Select Other Languages French.

Architects mimicking Nature must first divest their practices of unsustainable materials and energy inefficiency. As planet temperatures rise, architects in the Middle East eschew western fixes and revitalize local solutions. The Bahrain pavilion and a traditional wind-cooling system won the biennale’s Golden Lion Award for Best National Participation.

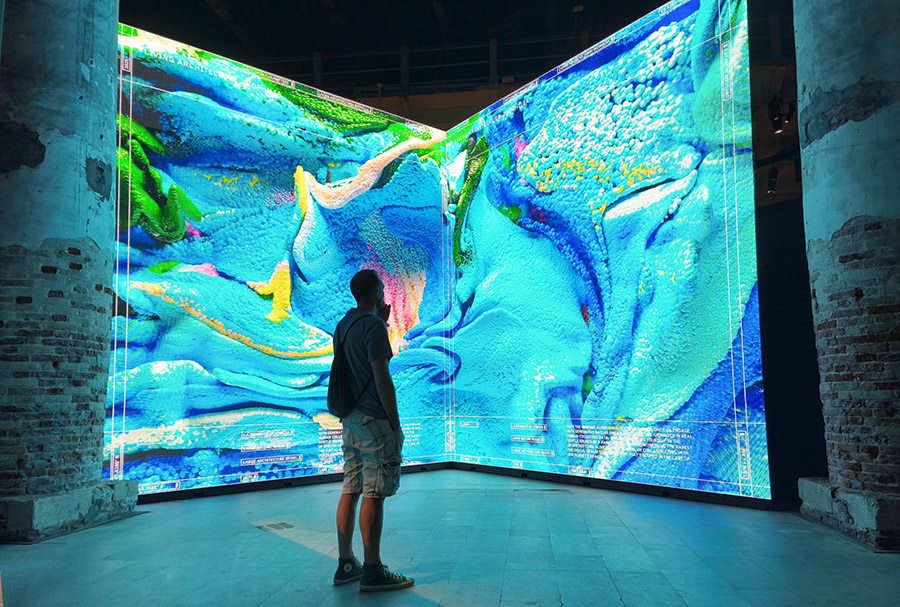

Visitors to this year’s Venice architectural biennale must pass through a stifling, dark room hung with a/c external ventilation units, choked in smoggy heat and stagnant pools of water to access the main exhibit. This sweaty, oppressive preview is the biennale organizers’ vision of what a hotter, unequal future will feel like to those on the wrong side of energy poverty who, unable to afford artificial cooling, are condemned to the searing outdoors heat.

Dunking the biennale’s typically privileged visitors into the waste heat emitted by the organization’s cooling needs is a Venetian version of waterboarding. It evokes the sacrifice zone produced by our fossil fuel era while making for a powerful introduction into an unusually packed 45th edition.

Suffocated by the stagnant narthex, the visitor pushes through a black curtain to emerge into a deliciously cool, white exhibition hall. Reveling in the taut relief, a glance back at the separating wall reveals two air conditioning trees (twelve a/c units stacked in two rows) pumping out a reprieve from rising temperatures. Though initially received as a godsend, the implication is that rather than a/c solving the problem it seeks to address, it only compounds it.

The introductory text reminds us that the biennale’s brutal welcome is a spatial allegory for our thermal future’s glaring, daily-expanding global inequities. Rather than viewing architecture as an act of purely material addition, the biennale explores the processes of entropy and a future of partnering with Nature rather than dominating it. Instead of greenery being treated as decorative, or uprooting it to make space for further profit-making buildings, it can be adapted into biological infrastructure that cools cities, purifies their air and restores a semblance of balance.

The biennale’s echoing main hall is crammed with exhibits demonstrating how biomimicry — the idea that architects can emulate nature — can reduce construction’s high energy imprints, insulate buildings and recreate the charitable, population-sustaining effects of wetlands. However, just as biomimicry has been criticized as being little more than a superficial way of emulating Nature that fails to reduce unsustainable materials or energy-intensive processes, the biennale dangles the prospect of a plethora of solutions without ever addressing the elephant in the room: Without a massive change in how global elites continue conducting their energy-intensive lifestyles and militarized squabbles, we are all merely sleepwalking towards doom.

