Each morning an Egyptian student in Budapest wakes up to embody a new character as she navigates the challenges of being a foreigner and overcoming language barriers to learn about the city and its people.

Nadine Yasser

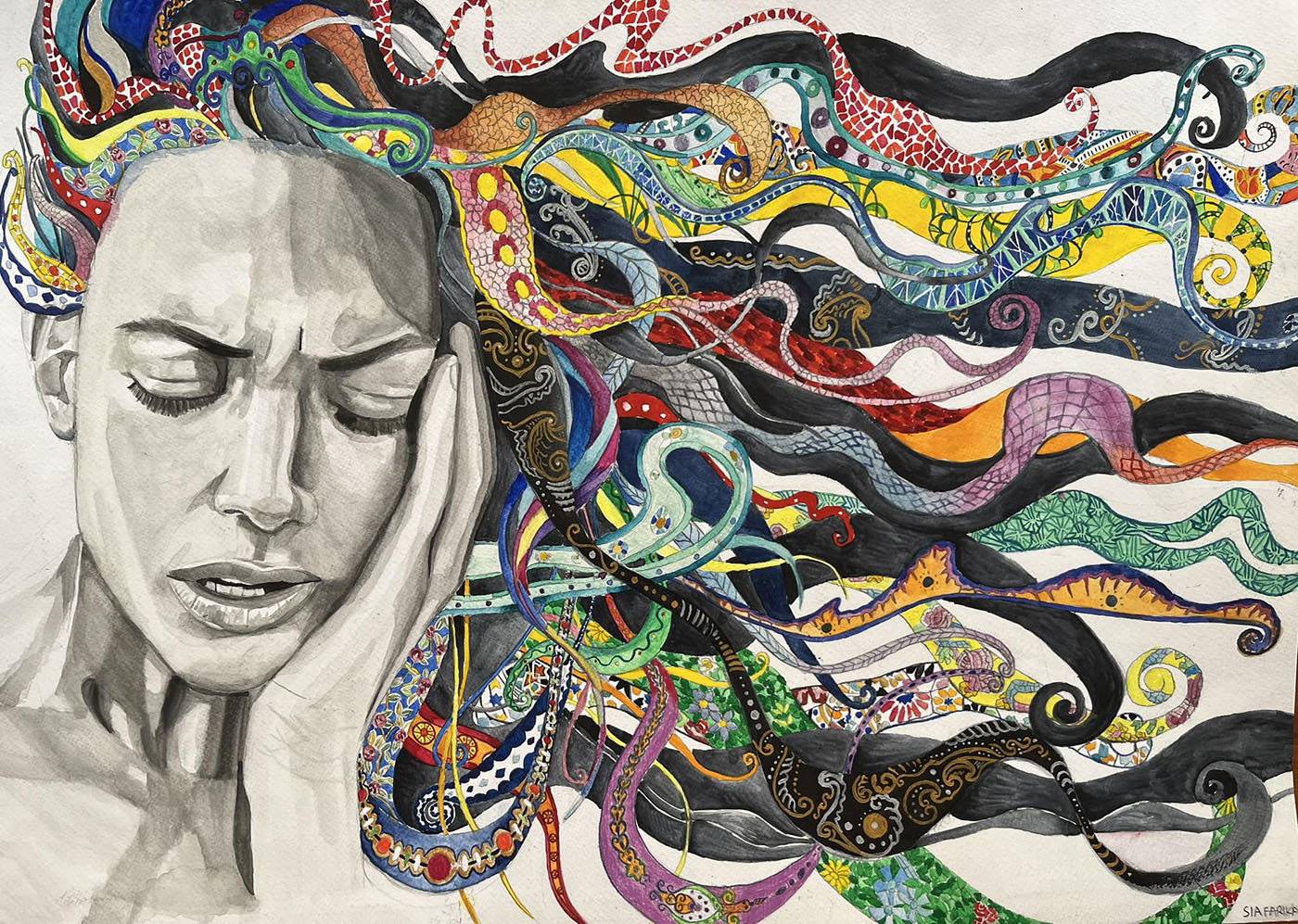

Every other day, it feels like I’ve borrowed someone’s skin. I steal their singular quirks, guffaw with the unique ring of their laughter that fills a room, and confront the manner they are perceived by those around them. I’ve never been the same person for two days in a row. With every sunrise, a shift happens, seemingly noticed by no one other than me. The people I choose to be do not necessarily have much in common. Many of them lie on opposite ends of a diverse range of spectrums. It seems impossible to sleep on many days, forced awake by an unconscious urge to meet the person I will be for the day. Missing sleep because I am too wary to let go of today, or too impatient to meet tomorrow.

Today, I woke up with a heavy body. The sunrise was long gone and it was a fresh start to meet with whoever I was to be for the day. Given my state, it was an easy decision: I was going to be nobody at all. My goal was to simply savor whatever the day brought and to think of nothing. That, however, proved to be impossible. Everywhere I go in Budapest reminds me of days when I was something and someone other than what I am today. For example, walking past Vajdahunyad Castle brought back memories of a particular sunrise in the same place. On that day, I knew I was to be an aspiring actress, on set for the first time with an actual role. The sun was rising behind the castle, in a mixture of orange, pink, and lilac, and there was not another soul on the street. I couldn’t help but think of Cairo — my hometown — where I was unlikely to go out at any time without finding company. As a child, I constantly fantasized about having the world to myself. That’s what it means to grow up in a city where life never pauses. Budapest was the opposite, and at times like that sunrise, I felt that I owned the world. All I could think of while walking to my pick-up location, surrounded by a picturesque sky and the freezing cold air, was this is not my life; I’m filling in for someone else.

I hadn’t thought of it much when I got the call from the casting agency. I signed up with them purely out of need — your typical college student fending for herself in a big city, and willing to look for sources of income in every corner. I enjoyed working on sets, regardless of how big or small my job was, but the call for this shoot was different. My face would be appearing in a scene, albeit as I dragged around a dead body. Naturally, I agreed.

