Preeta Samarasan

My mother despised liars. In her mind, the pursuit of truthfulness was what distinguished her from my father and his siblings, who were unredeemed frauds: unfaithful to their spouses, shameless enough to steal from their own mother, who herself stole what she fancied from the neighbors. Their dishonesty was the main character in my mother’s stories, the star of the show, the eternal punchline. And then your aunt drilled a hole in the mahogany cupboard and took out all your grandmother’s jewelry. And then your grandfather just paid off the police for all those flower pots your uncle had stolen from the Town Hall. Can you believe it? The things they let their children get away with. Never corrected them.

Her greatest fear was that her children, having inherited the dreaded Ganapathy blood, would grow up to be liars. Had she read Francis Bacon at the time, she would have agreed with him that “it is not only the difficulty and labor which men take in finding out of truth, nor again that when it is found it imposeth upon men’s thoughts, that doth bring lies in favor, but a natural though corrupt love of the lie itself.” The only way she knew to snuff out this love was to correct us, a word that covered a multitude of methods: beating my brother when he came home with an eraser she knew was not his; shaming us for blurring the line between real and make believe; refusing to trust us for months after she caught us out in a lie. Vaaiya thorandha poyyi! she would scold in Tamil, often before she had proof we’d lied. Only open your mouth and out comes a lie.

My mother did not say that what she hated were lies that hurt others unnecessarily. I’m not sure she could have accurately summarized her position on truth, all its various caveats and appendices, all the clauses and case-by-case exceptions she never articulated even to herself; like other parents of her place and time, she laid down unambiguous rules because she believed them largely to reflect her thinking. Where our parents were aware of holding more complex views, the nuances were deemed too much for us to digest. Why confuse matters with context? Truth was good; lies were bad. If you had questioned my mother, she would have told you this was basic morality, boiled down only very slightly. No one has considered the nuances of truth-telling and lying, nor outlined them with greater honesty and finesse, than Mark Twain does in his essay, “On the Decay of the Art of Lying”:

“What I bemoan is the growing prevalence of the brutal truth.

Let us do what we can to eradicate it. An injurious truth has no

merit over an injurious lie. Neither should ever be uttered. The

man who speaks an injurious truth lest his soul be not saved if

he do otherwise, should reflect that that sort of a soul is not

strictly worth saving. The man who tells a lie to help a poor

devil out of trouble, is one of whom the angels doubtless say,

“Lo, here is an heroic soul who casts his own welfare in jeopardy

to succor his neighbor’s; let us exalt this magnanimous liar.”

Of course, a truth that is injurious to one person or one group of people may be liberating to another; a lie that may seem unnecessary to some may feel necessary to another. Our messy lives require us constantly to weigh the harm of a lie against the benefit of it, whether we do so consciously or not. Nearly every truth is both injurious and beneficial, as is nearly every lie. Which leaves us with the uncomfortable work of figuring out who can be injured and who cannot: whose needs outweigh the other’s at any given moment (for tomorrow, or later today, the answer might be different)? Who matters more?

One day when I was eight, I came home from school and told my mother I’d made a new friend. Her name was Shirley Thompson, she was English, and her family had just moved to my hometown. Shirley was blonde and blue-eyed; she had a posh accent and charming manners; she was, of course, completely fictional.

For years afterwards, I would try to relive the moment when my mother had asked me how my day at school had gone and the first sentence of this epic tale had come out of my mouth.

Vaaiya thorandha poyyi.

In hindsight, the lie would come to seem completely unnecessary. Often, when my mother questioned me in the years that followed its exposure, I would answer: I never expected you to believe me! This version seemed plausible, that I, an imaginative child who was forever babbling to my mother about the characters in the books I read, thought she would recognize that Shirley Thompson was just such a character, except that I’d invented her myself. When she didn’t throw her head back and laugh, I felt trapped in my own story, left with no choice but to continue it. For months, I doled out my daily Shirley updates to my fascinated mother: Shirley’s father drove a red sports car; her mother wore belted dresses and matching high heels. Now her grandparents had arrived from England for a visit. Her grandfather whittled wooden toys for her; her grandmother knitted tea cosies. Every detail was so clearly the clumsy concoction of a child who knew England only from the already outdated books of Enid Blyton and Rumer Godden and Noel Streatfeild. Even as I produced these stereotypes, I was half mystified by my mother’s failure to identify them as fake, all the more so because my brothers immediately did. From the moment they first heard about Shirley Thompson, they snorted with laughter whenever her name came up. I would watch them mock my mother for her credulity, and then, like a spectator at a tennis match, I would watch my mother defend me: Why would your sister lie about such a thing? Don’t be so mean. How would she come up with such stories? She’s too small to make up such things.

