub (1952–2007). There, I learned about the latest Middle Eastern authors, music, art and film. Al Saqi Bookshop was the place of refuge I retreated to after the shock of 9/11. It was where, in 2004, my early ideas for the anthology Transit Beirut were honed. By 2014, those discussions had culminated in Syria Speaks: Art and Culture from the Frontline.

At Al Saqi, identity was complex and multifaceted. Much of mine had been formed from my family roots in Jordan and the Philippines, and growing up mixed race in the U.S. At various times I had to admit I was an uncomfortable Arab. Intellectually, emotionally, Al Saqi Bookshop left a mark of inclusivity on me, and encouraged me to become the writer I am today.

Earlier this month, I went to the already closed bookstore. Mai Ghoussoub’s sculpture of Om Kulthum, with its iconic sunglasses and beads, graced the window. Inside, the shop was dark. As I waited outside, a deliveryman carrying flat-packed cardboard boxes banged on the door. Eventually, Salwa Gaspard appeared and ushered in the deliveries — and me.

In the Beginning

With her husband André Gaspard and friend Mai Ghoussoub, Salwa fled Lebanon’s civil war and came to London. During our conversation, she recalled that in 1979, when the three of them opened the bookshop, they found “many Arabs but not much Arab culture.” In the early days, to drum up business, Mai scoured the Yellow Pages for Arab and Arabic-sounding names, and sent them a list of titles available for purchase. “Usually it was only one page because in those days the bookstore was so small,” she said.

In the early 1980s, the bookshop became a hub for London’s Arab diaspora — sometimes for the wrong reasons. “The community felt like it was their home. We were a citizens’ advice bureau for the Arabs,” laughed Salwa. “They would come and ask us to find them nannies. Before they spent their summers in the south of France, they wanted English-speaking nannies, and they thought that we could supply this.”

But the project of the three political activists from Lebanon was more ambitious than that. As Salwa admitted, “We were not very commercial, but we knew culture and we knew books. We were always intellectual people, and from the left as well, even though we didn’t belong to the same parties. We wanted to replicate the Lebanon we dreamed of — one that was open minded, cultured and had no censorship.”

Among its shelves you could find all sorts of books, from Israeli art to the latest critical theory on Islam. Inside the shop, the middle section of shelves was piled high with books showing on their spines the distinctive Saqi logo of a water seller. These, published in Beirut by Dar al Saqi, the sister publisher of the bookstore’s original imprint, Saqi Books, were going to be packed into those cardboard boxes and returned to Lebanon. The novels I once perused on the shelves and the bilingual editions of poetry and short stories I selected from the low-lying coffee tables and sent to my father Adel and aunt Rugda in Akron, Ohio, were long gone; they had been picked up during the store’s last fire sale. The English-language books that were left were destined for another U.K. bookseller.

Still, at this late date orders kept coming in. A grand dame had just heard the bookshop was closing, called Salwa, and said there was a book she couldn’t live without. Of course, numerous boxes would have to be opened and the volume searched for. Journalists, academics, artists, curators and political pundits befriended the bookstore in its 44 years of existence, and everyone I spoke to felt bereft at its closure. Myriad factors contributed to the bookstore’s demise: Brexit, the subsequent avalanche of customs paperwork, the high cost of shipping, a mysterious “Covid tax,” not to mention the fall of the dollar in Lebanon, where Saqi Books and Dar al Saqi often printed their books.

Saqi Books

In 1986, the bookstore launched the publishing house Saqi Books to fulfill a need in the British market. “At the time,” said Salwa, “we were puzzled that hardly any translations of Arabic writers existed in English — as opposed to France, where Arab writers were being translated into French and are still being translated much more than in the U.K.” [One in six books published in France today result from translation. —ED.]

The sea change they expected in British reading habits after the 1988 Nobel Prize in Literature, awarded to the Egyptian novelist Naguib Mahfouz, never materialized. Two years later, the Egyptian writer’s British publisher nearly dropped him. The 2021 Nobel Prize winner for Literature, Abdulrazak Gurnah, also endured the fickle nature of publishing. His English publishers had let his novels fall out of print, but then rushed to reprint them following news of the prize.

