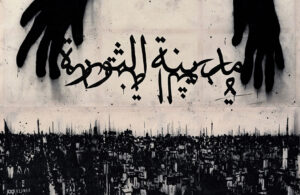

The Israeli army’s siege of Tulkarm has turned the city into a hunting ground for Israeli military incursions. Behind a wall of closures, Palestinians face, in addition to military raids and airstrikes, a deliberate campaign of killings, kidnappings, and arrests of men between the ages of 19 and 50 across the West Bank. One writer’s mission is to bear witness to the brutal arithmetic of conquest.

Another Israeli military invasion, August 18, 2025

At 6 p.m., frantic reports began circulating of Israeli soldiers gathering in large numbers and roaring like predators.

6:30 p.m., there was news about crowds of soldiers advancing towards Tulkarm.

7:55 p.m., heavy gunfire began, shortly followed by missile attacks. News outlets then began reporting that people were being injured in the district near the house belonging to my grandparents. My mother tried calling them, but nobody answered. My mother panicked, so she put on her headscarf and said, “I’m going to my father’s house.” All of us, fearing for her safety, protested. Although she assured us, “I’m going to navigate through the houses.” I decided to go with her.

On quiet days my grandparents’ house is about eight minutes away by car. However, under these circumstances, it was going to be a very long and dangerous journey. We drove cautiously, trying to avoid streets occupied by Israeli troops, until we reached a point where we were unable to advance any further. We stopped in front of a house, asked the owner if we could leave our car, and continued from there on foot. As we walked through the alleyway between the houses, we saw large numbers of heavily armed Israeli soldiers backed by military vehicles. When they opened fire on us, we jumped into a stranger’s yard and hid behind mounds of dirt as bullets whizzed past our heads.

Many did not even share their political opinions, because sharing an opinion was always pointless. Yet today they are all treated as threats to Israeli security.

In one alley, people had gathered. A Palestinian ambulance was trying to reach the wounded, but it was prevented from doing so. Social media pages began reporting an increasing number of casualties around my grandparents’ house. We kept asking people what was happening and then saw that my aunt, in her fifties, was standing there. As soon as she recognized my mother, she ran towards her and hugged her. They both started crying. They then decided that they would go and speak to the soldiers. However, gunfire forced them to retreat before they even got close.

Like tsunami waves, military vehicles began passing in front of us, their timing and direction unknown, as would be the extent of their damage, which seemed unavoidable. First came military jeeps, followed by the robotic IDF Caterpillar D9 bulldozers that demolish houses, and armored Tiger vehicles designed to hit anything in front of them, which also serve as transport for even more soldiers. A few minutes later, four big explosions shook the earth.

Some young men — the oldest of whom were 20 — set fire to rubble. The sky filled with thick, black smoke. They trailed behind the military, throwing stones in the hope of preventing or distracting the soldiers from more killing. Watching their bare Palestinian hands, I thought to myself, what’s a stone against advanced weaponry, AI programs, and murderous technology?

My cousin’s killing

Thirty minutes later, a cousin called and told me about another cousin of ours. “Rami has been killed.” There was nothing further to say. The call ended.

I froze, with the phone still to my ear. I was in a state of electric shock as though I had fallen from a cliff. I couldn’t move. Part of me was waiting and hoping that my cousin who had called would say that he had been mistaken and take back what he had said. I felt the blood stop in my body. My throat instantly dried. I glanced over at my mother, with her pleading eyes. But I was unable to utter a single word. I kept telling myself, let’s wait. Maybe Rami is still alive. Maybe he’s not the one who’s died. Maybe he’s injured — maybe, maybe, maybe. But the maybes felt meaningless. My mother already on her phone was reading the names of the martyrs circulating on social media. Suddenly, she fell to the ground and started sobbing. “This can’t be real,” she kept repeating.

My younger aunt, Alia, not expressing her fear, cried silently. Her eyes bulged. The sentences she spoke to people beseeching them to do something, anything, were incomplete. What can civilians do when attacked by a merciless army?

She looked at me, and asked, “Is this real?”

I said, “Let’s wait. It might be another person, with a similar-sounding name, a mistake.”

Her voice faded to a whisper, “These are lies.” She turned a vacant stare toward the gathering crowd. Her lips moved soundlessly before faintly uttering, “Lies… lies… all lies…”

Two and a half hours later, the names of the victims were published on Telegram but within minutes they were removed. Nothing had yet been confirmed, which effectively left 250,000 people collectively holding their breath as they waited to find out if their sons or relatives were among the dead or injured.

