A new book traces the development of a relatively new art history in the UAE.

The Development of An Art History in the UAE: An Art Not Made To Be Understood, by Sophie Kazan Makhlouf

Anthem Press, 2024

ISBN 9781839992407

“If I had stayed in the UAE, I would have never become an artist.” —Abdul Qader Al-Rais

Jelena Sofronijevic

Within Emirati artist Al-Rais’ proclamation is an assumption that oneself — like one’s history — is often defined by the perception of others. Sophie Kazan Makhlouf’s new book, The Development of an Art History in the UAE: An Art Not Made to Be Understood is a combination of visual and oral histories, recounted through conversations, interviews, and first-hand testimonies. It charts the development of the United Arab Emirates’ art history from its own perspective.

While the art may not be made to be understood, Kazan Makhlouf’s story explicitly is. At just over 100 pages, of clearly defined chapters and maps, the book is directly pitched to help readers grasp the meaning and relevance of art from the UAE. Implicitly, those readers are other-than-Emiratis, evident too in the exclusive use of the English language, and conversion of dirhams into pounds and dollars. Moving back and forth between the individual and the national, the book works to personalize — perhaps humanize — the narratives of a country most outsiders encounter through singular and stereotypical representations of great wealth, oil and gas extraction, and human rights abuses.

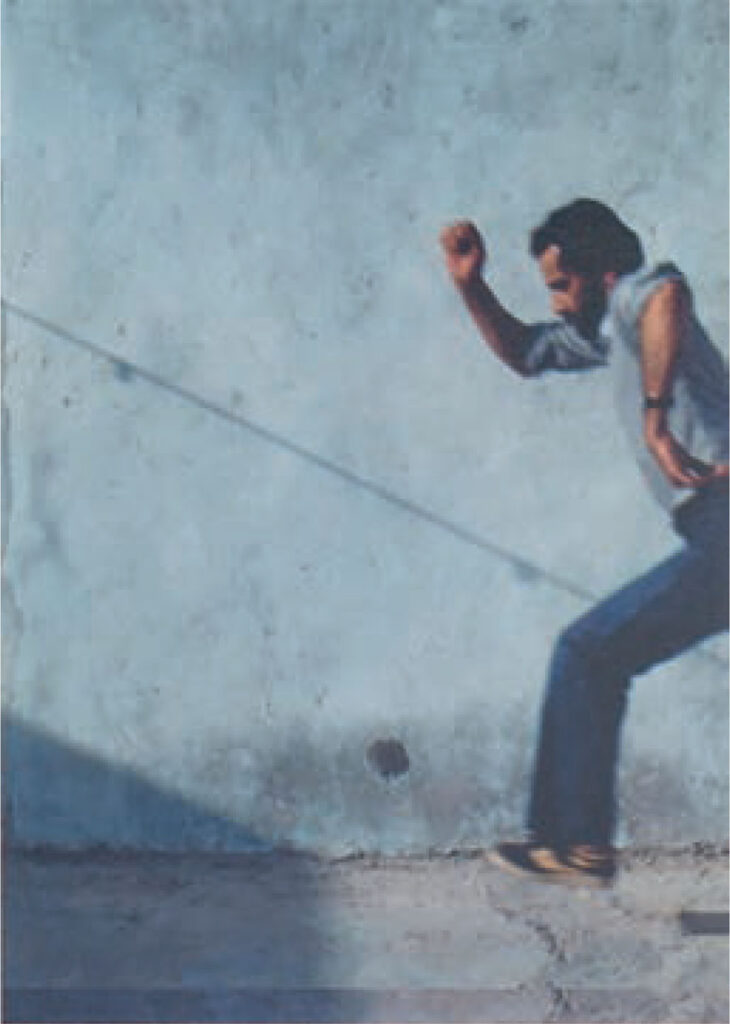

This is not to reduce Kazan Makhlouf’s project, or the work of artists from the region, to their political intent or importance, but to highlight the nuanced ways in which histories and socioeconomics have shaped artistic practices, publics, and markets. The book’s subtitle is taken from the words of Hassan Sharif, one of the best-known artists from the region, who obliquely suggested his work was intended to provoke a reaction, “an Emirati art audience into existence.” The urgency and movement in his photographic series Jumping (1983) reflects his pursuit of education across the UK, from Leamington Spa and London; his latter statement, his awareness of his privilege, and wish to return to the UAE to teach. The performative element of his practice diffused through his circles, and into the next generation of contemporary practitioners, including Mohammed Kazam and Ebtisam Abdulaziz, working with video, film, and sound, and installations.

