Ala Younis

“The smoke of war is blue

White are the bones of people”

–Du Fu

Sargon Boulous once said,

“These two lines are originally in Chinese, made of six characters. Du Fu wanted to put the whole history of humankind in them.”[1]

“The song of the rain

Rippled the silence of birds in the trees . . .

Drop, drop,

the rain Drip

Drop the rain”[2]

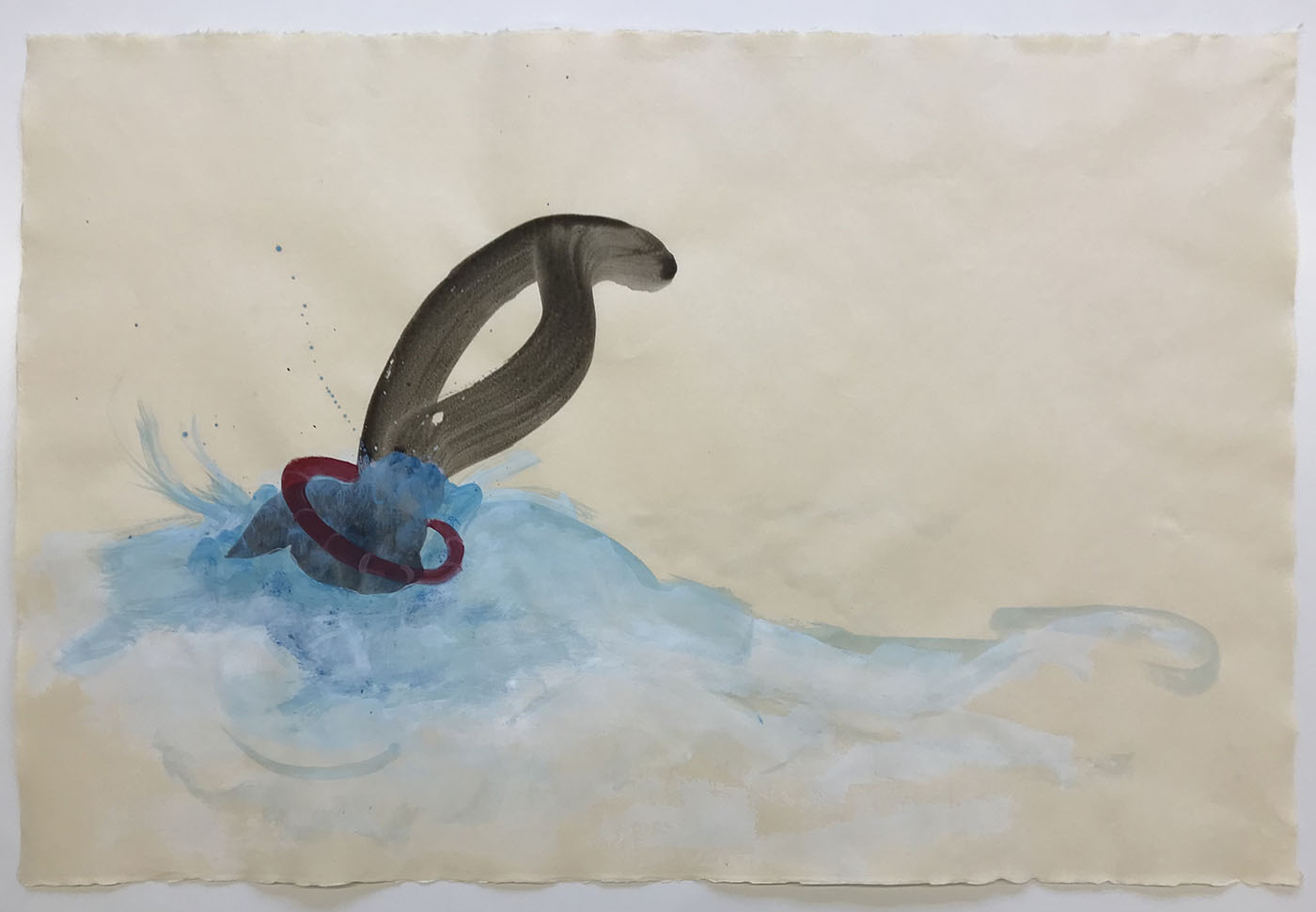

During the early latter half of 2021, Berlin-based artist Ali Yass spent a few weeks in a residency in Kunsthaus Essen, Germany.[3] There he worked on a series of paintings on canvas, many of which were inspired by the landscape that surrounded him in the Ruhr area. Throughout his residency, Ali jogged daily on certain routes until one day, people obstructed his way, telling him that the water had risen to the knees in the direction he was headed. On July 14 and 15, 2021, it rained so much that the Rheinland-Pfalz and Nordrhein-Westfalen were flooded, and soon severely damaged.

Upon hearing the expression of water rising to the knees, Ali remembered a war story from the Crusades: upon hearing that bloodshed had reached the knees, and in an attempt to gauge the gruesomeness of the bloodshed, questions were asked whether blood rose to the knights’ or their horses’ knees, as the latter would have been higher. This question of estimation and calculation, of probing memories of war upon thinking of (nature or any) violence, and of a human body and how it finds its resemblance in far more complicated setups and representations are the foundations of Ali Yass work. Triggered by these lines, Ali could see the floods through the eyes of his personal experience of displacement.

Ali trains his body to run, and thinks of the muscles that build up in this process. The thigh muscle is the largest in the human body, and its size and its build up through its function interest Ali and inspire his work. There is often a leg extended on its own, on the ground, in Ali’s works, to reference fatigue.