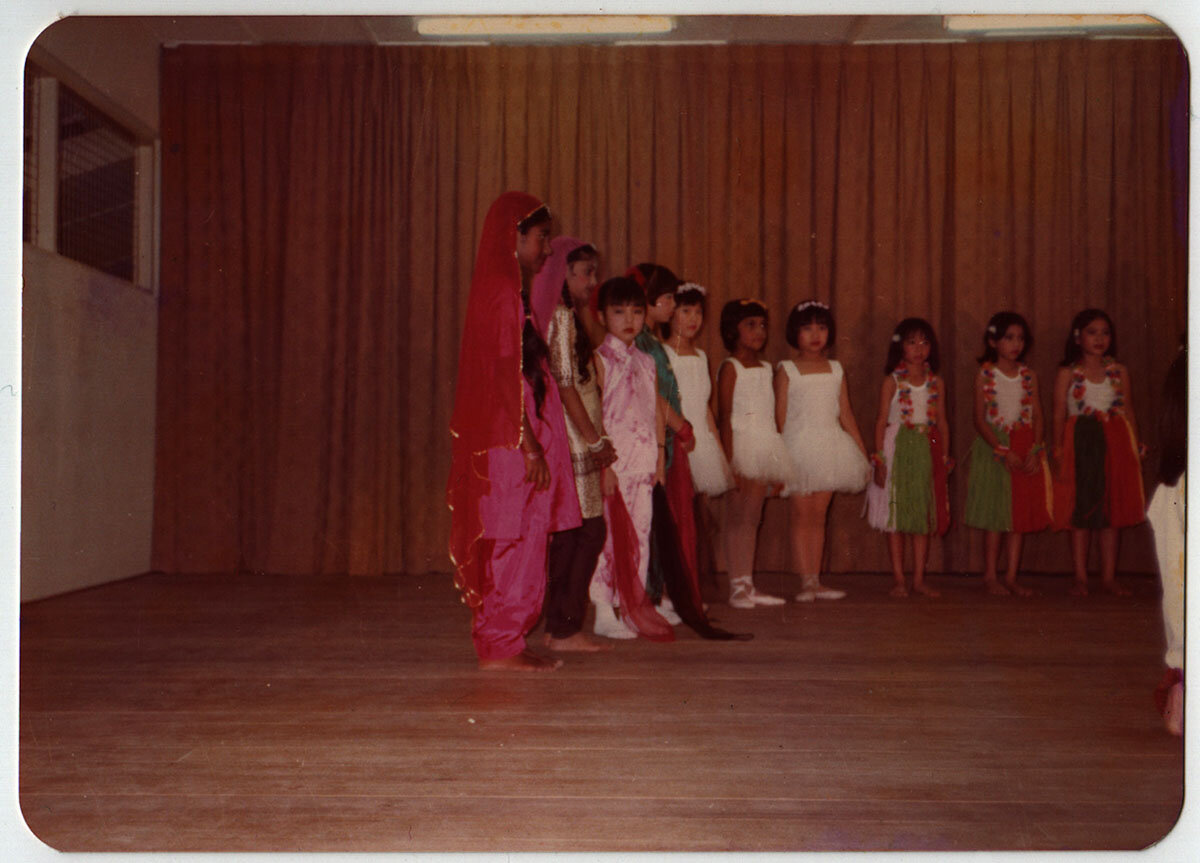

Every criminal wants to be caught, claims the cliché. Whether that’s true or not, my trail of clues grew increasingly bolder and more desperate, the descriptions of Shirley Thompson’s life ever more farcical, until, finally, I spun my final web right across a doorway I knew I would have to walk through: I told my mother that in the school concert for which my entire class had been rehearsing for months, the ballet segment was to be performed by me, my friend W., and Shirley Thompson. Shirley, of course, had studied ballet in England for years before moving to Malaysia. Her ballet slippers were made of real satin. She owned her own tutu, pale pink with sequins on the bodice.

In real life, the third ballet dancer was Chinese, like W. As the date of the concert drew nearer, I knew that soon, the burden of Shirley Thompson would be lifted off my shoulders forever, but first, I would have to endure my mother’s disappointment, my own humiliation, and my brothers’ triumphant mirth. How’s Shirley Thompson keeping? one or the other of them would ask me from time to time, smirking. Practicing hard for the concert? Yes, I would reply, stubborn, fierce. Yes, she is.

