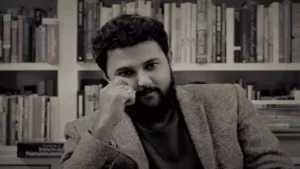

Arie Amaya-Akkermans

Is a chronology possible in poetry? Does one read an author’s work beginning with the first poems and then passing through the middle before reaching his or her final poems? What exactly is there in the middle and where does their poetry end? And what do we mean by a final poem?

With the departure of Etel Adnan (1925 — 2021) last weekend, perhaps the greatest Lebanese poet of her generation, and a contemporary painter of renown in her own country for decades, (her recognition by the international art circuit arrived late, when her work was discovered by Caroline Christov-Bakargiev and exhibited at Documenta in 2012; by then she was 87 years old), we become confronted with the terrible truth that she had in fact forewarned us of her last stanzas.

In October 2020, in conversation with Hans Ulrich Obrist, she spoke clearly: “My last book is about realizing that I am going to die. It’s different to know and to feel it, and it’s as if life happens in silence. There is behind the noise of daily life a silence that we hear, another noise, a shifting silence. This silence has changed the focus of consciousness. That’s my last book.” It’s a modest book, aphoristic, sparse, and slow.

The book was published in September 2020, and it’s titled Shifting the Silence, for many a familiar elegy to the confinement, then somewhat new but now ubiquitous and ever returning to our lives in the pandemic present-at-large:

“Yes. The shifting, after the return of the tide, and my own. A question rushes out of the stillness, and then advances an inch at a time: has this day ever been before, or has it risen from the shallows, from a line, a sound?”

Endless rows of days that look ever the same, and that move in no specific direction, in a kind of really tedious, overextended, fluctuating eternity. Yet, these fragments of experienced time, coexist with the untimely meditations (to paraphrase Nietzsche) of a then 95-year-old poet, weary from the ceaseless collapse of historical time:

“I am wearing the rose color of Syria’s mountains and I wonder why it makes me restless. Often my body feels close to sea creatures, sticky, slimy, unpredictable, more ephemeral than need be. From there I have to proceed, as an avalanche of snow falls. That’s what the radio has just said: that entire villages have been made invisible. But they are faraway: the news never covers my immediate environment.”

For someone who lived almost through an entire century, from the creation of Lebanon and the tragedy of Palestine to the pandemic, passing through both the Vietnam War as an American poet and the Lebanese Civil War as a not so silent witness, confinement wasn’t new. In “To be in a Time of War,” published in 2005, you find what it feels like a reflection on Beirut in the 1970s, but also in the 1980s, but also in the 1990s, but also today and ever. It is a reflection on the helplessness of sitting at home and waiting for it all to end:

“To say nothing, do nothing, mark time, to bend, to straighten up, to blame oneself, to stand, to go toward the window, to change one’s mind in the process, to return to one’s chair, to stand again, to go to the bathroom, to close the door, to go to the kitchen, to not eat not drink, to return to the table, to be bored, to take a few steps on the rug, to come closer to the chimney, to look at it, to find it dull, to turn left until the main door, to come back to the room, to hesitate, to go on, just a bit, a trifle, to stop, to pull the right side of the curtain, then the other side, to stare at the wall.”

And so on. The poem goes on for an entire twelve pages, replete of possible actions that can be entertained while waiting. You can feel here the acid despair of poetic microphysics: Etel Adnan, like Paul Celan, has completely stripped language of adornment. This language can now wound you and leave cuts. There’s no space to breathe. And then it is followed by an agonizing silence.

That is how I turned to this poem to help me think through Agenda 1979, (in an essay written for this publication), the experimental opera by Gregory Buchakjian and Valerie Cachard about a warfare manual by a Palestinian fighter found in an abandoned apartment in Beirut. When you’re faced with the unspeakable, you need to speak in silent signs.