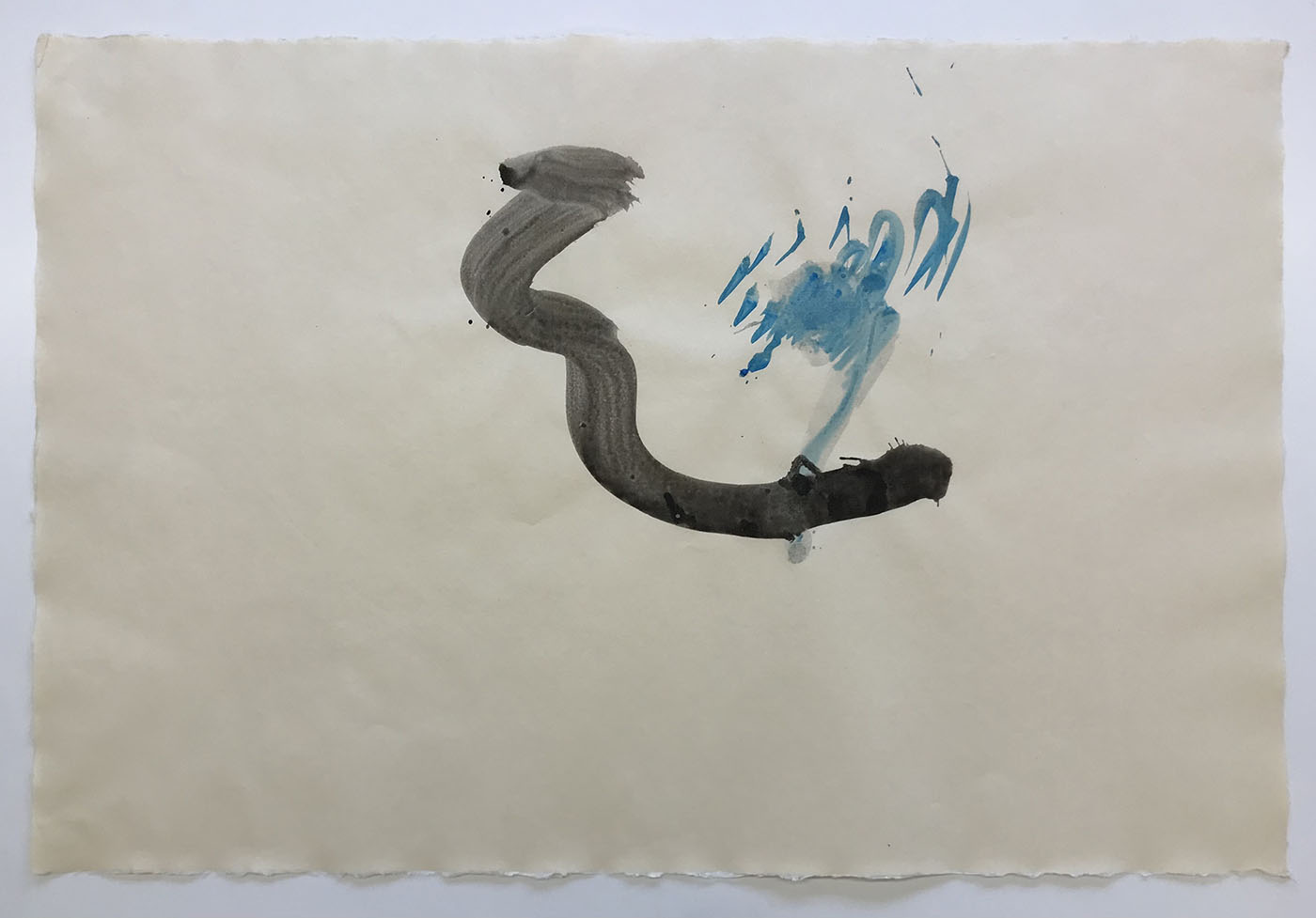

For his work “Die Flut” (The Flood), Ali chose a Japanese Washi paper that allows only what he calls a one-way ticket. A paper that allows a painting time that is short, swift, and possibly cautious, counter to the time allowed by painting on canvas, which can be long, changeable and multi-layered. In “Die Flut,” Ali applies a black stroke on the Japanese Misumi Kozo paper, using a big Japanese brush dipped in Chinese ink.

Ali says that he is not an abstract painter, and so a stroke on a piece of paper calls upon him to engage it with more thinking on the possibilities of drawing. Another stroke or other shapes start to crawl into the space of the painting based on what impressions the stroke made, not on its own, but also in relation to the intended series. Neither a stroke of black ink nor a developing painting on such paper can be altered or maneuvered, it has to be accepted, dealt with and built upon.

Some works take twelve seconds, others take many days.

In this series, Ali decides to leave one single work at the initial state of the stroke and perhaps an accompanying shape or two. He wants to leave it there, even in the status of an unfinished element — it is intentionally left there, to probe, activate, engage, contradict, evoke and converse with other lines and colorful shapes that will appear in the other pieces in this series. This seemingly unfinished abstract work can come to a completion later.

Ali was trained as a painter at the Faculty of Art and Design at the University of Jordan, where he was also a runner on the university team. Throughout his studies, he was taught to appreciate multiple steps of painting as they were practiced and evident in works by Iraqi masters such as Faeq Hassan (1914–1992), or the University of Jordan’s teachers who were trained under him, such the Palestinian Jordanian Aziz Amoura (1944–2018), who also taught on Faeq’s masterdom. Ali followed some of the steps until he met during his three and a half years of work at Dar al Anda Gallery, in Amman, the Japanese artist Norio Takaoka.

Ali is a person from Asia, but West Asia, from the Muslim world; he is from a place between two places, two times, two existences, at least. In Norio’s work and culture, Ali saw a simpler way to approach sculpture making, one that is based on meaningful repetitions and meanings of gestures, and that has roots in his memories from the old buildings and handcrafts in his Baghdad neighborhoods. Ali says, in Arabic or Japanese, he can say rose rose rose for a person to imagine one rose following another, yet it is difficult to imagine it this way if said in German. Ali studied German in Amman to speak it in Berlin, where he’s been based since 2017. Ali is now learning Japanese.

