Select Other Languages French.

Starving a captive population, for centuries a legitimate war tactic, became unacceptable after the First World War, when “deliberate starvation of civilians” was considered a violation of war and subject to criminal prosecution. Today, international law defines the intentional withholding of food from a civilian populace during armed conflict as a war crime.

What happens when a child stops crying from hunger — because there’s no strength left to cry? When the body begins to shut down, organ by organ, and the damage becomes irreversible?* In Gaza, famine isn’t a warning. It’s already written on children’s skin, in their brittle hair and emaciated bodies. Clear in the very streets.

Gaza’s hot. Too hot. Gaza smells like something that’s been left out too long. The stench — sewage, sweat, something else you can’t name — catches in your throat. It hits before you even see it. You swallow it without meaning to. It stays in your mouth.

Outside Amin al-Mansi School in Gaza City, where families take shelter in war-damaged classrooms, a dirty stream creeps through the sand where children once played. Flies cling to stagnant sewage pools. Kids lay around, not talking, just staring. No games. A little boy in a corner draws in the dirt. It looks like a plate. Or maybe it’s only a circle. He doesn’t finish it. Just lets his hand drop.

Inside it’s worse. No air, no quiet, just this thick, sticky heat. The kind that makes your skin itch. There’s no electricity. No privacy. No safety. A girl sleeps near a classroom door. Or maybe she’s not sleeping. A fly lands on her face and stays there. No movement. Her sister curls up next to a wall, facing away. Nobody talks. Nobody stirs. It’s too hot. Too quiet. You wait for a child to cry, but they don’t.

The hush in the school isn’t rest, it’s raw fatigue. The walls are blank. No chalk smears. No faded student drawings. No posters. Nothing but bare concrete and a stale echo of the life that once was.

In the back of one classroom, Lina Abu al‑Kas, 28, sheltering at the school with her six children, props herself against the wall. Her son Majed droops over her shoulder, limp and exhausted. “He hasn’t eaten since yesterday,” Lina whispers, her voice cracking. “Even his dreams… they’re about food.” Nearby, her other children lie still, conserving what little strength they have left.

Lina’s family has been displaced more than 20 times since October 2023 — fleeing from the Shujaiya quarter of Gaza City to the streets, from the homes of relatives to this cramped classroom where they now live with three other families. “We’ve been here since last August,” she adds. “The children have never known peace. Their entire life is displacement.”

Her children — Haneen, 11; Hiba, 8; Majd, 7; Jude, 5; Ne’ma, 4; and Amal, just 2 — have adapted to a life where normalcy is hunger. Meals, when they come, are made from scraps. “If I manage to get a kilo of rice — 100 shekels ($29) now — I divide it into two meals. Sometimes lentils, sometimes pasta that we convert with water into dough for a little bread. No oil, no salt. Just enough to trick the stomach. They drink water and sleep hungry. We haven’t seen fruit or vegetables in months. Amal doesn’t even know what a banana is.”

The children whisper together. “I want chicken. I want to sleep in my own bed,” Jude mumbles.

“When I’m hungry, I drink a lot of water and go to bed.” Majd dreams of maqlouba.

But even water has to be bought from vendors who haul it through the streets in donkey carts or sell it by the tank.

Their father, Abu Majed, once worked in construction. Now he sits in silence. “Fridays used to mean fish or chicken,” he recalls. “Now, I can’t afford a biscuit.” He looks down. “My heart breaks when I come home with nothing.”

My daughters grew up too fast. Hunger forced them to.”

In northern Gaza, Mohammed Al-Halabi faces similar despair. In his cramped shelter, the single room that remains of his family’s damaged home, he watches his daughters fade. Rama, 13, once energetic, is now unrecognizable. “She lost weight so fast, it’s terrifying,” he says. Rose, only 5, suffers constant pain. “She always says something hurts — her legs, her head, her stomach. She gets dizzy. Tired. And there’s nothing I can do for her.”