But speaking about silence, and how to shift it, was for Etel Adnan, the thinker and poet of Beirut and Paris, of Sauzalito and Erquy, something much larger than a meditation about finality or the license for poetic silence that follows from the end. This is because the ends are endless; the end of life, the end of war, the end of love, but also, sometimes, the happy end of suffering. Silence in Etel the poet, is the fundamental unit of thinking, and the way in which thought attempts to translate itself into the inner voice. For Etel, the painter, painting was the attempt to break through the silence that words create around us.

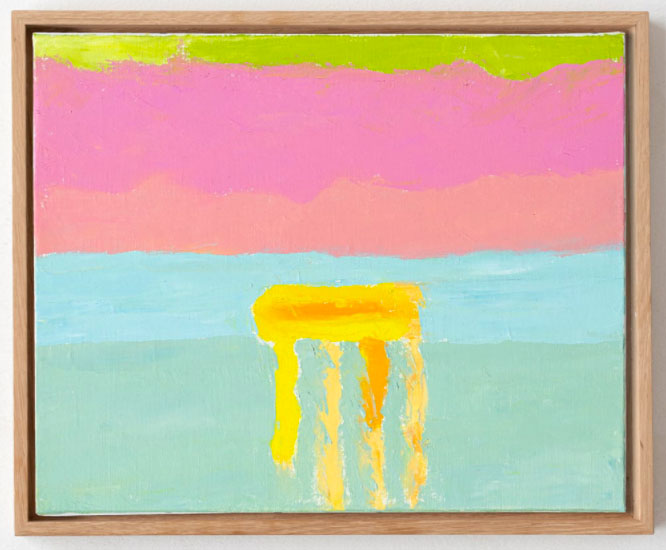

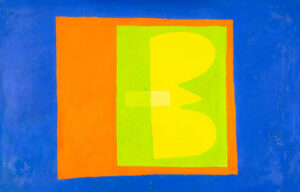

In a recent painting, “Horizon I,” executed through the pandemic in Paris, you can see how the waves of the sea, circles of astral bodies and the squared-shaped color fields, associated with her painting, give way to soft, pastel, horizontal lines, pointing indeed at a shift in direction. But these horizontal lines speak of interminability, rather than of finality, which one will have to search for elsewhere (geometric lines and stasis can be found also elsewhere in her painting).

Etel Adnan began painting in 1959, at the age of 34, while teaching the philosophy of art at Dominican College in San Rafael, California (she had studied philosophy at Berkeley and Harvard). As a self-taught artist, Etel’s style did not really belong to any schools and was intimately bound with her particular sense of observation, her thought trains and of course, her poetry. And how could Etel Adnan belong anyway? Born in Beirut to a Syrian military officer and a Greek woman from Smyrna (the present-day Izmir in Turkey), who fled to Lebanon after the Great Fire of Smyrna that brought the Greek presence in Anatolia to an end, Smyrna would remain one of Etel’s obsessions, even though she never visited it:

“Izmir was like a lost paradise at home. We would cry when we mentioned the city. When I saw huge clouds on the horizon as a child, I would ask, ‘Is this Izmir?’ And whenever I went to the beach in Beirut to swim, I would say, ‘I am going to Izmir.’”

In 2016, Lebanese artists and filmmakers Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige, released their film Smyrna, entirely based on their journey to Izmir, where they were meant to travel with Etel, to interrogate their attachment to an imaginary Smyrna, since both Joana and Etel shared roots among the Greeks of the Ottoman Empire who fled to Lebanon after the catastrophe. Eventually, they would travel without Etel who could no longer travel by plane, and the bulk of the film is the conversation between Hadjithomas and Adnan, recounting their memories; truth, fiction, parafiction, the lines are blurred. “The only thing that remains is oral transmission, so recounting for us practically meant surviving,” says Etel to Joana in the film, as they examine videos and photographs of the real Izmir, juxtaposed to the imagined Smyrna.