It was already around midnight when Israeli forces began to withdraw and return to their bases as though nothing had taken place. Needless to say, none of the soldiers were harmed. However, our lives had been turned upside down. In the dark, people ran through the streets searching for friends, brothers, cousins, fathers, mothers, and sisters — everyone looked for their loved ones. My mother’s youngest sister, Alia, has serious health problems. Yet, she lifted her black abaya — a traditional Palestinian dress of modesty — and began running towards my grandfather’s house. I went back to our car, and tried to follow her, since my mother had collapsed and could no longer walk. When we finally arrived at my grandparents’ house, a large crowd had gathered outside. We made our way through to the front door. On the left, under the jasmine tree, soaking into the ground was the blood of my cousin Rami and remnants of his flesh. At that moment our childhood memories together flashed through my mind like a film on a loop.

My mother and I went upstairs. In the middle of the living room my aunt Rudaina, the mother of Rami, the martyr, was screaming, “I want my son!”

My mother collapsed next to her, and they both started yelling. In my whole life I have never heard my mother raise her voice. Overcome, she beat herself. I tried to hold her hands and calm her down by hugging her, but I too was at a loss — what else could I do?

Then my aunt Alia arrived and my mother and her sisters began screaming and crying once more. The men in the family and the neighbors went to console them. Cold water was sprinkled on their faces to prevent them from losing consciousness.

One neighbor came in and began speaking loudly, “May he rest in peace.” He continued, “God gives sons, and God takes them away,” which he then told all of us to repeat after him.

The women quieting down whispered to each other, “May he rest in peace. May God forgive his sins and have mercy on him. Please God, forgive him.”

Our neighbor then started to recite verses from the Qur’an, asking for divine mercy. The women were more peaceful now. Then Rana, Rami’s sister, arrived with her three children from a village outside of Tulkarm. She paused at the door and looked intently into our faces one at a time. When she came to me I turned away. She then asked her mother, “Where’s my brother?” Rudaina started screaming and crying.

A man said, “This isn’t acceptable, stop shouting. Please pray for him.”

Rana turned on him, “Stop saying that. My brother is not dead. Rami was not killed. I want my brother.” She called to him, “Rami, where are you? Don’t mess around. I know you’re sleeping in your room. Rami, come out, come out, come out.”

Then she fell to the floor and immediately lost consciousness. Her face quickly went pale, and her body became extremely cold. It was soon clear that she had literally swallowed her tongue. She was suddenly short of breath. Her mother, unable to bear the sight of her incapacitated daughter, began hitting herself and screaming. Both lost consciousness.

Around the living room I saw that all the women of the family were all unconscious, on the floor. A Palestinian ambulance soon arrived; Rana and aunt Rudaina were taken to the hospital. There, they were given sedatives and treated. Until today, Rami’s sister has not been able to accept that her brother has been killed. Rana struggles with stress, depression, and grief. Every now and then she spends days in the hospital, after having swallowed her tongue.

As a form of solidarity, more neighbors and friends flocked to my grandparents’ house. I went out into the courtyard and saw blood. Its stench filled the place. Particularly pungent was the smell of death beneath the olive tree. Rami, my cousin, my dear childhood friend, is gone because young soldiers fired dozens of bullets into his body. He left this life as simply and brutally as that.

I went back home without my mother. I was trying to understand what had happened. I couldn’t sleep because of the shooting and bombing that took place all night long. In the morning, I went back to see my mother and the rest of the family. I peered into my aunt Rudaina’s face. In so little time so much had changed. At first, I didn’t recognize her because her wrinkled face seemed to sag down towards her shins. The red under-skin of her eyelids drooped from all the crying. Her body seemed physically smaller. She had suddenly become frail.

Men are being taken to dungeons of humiliation

I still haven’t fully come to terms with my profound grief, which I will never be able to get over. Even during this time of intense personal pain, Israeli soldiers came and raided many houses in my neighborhood and arrested my relatives, friends, and colleagues. Within a few more weeks, many young male friends began disappearing one by one.

This is part of a wider Israeli campaign to kidnap, arrest, and kill thousands of Palestinian men in the West Bank, aged between 19 and 50. It is the worst nightmare that any of us could imagine. Thousands of Palestinian men mainly in Jenin and Tulkarm have been stripped naked in front of their children, robbed of valuables in their homes, and beaten. It is an unending torture in which the men I know have been rounded up by Israeli soldiers and taken to unknown detention centers. This could happen to any family member, even if they have not done a thing.

