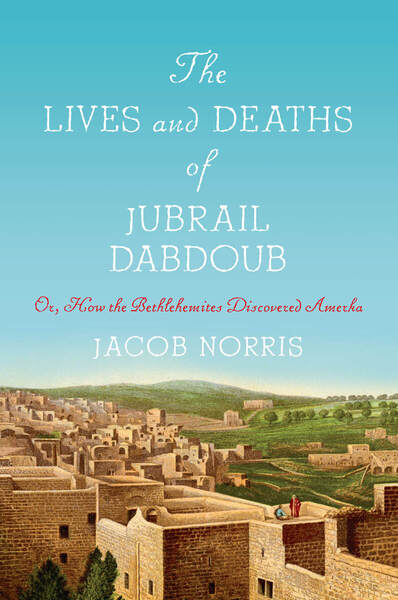

The Lives and Deaths of Jubrail Dabdoub, Or How the Bethlehemites Discovered Amerka, by Jacob Norris

Stanford University Press 2022

ISBN 9781503633285

Norris deploys strategies taken from magical realism and local folklore to create a vivid depiction of Bethlehem’s changes.

Karim Kattan

Bethlehem, seven kilometers from Jerusalem, is a multifaceted town and many seemingly contradictory things at once: at times a sleepy backwater, a rural community that grew too fast for its own good, a town oftentimes overlooked, a community obsessed with its own significance, and a globally connected city. Historian Jacob Norris’ The Lives and Deaths of Jubrail Dabdoub tells the story of how these many Bethlehems encountered the world in the late 19th century, through the life of a merchant, Jubrail Dabdoub. Norris explores the relationship between Bethlehem’s people and both local and global wonders, including jinni, saints, steamships, cities, and jungles as its sons and daughters, wily merchants and adventurous travelers, set out to explore the world. Through Jubrail Dabdoub’s story, as reimagined by Norris, who is a Senior Lecturer in Middle Eastern History at the University of Sussex, we also follow that of Bethlehem as it evolves, adapts, changes, and reckons with itself and its heritage.

Norris deploys strategies taken from magical realism and local folklore to create a vivid depiction of Bethlehem’s changes.

Norris’ book is not just about one change, but a series of changes that bring modernity, with its voyages and palaces and languages and business strategies, to Bethlehem. At the start of Dabdoub’s life, the world at large is far away and unreachable. Even the port city of Jaffa is a misty, remote place. But as Dabdoub grows up and travels, the world shrinks. People come and people go, on steamships and trains, more easily than ever. Merchants who settled in what is called “Amerka” in the book — the distant unknowable, be it the actual Americas, Europe, or Asia — come back to town looking for wives, connections, and traces of their home, resulting in a constant back-and-forth between local beliefs and global trajectories, spanning continents.

It Is thrilling to follow this journey. Norris’ lively narrative describes it through Dabdoub’s eyes, at first a wide-eyed boy who has barely seen anything beyond the edges of the forests of Wadi Ma’ali, then an international, cosmopolitan businessman and finally a world-weary patriarch who watches all he’s built vanish as change, again, comes to Bethlehem:

Returning home, he would pull out the maps he had drawn of Amerka based on Amma Hanna’s tales. Following the coastline, he would imagine himself on a great ship and wondered if one day he too would travel the road that stretched beyond Qubbet Rahil toward Jerusalem and the world beyond.

The Lives and Deaths of Jubrail Dabdoub is based on Norris’ academic research, but the historic work is largely left to the endnotes, where most of the heavy lifting is done. The curious reader can peruse Norris’ wide-ranging sources, through interviews, notes, diaries, and historic documentation. The research takes backstage here to provide a lively narrative with characters that are further imagined as protagonists of a novel. Lives and Deaths is neither a history book nor a novel: rather, Norris experiments with a hybrid form of writing which uses techniques from both.

As he explains it, “In trying to conjure these flashpoints through a magical realist style of narrative, I make no claim to literary merit. […] Rather, I offer an experiment in using some of the standard tropes of a literary genre to narrate a source-based historical project.”

The book, when it leans on the side of the novel, is somewhat a bildungsroman. We follow Jubrail Dabdoub from birth to death(s) as he travels to nearly every corner of the globe only to return each time to rural, then urban, Bethlehem. But Lives and Deaths is not a novel, nor does it pretend to be. It is somewhere in a liminal space between fiction and history, which can sometimes limit its effectiveness as either. The characters might occasionally appear as paper thin because the writer must do a balancing act between fiction and history, never being able to fully engage in one or the other. This is an understandable limit, which doesn’t dampen the pleasure of reading, as Norris uses an innovative form of writing. I find Norris’ experimentation with form daring. It serves as an invitation for others to explore this hybrid method and see where it can take them, what ways of telling history it can generate.

On the first evening, their boat from Jaffa had pulled into the gleaming harbor at Port Said, joining a long queue of steamships, waiting like well-mannered giants for their turn to enter the Suez Canal.