Recently, Hadjithomas told Karina El Helou and me in an interview about the intersection between their work and poetry, and specifically the experience of working with Etel Adnan on the film: “In many of our projects, Khalil and me, we like to work with others, to collaborate, or to borrow the eyes, the words of others, the knowledge, whether it is from archaeologists, journalists or geologists, or poets. In this case, for poetry, the poems that we recall, are the center of those works, like the poem of Cavafy, or the one of Seferis, but also the presence of Etel, it’s something beyond, she’s the poetry herself. Her presence was pure poetry all the time.”

In the dialogues in the film, as in different interviews of the artist and poet, it’s difficult to distinguish the boundary between Etel Adnan’s poetry and memories and philosophical thoughts and everyday reflections. They have merged into one whole. Therefore, the question of the beginning or end of poetry, or of a poet’s work, seems rather immaterial here, because temporality is in Etel Adnan not points in a straight line, but a dispersion, in the same way that her spatial geography was. In a dialogue with author Andy Fitch, discussing the ineffable aspects of poetry and thinking, she spoke of her concept of time:

“Often we feel time to be linear, inexorable, suffocating. At other moments we find it oceanic. We kind of swim in it. We expect physicists to come up with an explanation, but we don’t find one, and come back to our intuitive use of the concept. But there are also moments when time appears to be, to say it in one way, both vertical and horizontal, both ‘single-minded’, monotonous, inalterable, and multi-dimensional, infinite.”

Is this poetry or thought or speech of reflection? Etel proposes an answer: “It seems to me that we are porous material: There’s a double trajectory of the world to us and from us to the world, because ultimately we are part of each other.”

In these transitions and translations between the image and the word, I often wondered whether it is possible to have seen a poem before you read it or to have read a painting before you’ve seen it? I don’t have an answer from Etel, but I think that she revisited this idea often when discussing her paintings of Mount Tamalpais in California, and it brings me back to a painting of Mount Sannine in Lebanon by her partner Simone Fattal, about which I learnt from Buchakjian and Cachard (it was one crucial battlefield in the Lebanese Civil War). I’ve never seen this painting, but a stanza from Etel in her last book, made me feel as if I had:

“We have lost the liturgies under the wars, the bombings, the fires we went through. Some of us didn’t survive, and they were many. The Greeks had their exuberant gods, the sunrise over Mount Olympus. The Canaanites had Mount Sannin. We have our own private mountains, but are they already too tired from waiting for us? I have no roads to them, no wires. In their splendor let them be.”

Now I have a personal recollection of seeing a poem before reading it: It was an early evening in August when I first saw the red sunsets of Antioch, from the bay of the ancient Seleucia Pieria, in Samandağ, a few kilometers away from the tip of the Orontes River, the border between Syria and the southernmost tip of Turkey. I traveled there by motorbike with Barış, conquering the steep hills and plateaus of a mountain range that extends all the way into Lebanon, hiding the shoreline from prying eyes. We always spoke about these blood red sunsets as the wine-dark sea of Homer, and imagined a lost Achilles traveling down south from Troy. This experience of sun and sea, so absolutely physical, after nearly two years of pandemic confinements, was exhilarating and reminded me of Etel’s thoughts about the sea in ‘Sea and Fog’:

“The sea is not having nightmares about the Milky Way. Coppery clouds descend through a passage down the coast. The hills loom in a steely blue color that can slay the heart by its beauty.

We’re spending a life loving it exclusively because we couldn’t change the world. Blinded by its light, our retinas rest on its epidermis, follow its ripples. Its assaults are mercurial, its nights, impenetrable. Voices speak of a species which is wounded. Space is not some abstract notion but our own dimension.”

And then, Etel on Achilles, in the same poem:

“The sea ignores Achilles’ death and can’t be warned, as we have forgotten her

Alphabet. Space narrows down to a slit: radiation reaches the brain, burns neurons.

Sliding into deep sleep, the brain erases all, cancels itself.