Looking back, I sometimes wondered how consciously they’d been offering me an escape route — listen, we don’t believe you, so you don’t need to keep going with this — and how consciously I was refusing it. Had I entered so fully into the game that my fury at their knowing smirks was authentic? Was I angry that they did not buy my mother’s version of me — she’s too small to make up such things — even though I knew she was wrong? I don’t remember my feelings well enough to answer any of these questions, just as I don’t actually remember why I made up the story to begin with. Maybe I just wanted to give my mother something interesting, finally, in return for the daily tedium of having to ask about my day at school.

Or maybe I thought I deserved a story like this, a harmless escape from the stresses of my real life: my parents’ terrible marriage; my father’s debts; the ever-present weight of being Indian in Malaysia, which came with a looming future my mother never let us forget. You have to be ten times better than others to make it half as far, she warned us. Raising us with strict time tables and clear goals, she’d made sure all three of us started school years ahead of our peers: multiplication tables mastered, world capitals memorized, reading the classics while many of our classmates were learning the alphabet.

My parents would not able to afford to send us abroad to university, but because we were Indian, we would be last in line for public university places and government scholarships. Unlike more privileged parents, my mother didn’t have the luxury of trusting that we would be fine if she loosened her grip on the reins, and to this day we have no assurance that we would have been: she did what she thought she had to, and what, in as much as it got us out of the country for our education, did work. Ten times better meant not just perfect marks in every exam, but also whatever advantages she could think of that might set us apart from the competition for foreign scholarships. You must try to be the best at everything you do, she told us, and so we did try, so hard that when my father’s accumulating debts should have made music lessons and French lessons impossible, my teachers offered to teach me for free.

A year into primary school, when I invented Shirley Thompson, I would already have been subject to my mother’s towering expectations when it came to tests and exam rankings. Did this make the lie necessary? Obviously not. Did the benefit of the lie outweigh its harm? I don’t know. Depends whom you ask, is what I might have felt at the time. Depends whom you ask: it might still be true today. My mother would say no, that the lie was a betrayal, that she found it difficult to believe anything I said for years afterwards. But to determine where I stand, I have to remember who I was when I was eight years old. What was the benefit of the lie for that little girl? What relief did it bring her, what joy, from what terrors did it distract her, even for a few short months? “Truth,” Francis Bacon himself had to admit, “may perhaps come to the price of a pearl that showeth best by day; but it will not rise to the price of a diamond or carbuncle, that showeth best in varied lights. A mixture of a lie doth ever add pleasure.”

On the evening of the school concert, while my parents were getting dressed, I told my mother I was going to call Shirley Thompson to find out if she was ready. I picked up the receiver of our orange Bakelite telephone and pressed a few buttons in a random order. Then I acted out one half of a conversation, expressing shock and horror, emoting like the child actors I’d seen on television. What? I exclaimed. Why did you go and do that? Oh no!

My mother came running out of her room, saree half draped, hairpins in her mouth. I sighed dramatically, said Ok, bye, see you soon, and hung up. “Shirley dyed her hair black!” I told my mother, my voice trembling. She felt so self-conscious, being the odd one out, she’s been complaining for weeks about how everyone was going to be staring at her blonde hair. Everyone stares every day, you know, she’s so tired of it. She must have thought, it’s bad enough when the other girls stare, but tonight hundreds of parents are going to be staring too!

For a brief moment, my mother and I just looked at each other. That’s it, I said to myself, it’s done, at last she doesn’t believe me. My stomach was icy, my hands shaking. My heart raced the way it did after every piano exam, every stage performance. It was done, it was done, I could let myself come back down to earth now.

But my mother’s eyes widened, and, taking the pins out of her mouth, she said: How could they let her do that? Eight years old and they let her dye her hair! Sometimes these English people have no brains.

I remember, even in the last minutes before stepping out onto the stage, wondering if one of the two Chinese ballerinas was perhaps pale enough to be white-passing. After all, the audience was so far away that no performer’s eye color would be apparent from out there. Or perhaps my parents’ gazes would be so glued to me that they would forget to look at the other dancers at all. I kept an irrational hope alive, against all evidence. Under the bright lights, I wouldn’t have been able to make out my parents in the audience even if I’d looked for them. For those few minutes, I lived completely in the moment.