The other compelling proposal in the book is to take for granted that what the protagonists believe in is true, portraying saints and angels as real and closer to the protagonists than the improbable innovations of modernity: the text imitates “magical realist authors’ tendency to portray encounters with capitalist modernity in the language of wonder, enchantment, and absurdity, while relating interactions with spirits, saints, and the divine using more mundane, quotidian language.” Norris takes these beliefs seriously. The text’s form allows for a generous and deep understanding of the protagonists of the book, free of all condescension. It also serves to better understand one of the book’s crucial concerns.

The central scene towards which Lives and Deaths builds encapsulates the intersections of belief, business, wonder, the local, and the global. In 1909, a miracle is recorded: Jubrail Dabdoub dies and is resurrected by Sœur Marie-Alphonsine, whose story is a parallel to his. This Palestinian nun received several apparitions of Mary in Bethlehem in the late 19th century, directing her to create a congregation of Palestinian and Arab nuns, known as the Sisters of the Rosary. Marie-Alphonsine’s narrative is one of colonial religious encounters and can be read — though it is not only that — as a struggle to wrestle religious practice away from foreign practices to create or renew local models and modes of transmission: Marie-Alphonsine was “surrounded by haughty franji nuns with their disdain for Arab customs […] Her upbringing in al-Quds had rooted her in the local culture, and she could not prevent her Arabic tones from creeping into the French she was forced to speak with the sisters.”

Jacob Norris interprets this miracle as a typical intersection of local religious practices, family myth-building, and power struggles. The meeting of the trajectories of Marie-Alphonsine and Jubrail Dabdoub in a recorded wonder encapsulates how Palestine and Bethlehem existed at the boundary between many eras, geographies, and worldviews.

I am a son of Bethlehem myself, and not so distantly related to Jubrail Dabdoub. It is an odd position to be in when reading a book: sometimes, I had the egocentric, but electrifying, sensation of reading the story of how I came to be. I am familiar with many of the people Jacob Norris interviewed — including my grandparents and aunts and uncles — and have heard through their retellings several aspects of the Bethlehem described here. I occupy, in a way, a liminal space akin to the book: I am a reader but, as someone concerned by the subject matter in such a direct way, I feel also like an agent of this story, albeit a distant one — the type of offspring Jubrail and his brothers would have been somewhat proud and somewhat horrified at having spawned.

I came out of the book feeling I had understood aspects of myself better — and felt more rooted in my hometown of Bethlehem that has been global for a long time. In a sense, Bethlehem’s history is one of globality. Therefore, my position between Europe and Palestine, between here and there, between languages, felt more like home than ever, because it felt, for once, not like a freak accident or merely the result of nefarious colonial forces. It is also the result of historic and individual rationales, desires, dreams, that date from a century before, and that are an intimate part of me; one that I can also rejoice in. The lives of Jubrail Dabdoub and his contemporaries tangle and complicate binaries, shifting our understanding of notions of belonging, parochialism, and cosmopolitanism.

But there is, naturally, a sense of ownership and of protectiveness, when reading something that touches so close to home written by someone else. I was attentive to Jacob Norris’ sensitive understanding of the worlds he wishes to depict here. Before starting the book, I was curious to know: how will Norris, someone telling a story from an outsider’s perspective, manage to convincingly understand and convey that world? Norris touches upon the subject in his introduction: “Being open about the historical text as an artificial construct is especially important for a book about Bethlehem written by a historian from the UK — a country that relates to Palestine with an uncomfortable combination of physical distance and colonial proximity.”

Though this would warrant another, longer, conversation, Norris’ gamble — to take very seriously the beliefs of his protagonists/subject matters — is also a technique which disables — or attempts to disable — this problem: by its very nature, this type of writing forces Norris to engage in the worlds he describes; therefore, he is generous towards it subject, respectful of their worlds, and humble in his approach. In some ways, The Lives and Deaths of Jubrail Dabdoub is an exercise in humility — which is one of the greatest qualities a novelist or an academic could wish for.

Norris’ book is an impressive work that offers a captivating glimpse into the history and lifeworld of Bethlehemites in the late 19th century, as he masterfully balances history and fiction to create a hybrid form that is both imaginative and informative. While the book’s experimentation may occasionally limit its effectiveness as a novel or a history book, it also opens up new avenues for historians and writers to explore. By focusing on the intersection of local beliefs and global ambitions, Norris provides a nuanced understanding of how Bethlehemites navigated the rapidly changing world of the late 19th century.

And because it is a book about change in a small town, it inevitably touches on themes of death and dying worlds. Yet, the book is neither provincial in its scope nor funerary in its tone. Norris’ intriguing techniques breathe life back into those themes. The final chapters are particularly poignant as the belief in magic and intercession of saints disappears. Dabdoub’s world expands to a global scale but contracts in disenchantment. The Lives and Deaths of Jubrail Dabdoub is the story of this metamorphosis and of how Bethlehem, with all its uniqueness, quirks, and wonders, became part of the planet.

![Fady Joudah’s <em>[…]</em> Dares Us to Listen to Palestinian Words—and Silences](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/SAMAH-SHIHADI-DAIR-AL-QASSI-charcoal-on-paper-100x60-cm-2023-courtesy-Tabari-Artspace-300x180.jpg)

An excellent well written review. As a Bethlehemite it is easy to relate to the conclusions of this book.

Que libro más hermoso me llega muy de cerca ya que soy Dabdoub y vivo en Bolivia