Yahia Dabbous

Looking within Cairo, it’s hard to escape the narrative that insists on a new Egypt. The New Republic, which resembles less of an institution-building vision and is instead presented as a silver-bullet solution to decades of stagnation in the picture of CGI’d next-generation cities that flash across billboards dominating the cityscape, has been promising pristine scenes of serenity and skyscrapers.

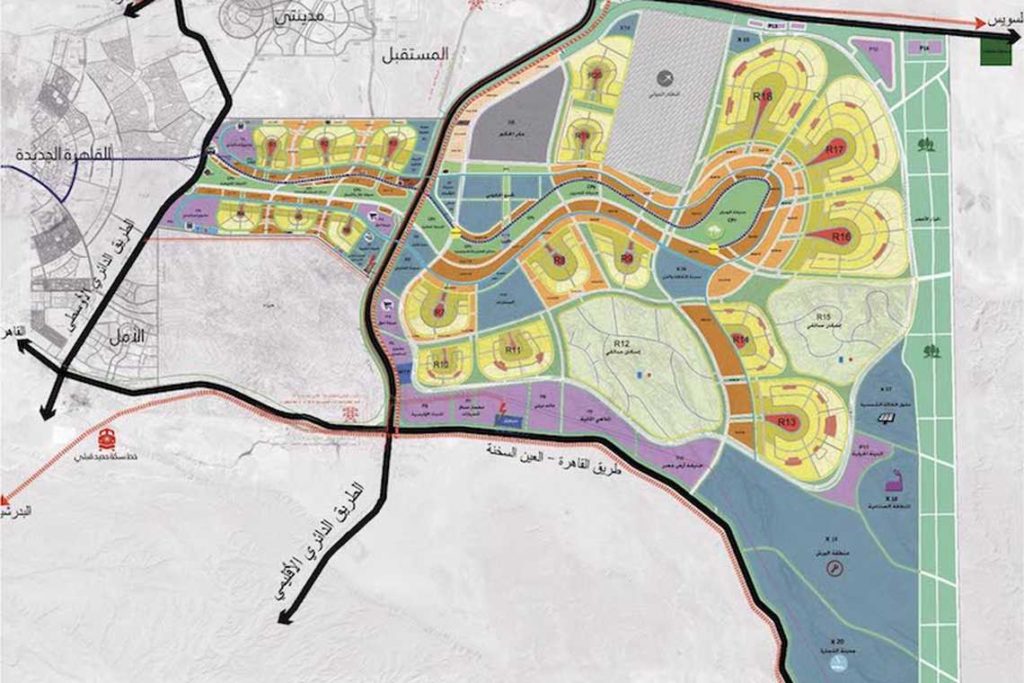

But while the New Administrative Capital begins to take shape, segments of middle-class Egyptians — for whom such projects are promoted to present a clean break from the overburdened Cairo — are skeptical about the New Republic’s assurances of modernity and technological advancement, dismissing the seductive images of utopia in satellite cities as little more than choreographed mirages.

The disillusionment stems from a perceived ballooning disconnect between the lived experiences of Cairo’s 20 million residents and the distant image of the New Capital. While Cairenes share an average of 0.8 meters of green space per person and the city’s rare leafy neighborhoods are seeing those centimeters shrink, the highways that recently pummeled through the former gardens lead to the yet uninhabited New Capital, where a park six times the size of New York’s Central Park is under construction.

Moreover, a recent walkout during a screening of Feathers at El Gouna Film Festival serves as an illustration of the uncoupling of reality and narrative. Sherif Mounir, a popular Egyptian actor, led the walkout at the grandiose annual festival to protest the negative portrayal of Egypt in the film’s depiction of slums. “Those slums we had are disappearing now,” he stated in an interview with MBC’s El Hekaya. “Even in the poor areas, people don’t live that badly,” he claimed, before declaring that “we are now in a New Republic.”

