Are we watching or being watched? Ali Cherri’s new show in Marseille, on view through the 4th of January 2026, deconstructs the museum from the inside out.

It’s a bit like that abyss quote; if you look at history long enough, history starts looking at you. We are hit by this realization when we walk into the exhibition Les Veilleurs (the watchers, the watchmen), by artist Ali Cherri, at the [mac], the Musée d’Art Contemporain of Marseille.

The show prompts viewers to reevaluate the museum and, through it, the way we perceive history, upending the Mayan concept of strict chronology. We begin to think about history less as a linear succession of events, war, and artistic movements — mostly under Western guidance — but rather as a history of encounters, of findings, of stories. Of something that starts in medias res.

This non-linear conception of history is what museums around the world are showcasing, from the main exhibit at Louvre Abu Dhabi to the National Gallery of Singapore and the National Gallery in Rome. We can’t sustain the illusion of linear time any longer, the illusion of order, the illusion of art history, the illusion of being those watching, and not being watched in return.

This is what Les Veilleurs is telling us from the very first room. The entry point is already a mise à l’abyme: a photograph taken in 2020 depicts the storage space of the Marseille History Museum, whose geometry replicates and multiplies the actual architecture of the mac’s room, a gateway of sorts. By presenting rows of drawers and archival shelves, Cherri makes a clear statement: what lies behind the façade is equally worthy of attention. We are prepared to step into an exhibition turning inwards, exposing its own architecture and logic.

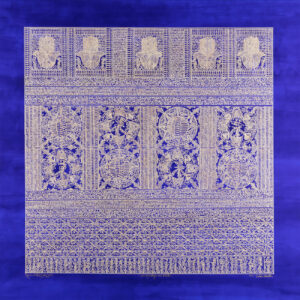

Behind the photograph, another surprise, another inversion: on an illuminated table are displayed a series of assemblages of heads and eyes, each turned toward the viewer. Among the objects are votive faces from antiquity, decorative fragments from 19th-century funerary monuments, Romanesque heads, and anthropomorphic busts with worn features. Their materials vary: stone, terracotta, plaster, and bronze. At first glance, it seems these faces are just displayed, but soon one realizes they are also positioned to look at the viewer. Every fragment looks back.

The vitrines divide and reflect them, creating a kaleidoscope of partial identities. Some have no eyes; others are nothing but eyes. There’s a tactile intimacy in their presentation; no didactic labels, no clear hierarchy. The visitor is forced to circle the table, lean in, and step back, and in this process, the viewer’s own body becomes part of the rhythm.

The lightbox where the artefacts are positioned removes all shadows, creating a ghostly suspension of matter. Objects float in space, decontextualized yet vividly present in their uniqueness. The transparent vitrines that separate them almost amplifies the imperfect, damaged form of the archaeological objects, arranging the fragments into loose constellations. Grouped by size and material, rather than by historical chronology, they appear to have a rhythm and tone, almost like a musical composition.

The birth of a show

Stéphanie Airaud, director of [mac] and curator of the show, explained that in 2024, when the museum acquired Ali Cherri’s work “The Gatekeepers FIRE and WATER,” a work originally created for Manifesta, she suggested Cherri come up with a specific presentation that would be in dialogue with the collections of Marseille’s museums.

To choose the works and objects that would be included, the artist and the curator identified several themes directly related to “The Gatekeepers” totems, such as animality, hybridization, the gaze, the face, sleep, and vulnerability.

The artist’s selection favored not masterpieces but misfits: damaged sculptures, minor artifacts, unremarkable busts, anonymous fragments. He picked up what is rarely seen, and arranged these works in ways that blur lines between conservation and apparition — à la Gustave Moreau.

“With Cherri, we selected the pieces through dialogue about their materiality, their presence, their trajectory, and the sensitive and formal correspondences that emerged between these pieces from the collections of the Marseille museums and Ali’s work,” explained Airaud. “The pieces gathered and displayed here are objects that have rarely or never been shown, are fragmentary, little recognized or known, but all bear witness to the material production of human civilizations, from ancient Egypt to contemporary Mexico.”