Middle Eastern heat-solving shortcuts?

No other region deals with a combination of looming climate change and elite insouciance more than the Arabian Peninsula. Faced with some of earth’s most extreme temperatures, water scarcity, and a near-absolute dependency on importing essentials, its leaders have buckled down over the past two decades on geopolitical competition and colossally wasteful prestige projects, instead of actually addressing their societies’ structural and existential threats. Saudi Arabia has been spending its declining oil revenue in constructing a futuristic city in The Line and, along with the UAE and Qatar, dedicated billions of dollars to invading and destabilizing poorer countries like Yemen, Libya, Syria, and Sudan. This valuable treasure and time could have been dedicated to adapting their economies away from a near-exclusive dependency on exporting fossil fuels to deal with the double whammy of a climactically more extreme, post-oil tomorrow.

It was a surprise then that the small island-nation of Bahrain, a success story in terms of bypassing oil extraction to develop regional banking services, won the biennale’s prestigious Golden Lion award. In 2010, it became the first Gulf nation to appear in the Venice Biennale, surprising at the time by garnering a Best National Participation award for its Reclaim-themed pavilion. Coping with climate change proved an evergreen subject, and the curator of its Heatwave-themed 2025 pavilion, Venice-trained Italian architect Andrea Faraguna, designed an outdoor cooling system inspired by traditional wind-cooling techniques once current on both sides of the Persian Gulf.

“We already have in our heritage fabulous and very strong examples we can build on,” said Egyptian architect Omniya Abdel Barr, who admits that a corpus of indigenous knowledge was lost in the half-century between the generation of architects of the 1940s and 1990s. “But because most of the educational system is based on western methodologies, even when we set ourselves the task of solving heat-related problems for which we have a vast reserve of techniques, we still approach them from a western rather than a local and grass-rooted traditional approach.”

Although Bahrain’s representation by an Italian architect raised eyebrows, Faraguna’s project proposed cooling outdoor areas through plunging pipes to a 20-meter ground depth, then using a network of nozzles concealed within a metal canopy to funnel hot, room-temperature air through the cooler ground back into the outdoor space. The pavilion adapted to a biennale ban on digging by capturing cooler air from the conveniently situated water canal passing outside the warehouse.

“It’s simply physics,” said Dana Ahmed, one of two Bahraini pavilion moderators. “Dense cool air tends to go down while lighter hot air goes up, so it’s an all-natural dynamic, and the only electricity we’re using is to absorb the air; the most electricity-intensive part of air conditioning, which is the cooling, happens naturally as it cycles through the ground.”

Once the biennale is over, the cooling technique will offer respite from the heat as a space to take a break under in one of Venice’s squares and in Bahraini construction sites where construction workers labor in the punishing heat and humidity.

Without a massive change in how global elites continue conducting their energy-intensive lifestyles and militarized squabbles, we are all merely sleepwalking towards doom.

Food security and ecocide

June’s Israel–Iran war drove a realization that greater self-sufficiency is necessary by underlining the fragility of Gulf states to disruptions in their consumer-goods supplies. Food security was at the heart of the Emirati pavilion, where architect Azza Aboualam demonstrated how greenhouses can be adapted to facilitate urban farming in a desert climate, by responding to local shading and water-retention needs.

Perhaps prompted by the realization that the difference between normality and chaos are just a few days of food disruptions (or a rocketed water desalination facility) away, the Emiratis have begun cultivating a range of essential and popular foods, including wheat, poultry, citrus, and coffee. So have the Saudis, as the large crop circles dotting the Arabian Peninsula’s deserts attest. Gulf sovereign funds have made large investments in East Africa’s agricultural land, exposing themselves to criticism that they are purchasing arable land that could be used to feed poverty-stricken locals.