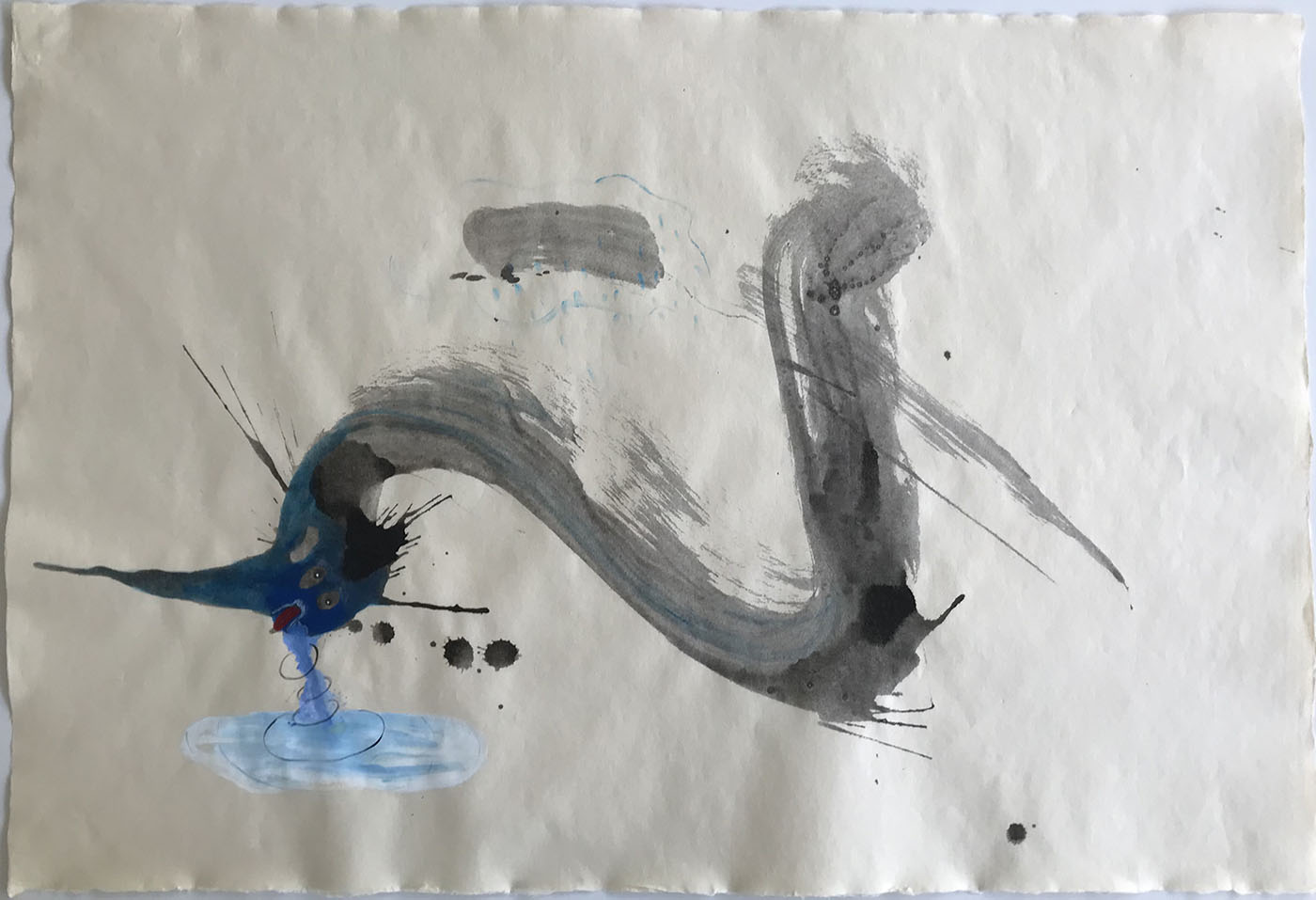

His painting practice activates Asian inks and brushes, in the mode of the Zen mind or brush, the art of black and white, of art made only with one brush, and art that is engulfed by a flow of forms, all bustling or dancing or fighting around one black stroke. His knowledge, world, and decisions travel with the speed of a thought, from the far east to where he is and was, until these forms start to speak. In the process of drawing, he identifies some shapes that could look like eyes, works them out until just before they become a painted eye, then he remembers the simplicity he learnt from the east, and pauses, “what do I want from the eye, what is the most essential in the painting of an eye? The glare! I worked on the glare detail in this eye. In Die Flut, I focused on movement of water, and in some works mud popped up. Besides black, blue was a main feature in many of the pieces, but each piece had its own logic and impressions on me.”[4] Just like Du Fu’s poem, characters or elements of storytelling here are brief but poignant; blue indicates a war but does not illustrate it, and body is the same wherever it is placed.

In Berlin, Ali works in sessions but has never moved his brushes between his studio and home. He starts by mapping the flow in the works using Chinese ink, studies their look, starts with the simplest and leaves the complex to later. It is like a casual Sunday run, he says, one starts with warming up, then jogging, then running in place. The artworks converse throughout the process, and creatures (human, animal, or other) start to appear in them. He does not work from sketches or prepared drawings and so the creatures pop up unexpectedly from impressions in forms he had just worked on. Ali uses the space of these paintings to reflect with himself on himself, the childhood he had in Baghdad, its fall and looting that he saw live during the US-led invasion and occupation of the city in 2003, and the journeys he had to take into the exile from 2008 onwards, starting at the age of 15 years old, and ending in Berlin.