Given that official state statistics indicate that the majority of Egypt’s urban population live in informal settlements, this broad chasm in perception of the country’s condition can be considered a hyperreality, a concept devised by French philosopher Jean Baudrillard to depict the state in which one is unable to distinguish between reality and a simulation of reality.

Within this cloud of uncertainty, a flurry of Instagram accounts doubling as informal collections and archives has emerged, capturing overlooked, often unnoticed substructures, charms, and frustrations of Cairo’s daily realities.

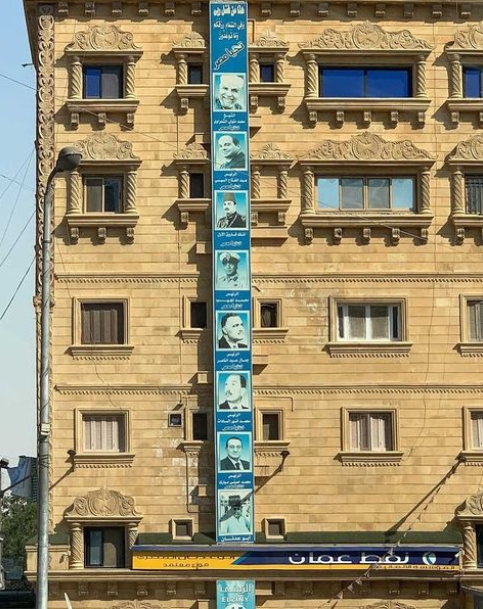

One such account, @spotsh3rawi, showcases the ubiquitous presence of Muhammad Metwalli al-Sha’rawi, a popular late scholar whose interpretations of Islam have endured authoritatively. By simply photographing portraits, posters, and paintings of the Sheikh in arbitrary, everyday settings such as on microbuses and private vehicles, or at kiosks and storefronts alongside figures such as Oum Khalthoum or former presidents, the account exhibits the extent to which Sha’rawi has been mythologized in the popular Egyptian imagination.

Elsewhere, @sabils_of_cairo celebrates the networks of self-sustenance in the free water sources and fountains voluntarily placed across the city, a testament to the charitability of Egyptians; @borto2archive documents abandoned orange and tangerine skin littered across Cairo, presenting an aesthetically pleasing picture to the unsavory sight of rotten fruit.

@yetanotheraccountaboutchairs, meanwhile, looks at the distribution of unsanctioned, DIY chairs that permanently occupy pavements, explaining to The Markaz Review that they hope to “find a correlation” regarding the street chairs, looking for patterns within their arrangement and use. They are usually created by and reserved for doorkeepers, says the administrator, who also likes to think that each individual design is customized to exhibit an element of their personality through them.

Each Instagram account serves as a brushstroke of a niche Cairene hallmark, contributing to an evocative, resonant portrait of the city, one which helps resists the embellished mirages of its hyperreal narratives.

Stickers and plastic epitomize disposability, but some accounts make them a little more permanent. From the perspective of the passenger seat, @stuckincairo is a collection of bumper stickers seen on the road that doubles as a spectacle of common sexism, aggression, and God-fearing declarations, as well as a snippet of absurdity. Meanwhile, @mannequinofegypt allows us not only to be bewildered by a Santa Claus mannequin in fiery lingerie showcased across a store display window, but in its more routine images it can gradually sketch unpretentious and unusual wardrobe trends of the day.