Britain may be the home of Virginia Woolf and T.S. Eliot, but its bestseller lists are routinely dominated by books about cooking and the royals. The week before last, Spare, by Prince Harry, sold 400,000 copies the first day of publication. With a twinkle in her eye, Salwa observed, “And one year Karl Lagerfeld had a book about his cat and it was a bestseller.”

Despite the vagaries of the British book trade, Al Saqi Bookshop carved out an important niche, and sold books not just in Britain, but also in Europe and the Gulf. The store’s success paved the way for a new publishing venture in Beirut. “André saw so many subjects he didn’t find in Arabic publishing,” said Salwa. “He thought there were many opportunities.” Dar al Saqi translated and published all the books of Hannah Arendt in Arabic, and now it is publishing books written by her second husband, the philosopher and poet Heinrich Blücher.

Censorship and Piracy

Because they print and sell in Lebanon, censorship has always been a problem for both the bookshop and its publishing imprints. In the 1990s, Al Saqi imported art books from the esteemed German publisher Taschen to sell at the Beirut Book Fair.

“Once, we took a book called American Architecture, and it was stopped by customs in Lebanon,” she revealed. “They gave it back to us after a few months, and on each page they highlighted in red the word ‘America’ or ‘American,’ because you know America was the big enemy then.”

When I asked Salwa if censorship in Lebanon had diminished with time, she shook her head: “It’s increased.” We then spoke about the first ever photographic essay about cruising in Beirut, which was included in Transit Beirut, my second co-edited anthology, published by Saqi Books in 2004. As we were waiting for copies of the book to arrive from the Lebanese printers, many sleepless nights were spent worrying if Transit Beirut would be stopped at customs because the authorities also went through books leaving the country. But nothing happened.

The publishing house and the bookstore have long been champions of individual and non-normative voices. Saqi Books published three of my six co-edited anthologies. Since its inception, it has had a pivotal and pioneering role, bringing out works by authors such as: the Moroccan feminist Fatema Mernissi (1940–2015); the Tunisian academic/sociologist Abdelwahab Bouhdiba (1932–2020), who wrote Sexuality in Islam; and, more recently, the Palestinian journalist Elias Jahshan, editor of the anthology This Arab Is Queer.

Piracy, too, is a long-standing problem for Middle Eastern publishers, and it dogged popular Dar al Saqi titles as far afield as Cairo, a city known for producing cheap editions, and as nearby as London’s “Little Arabia.” When the bookshop found out that pirated Dar al Saqi books were being sold less than a mile away from the bookstore on Edgware Road, they contacted a lawyer. A threatening letter was sent; the books were removed. Outrageously, however, a week later they were back on the shelves. “The lawyer told us, ‘Listen to me: it will cost you more paying me than trying to remove the books,’” explained Salwa.

When other pirated editions of popular books in Arabic found their way into the bookstore, Salwa identified them from their thin, newsprint-like paper and “bizarre ink.” On principal, the bookstore wasn’t going to sell them, even when the original, legitimate edition had sold out, and people were clamoring to buy a pirated copy.

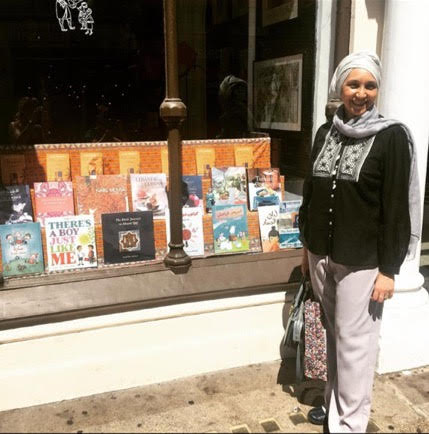

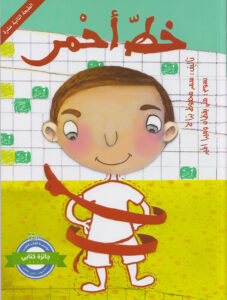

The iconic Al Saqi Bookshop on Westbourne Grove will be replaced by an interior design business. But Saqi Books and Dar al Saqi will continue. In March, Saqi Books will be publishing new novels by the Sudanese Scottish author Leila Aboulela and Kuwaiti writer Mai al-Nakib. One of the projects Salwa hopes Saqi Books will take on, under the continuing direction of her daughter Lynn Gaspard, is bilingual Arabic and English children’s books. Recently, Khat Ahmar (Red Line), a book that Dar al Saqi published in Beirut about teaching children to say no to sexual harassment, won a prize at a book fair. Dar al Saqi has another children’s book about having a handicapped sibling.