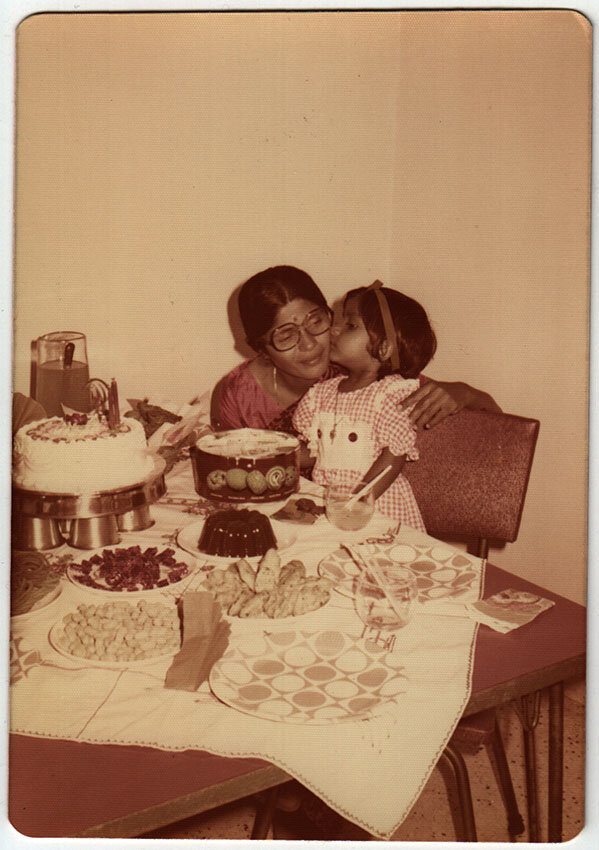

Walking out into the school hall after the concert, I caught my mother’s eye from a distance. She had one hand to her mouth, laughing, shaking her head. “What, you!” she said, as soon as I stood before her. “Your Shirley Thompson was a big bluff! All bluff! It was a Chinese girl!”

For many months afterwards, the tale of Shirley Thompson had to be relayed to anyone who hadn’t heard it. My brothers had already wearied of the amusement; for them, Shirley Thompson’s failure to materialize could be nothing but an anti-climax. But others had to be told, wonderingly and at great length: how and why could a child have taken the tale so far? No one said to my mother: many children make up stories. She knew only that in her own childhood, she had never made up such a story, nor would she even have dreamt of maintaining it for so long for her own parents. For many years, she would bring Shirley Thompson up from time to time, to ask me again why I’d done it, didn’t I care that I’d made her look like a fool for defending me against my brother’s accusations, didn’t I feel bad seeing how gullible she was? I simply believe everything people say, she would say sadly, and the implication would be that I had understood this and taken advantage of it. I’m still not sure she was wrong. But it wasn’t until I had children of my own that I finally said to her, one day: you know, it wasn’t that unusual. Children make up stories. I didn’t say out loud the rest of what I was thinking: you were the parent. It was your job to say you knew I was pretending, and then let me choose whether to carry on pretending. Don’t you see, I wanted to ask her, that pretending can be a respite? That’s what the bigger person gets to do: allow it, or not.

The Truth Is What We Believe

Mark Twain, again:

An habitual truth-teller is simply an impossible creature;

he does not exist; he never has existed. Of course there

are people who think they never lie, but it is not so – and

this ignorance is one of the very things that shame our

so-called civilization. Everybody lies – every day; every

hour; awake; asleep; in his dreams; in his joy; in his mourning;

if he keeps his tongue still, his hands, his feet, his eyes, his

attitude, will convey deception – and purposely. Even in

sermons – but that is a platitude.

Many religions claim to cherish truth while encouraging or even requiring innovative definitions of it. Observant Jews can carry medicine and babies on the Sabbath by putting up a wire to turn everything within this boundary into the private domain; a woman can fulfill the obligation to cover her hair with a lush wig more attractive than her own hair. To the outsider, such people appear to be exploiting loopholes in their religious laws. Yet an omniscient God is, by definition, privy to every lie. Belief in this omniscience is what led Francis Bacon — drawing from Montaigne before him — to conclude that a liar “is brave towards God, and a coward towards man. For a lie faces God, and shrinks from Man.” But what, then, do we make of faithful collaborating to maintain a lie? Then such followers must believe that God wants them to appear to keep the law even when they are unable to uphold it in spirit. Nowhere is this insistence on appearances more important than in laws against apostasy. Like Alice, an apostate declares to the world: “There’s no use trying. One can’t believe impossible things.” God, of course, already sees everything from the tiniest seed of doubt to the total absence of faith, but anti-apostasy laws concern themselves with what your neighbor sees, not with what God sees. If you fail to keep up the pretence of faith, you will risk anything from fines to death, depending on which country you’re lucky — or unlucky — enough to inhabit.