Jumping embodies Sharif’s early interest in British constructivism and conceptual art, recalling perhaps Bruce McLean’s HEADLESS ARMLESS LEGLESS RUNNING ARTIST (1970), a series now in the British Council collection. While wanting to “clean … away” his first work in political cartoons on arrival in England, his agency and explicit critique may have come as a surprise to his contemporaries — as today. Kazan Makhlouf’s book challenges both blatant misconceptions, including that there was no art in the UAE prior to the creation of the state in 1981, and more pervasive ones, above all, that the authoritarian nature of the government might preclude the possibility of politically critical cultural production altogether.

Visually, critique comes in more subtle forms than Sharif’s “caricatures,” here diplomatically interpreted and related by Kazan Makhlouf. Al-Rais’ “Decay” (1980) is read as a delicate depiction of social deconstruction, making way for what expert on culture and heritage Sulayman Khalaf calls the “wealth of high-consumption, air-conditioned life.” This slow painting and still moment in time stand in ironic contrast with the rapid deconstruction and reconstruction of major cities, like Sharjah, Abu Dhabi, and Dubai.

Al Rais’ triptych “Bishra” (Announcement) (2007-2008) was the first work by an artist from the Gulf to be sold at auction in the latter, largest city, the only one in a sale held by the London auction house Christie’s in 2008. The fall of the hammer, at an unprecedented one million UAE dirhams or £213,000, was heard by local and regional art markets and more widely. Since then, Christie’s Middle East has dramatically expanded, with specialists based between Dubai and London and, from 2023, an annual loan exhibition not for selling (directly), but rather public representation, education, and free access.

In the book, the mistaken date (2006) of that first auction and confusion of the names, Sulayman with Suleiman, reflect the book’s position as work-in-progress, a writing of history as it happens. In Western/European terms, the UAE’s art history seems short, its institutions young, with the first art colleges established in the early 2000s. Such observations are often made by practitioners across the WANA region, including Sara Shamma, a Damascus-based painter who recently shared their experiences of “rebelling against” a conventional arts education in Syria on the EMPIRE LINES podcast.

Contemporary art exhibitions have served as important sources, and catalysts for research, in Emirati art history. In 2009, the UAE was the first Persian Gulf state to present a national pavilion at the 53rd Art Biennale in Venice; Kazan Makhlouf cites it, and the catalogue, frequently. In this context, and short text, minor factual errors can have a disproportionate impact on archives and research, especially those returning to this text in the future.

“The extent of art produced in the UAE… is remarkable,” she writes, interested in the reasons for “this exciting artistic renaissance and the rapid development of the UAE’s contemporary art tradition.” In structure, Kazan Makhlouf moves back-and-forth between biographical (and economic) and artistic descriptions of the works, reflecting how the attribution of value is slippery, and never simple.

The Development of An Art History in the UAE also uses art to expose and challenge deeper stereotypes. In her Autobiography series (2012), Ebtisam Abdulaziz addresses how modernity and modesty are not mutually exclusive, by exposing the most private things about herself — her bank details. Perhaps, though, this performance only reinforces the role of cash, money, and conservatism in society. Indeed, Abdulaziz first pursued an education in mathematics, like the former accountant Karim Shomely, and many other women for whom the study of art was not available. (Kazan Makhlouf remedies this, in her implicit inclusion of a number of younger women.)

The author also speaks of the interplay between historic and contemporary practices that are most particular to this context. Mohammed Mandi is the most renowned calligrapher of the UAE, a master of the “traditional,” sacred form, who has also designed the lettering and visual motifs for government ministry logos, and the current banknotes for the UAE’s Central Bank. Mandi’s dirhams remind us of these two-way flows, how the conditions for cultural production are shaped by the state, and the role of artists in state and nation building.

Emiratis comprise around 11.5% of the population of the UAE; the vast majority are expatriates, particularly from India and Pakistan. The Development of An Art History in the UAE is Emirati-centric. It also attempts to somewhat liberate artists from their nationality, referring to artists who are Emirati, rather than Emirati artists, for example.

Kazan Makhlouf does not attempt to situate Emirati art within global or Western/European art histories, but rather suggest the relevance of their discourses in the context of the UAE. While acknowledging the countless migrations made by artistic and works in travel, education, and exhibitions, the book is modest, suggesting how these artists contributed to these other contexts, or to global art historical discourses.

The two-way flows, though, are evident in their practices. Following her first degree at Sharjah in 2010, Shaikha Al Mazrou obtained funding from the Abu Dhabi Music & Arts Foundation (ADMAF) to study a Masters’ in Fine Art (MFA) at Chelsea College of Fine Art in London, where she began to explore materials in sculpture. Though the artist returned to Abu Dhabi, her “Red Stack” (2022) has remained, exhibited at Frieze Sculpture in London in 2022, and permanently relocated to Tremenheere Sculpture Gardens, in a remote part of Cornwall.

Connections to the UK beyond London are only referenced; more in the South West can be found in the book’s acknowledgements to UAE artists Afra Al Dhaheri, Asma Belhamar, and Gaith Abdulla, otherwise known as the “Porthmeor Studio team.”

