The Republic of False Truths, a novel by Alaa Al Aswany

Translated from the Arabic by S. R. Fellowes

Penguin Random House 2021/July 2022 paperback

ISBN 9780307947345

Aimee Dassa Kligman

Alaa Al Aswany’s original novel in Arabic (جمهورية كأن), which translates as The Republic, As If, was published in 2018 by a Lebanese publishing house, Dar Al-Adab, as no Egyptian publisher would dare touch the work. It was subsequently translated to French as J’ai couru vers le Nil (I ran towards the Nile) the same year by Actes Sud, known for its translation work of foreign texts and award winning authors. It was translated to English by S. R. Fellowes, but was only released in the US in 2021.

Al Aswany, author of the internationally acclaimed The Yacoubian Building, has been an outspoken leader of the pro-democracy movement. He was highly critical of the Mubarak regime, authored political columns, held salons and was a co-founder of the group Kefaya (“Enough”). He has continued to criticize the current leadership in Egypt.

Despite his age, he was very present during the 18-day massive demonstrations in Tahrir Square, in which a majority of Egypt’s educated youth participated and which eventually led to Hosni Mubarak’s resignation. When Abdel Fattah el-Sisi came to power though a military coup, Al Aswany was banned from writing, publishing, and from appearing on TV.

Autopsy of a Revolution

It is well known that Egypt’s 2011 revolution failed. Nonetheless, The Republic of False Truths is expertly written, giving the reader an intimate perspective of Egyptian family conflicts, government collusion and military abuses of power. Had we not been told that this is a work of fiction, the story as authored by Al Aswany would seem entirely plausible, with only names changed, and personal lives imagined. We are introduced to several characters in their respective environments at work and at home. The reader will need to recognize that in Cairo, the neighborhood in which you live reveals your social status or that of your parents. Your place of study or work will also disclose to the reader your intellect, your influence (or lack of) and how connected you are to the ruling class.

Al Aswany fictionalized themes of corruption, police savagery, class exploitation, and totalitarian rule, as well as the political and social outrage that drove many Egyptians during that period. One of the undeniable conclusions we draw from this novel, according to its author, is that Egyptian Muslims suffer from ignorance about their own religion and the tyranny of their rulers. Oftentimes, Al Aswany accuses them of cowardice and submission through the voices of his characters. It is important to note that at no time does the author speak in his own voice. He has reiterated in several interviews that in all of his writings, the characters develop “a life of their own, and run away from him.”

However, there is no fiction to be found during “The Battle of the Camels,” the “Maspero Massacre,” the deliberate release of prisoners to counter the Egyptian revolutionaries’ extraordinary determination, the infamous “Virginity Tests,” (emphases mine), that were shamelessly conducted by an immoral and perverted military force, and three real life accounts of torture by female victims (only the names were changed to protect the women who still live in Egypt).

Al Aswany’s nostalgia for Egypt’s cultural glory in the ’50s and ’60s makes him overestimate not only the liberal atmosphere of the country under Gamal Abdel Nasser (president from 1956-1970), but also the strong lack of opposition to Islamism. You would only need to watch any Egyptian film from the 1930s to the 1960s to see the Egypt he cites. During that period, women did not wear the hijab or niqab, and nearly all women were unveiled, including the students of the religious Al-Azhar University.

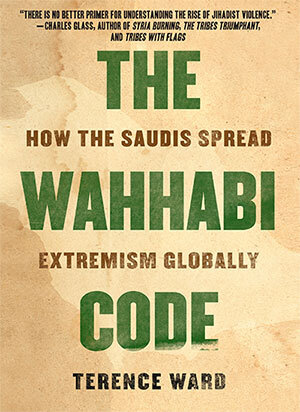

Whereas he frequently denounces Saudi Arabia and its Wahhabi interpretation of Islam as one of the greatest threats to Egypt and possible democratic reform, he doesn’t include, or ignores, the very real threat posed by Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood, founded in 1928 by Islamic scholar Hassan el Banna. After WWII the Muslim Brotherhood acquired a reputation as a radical group prepared to use violence to achieve its religious goals. The group was implicated in several assassinations, including the murder of a prime minister. Al Aswany also fails to mention that Egypt’s loss in the 1967 war was the main cause for the expansion of religiously inspired political activism which accompanied rejection of Western culture.