More Goodbyes

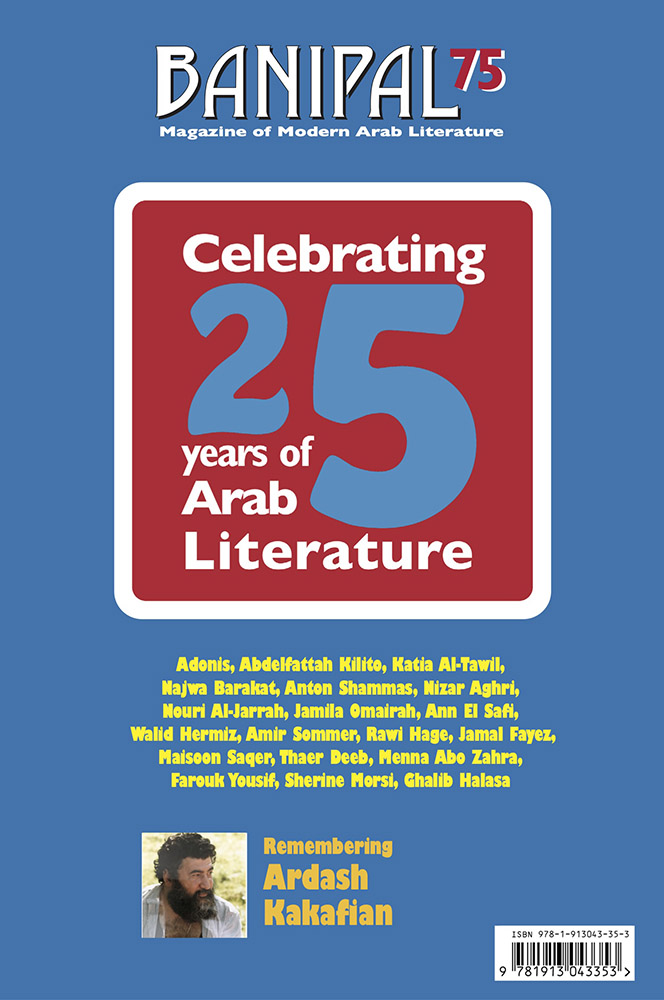

The bookstore’s farewell party was attended by longtime Saqi friends such as the famous musician and BDS activist Brian Eno. Also, there was Margaret Obank, co-founder and publisher of Banipal Magazine of Modern Arab Literature, which will also be closing this month after issue 75 and 25 years of publishing. Along with Saqi, Banipal has been instrumental in getting numerous Arab fiction writers and poets into English translation.

When asked about Banipal’s legacy, Obank related this story: “I was at a translation conference in Jordan and someone spoke from the British Library — maybe the keeper of Islamic manuscripts. It was in the days when they had projectors. He showed issue 10 of Banipal and said, ‘Arabic fiction in translation was a sorry state until 1998. It all changed with Banipal.’” Iraqi author and Banipal co-founder Samuel Shimon will still edit the magazine’s Spanish edition. The back issues of the magazine in English are available online and novels in translation will be published by its eponymous imprint. Banipal’s close association with the Sheikh Zayed Book Award for Literature, of Abu Dhabi, now in its 17th year, also continues.