In February this year, Rosliza Ibrahim, a Malaysian woman in her thirties, won her six-year legal battle to be officially recognized as a non-Muslim. One may first ask why Ibrahim could not practice the religion of her choice without taking the matter to the courts. After all, how can any court order a person to believe something they do not believe? The answer lies in Malaysia’s treatment of Muslims, whose behavior is rigorously policed. As long as you are Muslim on paper, which you automatically are when you are born into a Muslim family (and by Malaysian law, all ethnic Malays must be Muslim), you are subject to state surveillance. You can be questioned or detained for not praying, for not fasting, for being gay or transgender. Anyone you marry must convert into Islam; your children must be raised Muslim. What Rosliza Ibrahim therefore wanted was freedom not just of thought but of action. Yet far from being a landmark victory for religious freedom in Malaysia, the judgement in her case hinged upon the fact that she was “an illegitimate child” who had never practiced her Muslim father’s religion. The judge took care to distinguish Ibrahim’s case from the famous Lina Joy decision, in which a Muslim plaintiff had failed to have her conversion to Christianity legally recognized. Nor was Lina Joy’s the first such case; others have lost similar battles. Unless it can be proven that you were never Muslim, or that you were converted without full consent, such as in the case of children who are unilaterally converted by one parent, it is almost impossible to leave Islam in Malaysia. Much easier to pretend, perform, lie; one must conclude that sharia law in Malaysia, like Mark Twain, has no use for the brutal truth.

Since the Rosliza Ibrahim verdict, two more cases of alleged apostasy have surfaced in Malaysia. In one, Nur Sajat, a well-known Muslim transwoman who has long been persecuted by the state, announced her decision to leave the religion after the Islamic affairs department deployed 122 officers to arrest her; in another, a Hindu man released a video explaining how he had converted his Muslim wife to Hinduism. On social media, public reactions to these incidents include numerous calls to violence: declarations that it is halal to spill the blood of apostates; demands that Muslims who leave the religion should be subjected to a “comprehensive reeducation process” and then punished if they do not repent. While Western observers tend to dismiss such voices as “extremist,” the fact is that many people who hold such opinions identify as moderate Muslims in Malaysia. The requirement that a sceptic or an unbeliever simply lie “every day; every hour; awake; asleep; in his dreams; in his joy; in his mourning” is a mainstream one in my country. The very notion of “respect” for ideologies in which we ourselves do not believe implies regular lies of omission, which are themselves the scaffolding of every conflict-averse culture.

When I was a little girl, we had an elderly neighbor who would drop in for long midmorning chats with my mother. One day, while telling us about a recently married daughter who had moved to England with her husband, she declared: “I told her, if he asks you to make thosai, idli, and so on, just say you don’t know how. Otherwise for the rest of your life you’ll be sitting and making all that.” This advice was my first inkling of my elders’ fickle regard for the truth. My mother and the neighbor shared a conspiratorial giggle, and to this day my mother, wishing she herself had known of such strategies, marvels at the old lady’s foresight. With one blithe lie, a woman could hobble the patriarchy, steal a small slice of her freedom back from the institution of traditional marriage, and her thosai-hungry husband would be none the wiser. The trick was in the timing of it, the lie told at a juncture in the marriage when burdensome expectations could still be nipped in the bud. Surely the prescribed lie was one that would “help a poor devil out of trouble,” even if the poor devil were the liar herself. Just say you don’t know how: an elegant lie, fulfilling the most fundamental prerequisite of successful lying, which is to say that it was completely sustainable. A less experienced liar might have shied away from this audacious, all-or-nothing approach, opting for daily drops of untruth as needed: say you’re not feeling well, say you’re tired, say they were out of urad dhal at the shop. But small lies require further lies, each one with its own risks, and before you know it, there you are, flailing in your own tangled web. The genius of this lie lay precisely in its one-fell-swoop victory: no one can ever disprove that you simply don’t know how to do something.