These characters, or motifs, reference, respond and repeat around these traumas, desires, thoughts, and/or emotions in Ali’s life. The motifs have a status, not a life, because they are from the mind of the same person. Together they make sense, they reference a status or situation; a sitting or extended leg is a tired one, a running impression signals hard working, some blacks are eyes, others are beards or moustaches, and so on. In live drawing sessions at University of Jordan, Ali painted models from their knees downwards. The thigh appears as an obsession in his work, birds also appear, and some beasts, people with moustaches, his friends, including the Paris-based Iraqi artist Himat. These characters age, sometimes they retire, or leave the works and new characters come in their place. The characters are not fixed, they appear to tell a story, often stuck within the realm of the canvas, and they travel with Ali, to wherever he takes the canvas, home, university, metro.

“I feel I am stuck but not really, in certain phases, with these characters,” he says. “Also, that’s why I expanded my experiments to film, because they would allow a sphere for my drawings. I also see my personal resemblance, whether in the appearance of the legs or moustache, or the kid that sticks his tongue out to the world. In fact, sticking the tongue out is something I carried with me from my childhood in Baghdad, and that’s what I teach first to the children that don’t speak yet.”

In Baghdad, Ali Yass drove with his father to see how museums were being looted, by the occupation or contractors, or where not protected or let open, following the fall of the regime in 2003.

“I feel I am stuck at that moment that led to 2003, the war moment. Similar to a flood, people do not have time to rescue stuff and carry it outside of their flooding homes. When the war happened, I was 11 years old, nearly a teenager but also still a child. Everything I paint is linked to this moment that I feel I am looping with,” Ali says. “If I had not lived this moment, my work and my understanding of life and things would have been different. That momentum was my understanding of time and its pace, it was a pure momentum of anarchy or power vacuum.”

