Select Other Languages French.

Mansoura Ez-Eldin’s new novel delves into the consequences of erased history. By weaving together elements of dreams, memory, and forgotten philosophy, it tells the story of a Cairo bookseller who is haunted by the ghost of a Muʿtazilite thinker. In a region where the act of remembering is often political, this book insists that some stories cannot be silenced.

The Orchards of Basra, a novel by Mansoura Ez-Eldin

Interlink Publishing 2025

ISBN 9781626499815

Mansoura Ez-Eldin’s The Orchards of Basra invites readers into a world of forgotten histories, lost wisdom, and intellectual longing. It’s not simply a novel of intellectual or political conflict; it’s a poignant exploration of what we lose when the forces of history and politics erase our past. The story weaves together two disparate worlds: the political turmoil of Cairo and the intellectual remnants of Basra, once a flourishing center of rational thought and reason in the Arab world.

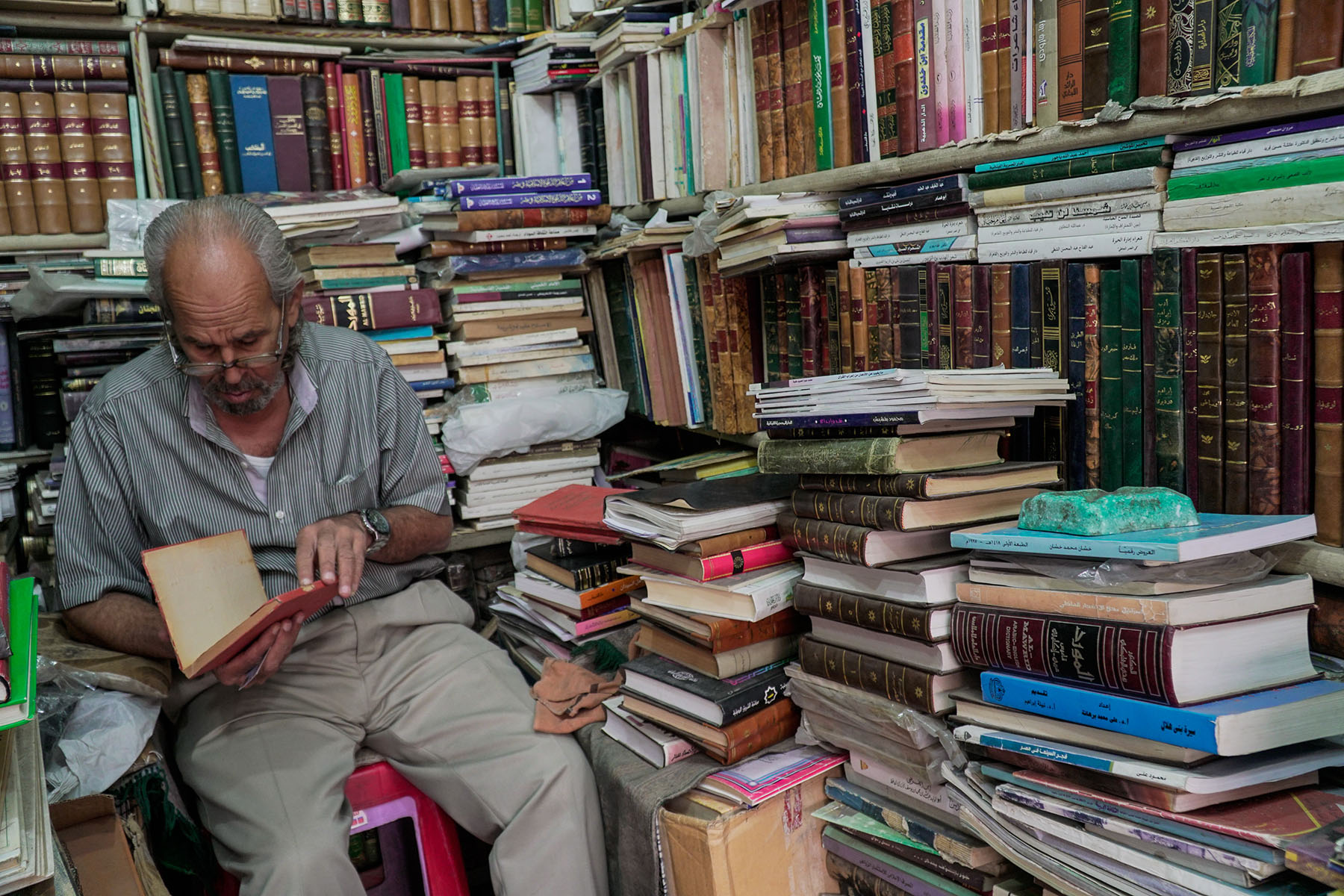

Basra, as it appears in the novel, is both a symbol and a setting. For Hisham Khattab, a Cairo-based antiquarian book dealer who becomes obsessed with Yazid ibn Abihi, a Muʿtazilite philosopher erased from history, Basra represents more than a city — it’s an intellectual oasis. Once the seat of rationalism and theological debate, Basra’s historical significance has been buried under layers of political and religious suppression. For Hisham, however, it is a place of mental escape, a mirage that beckons with the promise of something lost long ago. But as Hisham delves deeper into his search for Yazid’s legacy, the city begins to shift in his mind — from an idealized image of intellectual freedom to a reminder of all that’s been lost:

It was a dream of a land whose very name is laced with incense and sea spray, whose palms rise like script into the sky… Basra as mirage and archive, its orchards burnt and reborn in memory.

The city of Basra, as Hisham imagines it, is both distant and deeply tied to his intellectual and emotional struggles. It transforms from a place of escape to something more ambiguous — a reflection of the tensions between an intellectual past that once thrived and the painful realities of the present — a disheartening confluence of checkpoints, armed men, and ideological rigidity. Hisham’s pursuit of Yazid becomes a quest to not only recover a philosopher lost to time but also to reclaim the wisdom — hikma — that was once celebrated in Basra but has since been obscured by political and religious power.

In a city where even public spaces are overshadowed by surveillance and control, books stand as one of the few remaining spaces for true meaning.