Before the war, they ate like any other children. “Meat. Fruit. Sweets,” Mohammed recalls. “Now it’s one meal a day. Mostly lentils. Sometimes rice. Maybe pasta. No oil, no vegetables, no sauce. We eat bread when we can find flour. That’s all.” He used to rely on a few savings, but that’s long gone. Now, he buys a one kilo of flour at a time when he can, making dough to bake in a community oven. A single pita loaf is torn in two: one half for each daughter.

In parts of Gaza, limited internet still flickers through the ruins — sometimes through a solar-powered router, sometimes for only a few minutes a day. In one neighborhood it works, in another it doesn’t. The connection is as fragile and fractured as the lives it reaches, offering children fleeting glimpses of a world they’re locked out of. When Rose asks for something, Mohammed braces himself. “She’ll say, ‘Baba, I saw chocolate in a post on the phone.’ But she says this knowing I can’t get it. They don’t cry for food anymore. They understand.”

He says hunger has made them older than they should be. “Your child asks for something simple, a piece of chocolate, and you know it’s available, but impossible to buy,” he says. “Sugar costs 570 shekels ($170), cocoa 180 ($54). Even if it’s there in the market, it’s beyond reach.”

Mohammed has resorted to creative substitutes, making cakes, biscuits, even coffee with ground lentils. “But substitutes don’t stop hunger from harming their bodies,” he says.

Rose’s weight fell below 12 kilos. Doctors diagnosed a bacterial infection from contaminated shelters. Treatment helped briefly, but her weight still fluctuates dangerously. “She needs special supplements, therapeutic food,” Mohammed explains. “But it’s not here. It doesn’t exist anymore.”

Her body is fighting something bigger than bacteria: starvation. “All I want is for one day in which my children don’t go to bed hungry,” says Mohammed. “Just one full meal. That’s all.”

Hunger in Gaza is not a byproduct of war. It is a deliberate weapon. Since March 3, 2025, Israel has blocked all aid crossings — no food, no water, no medicine. By June 20, the UN World Food Program confirmed that all 2.1 million Palestinians in Gaza are facing acute hunger. At the time, at least 70,000 children required life-saving therapeutic food. By late July 2025, at least 80 children were confirmed to have died of starvation, up from 52 child hunger deaths in April — a 54% increase in under three months.

This has been a calculated progression by the Israelis. In late May, screenings conducted by humanitarian groups had already found 5.8% of nearly 50,000 children in Gaza suffering from wasting, a form of acute malnutrition that can kill without treatment. A Reuters review of UN data confirmed that child malnutrition had nearly tripled since the ceasefire in February. That same month, at least 29 children and elderly people died from starvation-related causes.

By March, the UN-backed Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) reported that nearly half a million Palestinians — one in five — had entered Phase 5: Catastrophe, the highest possible classification for food insecurity. It is now three months later, and things are only more catastrophic.

Most families have no income, no work, no savings. Families survive entirely on aid. But even aid has become a gamble with one’s life, as Israel took over the administration of aid from internationally-recognized NGOs and turned aid sites into killing fields. Israeli troops have shot and killed hundreds of aid seekers, while gangs, likely armed by Israel, steal food and re-sell it for outrageous prices.

And while the bombs still fall, parents watch their children wither. Lina’s daughter, Amal, just two years old, holds a piece of bread like it’s a doll. Lina’s older daughter Ne’ma, 4, is showing clear signs of starvation. “She’s pale, she gets dizzy, she’s smaller than she should be at four,” explains Lina. “But medical help is hard to get… All I want is one day they can feel full.” She brushes the hair from Amal’s eyes. “I just want one day where they don’t sleep hungry. I want to go home. I want to make maftoul (Palestinian couscous) and plant flowers on the balcony. I want to hear them laugh again.”

* According to Dr. Fadi Bora, discussing the situation in Gaza today, “Medically, a person who has entered an advanced stage of starvation cannot be saved by food and water alone. Without specialized medical care, death awaits nearby even if they’re suddenly offered lavish meals. This is a body whose systems have collapsed, whose muscles have disintegrated, whose organs have shrunk, and who has become nothing more than a moving skeleton. Tens of thousands of our devastated people may have already entered this final stage of starvation …They are likely to leave this cruel world very soon. And yes…most of them are children.”