To further explain about the forms that we see in his works, Ali paraphrases his professor at Berlin University of the Arts (UdK), philosopher Alexander García Düttmann: “These creatures are post-disaster beings, or perhaps they are creatures that are about to encounter a disaster. They seem friendly or funny. I am not interested in retelling a moment but in understanding it and reconstructing it in relation to my current moment and what images and feelings I can recall from that moment. The occupation of Baghdad, I was not reborn on that day, but it is the year zero for me.”

These works are different from the series that was shown in 2019 at MoMA’s PS1 show, Theater of Operations: The Gulf Wars 1991–2011. “Those were the beginning of the project, I redrew the works that I made when I was a child, so these works were replicas,” explains Ali, who could not attend the show nor his objection presentation at the closing event. These replicas were hurt in the show when the museum refused to address the participants’ expressed concerns over having a head of the museum board with a background of earning from mercenary work in Iraq post 2003. For Ali’s voice to rise, he had to produce replicas of the replicas, turning them into originals. His forms had gone through fun times; remember, he experienced the war as a kid not an adult.

His work, as well as Berlin, constitute a place he now knows how to identify and how to come back to or enter; how to meet his characters. Combining a vital presence and activism in the city, by engaging in demonstrations, finding jobs and also studying at Berlin University of the Arts (UdK) for a Diploma, he has created the dynamism or the channels for the characters to come, and “so I am familiar with them, I know them. In MoMA, I had seen these characters only for the first time in context, but these are now more known to me, I know which meeting place I can see them in.”

In 2019, Kayfa ta (Maha Maamoun and Ala Younis) commissioned Ali Yass to produce two series, The Rainy Days and The Cloudy Days, for two shows on publishing organized at Warehouse421 in Abu Dhabi and at the MMAG Foundation in Amman. The accompanying text read,

“Six billion leaflets were dropped in Western Europe and 40 million leaflets dropped by the United States Army Air Forces over Japan in 1945 during World War II. One billion were used during the Korean War while 31 million have been used in the war against Iraq.”

“During the first days of the American invasion of Iraq in 2003, there was a huge sandstorm going on for days, which stopped the occupation army from moving towards Baghdad. As a kid, I was hoping for the rain to clear the air from dust but at the same time I was happy that the army could see nothing in such weather. Later, it rained; it rained so many leaflets.”[5]

Ali still remembers not only the huge sandstorm that delayed the advancement of the US troops, but also how he hoped for rainfall to clear the dust from the air, only to see it raining so many leaflets. He calls his project The Rainy Days, inspired by a poem by Iraqi poet Badr Shakir Al-Sayyab (1926–1964), who in the 1960s “shapeshifted” classical poetry structures and revolutionized the poetic and political writing of the time. But also, because, water features in this work when speaking about rain.

But the type of paper used in The Rainy Days series is different, it tolerates the multi-step elaborate painting processes in which Ali was trained. In this type of painting, Ali can delete parts of the work through layering, but this is much limited in the works he produced for Die Flut, which will premiere in the Singapore Biennale in October 2022.[6] In painting, he can go and come back, maneuver, but in the Die Flut series, it is only one act. That’s why, today, despite being painted in Berlin, this work relates to the moment of his childhood perhaps, where the first memories leave a clear and guiding mark on Ali and his understanding of life. In this series, this is Ali’s first time to work extensively on the same concept through both painting and drawings.

Ali does not refer to integration in Berlin but to making a choice of how to speak, which is a privileged position most of the time, upon understanding a context, its language and accents. He always asks on who has the right to the space, and reflects the body of a foreigner or an immigrant who has seen violence practiced by the landscape on his body; too cold, or too hot, too dark to accommodate, too white to tolerate, etc. He sees all of these aspects in his attempt, not to adapt to the place, and not to take it for granted. There is a possible space in between, there is the moment of collision that produces the energy of a place that can never be rendered in one light. At least it will always need two lights to paint a place.

In his class collective studio at UdK Berlin, with Hito Steyerl, Ali counted 33 brushes, seven of them Japanese, including the biggest brush, while some are Chinese, as is the ink.