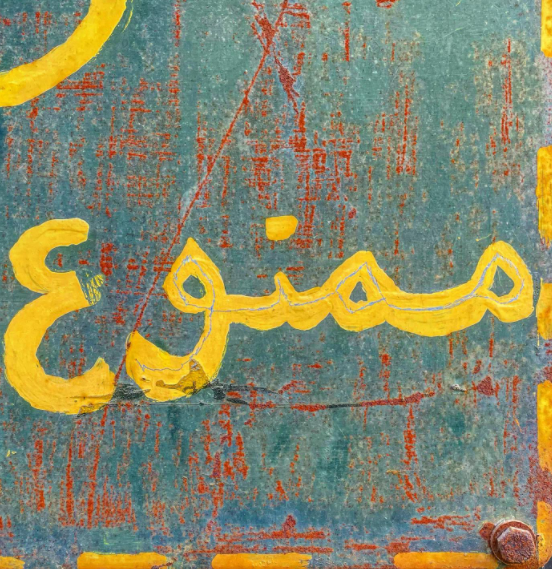

These accounts, of which there are dozens — documenting everything from heart symbols to the calligraphic variety of ‘forbidden’ signs, messy murals of Mohamed Salah and sound — range in their self-descriptions from archives to collections and diaries, and usually they appear to simply be for fun, not dissimilar from meme pages. But in a country where official archives are shielded from public view, too sensitive to be accessed even by researchers, the accounts operate not only in an archival vacuum, but in an environment in which the collective capacity to simply make sense of Cairo has been fractured by design.

Nour El Safoury, an editor and film critic who leads classes on mapping informal circulation of media at the Cairo Institute of Liberal Arts and Sciences (CILAS), says the spatial class-based divisions within Cairo result in wildly disparate perceptions of the city’s essence, and that this phenomenon of informal digital archives are a way “to navigate the urban space to create your own commentary from your position and from your experience.”

Speaking with The Markaz Review, El Safoury notes that while the quality and information of documents in traditional archives vary dramatically from those found in informal ones, the ways in which these pages function resembles practices found in standard archives and collections. “In documenting, you’re interested in how a particular moment in time or in reality is preserved,” she says. “With archiving, it is about how to make those artefacts come together to allow someone in the future to make sense of a moment in the past.”

She explains that archiving requires telling a story, and that the narrator’s authority is stronger when it is a pluralistic narrative featuring different viewpoints. For institutional archives, donations are crucial to this, while Cairo’s informal Instagram archives are typically operated by an anonymous administrator who encourages submissions to broaden the collective perception of a certain artefact that symbolizes Cairo’s vernacular. But can follower submissions uphold the function of plurality?

El Safoury says that standard archives often lack a diversity of voices in their storytelling, generally relying significantly on a small pool of donors and contributors for the majority of their material, which raises the question of who gets to document a moment. Additionally, the circulation and study of archival records is predominantly limited to researchers, while public consumption and access has been sporadic.

If we are to consider these accounts as representative, informal archives preserving a memory of an everyday Cairo threatened with erasure from official narratives of and by the New Republic, then we must heed that they too are flawed as a record of this moment. Broadly, accounts often post in the English language, photos are frequently geo-located to more affluent districts within Cairo, or lack date and location details entirely. Additionally, accounts often cease their effort entirely and without explanation, or deviate from their initial artefactual focus, perhaps inevitable given their informal, uncompensated work.

@firehorsecairo is an illustration of this: initially marveling at the pervasive omnipresence of a stock photo of a horse on fire that advertises advertising space on Color Studio’s wealth of billboards, the account has broadly substituted its content to varying forms of light-hearted horse memes. Still, its earlier documenting of the firehorse artefact was invaluable in helping us simply perceive a visual feature so prevalent that the everyday gaze stopped noticing it, in the same way we don’t notice our own nose.

This phenomenon may not be exempt from myth-making in its artefactual storytelling, as its agents too can be unreliable narrators.

Yet these administrators operate within a dramatically fragmented social consciousness, resulting from the wild disparity in accounts of the city’s reality. What they do achieve is to bring observers closer to a more resonant, accurate model of Cairo. By collecting images of artefacts excluded from hyperreal narratives, they attest to their actuality, and by defending the sovereign distinction between real and simulation, these collections may not only inform future comprehension of everyday life in contemporary Cairo, but can help today’s Cairenes escape the dizzying narrative of a New Republic that, for so many, is simply out of sight.