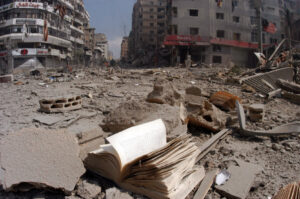

Conflict was at the heart of the Lebanese contribution, which was prepared even as Israel bombed and invaded Lebanon last year. An off-putting Israeli drone soundtrack accompanies visitors to The Land Remembers exhibit, “Many of whom had no idea we’d had a war recently,” co-curator Έdouard Souhaid noted, examining the ongoing and systematic Israeli degradation of South Lebanon’s fields and olive groves through a practice known as ecocide. Perhaps the most viral example of the systematic destruction of Southern Lebanon’s agricultural lands was a video of Israeli troops standing on the border with their neighbor, catapulting over fireballs. Taking the images of incendiary, bomb-saturated and phosphorus-streaked areas that featured in the Lebanese pavilion was one of Osama Farhat’s last actions; the civil defense member was assassinated by an Israeli drone strike in May this year.

“What the Israelis appear to have concluded is that a concrete arch can be rebuilt, but communities are destroyed when agriculture is struck,” said Souhaid, who is currently involved in a project recycling construction debris produced from Israeli bombardments. “That is what’s behind their relentless bombardment of us in the South.”

A timid, greenwashing biennale

Lebanon’s overtly political pavilion was an exception in an overall timid biennale criticized for curator and MIT professor Carlo Ratti’s “tech bro fever dream” approach. While climate change continues to threaten extinction, its priority has been downgraded since the world descended into global conflict in 2022. But this new turn of events is barely reflected in the biennale where, the contributions of Lebanon and the Silver Lion-awarded Calculating Empires: a Genealogy of Technology and Power Since 1500 aside, there was nary a mention among nearly 800 contributors of the effects of the ongoing global conflict on our already ailing environment.

“We were afraid of being cancelled (by the biennale) and ended up receiving criticism for not mentioning Israel by name in our curatorial statement,” Souhaid said of the timidity with which they approached their controversial subject matter. Israel’s pavilion was closed “for repairs.”

Despite repeated attempts by The Markaz Review to secure an interview with a representative of the biennale, the only option it was offered were written replies to questions submitted over email.

Venice is an apt setting for the biennale. Once one of the world’s most powerful city-states, this extraordinary maritime-urban confection transformed itself into an early tourism destination once it saw its hard power ebbing away after the circumnavigation of Africa opened new trade routes to the East. From the 17th century onwards, Venice leveraged its carnival to transform itself into the most entertaining station for British aristocrats engaged on what was supposed to be a horizon-expanding travel year known as the Grand Tour. Venice established the biennale institution in 1895 as a way of filling hotel rooms, maintaining the city’s allure, and attracting wealthier and more discerning demographics.

“The beginnings of a tourism economy were in the Middle Ages as pilgrims came here to embark on galeani (a form of medieval passenger and commercial ship) to the Holy Land,” said Margherita Carlon Minoia, an activist and masters student who protested the high-profile June wedding of Amazon founder Jeff Bezos in the city. “By the time of the Grand Tour, Venice was a very decadent place, with theatre and brothels being a big part of its tourism industry.”

Today, social media and GPS have accelerated Venice’s gentrification and touristification, even as climate change has prompted more extreme high tides (acqua alta) that submerge the city’s squares and lanes and bring the gondolas sailing over flooded land. Only one in four Venetian residents remain on the main island compared to its 1950s population of 175,000. Instead, tens of thousands of Italian and migrant workers commute from the mainland daily to work shifts in the pedestrianized town’s tourist-choked cafes, restaurants, shops, and hotels.

“The biennale’s high venue rental rates have an inflating effect on the city’s real estate,” said Margherita. “Hype and the rolling biennale seasons create a constant elite market for these spaces’ rental; the ‘stranger’ or ‘more exotic,’ the better!”

The boats headed out of Venice around shift-changing time are crowded with laborers and serving staff, crammed together at the end of their workdays. As they file off the boat at Piazzale Roma to disappear amid the cars on their way to their next mode of transport home, their lower social status compared to the tourists they have been serving is visible not just from their faces’ drawn lines and premature ageing, but also their eyes: more jaded and pragmatic than the staring, bright-eyed wonderment of their sleek tourist clients.

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)