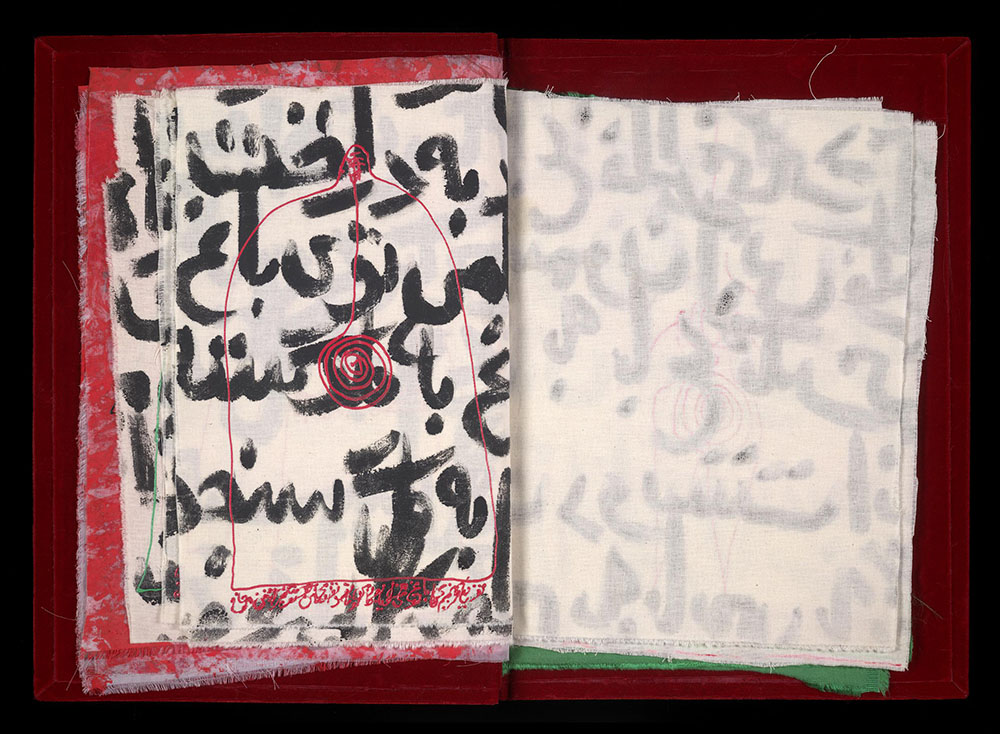

Also wishing Al Saqi Books a fond farewell was Dr. Venetia Porter, the British Museum’s Middle East curator, who stepped down from her post this past December. Since 1989, she has been instrumental in getting the museum to collect contemporary Middle Eastern art. Her efforts changed the thinking about such artwork: it was contemporary art in its own right, not part of Islamic art. There was a time when major Western museums and art institutions ignored new art from the MENA region. Now, that has changed for the better. Porter proved to be ahead of her time by weaving together the region’s aesthetics and lived experiences in her exhibitions and books. The artwork she collected for the British Museum was purchased by CaMMEA (Contemporary and Modern Middle Eastern Art) acquisitions group, which was founded at the initiative of the philanthropist Dounia Nadar. Porter will continue at the museum as a research fellow.

