How to Kill a Cloud, a documentary directed by Tuija Halttunen

Wacky Tie Films 2021, 80 mins

VOD Netflix

Farah Abdessamad

The United Arab Emirates (UAE) gave Finnish scientist Hannele Korhonen three years and $1.5 million to bring rain over the desert. In How to Kill a Cloud, filmmaker Tuija Halttunen chronologically follows Korhonen’s scientific undertaking, interrogating the supposed neutrality of innovation, human hubris, and the intersection of the climate emergency with nationalism — in a “story of chaos and dust.”

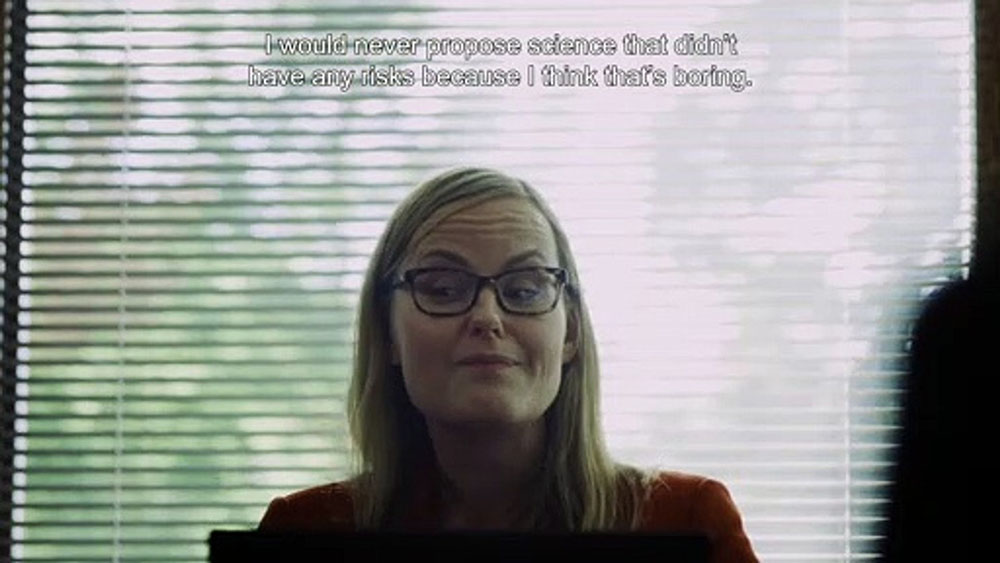

Korhonen is research professor and director of the Climate Research Program at the Finnish Meteorological Institute.

“Here’s a question, what if you could control the chaos,” the film narrator asks in a tempting-yet-foreboding tone, engaging with the primordial bipolarity of chaos and cosmos. Is one supposed to ever win over the other, or are these two world concepts destined to compete against each other equally and perhaps create something new, one is left to wonder. “The randomness of chaos is true equality,” the voiceover continues later, urging the viewer to pause on fundamental and multilayered issues of fairness, predetermination, and redemption.

Faith and doubt permeate the film. Korhonen — a scientific underdog compared with the more established researchers in the field — and her team win a call for proposals to participate in the UAE’s Rain Enhancement Program, a prude dystopian-inspired title masking a ghastly reality. According to the World Bank, the water table of the UAE has been declining to around one meter yearly, for the past 30 years. The UAE further is expected to deplete its natural freshwater resources in the next two generations.

What Korhonen and her team (which includes other creative titles, such as a “Cloud Appreciator” among its ranks) are developing are a cloud-seeding mechanism and an Artificial-Intelligence powered emulator, a code to identify clouds most likely to generate rain. In short, they scan the desert sky of the UAE to find rain-carrying clouds — nimbostratus and cumulonimbus. After “reading the sky,” as many indigenous and ancient peoples would have naturally done without such expensive equipment, they would recommend the spraying of aerosols (fine particles of silver iodide and dry ice) to change precipitation, effectively augmenting their chances to rain in larger amounts since most rain evaporates before it reaches ground level. In other words: climate-engineering, already in motion in the US and Australia.

Described as “an international research initiative designed to stimulate and promote scientific advancement and the development of new technology,” the Rain Enhancement Program is situated under the official patronage of UAE officials. It’s apparent during one of the early scenes when Korhonen participates in a project presentation in Vienna, chaired by H.E. Hamad al Kaabi, Ambassador of the UAE to Austria, and during the careful scenography of her following visits to Abu Dhabi at various stages of the project. During those visits, we see Korhonen and other scientists recycling UAE talking points in their various press encounters, stressing words such as “innovation” and “water security” to articulate the objectives to which they would contribute, to help amplify the UAE’s branding efforts.

How to Kill a Cloud brings up questions that aren’t anodyne — from the role of scientists as proxy demiurges deployed by an authoritarian state and regional military power, to the uncertain ownership of clouds (national, global good?), and the looming threat of climate-related terrorism, which could unleash floods or droughts upon dedicated targets.

The film rightly acknowledges the blurry ethics of the rainmaking project, even going as far at suggesting a kind of profanity towards nature, to what can be considered sacred. We identify a glaring contradiction between the quest pursued by the scientists harvesting pseudo-holy water to feed arid lands, the cultural-religious references of water in paradise recalled in the Koran, and a late-stage capitalist waste and overexploitation, for instance in the lavish pools of the luxury hotels at which they stay and the ridiculously small plastic water bottle from which Korhonen quenches her thirst. Water becomes a tacky, expandable décor — an obscene display of incoherence that overlooks everyday responsibility.