As for Saudi Arabia’s Wahhabism, to which Al Aswany refers as “Islam of the Desert,” it loomed large after the oil crisis of l973, and became the most rigid and punishing version of Islam. Wahhabism is used to advance a political agenda in order to retain power, and resembles fascism. There are copious references in The Republic of False Truths of characters traveling and living in Saudi Arabia, and returning to Egypt dramatically “altered.” Another frequent implication is that success is equated to landing a job in “The Gulf.” This naturally will take the applicant to any of the countries bordering the Persian Gulf, including Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE. All of them are top violators of religious liberty, according to the most well-known indexes of international religious freedom.

Saudi Arabia spends billions to spread the Wahhabi ideology; they have also contributed large sums of money to Egypt’s nearly six million Salafis, who are known for their doctrinal intransigence and strong condemnation of any group or movement that does not share their religious views. That particular threat which has its nexus in Alexandria is not mentioned in the book.

Several young, educated characters of the story categorically refused to work in “The Gulf.” It is worthwhile noting that there is a generational abyss in the Egyptian mentalities of the ruling class, between the adults who have lived a lifetime under authoritarian rule and today’s Egyptian youth, who have seen the world via the Internet, and yearn for freedom.

A cast of fictional characters appears successively in the book. The reader will never hear Al Aswany’s voice, but rather his characters will speak on his behalf. These include:

-

General Ahmed Alwany, Head of the SCAF; an extremely pious man with a penchant for pornography (“which is not considered a major sin like murder, fornication or the consumption of alcohol”) and is quite adept at ordering his underlings to torture and slaughter citizens. When he realizes what is happening in Tahrir Square, he proclaims that a conspiracy by the West is at hand. His wife, Hagga, is the mother of his three children, and has an unhealthy obsession with the Muslim Brotherhood.

For his safety, Egyptian dentist/author Alaa Al Aswany is currently living in exile with his wife in New York City, where he has been teaching creative writing workshops and giving talks at major universities. This is where he wrote The Republic of False Truths. All of his books are banned in Egypt, even though his 2002 best seller, The Yacoubian Building, was translated into 34 languages, and published in more than 100 countries. It was also adapted for film. Two more acclaimed novels followed, Chicago (2009) and The Automobile Club of Egypt (2016). The New York Times has suggested that Al Aswany is the biggest selling novelist in Arabic, Yasmina Khadra not withstanding. Al Aswany’s favorite author is said to be Fyodor Doestoevsky. -

Danya Alwany, daughter and favorite child of General Alwany. An accomplished student of medicine who does not obey her father. She is heavily influenced by Khaled Madany, and eventually falls in love with him. She goes to Tahrir Square against the advice of her parents.

-

Ashraf Wissa, a Coptic “failed bit player” and lover of hashish who despises his wife Magda, and has no relationship with his two children, Sarah and Brutus. He is a rare vestige of a bygone elegant and aristocratic era. By far, Ashraf is the most interesting character, as we watch him develop from a cynic to become an engaged participant in the revolution, brought on by a chance meeting with Asmaa.

-

Asmaa Zanaty, a teacher of English at a girls’ school and a member of the Kefaya movement. She is strong willed, rebellious and is not easily dissuaded. She falls in love with Mazen when she sees him at one of their political reform movement meetings. A staunch supporter of the revolution in all its aspects.

-

Sheikh Shamel, the community’s religious teacher who received no formal religious education, but rather obtained a university degree in Spanish. Worked in Saudi Arabia as a sports club administrator for a decade, after which he returned to Egypt and decided to proselytize Wahhabism (for which he is handsomely paid). He’s indecently wealthy. “He is said to have taken the virginity of 23 young girls, all in compliance with holy law.”

-

(The above character is representative of the way Al Aswany caricaturizes his cast)

-

Ikram, Ashraf and Magda’s maidservant. Unpolished and uneducated, she is an honest and loving character throughout the story. She has a young daughter Shahd, and is married to a drug addict. In one of her conversations with Ashraf, she declares: “Poverty is ugly, Ashram Bey.”

-

Mazen Saqqa, a chemistry graduate from Cairo University and an engineer at the Italian owned Bellini cement factory. A political activist and member of the Kefaya movement, where he finds “a group of the most courageous and noble Egyptians.” He falls in love with Asmaa and they engage in what seems to be an interminable correspondence. In one of his letters, he writes to her: “our battle is not with the headmaster, it’s with the corrupt system that produced him.” Here again, we are hearing the voice of Al Aswany through one of his imagined characters.