Scenographer Martin Michel and lighting designer François Austerlitz accurately translated Ali Cherri’s ideas, for whom the spatial arrangement is an integral part of the visitor’s experience.

The lack of labels stresses the importance of allowing the objects the freedom to be presented before the viewer and together without the apparatus of knowledge constituted by institutions. The only written voice in the exhibition is that of the author Karim Kattan, whose text commissioned for the exhibition can be found in the exhibition’s booklet, which contains notes on the works presented.

, Marseille’s Musée d’art contemporain (photo Grégoire Edouard, Ville de Marseille).,https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/Ali-Cherris-totemic-fish-watcher.jpg|Ali Cherri, “Les Veilleurs,” at the [mac], Marseille’s Musée d’art contemporain (photo Grégoire Edouard, Ville de Marseille).,https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/good3.jpg|Ali Cherri, “Les Veilleurs,” at the [mac], Marseille’s Musée d’art contemporain (photo Grégoire Edouard, Ville de Marseille).,https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/Ali-Cherri-good.jpg|Ali Cherri, “Les Veilleurs,” at the [mac], Marseille’s Musée d’art contemporain (photo Grégoire Edouard, Ville de Marseille).,https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/Installation-view-of-Ali-Cherris-Les-Veilleurs-at-the-ac-Marseille-1.jpg|Ali Cherri, “Les Veilleurs,” at the [mac], Marseille’s Musée d’art contemporain (photo Grégoire Edouard, Ville de Marseille).”]

The chimera

As visitors keep walking through the rooms of the [mac], they start questioning what they see, as throughout the show Cherri is mixing the real objects from the reservoir of the Marseille museums with sculptures, objects, videos and artworks of his own making, to the point that it is sometimes difficult to tell what is “original” and what is “artist-made.” And in a label-less show without a strict chronology, is there even a difference?

This blurred line between conservation and artwork brings to mind the practice of other artists, who created their own fictional sciences and institutions, from Waalid Raad and his fictional foundation called The Atlas Group, or Khalil Rabah who created The Palestinian Museum of Natural History, and also Singaporean Robert Zhao Renhui, who created The Institute of Critical Geologist, where he presented viewer with partly-real, partly-fictional science.

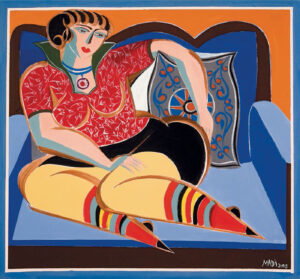

A strong image that represents this way of muddying the waters that artists adopt to question absolute truths is well-represented by the image of the chimera. It is this mythical figure — the one artwork in the [mac] show which was picked to promote the show on the billboard and on the side of buses all around Marseille — that encapsulated the meaning of this exhibition.

A body part-animal, part-human, topped with a small, archaic-looking head. The head appears disproportionately small, as though the creature is not carrying a brain, but rather some mythical dimension from the past. The sculpture is made of a mix of materials: clay, straw, and sand, resulting in something that seems archaic, scary, and invented at once.

The chimera is an interesting image also because it corresponds somehow to our way of interpreting history, or perhaps the artist’s way of doing so. There is the body of the chimera, which we can assimilate to the hard, data-based, source-based part of historical knowledge — and then there is the imaginary, our surimposition, and how we read history according to our sensitivity.

Peeling the layers

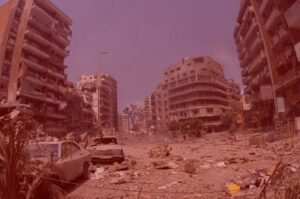

As one moves beyond the first gallery, the strategy of the mise en abyme deepens. A second photograph, displayed like a window, depicts the Salle de Paléontologie et d’Anatomie Comparée at the Musée Nationale d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris. This is not an image created specifically for Les Veilleurs, but it strongly resonates with the rest of the show.

It shows a room full of animal skeletons and taxidermized animals, vitrines full of bones, and in the center, a human anatomical model, an écorché, with its skin peeled back. The only living figure is the artist, who lies asleep on a bench, just at the feet of the model.