A father, a brother, a son, an uncle, a neighbor, a colleague, I know each one of them. I live with them. I work with them. I am aware of the journey of their lives. They have always been committed ordinary civilians: teachers, engineers, nurses, farmers, photographers, paramedics, among many others. Civilians whose main concern has always been for their families to live in peace and stability. In the past, most of them did not even share their political opinions, because sharing an opinion was always pointless… and yet today they are all treated as suspected criminals and threats to Israeli security. Thousands have been forcibly disappeared, and held without charge. (According to the Palestinian Prisoners’ Club, there have been more than 17,000 arrests since October 7, 2023, up until May 2024. 3,562 is the number of administrative detainees according to HaMoked or the Center for the Defense of the Individual. These numbers do not include prisoners from Gaza or Palestinians who were taken away for shorter periods.)

Watching their bare Palestinian hands, I thought to myself, what’s a stone against advanced weaponry, AI programs, and murderous technology?

Eighteen months have passed since the start of the West Bank military offensive. Around 11:20 a.m., I walk through the market in the center of Tulkarm, where most of the streets and stores now lie in ruins. Many of the vendors are elderly men barely able to stand. In addition, a few pale, fatigued women sit beside broken tables — not even makeshift stalls — and sell homemade foodstuffs. In tattered black headscarves, they hope that a customer will buy something from them so that they and their families can survive another day. It’s hard not to notice that most of the people in the market — the women, children, and the old — are all silent. I do not need to ask why. Not only do I know the answer theoretically, I live it each and every moment. It is the absence of hope, opportunity, and justice in their lives that haunts me day and night. No one here can escape this.

In the month before April 2025, my colleagues, my brothers, my cousins, and my friends were kidnapped from their homes or from military checkpoints. They are all in Israeli detention centers, in humiliating conditions where infectious diseases spread and medicine is denied them. They spend their days, weeks, and months with insufficient food, without clothing, without blankets, without protection. They are voiceless and, for the most part, forgotten by Western media. These are not detention centers, they are inhumane dungeons, each cell no more than 30 square meters where as many as 28 men are confined. In the corner of the cell is a hole they call a toilet, which everyone is forced to use, without privacy or dignity. Time has become meaningless, since with the absence of sunlight, it is impossible to tell day from night. If anyone requests the most basic right, they are punished with severe beatings, starvation, or worse, sexual assault. These are dungeons of humiliation. They are a felony against human civilization. This hell is where more than 18,000 young Palestinians from the West Bank alone now live, in the dungeons and cages of Israeli administrative detention.

A conversation with death

Today, as I write this, I am sitting alone at a broken table. The café I’m in used to be popular. There is a hookah beside me. I smoke, and it burns slowly. The smoke helps me forget the smell of death that has permeated my life. Overwhelmed by successive rounds of incomprehensible and continuous oppression and torture, I sit here, smoking for hours. It’s as though I barely exist in the dust. I am dissolving into the haze.

I sit with my soul shattered, writing words that seem dead. I sometimes chat with the café owner, whose wretched expression is also etched with death. D9 Caterpillar bulldozers dug up the street in front of us, so we’re not really sitting in the café; we’re half-sitting on and in the rubble of the café. The surrounding uprooted and burnt trees lie dead at the side of the road. I’m alone with the café owner. We talk. I ask him if we’ve died or if we’re still actually living. We argue about religion, history, spirituality, causes, and reasons, but we find no answers to justify our existence. Then we return to the question: have we died? Could it be that we haven’t realized that we are already dead?

“Perhaps we’re in hell!” he or I say.

Suddenly, we look at each other and laugh out loud. Our laughter mocks life and everything that we think about it.

With a shaky voice, he says, “Who’s next? You, or me?”

We laugh again. What else can we do?

A final farewell to my dear cousin:

We were born two years apart in our grandparents’ home.

Raised in the same place, filled with memories:

The white jasmine tree…

The cactus fruits…

And the three olive trees at the back.

What can I say of our birth?

Our first cry…

When the world was filled with scorn?

Our dream is to go to the sky

My friend,

Did you leave to die, or…

You left to rise?

Was it rage you bore?

To flee this earth?

Go to the abode of peace.

Do not linger; do not heed us.

Let your soul find release.

Go, my friend, and never look back.

Let your heart rise above —

Quest for justice, quest for peace,

Seek the shelter of love.

What do my hands hold after such pain?

Why do I still write? To whom?

To the wretched world, denying us grace?

To this cruel world, unworthy of our embrace!

Go, my cousin… Go, my childhood friend…

And never look back!

Thoth is a pseudonym used by the writer to ensure their personal safety.

![Fady Joudah’s <em>[…]</em> Dares Us to Listen to Palestinian Words—and Silences](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/SAMAH-SHIHADI-DAIR-AL-QASSI-charcoal-on-paper-100x60-cm-2023-courtesy-Tabari-Artspace-300x180.jpg)