-

Essam Shalan, aka “Uncle Fahmi”: manager of the Bellini cement factory, and a close friend of Mazen’s deceased father. He marries Nourhan in spite of the wide difference in their ages. A Marxist since adolescence, he is quite vocal against the bourgeoisie, and refuses to live with self-deceit. He attempts to school Mazen in the realities that have diseased Egypt. A diabetic alcoholic.

-

Nourhan, a very attractive, opportunistic and deceitfully religious woman. She becomes a heroic TV personality and eventually Director of Programming at the state sponsored TV station. She seduces married men to obtain a luxurious life. Uses her position in the media to spread “fake news.” Akin to Fox News.

-

Madany Said Abd El Wares, a widowed devoted father of two, Hind and Khaled. He is Essam’s chauffeur and trusted confidant. His son Khaled is his glory and reason for living. He also undergoes a transformative experience during the revolution.

-

Khaled Madany, a medical student and son of Madany, mild mannered and not swayed by religious teachings. He is his father’s pride and joy, though, in one conversation, he tells him: “What complaint, Hagg Madany? We’re in Egypt. Injustice is the rule.” He is in love with Danya. He displays enormous courage when confronted by the savage officers of the Egyptian army.

-

Muhammad Zanaty, father of Asmaa, whom he considers an affliction. Spent a quarter century in Saudi Arabia and was profoundly influenced by its culture. An accountant by trade. He suffers from diabetes and high blood pressure. He prefers to let his wife, who is unnamed, to handle his daughter Asmaa.

-

The Supreme Guide, head of the Muslim Brotherhood. The group was severely restricted under the rule of Hosni Mubarak, and yet, they play an important role in the counterrevolutionary effort.

-

Muhammed Shanawany, a corrupt millionaire businessman with close ties to the Mubarak family. Assisted Alwany in setting up four major state TV channels whose purpose was to broadcast the theory of a conspiracy planned and funded by the CIA and the Mossad. People were paid to appear on those broadcasts to provide false testimonies.

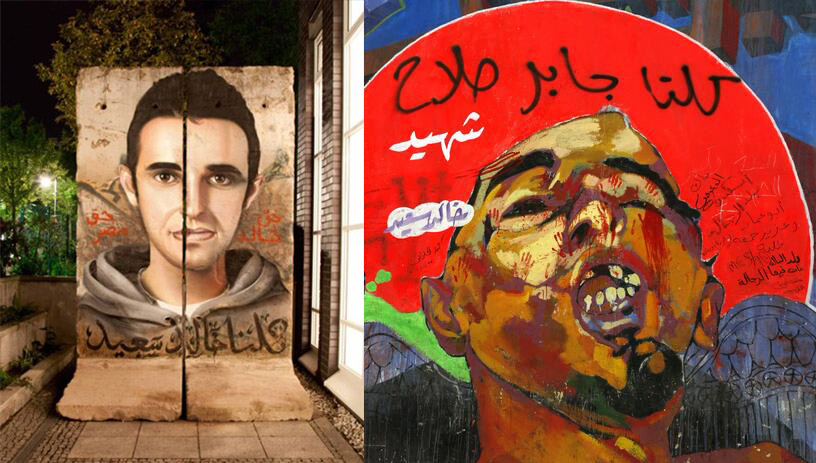

The events of January 25, 2011 were triggered by the brutal torture and murder of a young student/blogger Khaled Saïd by the police in the city of Alexandria. He is mentioned by name in the novel. Here are murals from the before and after photos of Khaled Saïd.

Blatantly missing from the book, and a fact that should have segued in relationship to Khaled Said is the name of Wael Ghonim, or at least, an imagined person in the narrative who could have easily been recognized as Ghonim.

Wael Ghonim was, in many ways, the face and the fallen hero of the revolution. As Google’s head of marketing for the MENA region, and very active on social media platforms, he was able to teach and mobilize young Egyptians to rise in protest of a tyrannical government rule. The new enlightenment economy (Facebook, Twitter), of which he possessed considerable currency, enabled previously impossible collaborations and coalitions. It introduced new platforms for communication and mobilization, which caught the regime by surprise.