At its heart, the novel is about this very concept of hikma — the wisdom that arises from reason, morality, and knowledge. The Muʿtazilites, who believed that faith must be guided by reason, embodied this philosophy. In a world that often prizes dogma over reason, hikma becomes a battleground. In this way, the novel’s focus on Yazid and his intellectual tradition is more than historical — it’s a direct comment on the intellectual and political forces that stifle reason and independent thought today.

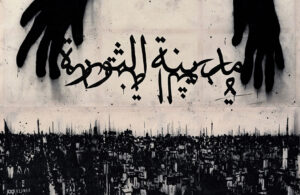

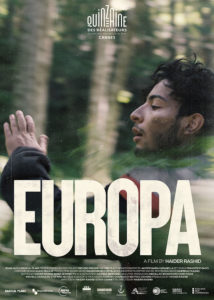

Contrasting with Basra, Cairo serves as the stage for Hisham’s present, a city pulsating with energy but constantly throttled by political control. Ez-Eldin’s portrayal of Cairo feels stifling and suffocating — its streets filled with the noise of state surveillance and political theater. One of the novel’s most striking images captures this sense of oppressive control:

The streets were emptied of meaning by the presidential motorcade. Sirens howled like stray dogs… Bella stood on the pavement, framed by the light of a bookstore window, cradling The Great Interpretation of Dreams like it was a newborn.

In this moment, Bella — a woman who briefly enters Hisham’s life — holds the book as though it is sacred. The book, in this case, becomes a symbol of resistance. In a city where even public spaces are overshadowed by surveillance and control, books stand as one of the few remaining spaces for true meaning. Bella’s reverence for the text feels almost like a quiet act of defiance, a reminder of the power of knowledge in a city that would rather silence it.

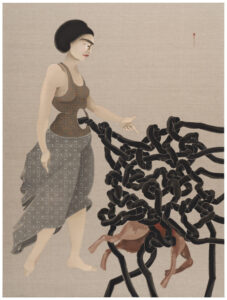

The bookshop, which is central to the novel, serves as another symbol — a place of preservation and decay. As much as it is a space where forgotten knowledge is preserved, it is also a site of intellectual decline, reflecting the erasure of past ideas. Hisham’s bookshop is filled with texts — some crumbling, others incomplete — each one representing a lost piece of history, a fragment of thought:

The air inside was thick with foxing, the cracked spines of volumes stood like gravestones. Manuscripts, many without covers or titles, leaned against each other in conspiratorial hush.

This space, with its aging manuscripts, becomes a metaphor for the intellectual decay that has taken root in societies where dissenting ideas have been systematically suppressed. For Hisham, the shop is both a sanctuary and a reminder of the intellectual decay that surrounds him. His search for Yazid is a quest to reclaim that which has been silenced, to rescue knowledge from the shadows of history.