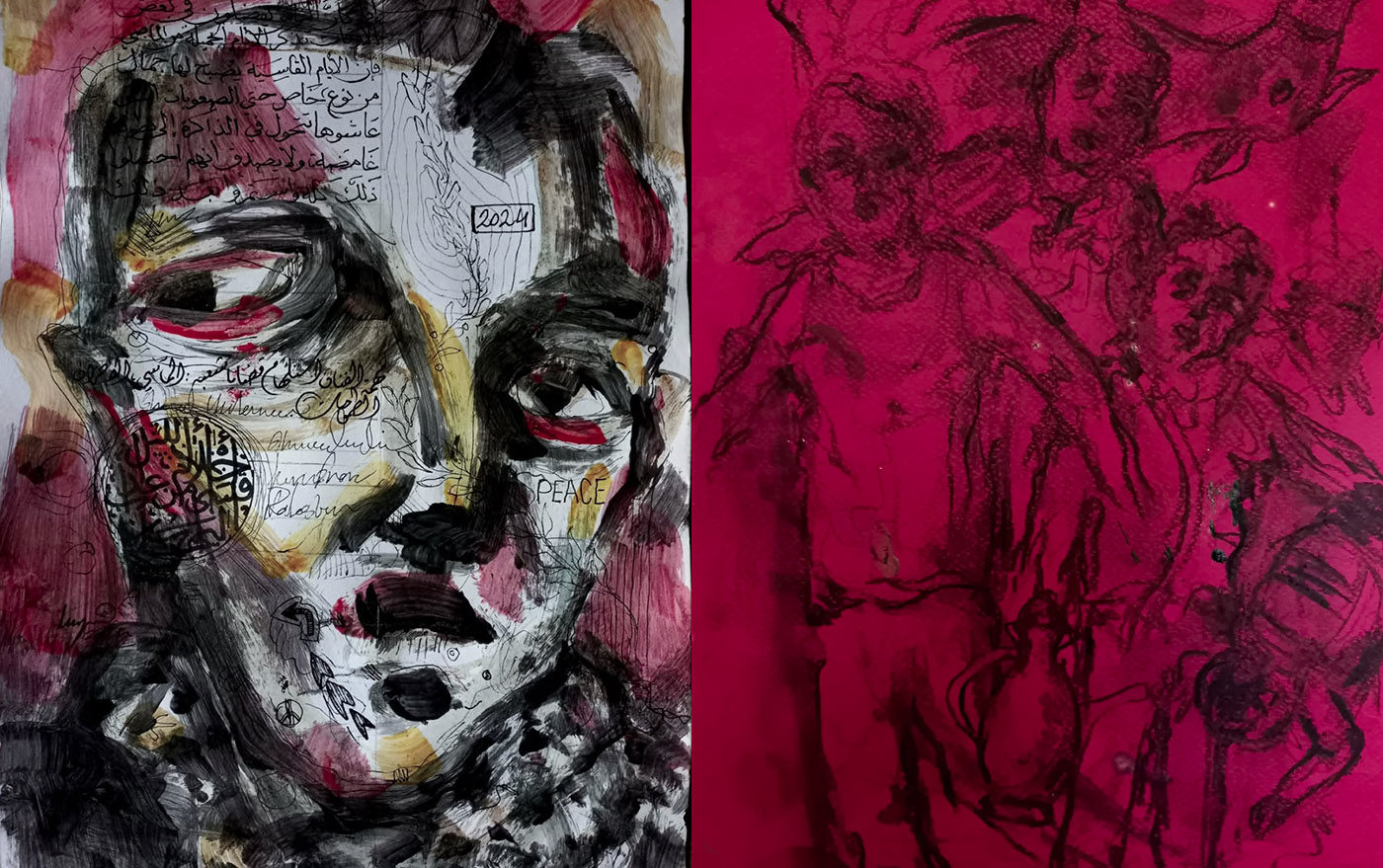

![Fady Joudah’s <em>[…]</em> Dares Us to Listen to Palestinian Words—and Silences](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/SAMAH-SHIHADI-DAIR-AL-QASSI-charcoal-on-paper-100x60-cm-2023-courtesy-Tabari-Artspace-300x180.jpg)