This photograph is titled “Still Life.” The reference to the pictorial genre is intentional and ironic: what is “life” in this tableau is precisely what is most artificial. The écorché becomes yet another symbol of a layer of reality which has been peeled off, but also a surrogate for the artist himself, which still inhabits his body, while being lost in his dreams.

Moving into the second gallery, the mood shifts again. A large wooden table, reminiscent of a taxidermist’s workbench, displays delicate watercolors of dead birds. These were painted by Cherri himself during the pandemic lockdown, and are based on specimens from his personal collection of taxidermized animals.

The drawings are meticulously arranged, each accompanied by small handwritten tags, imitating the labeling system of natural history archives. We are faced with yet another questioning of labels, descriptions, the attempt to categorize life itself. But more than scientific studies, these watercolors are akin to mourning and slightly morbid portraits. We are left thinking that the act of classification itself robs a creature of its vitality. And in this sense, does the creative act of drawing hold the power to eternalize life?

Around the table, vitrines display further sculptural works: again, a mixture of the artist’s own pieces and borrowed artifacts. In one, a bird perches beside a stone lion; in another, two taxidermized owls stare blankly across the room. The ambiguity between natural and artificial, between specimen and sculpture, reaches a crescendo here. There is the idea of an ecology of form, resistant of categorizations.

The theatre of shadows

The final gallery functions like a stage. Here the light is theatrical. Cherri installs one of his sculptures on a raised platform, together with a Mexican figurine, and behind it, a shadow screen casts elongated silhouettes. The play of real and projected forms recalls shadow puppetry or early cinema. In a way, we begin to study the shadows as though they were characters unto themselves. We watch the sculpture, but we are also watching its double.

Not far from these figurines, two video works are projected here, in dialogue. In one, we meet “The Digger,” a man who visits a necropolis in Sharjah, an actual archaeological site whose tombs have been emptied, their contents moved to a neighboring museum. The man, whom we only see from a distance, patrols the dry, abandoned ground, as the last witness to a dislocated past. The second video, projected opposite, is the interior of the Natural Museum of Sharjah, a luxuriant yet immaculate space, constituting a strong counterpoint to the desert location.

In the show are also some paintings that work by virtue of surprise or loose association. Among the more haunting paintings is definitely a cracked image of a nativity. The leitmotif of going beyond the surface comes back here: the painting is so consumed that the paint shows its support, the raw canvas, which shows through.

Conservation experts have halted the restoration of the canvas, which has been varnished not to recover but to stop further loss, and it exists now in a state of arrested decay. Cherri’s choice to include it is telling. Like the écorché, like the birds, like the sleeping watchman, this painting is an emblem of suspended time, and a memento mori of the impermanence of all things.

Finally, by walking through the show, we finally meet the gatekeepers, Les Veilleurs — the two totemic figures that the artist created initially for Manifesta — which constitute both the starting point of the show and its conclusion.

The feeling is that rather than an exit, these two figures constitute a portal to a new consciousness. What the artist seems to propose is not an alternative history, but a critique of how histories have been conceived up to today. He opens up the idea of what a museum can be.

As Cherri explains, “…as a filmmaker, I give the viewer a point of view that I determine with my camera, I dictate what I see: first a landscape, then a close-up of a face, followed by rain through the window, and so on. I try to think about the exhibition experience in much the same way.

“So I put myself in the visitor’s shoes to think about the scenography and lighting. Furthermore, as the works are shown without their academic and museological references, the landmarks are blurred, and the forms merge together.

“Perhaps this is how a universal imagination can be constructed in which everything is mixed together, where we feel that this or that object belongs to all of us,” concludes Cherri.

Ultimately, the Veilleurs invites us to keep vigil, to linger, to pay attention, to familiarize, and finally to approach reality beyond strict categories. In that, we are called as subjects, as makers of our histories and participants in the grand narrative. We are the ones putting the little head of our own making on the body of an ancient lion. Forever hybrid, but constantly in search of order.

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille.jpg)

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)