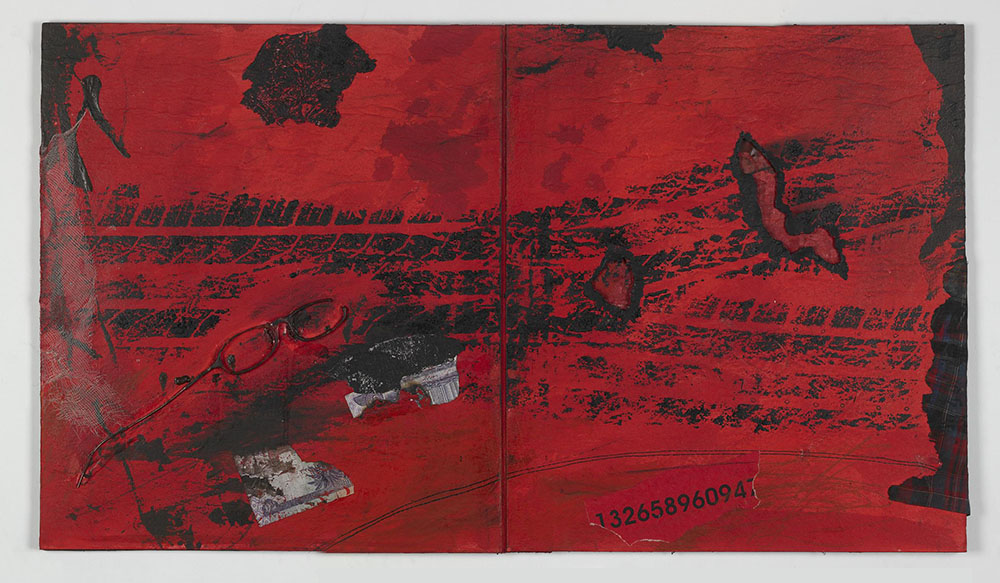

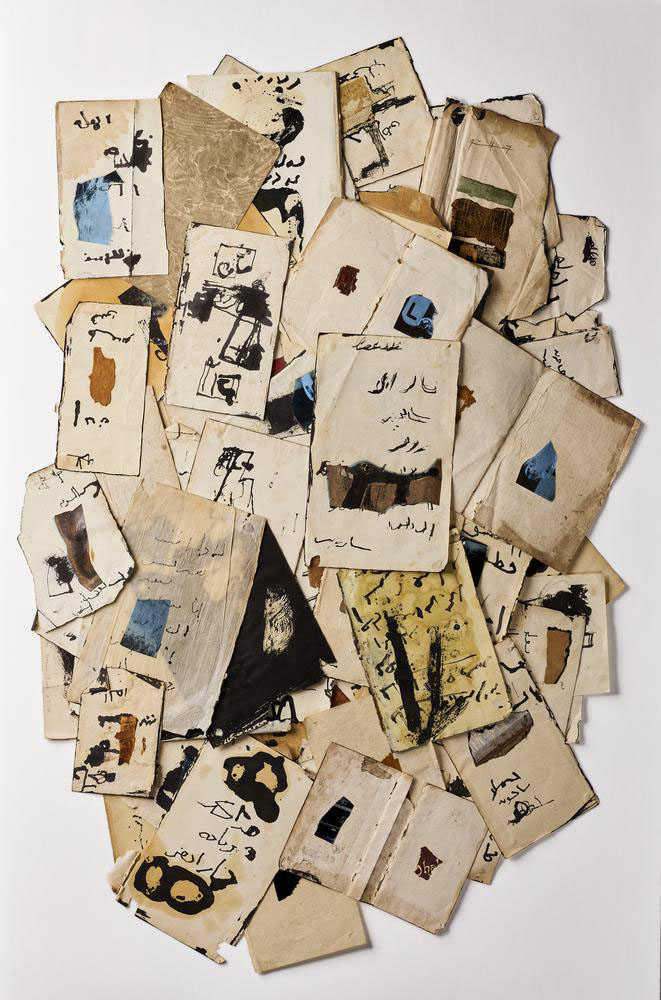

Porter’s most recent exhibition, in Room 43a, is “Artists Making Books: Poetry to Politics.” According to the British Museum’s website, the artwork on show is “made by artists from New York to Damascus and beyond,” and serves to “highlight the relationship between artists and poets and the influences that inform their work, from family to politics and everything in between: Lebanese artist Abed Al Kadiri (b. 1984) conceived his book during the first month of the pandemic to explore his family history, while through the eyes of Iraqi artist Kareem Risan (b. 1960) we see the shocking aftermath of a deadly explosion on the streets of Baghdad in 2005.”

Venetia Porter, Banipal’s Margaret Obank and Al Saqi Bookshop’s Salwa Gaspard have been pillars of Middle Eastern art and literature. The three, instrumental in establishing London as an important cultural hub for the region, influenced the way this creativity was disseminated and understood in the wider world.

For a younger generation, who are able to find the latest queer anthology in Arabic, English and French, or who can scour the British Museum website for a dissident Arab artist, there’s a tendency to think this is the way it’s always been. However, many of us will remember Edward Said and his comment when asked about Palestinian subject matter: you can find it but it’s on the periphery. In London, from 1979 to 2023, the periphery inched towards the mainstream, and produced a key change in the perception of the Middle East. Writing, art and ideas are the expression of many people, who should not be pigeonholed by the wars they endure and the elites or regimes who try to censor them. This approach and mission have made us listen more closely to new voices, and strengthened our resolve, and that of others, against social injustice. Now is the time for the next generation of trailblazing, cultural activists to step forward.

So Sad.