In an invented summer, the world breaks apart. Slowly mountains appear…

Through a multitude of traps set by divinities. Are these beings still among us?

Sometimes they are.”

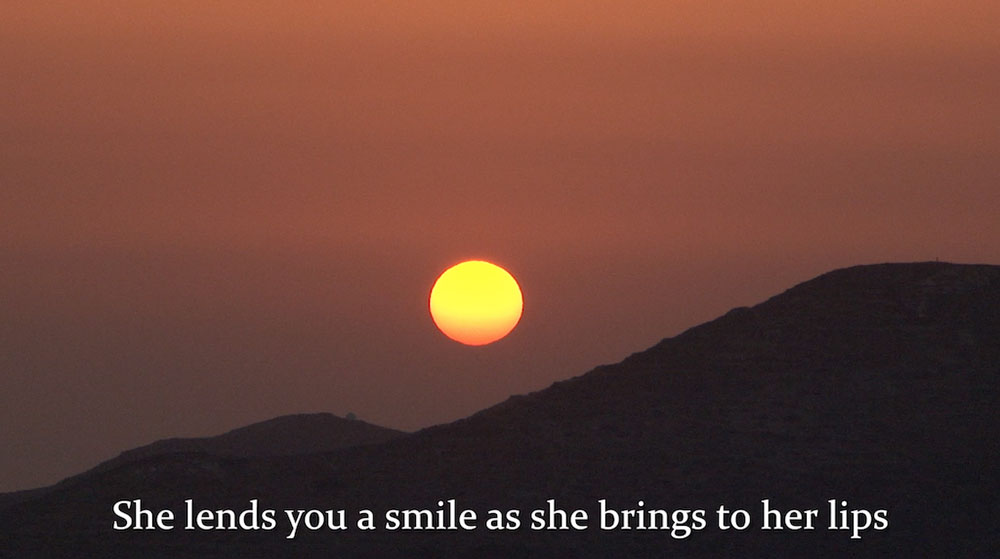

Upon returning to Istanbul, my first encounter with “Sun and Sea”: It was the first poem that Etel Adnan wrote in 1949, at the age of 24, in French. Another Lebanese artist and filmmaker, Lamia Joreige, had wanted to set this poem to video in 2011, following the instructions of Etel: The video should be shot entirely in Greece, and the artist needs to have read works by Nietzsche (Etel Adnan said that reading the poem 60 years later, it seemed to her that there was connection between Nietzsche and the poem in some way). Joreige didn’t complete the project, thinking about how it would be possible to create a tale of beauty and serenity while everything was going so badly in Lebanon, Syria and Palestine?