Exploring these networks would enable more critical, transnational and transcontinental analysis. Al Mazrou’s “Circuit Boards” (2011) — like Elias Sime’s intricate, woven sculptures — make use of electronic waste, discarded and found in markets. Their shared materials, and different practices in the UAE and Ethiopia respectively, speak to their different relationships with technology and time. Where Sime’s work relates consumption in Western/Europe with dumping across Africa, Al Mazrou, in Kazan Makhlouf’s reading, is more focused on their own nation and culture, its “constant desire to be at the forefront of change, to develop and advance in digital and technological markets, which become so quickly outdated.”

Much is made of the tendency towards “modern” media, including film, moving image, and video art, especially by emerging artists. Later installations by contemporary “masters” like Hassan Sharif utilize plastic objects like combs, developing the criticism of consumer culture first noted in the 20th century. Perhaps these forms are also more accessible, and visually relevant, to the lived experiences of younger publics, than more conventional art forms and histories.

At the same time, Kazan Makhlouf’s study resists the double marginalization of outsider perspectives, neither imposing external values or approaches to development, nor the expectation to learn lessons and “do better.”

“There are no right, only different, ways,” the author suggests — perhaps a subtle rebuke of some others’ hypocrisy in criticizing the country more widely. Nor has the lack of conventional arts institutions meant a lack of education, for the privileged few. Private money — and a plurality of grants, scholarships, and fellowships — has ensured artists and works have flowed across the world.

The book suggests UAE’s unique order of art historical development; of artists first, then the institutions to teach, collect, and market them. The captions credit names and organizations now familiar, even ubiquitous: Barjeel and Sharjah Art Foundations, Louvre Abu Dhabi, and Lawrie Shabibi Gallery, only reinforcing these institutions’ remarkably rapid rise to global prominence. As fascinating stories are the non-conventional arts spaces encountered along the way, including the Al Ahli Sports Club in Dubai, where Sharif staged an exhibition on his return from England in the 1980s.

These complexities of privilege and responsibility are the most interesting elements of The Development of an Art History in the UAE. The work of younger and contemporary practitioners reflects these tensions, between critiquing and calling for the realization of rapid change. Afra Al Dhaheri’s sculpture “Preserving Impatience” (2017), and Nasir Nasarallah’s “Story Converter” (2012) and “The Stories Vending Machine” (2013–2018), consider how such change has become everyday, overlooked, as well as the commodification of historical memory.

Kazan Makhlouf highlights how, more recently, the internet and social media have played an important role in providing accessibility to cultural events, enabling people to personally and directly engage with artists, museums and galleries. Sarah Almehairi’s Artist Talks, a YouTube series with early and mid-career practitioners like Al Mazrou and Amba Sayal-Bennett, is referenced, an example of how artists are using global platforms to amplify each others’ voices directly. (Absent, though is Kazan Makhlouf’s own series, Art Minute.)

Almehairi’s Talks were a product of the Covid pandemic, to which a whole chapter is devoted. This compressed history, perhaps unintentionally, ensures the impacts of the lockdowns are covered to scale, experiences again relevant to newer readers. Touching on the global project Seeing the Invisible, whose participants included Mohammed Kazem and Ai Weiwei, the book begins wider, transnational conversations, especially about the position of the “Middle East” in relation to the Global South.

The writing of contemporary history should create space for more interpretative analysis and speculative art historical exchanges, some of which might exclude Western/Europe altogether. In the section on traditional crafts, photographs of Talie decorative piping laid atop an abaya, or women’s robe (abaya) recall kumihimo, a process of Japanese silk braiding that also defies binary understandings of art and craft.

In her own conversation with the Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington, Kazan Makhlouf calls in to America from London, appearing in front of an ornate, wooden, mashrabiya screen. Online, she is vocal about the opportunities for fresh values in this new context, as the UAE hasn’t inherited the same hierarchies as Western/European art histories. More could be said of these “old-world” in the book, were their focus to relate cultural production to other contexts; as noted, Kazan Makhlouf is more concerned with questions relevant to the context of UAE, including whether textiles, like calligraphy, constitute kinds of art forms.

Though artists from the Emirates pursued a conventional, institutional education in Islamic arts in the UK — at more familiar institutions — Kazan Makhlouf says that it was in the UAE that they alighted on the art all around them. Sharif too suggested that his art required the viewer to walk — or perhaps, jump? — into new spaces. However, the idea of venturing into new territories, interpretive and cultural change is less common to Western/European publics, than those in newer, more rapidly-changing countries like the UAE. The Development of an Art History in the UAE is thus not only an effort to broaden art historical discourses, but a call to its readers to take responsibility, to get out, and widen their own perceptions.

Though temptingly concise, this text should only be read as a primer, a starter for further, independent research.