“Remember, you’ve done this a million times. You’re emotionless!” The director told me for what felt like the hundredth time that day. I would’ve been perfectly emotionless while pulling the so-called dead body, but when we started shooting the scene, I realized that the lead actor was someone I had idolized since childhood.

I knew exactly the sequence of actions that had led me to where I was standing that day, yet I still felt like a stranger to my own reality. I remember asking one of the assistant directors if the actor was really who I thought it was, to which he responded Probably, before proceeding to complain about the cameraman being an idiot. I remember thinking how that specific assistant director had enough personality to fill an entire room. The problem with being on a set is that this applies to everyone there, and in the end, there’s too much personality and no place to breathe.

After I was dropped off from the set, in the same spot I had witnessed the sunrise earlier, I cried for the first time in a while. In fact, I cried all the way home, entirely unbothered by the stares I was getting from pedestrians who had to witness my meltdown on their way back from work. That’s what happens when the person I am for the day reconnects with one of the people I’ve been before, or worse, with several of them. I had another shoot the next day, and I prayed that I would still be, in spirit, an aspiring actress after the sun rose again.

Working with that TV show production was a blessing for my unpredictable sleep schedule. Not because it fixed it; quite the opposite, it encouraged its chaos. It served as an excuse to get no rest. Instead of feeling guilty for missing sleep, I had a reason for it. During that time of my life, I was playing a role: stunt double by night, psychology student thirsty for knowledge by day. It mostly consisted of night shoots, which would last all night in a new Hungarian city every day; all of these shoots were directly followed by my going to my morning classes and pretending as if nothing special had happened. On one of those nights, I voiced my wonder to my favorite assistant director in that crew. “This is insane!” I said, looking around me and then up at the illuminated ceiling, absorbing it all. “Imagine being on drugs and walking around here,” I said. “Oh, darling,” she said. “Everyone here already is.”