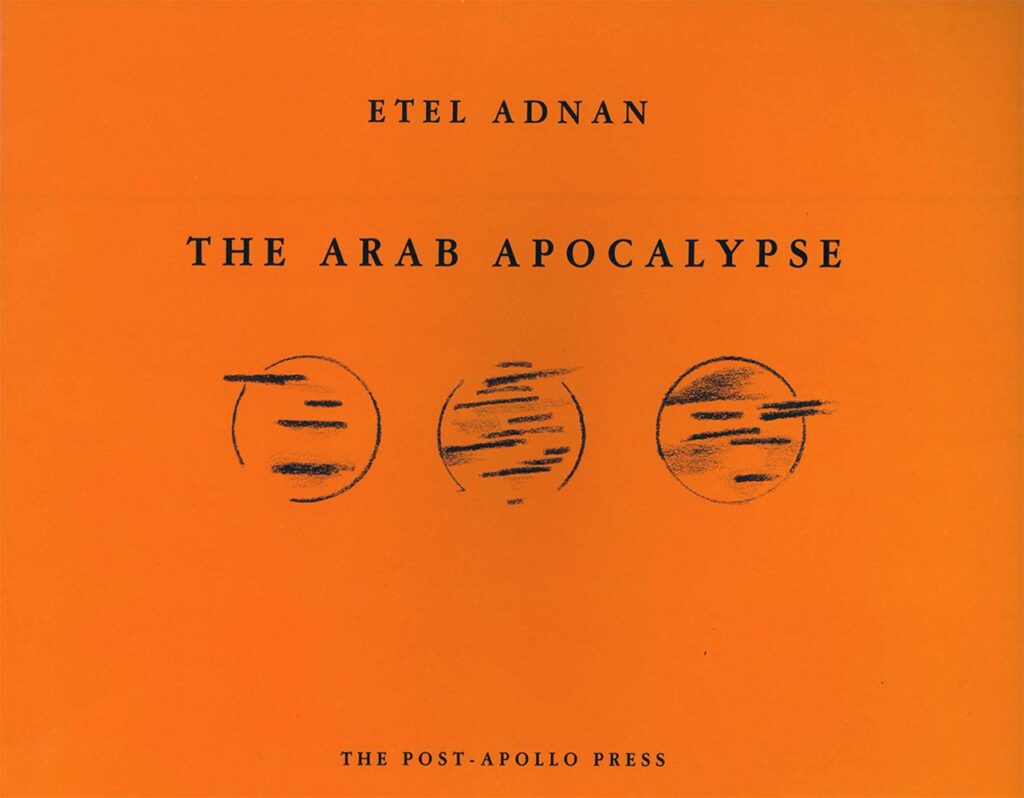

In 2021, she revived and completed the project upon an invitation by Karina El Helou to take part in an exhibition in Istanbul around the topic of the sun, connected to Etel’s most famous work, The Arab Apocalypse. The exhibition included works by both Etel Adnan and Simone Fattal, as well as Gregory Buchakjian, among others.

The Arab Apocalypse was written at the height of the Lebanese Civil War, after the siege and subsequent massacre in the Palestinian camp of Tel al Za’atar. Etel called it her harshest poem, an apocalypse of the sun, a sun that has swallowed Beirut:

“In the sky a solitary coffin is floating from one horizon to the other

A horse with lanterns for eyes carries the body in his mouth, rainbows are perfect

A militant sky aims its Kalachnikov at the heart. BANG”

“Sun and Sea,” in contrast, is nothing like an elegy:

“I would like to speak to you of the sea, of its patience. Of the sun entangled with her. To tell you of the brass deafened by the waters.”

It is a lyrical song, telling the story of the sun and the sea as mythological creatures. That this poem was written so early, contradicts reception of her poetry as either minimalist or postmodern, because here she already introduces many of the topics and styles that would characterize her poetic signature through the years:

“O sea, do I need to know you’re deep when your surface alone dismays,

to know you pacified, when your lips are eternal machines,

to know you sacred, you woman, adulterous woman, violated woman…”

Nature and the astral bodies are prominent in this poem and eponymous video by Lamia Joreige, as Etel herself reads the poem, sometimes alone, sometimes doubled up by Joreige, laid out against the mesmerizing images of the shores and the islands and the rocky hills of Greece. Etel Adnan’s immense love for the sea foams up already in the first lines:

“With what clear memory we remember the sea!

The sun says: Sea is the original life, I am the future

Vines and the panther’s verve.

The sea is a woman on the lap of dawn.”

In a short conversation between both artists at the beginning of the video, Etel introduces her lyrical fixation with Greece that will reappear throughout her poetry in the form of classical mythology: “I have the feeling that Greece is a place that liberates you from yourself.”

In the poem she refers to ancient deities as personifications of both sun and sea,

“She says:

You, sun, Ra, Marduk, once my father now my

lover, make me return inside your eye and your matter, make

me rise into your realm, or else go down into my depths.”

The two mythical figures, the astral body and the expanse of waters, both sources of life, are engaged here in a titanomachy:

“You are a dwarf, says the sea, compared to the other stars.

Don’t lose sight of my omnipotence, says the sun. My kiss

applied to your entire surface will be the awaited cataclysm.”