The novel’s emotional weight also lies in its personal connections. Hisham’s relationship with the heretic, a scholar marginalized by both the state and religious authorities, is at the core of the story. The heretic, who represents the intellectual dissenter, becomes a mentor to Hisham, but also a mirror to his own struggles. In one particularly moving moment, the heretic holds a manuscript, not just with care, but with grief:

He held the manuscript like a mourner touching a dead friend’s face—gently, with disbelief. ‘They tried to erase him,’ he whispered, and I wasn’t sure if he meant Yazid ibn Abihi or himself.

This passage encapsulates the central struggle of the novel: the attempt to recover something that has been erased — not through intellectual defeat, but through political force. The heretic’s quiet sorrow reflects the broader tragedy of ideas and intellectual movements lost to time, their voices silenced not through reasoned debate, but through the power of political control.

At the novel’s core, the romance between Hisham and Bella serves as a subtle but powerful contrast to the novel’s intellectual themes. Their kiss, described as an uncovering of something hidden beneath the skin, reflects the novel’s exploration of silence, memory, and the things that remain unsaid:

When we kissed, it felt like uncovering a palimpsest — something inscribed beneath the skin. She smiled only with her eyes, as though words would cost too much.

This kiss isn’t just an act of passion; it’s a symbolic unveiling of something buried, something that can’t be easily expressed or understood. Just as Hisham seeks to uncover Yazid’s ideas, this kiss symbolizes the longing for that which is hidden, and obscured by time and power.

Hisham’s relationship with his father, another figure of absence and erasure, adds further depth to the novel’s exploration of loss. His father’s death — marked by an absence of identity and the lack of recognition — mirrors the intellectual erasure that permeates the novel:

My father died as he lived—unreachable, in another country, sending letters no one opened. When they buried him, they said he had no papers. That was the first truth he and I shared.

This passage speaks to a profound loneliness that runs through the novel — not just the absence of Hisham’s father, but the absence of identity and intellectual legacy that echoes throughout the story. Hisham’s search for Yazid, like his attempt to understand his father, is a search for connection — both intellectual and emotional — that has been denied to him by the forces of time and politics.

At its core, The Orchards of Basra is about the politics of memory. The Muʿtazilite thinkers, such as Yazid, represent more than an intellectual tradition—they represent the struggle for reason and the freedom to think in the face of political and religious oppression. The novel critiques how Muʿtazilism—which once emphasized rationality, moral justice, and reason—was gradually suppressed. As the novel makes clear, the erasure of Yazid and the Muʿtazilites is not just historical—it’s a present struggle:

The heretic claimed our rationalists were not defeated by theology, but by empire. That a single caliph’s decree could silence a school of thought for a thousand years.

This line captures the heart of the novel’s intellectual and political tension: intellectual freedom is not merely an academic issue but a political struggle. The suppression of knowledge and the erasure of ideas are ongoing battles, not only in the context of the modern Arab world, but in the west, where many would argue democracy is threatened by fascism.

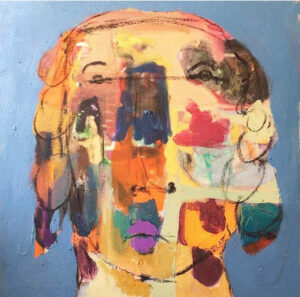

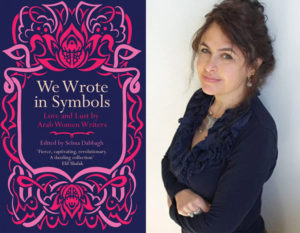

Gender is also a critical component of the novel’s meditation on erasure. One of the novel’s most striking lines comes from a female character who describes her body as a “footnote” — a reflection of how women’s voices and bodies are often erased or misinterpreted:

She said her body was a footnote—redacted, misread, always annotated by men. She called her hijab a bookmark, not a barrier, but even that explanation felt stolen.

Bella’s reflection on her body speaks to the gendered dimensions of erasure, highlighting how women’s identities, much like intellectual traditions, are often written over or ignored by dominant forces in society.

Ez-Eldin’s writing is layered and evocative. The Orchards of Basra is not just a story of intellectual rediscovery; it’s a meditation on the fragility of memory, the cost of reclaiming lost knowledge, and the battle for intellectual freedom. The novel’s central struggle — reclaiming Muʿtazilite philosophy from erasure — is a metaphor for the broader cultural amnesia that the novel critiques. It’s a story about fighting to remember, even when the forces of history and power are working against you.

The novel is a challenge to anyone who has ever questioned authority, searched for lost knowledge, or fought against intellectual silencing. It is a work of art that dares us to reconsider the stories we’ve been told, and those we’ve been taught to forget.