Ghonim was arrested in Tahrir Square and subsequently detained blindfolded for 12 days. He granted a couple of interviews after his release from jail, one of which I was able to view on CNN.

Any account of the Arab Spring in Egypt must include Ghonim’s voice who was a de facto spokesman for the revolution. He was invited to speak with the Minister of the Interior; Ghonim was also the administrator of the Facebook page titled “We Are All Khaled Said,” which he created following the death of the young man at the hands of Egyptian police.

By January 28, 2011, tens of thousands of Egyptians had been mobilized by means of social media, which turned into a smorgasbord of demands directed at President Hosni Mubarak’s 30-year autocracy. They bravely fought security forces, attacked police stations, burned government buildings, and chanted “bread, freedom, justice,” as well as “erhal” (Arabic for “leave”).

The various storylines involving the main characters all contribute to the events leading to the crescendo of the revolutionary effort, and eventually to its demise. Having personally invested much time watching the failed revolutionary coup in January 2011 and its aftermath, the contents of the book have crystallized for me many of the horrific elements which could not be detailed in the media.

As I contemplated the meaning of the narrative, I began listening to a few interviews of Al Aswany, one of which was particularly edifying in understanding the spectacular uprising and dismal failure of the revolutionary undertaking. Though none were specifically about The Republic of False Truths, the interviews, held in English and French, served to elucidate the author’s position on Egyptian society.

One particular interview was held in Frankfurt in 2019, conducted in French by Daniel Medin. Al Aswany mentioned the name of a French political theorist/philosopher named Étienne de La Boétie who had written a treatise in Latin in the 16th century, which was eventually translated to French in 1576. He wanted to demonstrate that a dictatorship could not exist without the consent of the populace. The Discourse of Voluntary Servitude was most likely written when de La Boétie was 17 years of age. The relevance of the premise becomes clear:

This text consists of a short indictment against absolutism which astonishes by its erudition and depth, as it was written by a young man. This text raises the question of the legitimacy of any authority over a population and tries to analyze the reasons for the submission to it [“domination-servitude”].

The brilliance of La Boétie’s thesis is to argue that, contrary to popular belief, servitude is not imposed by force but voluntary. If this were not the case, how could one conceive that a small number of individuals would force all other citizens to obey so subserviently? In fact, any power, even when it is first imposed first by force, cannot sustainably control and abuse a society without the collaboration, active or resigned, of a majority of its members.

Having remained in constant contact with Egyptians (both expats and in situ) since my family’s personal exile from the country in 1962, the why and how of a dictatorial regime became crystal clear, as I found a number of Egyptian citizens to be completely oblivious, or perhaps purposefully ignorant of and/or denying the iron-fisted dictatorship wielded by Abdel Fattah el-Sisi. Incomprehensibly, many Egyptian women go as far as lauding his accomplishments. An Egyptian woman expat I befriended on Facebook once wrote to me: “We prefer our leaders to be military men.”

Back to the book. If we know the outcome, why bother reading it?

Al Aswany, with his usual flair, is a master storyteller and gives us a documentary of sorts to understand the Egyptian quotidian: what each of his characters think, feel and do in response to a myriad of situations. We’re invited to explore the divide between the small, albeit enormously wealthy elite and the working class, between domestic workers, students and the unemployed. It is impossible to ignore his lampooning of the forces which control the population — the armed forces (in the name of national security, always) and the religious operatives (Allah be praised, this is haram).

How can Egypt call itself “Umm El Donia” (Mother of the World) if it conducts itself so immorally? Al Aswany takes aim at the hypocrisies of power, especially the patriarchal kind, and shows how political crises can divide families along generational lines. He does not spare us the fanatical regression and oppression of women by sexually obsessed men, who soothe their lust by demanding that women cover themselves. Their repressed libido is in glaring evidence during a scene depicting the rape of a young man, and flagrantly during the “virginity tests” obscenities.

As to why the revolution failed? The book does not go that far, but failure is implied in various chapters as we watch injustices unfold, and hopes and dreams are crushed by the counterrevolutionary forces. Would it have been different, had there been a cohesive, alternative political party which could have taken over, and given the Egyptian people a choice outside a military dictatorship or a theocracy? Perhaps, but there would have also been a need for all institutions which are completely corrupt to be replaced…