And the most striking passage, at the very end:

“I saw the sea in the cell and the cell in the middle of the sea.

I saw the sea in the sun and the sun in the middle of the sea.

I saw the sea in your eye and your eye in the middle of the sea.”

Who could possibly not get lost in love in those words?

After that journey between Antioch and the mountains and the sea, culminating in the blood red sunsets of Samandağ, one is always left with the feeling that he has read Etel’s poem before, that he has always known it. And in fact, this is true for all of Etel Adnan. If you’ve seen Sannine or Tamalpais, you’ve read all of Etel Adnan, and if you’ve read all of Etel Adnan, you’ve seen Sannine and Tamalpais, and Beirut, and you have ascended into love, or descended into war, and cold death. So is it perhaps the case that the first poem of Etel Adnan was already her final poem, even when it wasn’t her last, or anywhere in the middle?

There’s a scintillating moment of philosophical maturity in the last stanza of the poem, that would be reflected in her conversations throughout the next six decades, and that explains her affinity for Nietzsche:

“Multiple and one, one and the other apart at the same time, their image equal, one in the other, yet also reduced and rounded, now together they know through eroticism and through innocence, there is no duality nor unity, but the multiple always one, that begins at dawn, and begins again at dusk.”

This is already a message from beyond: No beginnings or ends, in life or in death.

In her final book, she refers back for a last time to the gods of Greece:

“I miss the cosmic energy of ancient Greece. They loved their gods to whom everything was given save the supreme power. Free, none of them were in the absolute sense, only Zeus was, though his arbitrariness was often looked at with a critical eye. Prometheus was chained because he rebelled, and Io was condemned to suffer an opposite but equally radical punishment, to turn and turn and never rest. There was a raw cruelty to their world, but I miss them, just the same.”

It would be foolish to read this as a farewell, but rather, we should read it as a turn towards sempiternal time, towards the horizon of infinity. She explains her love for the sea and for Nietzsche in these terms, during her conversation with Fitch: “Addiction to the sea, addiction to Nietzsche: we come back to them for the same reasons, I am sure. They are infinite, not a narration to be understood once and for all, but a recurring source of amazement.” So it is for us with her poetry.

Much has been written and said about Etel Adnan since her death last week, testament to her stature, from her famous novel Sitt Marie Rose, to The Arab Apocalypse (still considered a major success for an experimental work), countless museum exhibitions and the most famous queer relationship among intellectuals in the Arab world, that of Etel Adnan with the sculptor, painter and philosopher Simone Fattal.