To whom do clouds belong, and what changes when weather and seasons shift? At first, cloud-seeding may seem like an assurance of finally reversing climate change, the one-and-all solution to bring down climbing temperatures in many parts of the world. The very tangible impacts of this worsening phenomenon are, of course, known — from the recent disappearance of Lake Sawa in Iraq, to the Gobi Desert sand and dust storms in Beijing, heatwaves in South Asia, and brave but necessary efforts such as the “Green Great Wall” of the Sahara Desert, which hopes to plant thousands of kilometers of trees to halt the expansion of sand dunes and desertification.

Korhonen justifies her lack of moral dilemma in the following terms: humans are already modifying the atmosphere through accelerated carbon emissions, so what? She isn’t doing anything more than what non-scientists are doing on their own, then. But what this means is that we recklessly absolve our agency away from irreversibly killing the planet. “I can sleep at night,” she says, disconcertingly. In the spectral presence of a red umbrella, dancing under the blows of the wind — it appears in Finland, and in later scenes in the UAE — we want to project an unexpungable presence, an alert, a lingering consciousness.

How to Kill a Cloud brings up questions that aren’t anodyne — from the role of scientists as proxy demiurges deployed by an authoritarian state and regional military power, to the uncertain ownership of clouds (national, global good?), and the looming threat of climate-related terrorism, which could unleash floods or droughts upon dedicated targets. The latter isn’t far-fetched given that the US military approached this technology’s possible application, such as Operation Sober Popeye during the Vietnam War in the 1960s, to prolong monsoons and control enemy advances in adverse terrain, and perhaps also operated by India. The thought of abuse is initially what drew me to watch the film, immediately seized by its terrifying potential given how water and its scarcity could become even more weaponized in our near future.

When a journalist asked about the likelihood of misuse during a press conference in the film, one of the UAE officials merely responds that there are regulations — quite as if we all lived in a perfect law-abiding world (and whose laws anyway, defending which interests?). The UAE has yet to ratify the 1978 Convention on the Prohibition of Military or Any Other Hostile Use of Environmental Modification Techniques.

How to Kill a Cloud also brings lighter, cringe-worthy moments in Korhonen’s arrival to the UAE to defend and promote the project. She’s a young white woman, conscious that the role her native Finland allows her to occupy vastly differs from the traditional place of women in Arab societies. This is quickly counter-balanced by a smart PR move: the presence of Alya al Mazroui on the Rain Enhancement Program team.

Crypto-Orientalist leanings do poke through when the camera repeatedly pans on a mural of hijab-wearing women. Korhonen mentions the sharia law, with undertones of a “us” and “them.” We hear recitations of the Koran; we see thawb-wearing men pouring coffee. The Golden Age of Islam and its scientific achievements is recalled before swiftly shifting to cocktail-drinking scenes of her socializing with various other (male) scientists. By showing Korhonen enjoying alcoholic drinks alone with men in a fancy hotel bar, we touch upon an uncomfortable truth: white privilege. Could someone like Alya be in this position? Probably not.

Halttunen wants to show Korhonen as a professional scientist, but also as a woman in tech, navigating heavily gendered-coded norms and expectations. In some ways, we do feel empathy for the scientist who was the first of her family to attend university. Yet this attempt at humanizing her subject feels forced and shallow, as it tends to minimize power dynamics (a white scientist expected to “save” the UAE, with the full suite of government-enabled exposure and respect) and trivialize her womanhood, such as when we watch her carefully plucking her eyebrows in an expensive hotel room. While appearances matter in a job that involves not only lifting technological advance but also (if not, equally) partaking to official representation functions, such cosmetic detail doesn’t add much to the story since the protagonist quickly becomes an insider, rather than someone who struggles with an ambiguous performance.

Halttunen wants to show Korhonen as a professional scientist, but also as a woman in tech, navigating heavily gendered-coded norms and expectations. In some ways, we do feel empathy for the scientist who was the first of her family to attend university. Yet this attempt at humanizing her subject feels forced and shallow, as it tends to minimize power dynamics (a white scientist expected to “save” the UAE, with the full suite of government-enabled exposure and respect) and trivialize her womanhood, such as when we watch her carefully plucking her eyebrows in an expensive hotel room. While appearances matter in a job that involves not only lifting technological advance but also (if not, equally) partaking to official representation functions, such cosmetic detail doesn’t add much to the story since the protagonist quickly becomes an insider, rather than someone who struggles with an ambiguous performance.

Benjamín Labatut’s book When We Cease to Understand the World (2021) masterfully shows how scientific advances and discovery can be intimately intertwined with madness, personal destruction and politically-instrumentalized havoc. It’s vital to revisit history to debunk positivist claims that all science is, by essence, good, and all future bears the promise of progress for humankind.

“The society needs to have moral decision on where scientific decisions will be applied,” Korhonen says, perhaps projecting her naïve if not delusional hopes for all regimes to be inclusive, democratic, and accountable to their population and their aspirations. If so, the world would indeed look quite different.

How to Kill a Cloud is featured on Vice’s The Short List. The film won a Premio Zonta Club award at the Locarno International Film Festival (2021), Best Film Testimony 2021 in the Jihlava International Documentary Film Festival, and Best Directing at the International Science Film Festival World of Knowledge (2021).

From chaos and dust, I found How to Kill a Cloud a story of opulent gold, and much dizziness. It draws you into a world many will immediately hate (power, prestige) with actors who hold very little accountability over issues that could affect the entire planet.

Watch this vertiginous documentary to engage with what it unveils and all that it leaves unanswered.