Ali had not painted a palm tree since he left from Iraq. Only trees that he encounters in his present (German) space appear. What he is sure of, is that his color palette has changed from the almost monochrome he painted before coming to Berlin. “The colors here came out clearer and more vibrant. Riding on a bus in Jordan allowed me to see an open horizon as if I were floating. In Berlin, I only see trees very close to the windows of the train I take to my place. During my first months of arriving in Berlin, I always wondered why art students in Germany painted like Gerhard Richter, until I noticed fragments of his textures started to appear in my work! You will always be in the state of a moving object, like trains, you will always see blurred scenes. From Amman, many people (and creatures) surface in my current work, but not the place which I cannot reproduce but in what is available for me to shoot or capture. In film or moving images, I am always calling the current space to speak about that other place. I could talk about that moment of resistance in Baghdad, but I had to produce in a metro in Berlin. I have to find a way to change it to describe a place that I am not in anymore but have a story to reference. Sometimes, it can be an advantage to not have access to a particular place, so you have to reform and readapt your point of view towards the story, and try to make new associations according to your current possibilities. This will create a new momentum which bridging these two places, and connect these times together.”

The rain song tickled the silence of the sparrows on trees

Rain

Rain

Rain

The evening yawned and the clouds were still

Pouring their heavy tears

As if a child, before sleeping, was raving about his mother

A year ago, he woke up and did not find her

And when he kept asking about her

He was told

After tomorrow she will be back

She must come back

Yet his companions whisper that she is there[7]

In this article, I included two different translations of the same verses from a famous poem by Badr Shakir Al-Sayyab, published in 1962 under the title Rain Song. Being an outstanding and mature example of free verse style which Al-Sayyab and his peers experimented with from the mid 20th century in Baghdad. For this and also for its incorporation of myths, the poem was taught across different Arabic curricula for the past four decades. There is a difference between the two translations’ interpretation of the repetition of the word rain and its repetition across the poem, Rain Rain Rain, gives a feeling of a surrounding environment where many experience the pouring rain, while Drop Drop Drip is a particular sound or image as if observed by one person. This combination of two positions, besides the example of rose rose rose given by Ali, can illustrate to us the way how a choice of paper, lines, creatures, or songs on rain can also be as autobiographical as attempting to make these choices in Berlin, where he is now preparing for his first marathon there.

Endnotes

[1] From a recording by Iraqi poet Sargoun Boulous (1944–2007) introducing then reciting his poem, Du Fu in Exile. Accessed on 6 September 2022 at https://youtu.be/V7UGRPH06EM

[2] Translation of Rain Song, poem by Iraqi poet Badr Shakir Al-Sayyab, translated from Arabic by Lena Jayyusi and Christopher Middleton. Accessed on 8 September 2022 at https://www.poemhunter.com/poem/rain-song-7/

[3] DAS KHE RESIDENCE-PROGRAMM 2021, Kunsthaus Essen, an interview with the artist during the residency is published at this link https://youtu.be/pFwcikJDCUA

[4] Interview with Ali Yass on 28 August 2022.

[5] Ali Yass, The Rainy Days”, How to maneuver: Shapeshifting texts and other publishing tactics, eds. Maha Maamoun and Ala Younis, published by Kayfa ta and Warehouse421, Abu Dhabi / Beirut, 2020, 235.

[6] Co-curated by Ala Younis, Binna Choi, June Yap and Nida Ghouse.

[7] THE RAIN SONG by Badr Shakir Al-Sayyab translated from Arabic by Khaloud Al-Muttalibi. Published in Knot Magazine in Badr Shakir Al-Sayyab, FALL ISSUE: 2012. Accessed on 8 September 2022 at this link: https://middleeasternliteraturejournal.wordpress.com/2012/09/09/the-rain-song-by-badr-shakir-al-sayyab-translated-from-arabic-by-khaloud-al-muttalib/