I broke away from my thoughts as I reached the park, where I lay down in the grass, by the water’s edge, appreciating the day’s mundanity. My thoughts drifted back to that phase of my life when I had not seen a single sunrise, despite being wide awake at the time. Every dawn, I’d be on a bus, making my way to the restaurant. I rarely, if ever, saw anyone on the street, and on most days, aside from the bus driver, the bus was empty. Despite the loneliness, there was so much to admire about the city, even in the dark.

While the sun was rising outside, I was busy taking down instructions from the Hungarian chefs where I worked. I had landed a job as a junior pastry chef in a Michelin-starred restaurant in Budapest, purely by accident and despite no prior experience.

Needless to say, I wasn’t right for the job. Not only was I a 19-year-old student from Egypt who hardly spoke any Hungarian, but more importantly, I did not belong in the kitchen. In fact, my presence in any kitchen is a safety hazard. I am an accident waiting to happen. My colleagues, on the other hand — middle-aged Hungarian men with volatile tempers, scandalous vocabulary, and a level of English equal to my Hungarian — were exactly where they should be. We still got along for the most part, and the language barrier did not seem to concern them nearly as much as it bothered me.

But I did learn a lot, both about the profession in general and Hungarian chefs in particular. I now know how to make a fancy chocolate mousse, how to decorate jelly, and how to discreetly treat self-induced burns. But I also know that Hungarian chefs never apologize. Not that they ever needed to, as I was apologetic enough for all of us combined. Every slip-up I made, and there were many, was followed by my saying Nagyon Bocsánat — a contrite “very sorry” that, to my chagrin, as I later learned from a less accommodating and English-speaking chef, was not even a proper Hungarian expression. To this day, I am unsure if he was serious or merely adding insult to injury.

In that kitchen, I was Nadia. I don’t quite recall how that came to be. I’m assuming that someone must have found my given name too cumbersome to pronounce or unimportant to get right, and everyone followed suit. Every time they’d yell “Nadia,” I would respond with “Nadine,” but it never made a difference. Ironically, the only day they called me by my name was the day I quit.

I knew from my first day on the job that I would not last. Aside from the burn injuries, the job’s clashing with my academic progress, the underpaid physical labor, and the unsolicited inappropriate comments I’d receive were all battles – not easily won, but fought nonetheless. However, my biggest challenge there proved to be boredom. It was a kitchen full of personalities, opinions, and ultimately lives that were not accessible to me. It was not a place that inspired curiosity or the intimacy of sharing life stories or even making chit-chat, which naturally meant it was not the place for me. In fact, the person most willing to engage in conversation with me was one whose English vocabulary was limited to a few pleasant phrases that boiled down to Problem! No problem! and music. I eventually decided to seek a friendlier space.

My back began to throb from lying on the ground for too long, so I changed positions to a more comfortable one. I opened the book I had brought with me, Esther’s Inheritance by Sándor Márai, fully understanding the irony of buying the Hungarian author’s work in English. The plan of being nothing for the day was coming to a failed end; as I got more invested in the book, I became someone again. Today, I’m Esther, a woman meeting an old lover in the 1940s after two decades of separation. I find in her some qualities that resonate with me, but I also take on the ones that don’t. Today, adopting Esther’s spirit, I will accept back into my life someone I know I shouldn’t, one who forgives an incorrigible lover. It’s okay, though, because by tomorrow, she’ll be gone, and I’ll have morphed into someone else.

Amazing writing Nadine!!!

Your writing is sweeter than the chocolate mousse you learned to make. Super proud of youu!!

Tus escritos siempre son inspiradores, espero que siempre difundas tus pensamientos por escrito. Te deseo éxito y felicidad en tu vida Nadiny.

That’s insane