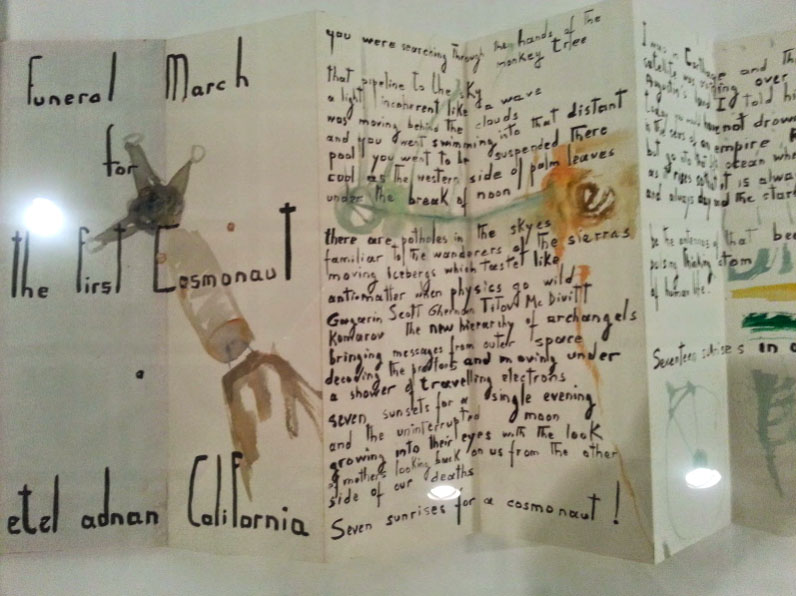

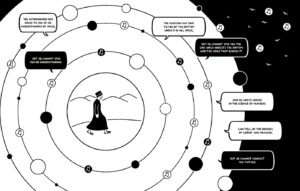

But there’s one little work, now on view at the very entrance to her Guggenheim retrospective, Light’s New Measure, which captivates my attention because of how much it relates to her first poem, and the journeys through time and life that Etel Adnan always encouraged the reader to undertake unprotected from ourselves and the world: This is the “Funeral March for the First Astronaut,” a leporello completed in 1968, in the form of a painted poem to the Russian astronaut Gagarin. Etel Adnan was fascinated by the space race, and had an idea, similar to Hannah Arendt’s, about our stellar journeys: Once one of us has left the planet, we all have left the planet with him.

In the 11th stanza, she returns to the sun god Ra of her very first poem:

“Astronauts are also mortal

Gagarin first man in space but also the thirteenth

the sun god Ra and murderous Isis

Elijah and Jesus and you

Mohammad hovering above Jerusalem

Refusing to enter Paradise but unclothed

And reduced to a heap of ashes

You prophet Elijah carried by your horses

Burning close to the sun

All of your cosmonauts carried by our dreams

Floating above sleep

All of you pioneers of that space

Which lingers between atom and dream

We heard the tremendous minute of silence

You all stood when Gagarin came to you

The great child in the great machine.”

Will she now ascend into the sun like Elijah, like Sun god Ra, like Gagarin? On the day of her death, Barış wrote to me at night: “She will pass into the rivers of infinity, not to find peace, because she is already there, but to be one with her infinite lover. Simone is in her eternity.” As it always happens with Etel, I said to myself, it is as if he had read her entire poetry; the ascent of love, the infinite, the one, the warm concept of love, as for Socrates and Alcibiades:

“There is but one sea; oceans, gulfs, bays, all of that is

One. This great reservoir is partly in glaciers, and partly in

Clouds. The sea is a strange spirit constantly changing form;

She’s a heavy liquid, she’s made of fog, cloud, snowflakes.

She’s a mix of gases.”

For years, it has been said that Mount Tamalpais in California, a place she knew intimately and about which she spoke often, and compared to the hills above Izmir, was for Etel Adnan, what Sainte-Victoire was for Cezanne, a site of exuberant vision, a site of repetition, or rebellion, but also of failure. It seems to me as if Etel’s work was incomplete at the time of her death as the work of any painter (not her poetry, her final book was already published), and Simone tells us that Etel Adnan kept working on the canvas, on the leporellos, day after day.

Now that Etel is gone, I can only think of the words that Maurice Merleau-Ponty had for Cezanne: “That is why he never finished working. We never get away from our life. We never see ideas or freedom face to face.”

“Sun and Sea” by Lamia Joreige and Etel Adnan was on view as a part of “A Yellow Sun, A Black Sun,” curated by Karina El Helou, at Martch Art Project, Istanbul, 07.09-30.10. Etel Adnan’s retrospective, “Light’s New Measure,” continues at the Guggenheim Museum, NY, through January 10, 2022.

Acknowledgements: Gregory Buchakjian, Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil Joreige, Karina El Helou, Lamia Joreige, Barış Yapar.

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)

Thank you Arie for your introduction to Etel Adnan. I just discovered your article after reading about Pierre Audi’s production at the Aix-en-Provence festival. My original enquiry followed my interest in Kaija Saariaho. Audi’s aunt was Etel’s partner. Her feelings for Smyrna are so touching. I hear in her voice the strength of endurance, so close to Rilke of the Duino Elegies. I am beginning a voyage of discovery of her work. Thank you.