Sustainability: how often do we think of it when we decide to lie? A spur-of-the-moment lie is often unsustainable, but one understands such a liar’s ensuing dilemmas, even if one doesn’t forgive them. Harder to understand the unsustainable lies that are incubated over time: Shirley Thompson, for example, could not have tumbled off my tongue fully realized if I had not spent some time imagining the character, selecting the right details. Even so, being only eight, I must not have considered the great risk of being found out. Prizegiving days, exhibition days, sports days, school photos: Shirley Thompson was not going to be present for any of these. An apostate in Malaysia, if they do not take their case to the courts, makes an informed choice to sustain their lie for life. If we think of the decision in these terms — as a single decision made at one moment in time — it seems impossible than an adult should make it. But a lifelong lie is really just a series of small lies, each one made as the need arises. And so it is for many lies that turn out to be unsustainable: in the moment when we tell the lie, the future conceals itself. One day at a time, our self-preservation instincts tell us.

Just get through this moment, just buy yourself some time: struggling with undiagnosed depression, my mother, who despised liars, must have felt this each time she begged me to lie to save her from visitors she didn’t want to see.

Vaiyya thorandha poyyi. Only this time, the lies that came out of my mouth had been put into it by my mother herself: No, there’s no one else at home. Amma’s in hospital. Amma’s gone out and I don’t know when she’ll be back.

First, the bank officer who delivered her threatening speech about what would happen if my father didn’t pay our mortgage. Second, the aunt who bustled into the house and busied herself with all the tasks she thought she needed to do for a motherless household, and yet did not find my mother in the bathroom. Third, the aunt who did find my mother, because the house we’d rented when the bank repossessed our old home had only one bathroom. “That was a terrible position to put you in,” this aunt said to me afterwards. “That wasn’t fair.”

When I think about falsehood now, I often remember this line. Even as a child, I sensed that what my aunt was saying was not that the lie itself was unforgivable, but that it was wrong to drag others into our lies, especially when choice and consent were clouded by the balance of power.

There can be no balance of power more unequal than that between an omniscient, omnipotent God and His devotees. This God knows that a social media influencer with ten million followers is anything but “modest” despite her choice to wear the hijab or niqab. Yet — we are asked to believe — He favors the influencer in the niqab over the influencer in the bikini. What does “modesty” mean to an influencer like Malaysia’s Neelofa, whose niqab only renders her coy poses more suggestive? What does “modesty” mean to exquisitely made-up women whose carefully filtered selfies show off their lush lashes and full, parted lips, hijab notwithstanding? This is performative modesty: veiled to satisfy God (before Whom we are all anyway naked), on display for the adoring audiences, who shower these women with compliments both for their beauty and for complying with God’s law. But if “a lie faces God and shrinks from man,” the face that “modest” influencers turn towards God is not a defiant glare but a complicitous wink. They have fared better than I did as a child forced to lie for my mother’s sake: while women’s clothing choices are complicated by the weight of religious, social, and cultural pressures, no one is forced to be a social media influencer. That particular lie, the lie of immodesty labelled modesty, is one they’ve freely chosen, and the God in whom they believe might even applaud their clever circumventions of His restrictions. He is the bigger person; He gets to allow the lie, or not.

Literature is full of liars: those who lie to themselves, like Edward Ashburnam and Ishiguro’s Mr. Stevens, and those who lie to others. In this latter category are the ones who lie for the intoxicating pleasure of it, because “romance at short notice” is their specialty, as it was for Saki’s Vera, whom we understand as an embodiment of fanciful female girlhood. But those who deceive because they are desperate for the favor of the powerful: these liars are a subcategory onto themselves, and they are often children, for the obvious reason that children are often in a position to crave attention and approval. The Go-Between, Atonement, The God of Small Things, the list of great novels in which child protagonists discover the devastating power of the lie could go on, but these three examples suffice to illustrate the complicated reasons for which children lie.

The other day, investigators in France confirmed that the 13-year-old girl who triggered her father’s crusade against Samuel Paty, eventually costing Paty his life, had lied about being in class on the day of the Charlie Hebdo discussion. 13 — exactly the right age for romance at short notice. Or did she believe herself to be telling her father a lie to help a poor devil out of trouble? In this formula, she would have been the poor devil, suspended from school for behavioral problems, trying to redeem herself in her father’s eyes. But even Mark Twain’s attempt at complexity is ultimately inadequate in a world where multiple balances of power frequently operate at the same time: the heroic liar need only take one step to emerge, in different light, as an injurious liar. Yet the solution cannot be to tell the truth without exception, brutal or not.

In the end, it is with truth as it is with all things: we must admit that there are no immutable rules; that we have little control over our lies and our truths once we tell them; that all we can do is to trace the porous boundaries between truth and falsehood, power and vulnerability, with our eyes wide open.